Europe is now on the verge of a contest that promises, from present appearances, to be the most bloody and destructive the world has ever seen. France on the one side, and Prussia, backed by the German Confederation, on the other, are so nearly matched in population, resources and military skill, that it would be a miracle were either of them to triumph, except after a fierce struggle and at the cost of tremendous sacrifices. The neutrality of Belgium, Holland, and Switzerland may be depended upon, though the violation of Belgian territory by either France or Prussia would undoubtedly draw Great Britain into the war.

The attitude of Italy is uncertain, though wise statesmanship would counsel strict neutrality on its part, not only because of the obligation it is under to both the contestants, but because it may have to deal with the revolution at home. It is reported that Austria will join France; and if so, Russia, unless intending to make a descent upon Turkey, will very probably side with Prussia. If, however, the other European powers stand aloof, both Russia and England are likely to remain neutral.

The immediate occasion of this terrible war was the offering of the vacant Spanish throne to Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern. The negotiation for placing this German Prince upon the throne of Spain was managed so secretly between Prim on the one hand and Bismarck on the other, that the world was unaware of it until the preliminaries had been arranged. France protested energetically against the contemplated step, and appealed to the King of Prussia, as head of the house of Hohenzollern, to prevent it. The King at first declined to interfere, refusing to assume any responsibility in the matter; but as affairs were rapidly assuming a grave aspect, Prince Leopold, on the advice of his father, formally withdrew from the candidature.

So far all the great powers were with France and against Prussia, but unfortunately, the matter did not end here. France demanded of Prussia a formal renunciation of all pretension on the part of any German Prince to the Spanish Crown, and this Prussia somewhat indignantly refused; and when the French Ambassador desired an interview with his Prussian Majesty at Ems, the latter positively declined to see him. Further than this, Prussia courteously informed the different powers, except France, that the French Minister had been dismissed. This step, according to the French Premier Ollivier, forced France to abandon negotiation and prepare for war.

So much for the immediate occasion of the quarrel. Its real object on the part of France is the "rectification of the Rhenish frontier;" on the part of Prussia it is equally certain that it has a strong desire to humble France and extend its own territorial sway. In a few days afterwards Leopold announced his candidacy for the Spanish Crown was announced, and though on the 14th or 15th he withdrew; yet on the 18th the declaration of war was on its way from Paris to Berlin!

Will the same celerity characterize the war?

That will depend in great part upon whether it can be confined to the principals. If it could, and they both come out of it, as they undoubtedly would, thoroughly exhausted, no matter who got the victory, Europe would have some guarantee for a long term of future peace. The designs of Russia are solely directed towards the East, and Russia excepted, Prussia and France are the two powers whose ambitious designs and schemes for their own aggrandizement continually menace the peace of Europe, and impose upon the nations immense burdens of taxation for military purposes.

It is desirable that they both should be strong powers, but it would be a misfortune were either of them to gain a very great preponderance over the other. In that case, other nations would undoubtedly be dragged in, and the war begun between France and Prussia would widen out to the dimensions of a European war. The bitter feeling manifested in England against France, and the general opinion so freely expressed that there was no just ground of a proclamation of war point to certain unpleasant possibilities. The maintenance of neutrality by Great Britain will be difficult in any case; but should Prussia waver, is it likely that Britain will stand by and see her defeated, believing that the quarrel was unfairly thrust upon her? When Prussia and Austria plundered Denmark of the Duchies, France and England protested against the robbery and allowed it to proceed. They acted on the belief that it was better Denmark should suffer some injustice than the whole of Europe should be plunged into war. They will both suffer now for that mistake. Prussia carried off the whole of the spoil, and the consequence was the Austro-Prussian war.

Now we have as a consequence of Prussia's extraordinary success in that war, another war springing from the Prussian ambition being stoked, and the French jealousy it created. Austria became wise after her defeat. Prussia consolidated her strength and prepared for fresh conquests, and Napoleon, seeing the mistake of allowing Prussia to become so great, was impatient for a pretext to strike her. Had England and France stood dutifully by Denmark when attacked by the two great German powers, France would not have had occasion to measure swords with Prussia, nor England to look forward to the serious entanglements with which she is now threatened.

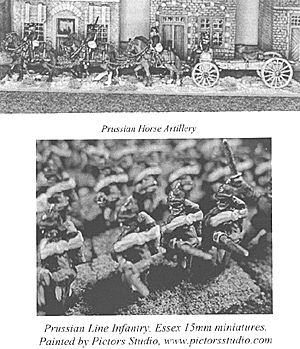

This article is the prelude to a Franco-Prussian War campaign that my local group will be participating in starting next month. I hope to include a series of updates and battle reports in the next few issues of this newsletter.

Back to Table of Contents The Messenger August 2003

Back to The Messenger List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by HMGS/PSW.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles covering military history and related topics are available at http://www.magweb.com