A Century of American Forbearance

During our Revolutionary war, Spain, France and the United States were allies, and the treaty of peace signed in 1783 was between England on the one side and the allies on the other. Hardly was the ink on the treaty dry before Spain made extravagant claims concerning the boundaries of Florida, and even denied our right to territory between the Allegheny mountains and the Mississippi river. In 1795 Spain claimed that the land between the Allegheny and the Mississippi belonged to the Indians, and that she had purchased Chickasaw Bluffs of them. She denied our right to free navigation of the Mississippi, stopped goods in transit, levied exorbitant duties, sometimes 50% to 75% ad valorem. She intrigued with influential settlers of Kentucky and Tennessee until it seemed uncertain whether the settlers would become allies of Spain, set up an independent government or involve the United States in war. Numerous outrages, violations of treaty rights and indignities were practiced, and her territory was a harbor for the runaway slave, the escaped criminal and the bandit, Spain pleaded that she could not preserve order within her own territory.

Not to mention the cases of the "Black Warrior" and "Virginius," which we have touched upon, there were more than half a dozen American ships fired upon, overhauled and captured near Cuba from 1877 to 1880. The "Allianca" and "Competitor" cases are fresh in our minds.

In 1877 the "Masonic," an American ship bound for Japan, was forced by stress of weather to put into Manila, where the cargo had to be taken out that repairs might be made. Spanish officers claimed the manifest was not correct and not only violated the treaty, but every rule of hospitality, by confiscating the ship and cargo. The case was arbitrated, and Italy awarded us $56,000 damages about six years after the offense was committed. The Cuban estates of naturalized Americans have frequently been confiscated; Americans have mysteriously died in prison without being brought to trial for any alleged offense; our treaty rights have been flagrantly violated, and Spain's conduct has been aggravating in the extreme.

Although there have been times in our history when the Americans seemed determined to possess Cuba, there have been other times when our support has saved it for Spain. Jefferson, in 1795, said, "We had with sincere and particular disposition courted and cultivated the friendship of Spain;" and in 1823, when France showed a disposition to acquire the island, Clay, as Secretary of State, said, "The United States for themselves desire no change in the political condition of Cuba." Van Buren, in 1840, probably saved the island from England for Spain when he said, "In case of any attempt from whatever quarter to wrest from her this portion of her territory, she may securely depend upon the military and naval resources of the United States to aid in preserving or recovering it." Professor Hart, in Harper's for June, 1898, says:

- "So far from the Cuban policy of the United States having been one of

aggression, few nations have shown more good temper toward a troublesome neighbor, more patience with diplomatic delays or more self-restraint over a coveted possession. The Cuban controversy has not been sought by the United States. It arises out of the

geographical and political conditions of America."

President McKinley's message of April 11, 1898, gives a masterly review of Cuban affairs, and possessing, as he did, information not accessible to the public, nothing can better outline the situation for us.

- The Present Revolution. "The present revolution is but the successor of other similar insurrections which have occurred in Cuba against the dominion of Spain, extending over a period of nearly half a century, each of which, during its progress, has subjected the United States to great effort and

expense in enforcing its neutrality laws, caused enormous losses to American trade and commerce, caused irritation, annoyance and disturbance among our citizens, and, by the exercise of cruel, barbarous and uncivilized practices of warfare, shocked the sensibilities and offended the human sympathies of our people."

Weyler's Policy of Reconcentration

- "The agricultural population, to the estimated number of 300,000 or more, was herded within the towns and their immediate vicinage, deprived of the means of support, rendered destitute of shelter, left poorly clad and exposed to the most unsanitary conditions. As the scarcity of food increased with the devastation of the depopulated areas of production, destitution and want became misery and starvation. Month by month the death rate increased in an alarming ratio. No practical relief was afforded to the destitute. The overburdened towns, already suffering from general dearth, could give no aid. By March, 1897, according to conservative estimates from official Spanish sources, the mortality among the reconcentrados, from starvation and the diseases thereto incident, exceeded 50 per cent of their total number."

The horrible condition of affairs and the increasing destitution having been brought home to the minds of the American people by the speech of Senator Proctor, who had visited Cuba, the public conscience was touched, and in response to an appeal from the President, more than $200,000 was raised by voluntary subscriptions and sent to Cuba for the relief of the reconcentrados, and the civilized world was so impressed that the Spanish government deemed it politic to authorize the appropriation of $600,000 for the same purpose, and ordered the American contribution to be admitted into Cuba free of duty.

The De Lome Incident

Early in February Senor De Lome, the Spanish minister at Washington, had written to Senor Canalejas, then at Havana and a Spanish official of high rank, a letter concerning the situation, certain passages of which were insulting to the President of the United States. The letter made plain that neither De Lome nor Canalejas believed in the sincerity of the "autonomy" proposals, but looked upon them as a blind for diverting the attention of the United States. Some Cuban sympathizer seems to have abstracted the letter from Canalejas and turned it over to the Cuban Junta in New York, who published it in full in the New York Journal. Upon its appearance, De Lome telegraphed his resignation to Madrid, which was immediately accepted, and when our minister, General Woodford, presented the request of the United States for De Lome's recall he was informed that De Lome was no longer a Spanish official.

Destruction of the "Maine"

President Cleveland was exceedingly careful not to wound the sensitive feelings of Spain, and while the Cuban insurrection was in progress American battleships did not visit Cuban ports, neither were the usual South Atlantic fleet maneuvers held. After the granting of so-called autonomy to Cuba and the appointment of officers, the administration saw no reason why the government ships should not resume their friendly naval visits at Cuban ports, especially as there had been rioting in Havana and it was thought the American consulate and the interests of the United States would be furthered by the presence of the battleship, and in accordance with former custom the "Maine," a second-class battleship, visited that port, reaching there about 11 o'clock January 25, 1898. Everything was quiet; no demonstrations were made and the customary formal visits between the officers were exchanged.

The coming of the "Maine" angered the Spanish press and

the volunteers, though outwardly the usual courtesy was shown by

the highest officials. Suddenly, February 15th, at 9:40pm, without

the slightest warning, a terrific explosion occurred on the port side

under the quarters of the crew, and "258 brave sailors and marines

and two officers of our navy, reposing in the fancied security of a

friendly harbor, were hurled to death, grief and want brought to

their homes, and sorrow to the nation."

The coming of the "Maine" angered the Spanish press and

the volunteers, though outwardly the usual courtesy was shown by

the highest officials. Suddenly, February 15th, at 9:40pm, without

the slightest warning, a terrific explosion occurred on the port side

under the quarters of the crew, and "258 brave sailors and marines

and two officers of our navy, reposing in the fancied security of a

friendly harbor, were hurled to death, grief and want brought to

their homes, and sorrow to the nation."

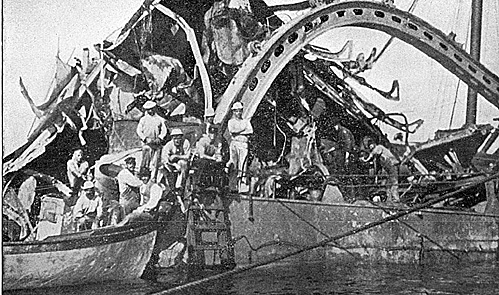

Wreckage of the Maine.

Captain Sigsbee of the " Maine " at once cabled the Navy Department of the disaster and said, "public opinion should be suspended until further reports." The government at Washington at once appointed a Board of Inquiry, consisting of Captain Wm. T. Sampson, of the "Iowa," Captain F. E. Chadwick, of the,, New York," Lieutenant-Commander W. P. Potter, of the " New York," and Adolph Marix, Judge-Advocate of the court, to proceed to Havana as a Court of Inquiry. The wildest rumors were current and excitement at white heat, but following the example set by Captain Sigsbee, the nation with a self-control that excited favorable comment throughout the world, awaited the decision of the Court.

The principal nations were quick to express their sympathy in this awful disaster. At this time the military resources of the United States were at a low ebb. There was not powder enough in the forts of New York to permit of gun practice for the artillery companies. The magazines of the navy were in not much better condition. It was at this stage that selfishness, partisanship and unworthy qualities passed into the background and a wave of patriotism, self-sacrifice and compassion swept over the country.

$50,000,000 for Defense

The Naval Board of Inquiry at once began their work, and as week after week passed without any public expression from them, the tension became severe. While hoping for the best the administration was preparing for the worst. March 8th, the House of Representatives unanimously voted to Place $50,000,000 at the unqualified disposal of President McKinley as an emergency fund for national defense, and the next day the Senate, by a unanimous vote, confirmed the appropriation.

Report of Board

March 22, the Board of Inquiry made their formal report:

- "The discipline and disposition of stores on board the ship was everything that could be desired. That there were two explosions of a distinctly different character with a short interval between them. The forward part of the ship was lifted to a marked degree at the time of the first explosion. The second explosion, in the opinion of the Court, was

caused by the explosion of two or more of the forward magazines of the 'Maine.' A part of the outer wall of the ship 11 1-2 feet from the middle and 6 feet above the keel in its normal position, was forced up so as to be more than 4 feet above the surface of the water and therefore about 34 feet above what it would be if the ship had been sunk uninjured. The outside bottom plating was bent into a reversed V shape (see cut). At frame is the vertical keel is broken in two. This break is now about 6 feet above the surface of the water and about 30 feet above its normal position. In the opinion of the Court this effect could have been produced only by the explosion of a mine situated under the bottom of the ship and somewhat on the port side.

The Court finds that the loss of the 'Maine' on the occasion named was not in any respect due to fault or negligence on the part of any of the officers or members of the crew of said vessel. In the opinion of the Court the ' Maine' was destroyed by the explosion of a submarine mine which caused the partial explosion of two or more of her forward magazines. The Court has been unable to obtain evidence fixing the responsibility for the destruction of the 'Maine' upon any person or persons."

Public Opinion

The horrible tales of suffering sustained by the reconcentrados and the destruction of the "Maine" seemed likely to arouse public opinion to such a pitch that nothing but immediate war would satisfy it. The feeling in the United States was one of genuine sympathy and desire to assist the Cubans. The attitude of Europe was different. With the exception of England the great powers seemed to look upon the Cuban insurrection as something instigated and fostered by the United States for the express purpose of eventually giving this country an excuse to intervene and annex the island.

April 7, ambassadors of the six great powers called on the President and presented an address, and in the name of their governments made:

- "A pressing appeal to the feelings of humanity and moderation of the President and of the American people in their existing differences with Spain. They earnestly hope that further negotiations will lead to an agreement which, while securing the maintenance of peace, will afford all necessary guarantees for the re-establishment of order in Cuba.

The powers do not doubt that the humanitarian and disinterested character of this representation will be fully recognized and appreciated by the American nation."

Although it was an unusual action for the President to grant an audience to more than one ambassador at a time and excited considerable criticism, his sturdy reply sufficiently indicated his position:

- "The Government of the United States appreciates the humanitarian and

disinterested character of the communication now made on behalf of the powers named, and, for its part, is confident that equal appreciation will be shown for its own earnest and unselfish endeavors to fulfill a duty to humanity by ending a situation the indefinite prolongation of which has become insufferable."

The President's Message

April 11th President McKinley sent his famous message to Congress, with consular correspondence. It was strong and conservative. It recited the horrors of Spanish methods and declared that the war must stop. His handling of the question of recognition met with a good deal of criticism, but subsequent events have only proven the wisdom of his position.

- "Nor from the standpoint of expediency do I think it would be wise or prudent for this Government to recognize at the present time the independence of the so-called Cuban Republic. Such recognition is not necessary in order to enable the United States to intervene and pacify the island. To commit this country now to the recognition of any

particular government in Cuba might subject us to embarrassing conditions of international obligation toward the organization so recognized. In case of intervention our conduct would be subject to the approval or disapproval of such government. We would be required to submit to its direction and to assume to it the mere relation of a friendly ally.

"When it shall appear hereafter that there is within the island a government capable of performing the duties and discharging the function of a separate nation, and having, as a matter of fact, the proper forms and attributes of nationality, such government can be promptly and readily recognized, and the relations and interests of the United States with such nation adjusted."

Why We Should Intervene

- 1. In the cause of humanity and to put an end to the barbarities, bloodshed, starvation and horrible miseries now existing there, and which the parties to the conflict are either unable or unwilling to stop or mitigate. It is no answer to say this is all in another country, belonging to another nation, and is therefore none of our business. It is specially our duty, for it is right at our door.

2. We owe it to our citizens in Cuba to afford them that protection and indemnity for life and property which no government there can or will afford, and to that end to terminate the conditions that deprive them of legal protection.

3. The right to intervene may be justified by the very serious injury to the commerce, trade and business of our people, and by the wanton destruction of property and devastation of the island.

4. The present condition of affairs in Cuba is a constant menace to our peace, and entails upon this Government an enormous expense. With such a conflict waged for years in an island so near us and with which our people have such trade and business relations -- when the lives and liberty of our citizens are in constant danger, and their property destroyed and themselves ruined - where our trading vessels are liable to seizure and are seized at our very door by warships of a foreign nation, the expeditions of filibustering that we are powerless to prevent altogether, and the irritating questions and entanglements thus arising -- all these and others that I need not mention, with the resulting strained relations, are a constant menace to our peace, and compel us to keep on a semi-war-footing with a nation with which we are at peace.

On the 13th of April the House Committee of Foreign Affairs reported a resolution, which was adopted the same day by a vote of 322 to 19, directing the President to intervene at once in Cuban affairs, to use the army and navy to carry out the provisions of this act, and further directed him to establish in the island a free and independent government of the people. The House was prepared to support the President; the Senate was determined to grant formal recognition to the insurgents. Several conferences between the House and Senate were held, and finally, in the small hours of the morning of April 19th, the following resolutions were adopted:

- 1. "That the people of the Island of Cuba are, and of right ought to be, free and independent.

2. "That it is the duty of the United States to demand, and the Government of the United States does hereby demand, that the Government of Spain at once relinquish its authority and government in the island of Cuba and withdraw its land and naval forces from Cuba and Cuban waters.

3. "That the President of the United States be, and he hereby is, directed and empowered to use the entire land and naval forces of the United States, and to call into the actual service of the United States the militia of the several States to such an extent as may be necessary to carry these resolutions into effect,

4. "That the United States hereby disclaims any disposition or intention to exercise sovereignty, jurisdiction or control over said island, except for the pacification thereof, and asserts its determination when that is accomplished to leave the government and the control of the island to its people."

The President signed the resolution the next day and prepared and forwarded to the Spanish government an ultimatum giving them three days to accede to our demands. Upon receiving a copy of the President's ultimatum the Spanish minister at Washington asked for his passports, turned Spanish interests over to the French ambassador and left for Canada. Spain detained the ultimatum at the telegraph office until after she could call Minister Woodford, who was informed that the action of the president and Congress was regarded by Spain as a declaration of war, and on the morning of the 21st he was given his passports and escorted as far as the boundary line of France. England has held that the date of war began not with the formal declaration, but April 21st, the day Minister Woodford was handed his passports. The date is important and affects the validity of the capture of prizes.

Friday, April 22, the President issued a call for 125,000 volunteers and declared a blockade of the north coast of Cuba from Cardenas to Bahia Honda, inclusive, and the port of Cienfuegos on the south coast. Just previous to this Rear Admiral Sicard in command of the North Atlantic fleet at Key West had been retired and the command was given to Capt. William T. Sampson, who was made acting rear-admiral. The fleet consisted of the following vessels:

- Battleships Iowa, Capt. Evans ; Indiana, Capt. Taylor. Monitor Amphitrite, Capt. Barclay. Armored cruiser New York, Capt. Chadwick. Protected cruiser Cincinnati, Capt. Chester. Unprotected cruiser Detroit, Commander Dayton. Gunboats Wilmington, Commander Todd; Helena, Commander Swinburne; Nashville, Commander Maynard ; Castine, Commander Perry; Machias, Commander Merry ; Newport, Commander Tilley. Dynamite cruiser Vesuvius, Lieut.-Commander Pillsbury. Torpedo boats, Ericsson, Lieut.

Usher ; Foote, Lieut. Rogers ; Winslow, Lieut. Bernadou ; Hawk, Lieut. Hood; Hornet, Lieut. Helm; Maple, Lieut.-Commander Kellogg ; Osceola, Lieut. Purcell ; Scorpion, Lieut.-Commander Marix ; Vixen, Lieut. Sharp: Wasp, Lieut. Ward; Wampatuck, Lieut. Jungen; Sioux, Ensign Charardi ; Nezinscott, Mate Cleveland. Tug Leyden, Boatswain Angus, of the auxiliary fleet.

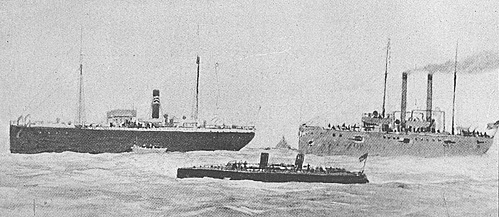

Before daylight Friday morning the fleet was in motion. At six o'clock, the Spanish steamer Buena Ventura,

the first prize, was captured by the Nashville, Patrick Mallia,

gunner, having the honor of firing the first gun in the war.

Before daylight Friday morning the fleet was in motion. At six o'clock, the Spanish steamer Buena Ventura,

the first prize, was captured by the Nashville, Patrick Mallia,

gunner, having the honor of firing the first gun in the war.

From left to right: Spanish ship Buena Ventura, US torpedo boat Winslow, and US gunboat Nashville.

At 1pm that day Havana was completely blockaded and soon numerous prizes of the American vessels began to make their appearance at Key West.

Operations Before Manila

About the same time Commodore George Dewey, commanding the Asiatic squadron at Hong Kong, was ordered to find and destroy the Spanish fleet. He had under his command the Olympia (flagship), Baltimore, Boston, Concord, Raleigh, Petrel and the revenue cutter McCulloch. Commodore Dewey got under way without loss of time, left Mirs Bay April 27, and steered straight for the Philippines. Saturday, April 30th, he arrived off Subig Bay, some 30 miles north of Manila. The Boston, Baltimore and Concord reconnoitered the Bay looking for the Spanish fleet. Not finding them, the squadron headed for Manila Bay, taking care to arrive, off the entrance after dark. The entrance is about six miles wide, and divided by Corregidor Island, where batteries were mounted, into two channels the larger and the smaller.

Early Sunday morning before light, formed in line of battle, they started through the smaller channel. The "Olympia" was leading, followed by the "Baltimore," "Raleigh," "Petrel," "Concord," and the "Boston;" then the second line, made up of the revenue cutter " McCulloch " and the transports " Naushan " and "Zarifo." The entrance was guarded by fortifications mounting heavy guns and the channel was supposed to be defended by mines. The Spanish maps on which the navigators had relied proved to be worthless, but with their men at quarters and their guns trained in the direction of the batteries, they proceeded silently on the way, knowing every moment that they might be blown into eternity, and expecting that the guns of Corregidor Island would certainly open on them, but there was only a silence so intense as to be awful in its strain. The "Olympia," the "Baltimore," the "Raleigh," the "Petrel" and the "Concord" had passed without discovery, when flames from the funnels of one of the ships attracted a sleepy sentinel.

A bugle rang out, a rocket shot up, a flash, and a shot flew

across the water. The "Boston" opened fire at the fort, which

replied, but the fleet had passed the guard. They now slowly made

a circuit of the bay, and when morning broke were off the city of

Manila, but found no signs of the Spanish fleet there. Steaming

slowly on, they soon came upon them drawn up in a small bay

flanked by the heavy batteries of Cavite arsenal.

A bugle rang out, a rocket shot up, a flash, and a shot flew

across the water. The "Boston" opened fire at the fort, which

replied, but the fleet had passed the guard. They now slowly made

a circuit of the bay, and when morning broke were off the city of

Manila, but found no signs of the Spanish fleet there. Steaming

slowly on, they soon came upon them drawn up in a small bay

flanked by the heavy batteries of Cavite arsenal.

Color Illustration: Battle of Manila (slow: 158K)

Jumbo Color Illustration: Battle of Manila (monstrously slow: 885K)

About 5 o'clock the enemy opened fire. Dewey signaled his ships to close up, and turning to Captain Gridley of the "Olympia" said, "Any time when you are ready, Gridley." Gridley was ready and almost instantly the forward 8-inch guns spoke with a terrific crash. The smoke and sprinters could be seen flying from the Spanish ship opposite, and a battle that is likely to change the destiny of this nation had begun.

- "The squadron then proceeded to the attack, the flagship Olympia, under my personal direction, leading, followed at a distance by the Baltimore, Raleigh, Petrel, Concord and Boston in the order named, which formation was maintained through the action. The squadron opened fire at 5: 41 A. M. While advancing to the attack two mines were exploded ahead of the flagship, too far to be effective. The squadron maintained a continuous and precise fire at ranges varying from 5,000 to 2,000 yards, countermarching in a line approximately parallel to that of the Spanish fleet. The enemy's fire was vigorous, but generally ineffective.

Early in the enagagement two launches put out toward the Olympia with the apparent intention of using torpedoes. One was sunk and the other disabled by our fire and beached before they were able to fire their torpedoes.

At 7am the Spanish flagship Reina Christina made a desperate attempt to leave the line and come out to engage at short range, but was received with such a galling fire, the entire battery of the Olympia being concentrated upon, her, that she was barely able to return to shelter of the point. The fires started in her by our shell at the time were not extinguished until she sank. The three batteries at Manila had kept up a continuous fire from the beginning of the engagement, which fire was not returned by my squadron. The first of these batteries was situated on the south mole head at the entrance of the Pasig river, the second on the south portion of the walled city of Manila, and the third at Molate, about one-half mile further south.

At this point I sent a message to the Governor-General to the effect that if the batteries did not cease firing the city would be shelled. This had the effect of silencing them.

At 7: 45am I ceased firing and withdrew the squadron for breakfast. At 1l:16 I returned to the attack. By this time the Spanish flagship and almost all the Spanish fleet were in flames. At 12:30 the squadron ceased firing, the batteries being silenced and the ships sunk, burned and deserted.

At 12:40 the squadron returned and anchored off Manila, the Petrel being left behind to complete the destruction of the smaller gunboats, which were behind the points of Cavite. This duty was performed by Commander E. P, Wood in the most expeditious and complete manner possible.

I am happy to report that the damage done to the squadron under my command was inconsiderable. There were none killed and only seven men in the squadron were slightly wounded. Several of the vessels were struck and even penetrated, but the damage was of the slightest, and the squadron is in as good condition now as before the battle,

I beg to state to the Department that I doubt if any commander-in-chief was ever served by more loyal, efficient and gallant captains than those of the squadron under my command. Captain Frank Wildes, commanding the Boston, volunteered to remain in command of his vessel. although his relief arrived before leaving Hong Kong. Assistant Surgeon Kindelberger, of the Olympia, and Gunner J. J. Evans, of the Boston, also volunteered to remain after orders detaching them had arrived. The conduct of my personal staf. was excellent. Commander B. P. Lamberton, chief of staff, was a volunteer for that position, and gave me most efficient aid. Lieuienant Brumby, flag lieutanant, and Ensign E. P. Scott, aide, performed their duties as signal officers in a highly creditable manner. Caldwell, flag secretary, volunteered for and was assigned to a subdivision of the 5-inch battery. Mr. J. L. Stickney, formerly an officer in the United States Navy, and now correspondent for the New York Herald,' volunteered for duty as my aide, and rendered valuable service. I desire especially to mention the coolness of Lieutenant C. G. Calkins, the navigator of the Olympia, who came under my personal observation, being on the bridge with me throughout the entire action, and giving the ranges to the guns with accuracy that was proven by the excellence of the firing.

On May 2, the day following the engagement, the squadron again went to Cavite, where it remains. On the A the military forces evacuated the Cavite arsenal, which was taken possession of by a landing party. On the same day the Raleigh and Baltimore secured the surrender of the batteries on Corregidor Island, parolling the garrison and destroying the guns. On the morning of May 4 the transport Manila, which had been aground in Baker Bay, was towed off and made a prize."

- (--Admiral Dewey's Official Report.)

The comparison of the losses in this battle is startling. Two officers and six men on board the "Baltimore" were slightly wounded, the Only casualties on the side of the Americans. The Spaniards lost 101 killed and 280 wounded. . There were destroyed two protected cruisers, five unprotected cruisers, a transport and a sering vessel, two vessels captured and other property captured and destroyed, all estimated to be worth about $6,000,000. The damage to the American fleet did not exceed $5,000.

The news of the victory electrified the world. Its effect in Europe was especially marked. A Spanish fleet defended by land batteries had been attacked and destroyed without loss of life to the assailants, an entrance to a harbor supposed to be almost inpregnable had been passed without loss and almost without discovery. The effect of the victory on the future of this country must certainly be a marked one. It has opened up to us the possibility of a "new national policy," and more than any other event seems to have aroused the American ambition for a wider sphere in international affairs.

Arrangements for the organization of a force of 20,000 men under the command of General Wesley Merritt were at once made and reinforcements hastened to the assistance of Admiral Dewey with the greatest possible dispatch. He had brought with him in the "McCulloch" from Hong Kong the rebel leader Aguinaldo, who at once proceeded to put himself in communication with the natives and organized the insurgents with himself at their head. He soon became so ambitious as to be a dangerous ally, declared himself " Dictator," and took to wearing a gold collar with a gold whistle. He was a strange mixture of shrewdness, diplomacy and childishness. He at times assisted the Americans and at other times refused them supplies. What he will do in the future remains to be seen.

The Germans had been looking with longing eyes at the Philippine Islands and seized the opportunity, under cover of protecting German interests, to send a strong force of war vessels to Manila, where they rendered themselves obnoxious by a very evident sympathy with the Spanish cause and overbearing manners. Admiral Dewey exercised great tact, preserved control of the situation under the most trying circumstances, avoided any open rupture, and maintained the dignity of the United States. The firm stand taken by Admiral Dewey and the arrival of the first expedition of reinforcements under General Anderson, left the Germans no further excuse, and they withdrew.

An incident at Subig Bay threatened to attain international importance. The German cruiser "Irene" had refused to allow the insurgents to attack a Spanish position in Subig Bay. July 7th, Dewey sent the " Raleigh " and " Concord " to that point. As soon as the " Raleigh " opened fire on the fort the German cruiser discreetly withdrew. Fifteen hundred Spaniards surrendered without much resistance. The commander of the " Irene " said he had interfered in the cause of humanity, and offered to hand over to Dewey certain refugees, but his offer was declined.

The cruiser "Charleston," convoying three transports of the first relief expedition, reached Cavite June 30th. On the way they stopped at the island Guam, one of the Ladrones, took possession of it, left a company of the Fourteenth artillery in charge, and carried the governor, Spanish officers and 54 soldiers as prisoners of war to Manila. Admiral Dewey was reinforced by the double turreted monitors " Monadnock " and " Monterey " and the cruiser "Charleston."

General Merritt upon his arrival extended his line before the city and was vigorously attacked July 31st, losing 13 dead and 47 wounded. The Spaniards were repulsed with great loss. It is likely that considerable trouble will be experienced in preserving order there until some settled form of government shall have been agreed upon.

Matanzas

The first engagement of the American navy with Spanish forts occurred April 27th, when three vessels of Admiral Sampson's fleet, the "New York," the monitor " Puritan " and the cruiser " Cincinnati," exchanged shots with the batteries at Matanzas. The ships fired about 300 shots at a range of from 3,500 to 7,000 yards. The damage to the enemy was probably insignificant. General Blanco reported it as one mule killed. None of our vessels were hit. Though the affair excited considerable comment at the time, it was important only in giving our men some target practice and demonstrating that the Spaniard is the poorest gunner on earth.

Reverse at Cardenas

The most serious reverse sustained by the American navy was that at Cardenas, May 11th, when the unprotected cruiser "Wilmington," the gunboat "Machias," the revenue cutter " Hudson," and the torpedo boat "Winslow," made an attack on that port for the purpose of cutting out three small gunboats in the harbor. The draft of the "Wilmington" would not allow her to approach nearer than 2,000 yards, and as the gunboats could not be seen at that distance the "Winslow" was ordered to go in and find them. The torpedo boat had gone about 700 yards when she was fired upon by a gunboat and a shore battery. There was a sharp exchange of shots for about twenty minutes, when it became evident that the "Winslow" was disabled. Lieutenant Newcomb of the revenue cutter "Hudson," gallantly steamed in under fire, took the "Winslow" in tow, and brought her out in safety.

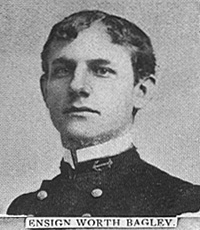

The "Winslow" was disabled, one officer, Ensign Worth

Bagley, and four men killed, and three men wounded, including

Lieutenant Bernardo, commander of the " Winslow." In this brave but ill-advised attempt we suffered a greater loss than in the naval

victories at Manila and off Santiago combined.

The "Winslow" was disabled, one officer, Ensign Worth

Bagley, and four men killed, and three men wounded, including

Lieutenant Bernardo, commander of the " Winslow." In this brave but ill-advised attempt we suffered a greater loss than in the naval

victories at Manila and off Santiago combined.

Bombardment of San Juan

May 12th, Admiral Sampson's squadron, consisting of the battleships " Iowa " and "Indiana," the armored cruiser "New York," the monitors " Terror " and "Amphitrite," and the cruisers Detroit " and " Montgomery," with the torpedo boat Porter," in search of the Cape Verde fleet, arrived off San Juan, Porto Rico. They entered the harbor, and not finding Cervera, engaged in some target practice with the fortifications and reported them silenced. The fleet suffered little damage -- the " New York " and the " Iowa " each being hit once, one man killed and six wounded.

Though the action itself was a minor one, it was important in shaping the course of Cervera's fleet. He, hearing that Sampson was at San Juan, pushed on to Curacoa, an island about 75 miles from the Venezuela coast, belonging to the Netherlands. Cervera was unable to obtain any coal there, and being short of fuel, ran into Santiago, where Commodore Schley "bottled him up." Coal is not uniformly held to be contraband of war. Perhaps the Dutch inhabitants remembered the treatment their ancestors had received at the hands of the Duke of Alva.

The Santiago Campaign

Admiral Cervera's fleet left the Cape Verde Islands April 25th, and for two weeks his movements were shrouded in mystery. The Atlantic cities feared attack, the blockade of Havana was likely to be raised, and the invasion of Cuba could not take place while such a powerful " fleet in being " was in existence. All offensive movements were paralyzed.

On May 13, news was received that Cervera's squadron had been sighted off Martinique and on the 15th it was heard of at the island of Curacao. On the 13th, Commodore Schley's "flying squadron" left Hampton Roads and steamed southward. Admiral Sampson's fleet left San Juan on the 15th, headed toward Cuba along the northern coast of San Domingo. The auxiliary scouts and the fleet cruisers " Columbia " and " Minneapolis " were searching for the Spanish fleet in mid-ocean. Information was received the 19th that Cervera had reached Santiago, and Commodore Schley was ordered from Cienfuegos, off which port he had arrived the 21st, to proceed at once to Santiago and blockade the narrow entrance to the harbor. He was able to report the 28th that he had seen and recognized the Spanish fleet in the bay of Santiago, and Lieutenant Blue was landed some distance from Santiago and alone made a perilous trip over the mountains to where he could see the harbor and recognize the fleet. All doubt was set at rest and the nation drew a breath of relief.

The invasion of Cuba, which had been delayed, went forward vigorously. May 31st, Commodore Schley's squadron had the honor of engaging in a skirmish with the batteries about the entrance to the harbor and with the " Cristobal Colon " in the background. Admiral Sampson joined Commodore Schley June 1st and assumed command of the fleet. A vigilant blockade was kept up.

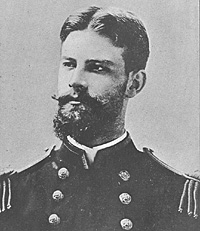

At three o'clock A. M. June 3rd, Assistant Naval Constructor

Richmond P. Hobson (at right), with a crew of seven men, took the collier "

Merrimac " into the narrow entrance of Santiago harbor under the

fire of the guns from the Spanish forts and fleet, over the mines,

and sunk her across the channel. No braver feat is recorded in the

history of naval warfare. It was hoped the sunken ship would

temporarily close the channel and prevent the exit of Cervera's

fleet. Lieutenant Hobson and his men miraculously escaped serious

injury, left the sunken ship on a raft, but were captured.

At three o'clock A. M. June 3rd, Assistant Naval Constructor

Richmond P. Hobson (at right), with a crew of seven men, took the collier "

Merrimac " into the narrow entrance of Santiago harbor under the

fire of the guns from the Spanish forts and fleet, over the mines,

and sunk her across the channel. No braver feat is recorded in the

history of naval warfare. It was hoped the sunken ship would

temporarily close the channel and prevent the exit of Cervera's

fleet. Lieutenant Hobson and his men miraculously escaped serious

injury, left the sunken ship on a raft, but were captured.

Admiral Cervera sent an officer under a flag of truce to Admiral Sampson, telling him the men were all alive and offered to carry back to the prisoners messages and clothing. They remained as prisoners in Santiago until July 6th, when their exchange was effected by Gen. Shafter, Admiral Cervera saying at that time: "Daring like theirs makes the bitterest enemy proud that his fellow men can be such heroes."

The American fleet did not attempt to force the entrance.

The channel was too narrow, the batteries too strong and situated at too great a height, the attitude of jealous European powers too equivocal to permit the risk of the loss of a battleship. The action of the fleet was confined to occasional bombardments and a vigilant blockade that rendered escape for Cervera hopeless.

Landing at Guantanamo

To secure a position for our ships to use when coaling Lieutenant-Colonel Huntington with about 600 marines landed June 10th at Guantanamo. The landing was made under the protection of the guns of several vessels from Admiral Sampson's fleet. The country was covered with dense thickets of tropical growth, under cover of which Spanish soldiers and guerrillas kept up unceasing bushwhacking attacks. Unacquainted with the field and confined to the locality of the camp, our marines were at a serious disadvantage, although their efforts were ably seconded by the small body of Cuban insurgents which joined them. For two or three days the skirmishing was almost constant, but the little force of Americans held the ground secured and inflicted heavy loss on the enemy. Early Sunday morning the Spaniards made an attempt to rush the camp, but were driven back with severe loss. The " Texas " arrived and landed 40 marines with two Colt automatic guns and the " Marblehead " moved up and shelled the wooded hillside where the Spaniards were concealed. Again on the morning of the 13th the Spaniards tried to rush the camp, but with no better success. On the 14th, our forces somewhat strengthened, adopted an aggressive policy, sent out four columns and were soon actively engaged with the enemy. The Cuban insurgents rendered material service. The combined forces beat up the surrounding country, drove the enemy from the thickets, inflicted upon him a severe loss and captured one Spanish officer and seventeen privates. From this time the situation at Camp McCalla was greatly improved, entrenchments were thrown up, more Cuban reinforcements arrived, the war vessels gave their support, and the outer bay was securely held. The marines held their position, and the harbor has afforded a safe base of operations for Admiral Sampson's fleet.

The Destruction of Cervera's Fleet

Admiral Cervera made a dash out of the harbor 9:35 A. M. Sunday, July 3. At this time the flagship "New York" was about seven miles from the entrance, Admiral Sampson having started to consult with General Shafter. The " Massachusetts " was coaling at Guantanamo and the others were in their usual blockading position, from two and one-half to four miles from the entrance, in the following order from eastward to westward: "Indiana," "Oregon," "Iowa," "Texas," and "Brooklyn." The auxiliaries "Gloucester" and "Vixen" lay close to the land and nearer the harbor entrance than the large vessels, the " Gloucester " to the eastward and the " Vixen " to the westward. The torpedo boat " Ericsson " was in company with the flagship.

- The Spanish vessels came rapidly out of the harbor at a speed estimated at from eight to ten knots and in the following order: "Infanta Maria Teresa," (flagship), "Viscaya," " Cristobal Colon," and " Almirante Oquendo."....Following the " Oquendo " came the torpedo boat destroyer " Pluton " and after her the "Furor." The men of our ships were at Sunday quarters for " inspection ; the signal was made simultaneously from several vessels, "the enemy's ships escaping" and "general quarters" were sounded. The men cheered as they sprang to their guns and fire was opened probably within eight minutes by the vessels whose guns commanded the entrance. The "New York" turned about and steamed for the escaping fleet flying the Signal "close in toward harbor entrance and attack vessels."

She was not at any time within the range of the heavy Spanish ships and her only part in the firing was to receive the individual fire from the forts in passing the harbor entrance and fire a few shots at one of the destroyers thought at the moment to be attempting to escape from the "Gloucester." The Spanish vessels upon clearing the harbor turned to the westward in column, increasing their speed to the full power of their engines.

The initial speed of the Spaniards carried them rapidly past the blockading vessels and the battle developed into a chase in which the " Brooklyn " and " Texas " had at the start the advantage of position. The " Brooklyn " maintained this lead.

Anticipating the appearance of the " Pluton " and the " Furor " the " Gloucester " was slowed, thereby gaining more rapidly a high pressure of steam, and when the destroyers came out, she steamed for them at full speed and was able to close at short range where her fire was accurate, deadly and of great volume.

Within twenty minutes from the time they emerged from Santiago harbor the careers of the " Pluton " and " Furor " were ended and two-thirds of their people killed. The " Furor " was beached and sunk in the surf; the " Pluton " sank in deep water a few minutes later. After rescuing the survivors of the destroyers, the "Gloucester" did excellent service in landing and securing the crew of the "Infanta Maria Teresa."

- (Admiral

Sampson's Official Report)

The Spanish cruisers suffered heavily in passing our battleships, and the " Maria Teresa " and " Oquendo " were set on fire during the first fifteen minutes of the engao-ement; the former had her fire main cut by one of our first shots, a second set her on fire, and a third disabled one of her engines. Six and a half miles from Santiacro harbor the " Maria Teresa " ran in on the beach, and a half mile farther on the " Oquendo " did the same. The Vizcaya was beached at Acerraderos, 15 miles from Santiago, at 11:15. She was burning fiercely, and her reserves of ammunition on deck were beginning to ex. plode.

- There remained now of the Spanish ships only the " Cristobal Colon," but she was their best and fastest vessel.

When the Vizcaya " went ashore the " Colon " was about six miles ahead of the "Brooklyn" and "Oregon," but her spurt was finished and the American ships were now gaining upon her. Behind the " Brooklyn " and " Oregon " came the " Texas," "Vixen" and "New York."

At 11:50 the "Brooklyn" and " Oregon " opened fire and got her range, the " Oregon's " heavy shells striking beyond her, and at 1:20 she gave up without firing another shot, hauled down her colors and ran ashore at Rio Torquino, 48 miles from Santiago.

The "Iowa," assisted by the " Ericsson " and the "Hist," took off the crew of the "Vizcaya," while the "Harvard" and " Gloucester " rescued those of the " Infanta Maria " and Almirante Oquendo." This rescue of prisoners, including the wounded from the burning Spanish vessels, was the occasion of some of the most daring and gallant conduct of the day. The ships were burning fore and aft, their guns and reserve ammunition were exploding, and it was not known at what moment the fire would reach the main magazine. In addition to this a heavy surf was running just inside of the Spanish ships, but no risk deterred our officers and men until their work (if humanity was completed.

The fire of the battleships was powerful and destructive, and the resistance of the Spanish squadron was in great part broken almost before they had gone beyond the range of their own forts. The fine speed of the " Oregon " enabled her to take a front position in the chase, and the " Cristobal Colon " did not give up until the " Oregon " had thrown a 13-inch shell beyond her.

- (Admiral Sampson's Official Report)

Although the destruction of the Spanish ships was so rapid and so thorough, very little damage was done the American squadron. The " Brooklyn " was hit more often than the others, but very slight damage was done, the greatest being to the " Iowa." The American loss was one man killed and one wounded, both on the "Brooklyn."

The Spanish plan of escape, so far as the ships were concerned was feasible, and had the Spanish fleet been in American hands, and vice versa, it would have undoubtedly been successful. The four Spanish cruisers were all Of 20-knots speed, and the destroyers were supposed to be good for 28 to 30, knots. Against them were the " Iowa," 17.1 knots, "Oregon," 16.8 knots, "Texas," 17.8 knots, and the "Brooklyn," 21.9 knots. American gunnery won the day and won it in very short order. Santiago adds its eloquent testimony to the truth that today as of old, it is "the man behind the gun" that wins the fight. The moment Cervera's fleet was found, its destruction became necessary.

Shafter's Army

June 14th, Maj.-Gen. Shafter, commanding the 5th Army Corps of about 16,000 men, made up of all branches of the service, left Tampa for an attack on Santiago.

The force was composed wholly of regulars, except the 71st New York, the 2d Massachusetts and the 1st Volunteer Infantry (Rough Riders). They embarked on 35 transports with two water boats and with a strong., convoy, headed by the battleship " Indiana," proceeded eastward along the north coast of Cuba around the eastern point, Cape Maysi, and arrived off Santiago June 20th.

The expedition was remarkable in moving without an unpleasant occurrence, and was the largest of its kind since the Crimean war. Upon his arrival General Shafter with Admiral Sampson met Lieut.-Gen. Garcia, commanding about 4,000 Cubans, and made plans for a landing and attack on Santiago. On the 22d the fleet kept up a series of demonstrations along the coastfor20 miles, and so completely deceived the Spaniards that the army was landed in the face of a force nearly as great as its own without the loss of a single life. The harbors were shallow, the shores were rocky, the lighters usually thought necessary for such operations had sunk on their way to Cuba, yet in the face of all these difficulties the first landing was made the 22d at Daquiri, on the 23d another at Sibonev.

On the 24th the landing of troopscontinued, and an advance early in the morning reached La Guasina, four miles west of Siboney, where an action occurred. The ist and ioth cavalry charged in front, the ist Volunteer Cavalry charged in flank on the left and drove the enemy from his position, although we sustained a severe loss in killed and wounded. By nightfall a gain of more than a mile had been made. The troops in this action were under the command of Gen. Young.

By June 25th our forces, Gen. Lawton's division in advance, occupied the high ridge of Savilla in full view of Santiago, distant about five miles. Gen. Wheeler's dismounted cavalry was some distance behind Lawton's division, Kent's division coming up in the rear of Wheeler's. By the 27th they had forced their way to points within three miles of Santiago. The light batteries came up and took position near Wheeler's division, about the center of the army as it then stood, the mounted squadron of the Second Infantry occupying a position near the battery.

Battle of El Caney

June 30th, Gen. Lawton, commanding the Second Division, made a reconnaissance of the village of El Caney. Gen. Shafter held a consultation and issued orders for an attack on the village July 1st with the object of passing through and turning the flank of the enemy.

The troops were pushed forward, moving at night by the light of the moon, and one battery of artillery reached a point commanding El Caney. About 7 A. M. the artillery opened fire at a range of 2,400 yards. They were out of range of the small arms and the enemy had no artillery. The engagement became general, and the fire was hot until 10am, during which time all the lines were drawing closer to the enemy and a continuous fire of musketry being kept up. By afternoon they had closed in on the village.

A stone fort or block-house situated on the highest point at the northern side commanded the fields, the fire of the artillery was concentrated on this, and between i and 2 o'clock an assault made by the infantry under Chaffee, Bates and Miles, carried the position. The small block-houses on the other side of the village kept up a fierce resistance, but were soon silenced by our infantry fire before the artillery could be brought to bear upon them. By night our troops occupied the main road leading into the city of Santiago.

Battle of San Juan

July 1st found Wheeler's division bivouacked on the heights of El Pozo and Kent's division to his left near the road back of El Pozo. At 6:45 A. M. the first guns against El Caney were heard, and a little later Grimes' battery opened against San Juan. By 9 o'clock Wheeler's division was in march toward Santiago. Continued skirmishing was kept up until the stream Aguadores was crossed, when the enemy opened volley fire against the dismounted cavalry who were going into position and crossing open ground. Kent's division followed Wheeler's, turning, to the left and advancing under a severe fire. At one o'clock the whole force advanced, charged, and carried the enemy's first line of entrenchments. Here they halted and threw up a line of entrenchments facing the enemy, who were only 500 to 1,000 yards distant.

The cavalry division occupied the captured crest, and regiments of Kent's division moved to the left. Gen. Bates, Independent Brigade after taking part in the battle of El Caney was moved back and went into position July 2d, at the extreme left of the lines.

Before Santiago

During the whole Of July 2d, heavy firing was kept up by both sides. Our troops were busy throwing up entrenchments to sustain their positions. Batteries of artillery going into action near San Juan, 600 yards from the enemy and firing black powder, were soon located and driven back with heavy losses. During this day there were many losses from hits made at extreme range, the bullets passing over the crest held by our first line and striking those in the rear. Spanish sharp shooters hidden in treetops within our own lines inflicted severe loss and did not respect the wounded or hospital corps.

The night of July 2d, the enemy made an attack upon our lines, but were driven back with very little loss to ourselves. It. was evident that the city was doomed. On the morning of July 3rd, there was little firing on either sides, and the Spanish fleet left the harbor and were destroyed. The next ten days were taken up with negotiations for the surrender and a desultory firing.

The army and city capitulated on the 14th of July, Gen. Toral surrendering all the territory and forces in eastern Cuba, including about 12,000 soldiers who had never fired a gun against us, the United States agreeing to transport the Spanish soldiers to Spain, the officers to retain their side arms, and the officers and men their personal property. The Spanish commander was allowed to take the military archives belonging to his district. The Spanish volunteers and guerillas were allowed to remain upon giving their parole and surrendering their arms.

The Spanish forces marched out with the honors of war and deposited their arms at a point mutually agreed upon. The number of troops surrendered amounted to more than 24,000. July 17, General. Shafter reported to Washington as follows:

- "I have the honor to announce that the American flag has been this instant, 12 o'clock noon, hoisted over the house of the Civil Government. An immense concourse of people was present, a squadron of cavalry and a regiment of infantry presenting arms and a band playing national airs. A light battery fired a salute of twenty-one guns."

Invasion of Porto Rico

Soon after the fall of Santiago, Gen. Miles left with an army for Porto Rico. A landing was made July 25th on the south coast at Guanica, fifteen miles west of Ponce, and the port and town captured without loss, the inhabitants receiving them with open arms. Soon after Ponce, a city of 50,000 inhabitants, and the largest in Porto Rico, surrendered, the populace receiving the troops and saluting the flag with wild enthusiasm.

The march inland was taken up in four columns, town after town falling into our hands after only light skirmishes, the Spanish soldiers surrendering or falling back and the inhabitants showing the greatest pleasure at the appearance of the American troops. Peace negotiations closed the war without heavy fighting in Porto Rico.

Peace Negotiations

The overtures of peace were made public August 2d. They stipulated that Spain should give up all claim to the island of Cuba, and cede to the United States, Porto Rico and an island in the Ladrones. Furthermore, the United States should occupy and hold Manila and surrounding territory pending the conclusion of a treaty of peace which should determine the final disposition of the Philippines. If these terms were accepted by Spain, commissioners of the United States would meet commissioners of Spain for the purpose of concluding a treaty of peace.

Sagasta summoned the heads of all parties to confer with him August 3d. The Ministry was in favor of peace, but uncertain of its power to make peace. Finally, on the evening of August 8th, Spain's answer was received and presented to the President through Monsieur Cambon, the French ambassador. In it she accepted our terms with the qualification that the protocol should contain certain concessions with regard to the withdrawal of the Spanish troops from Cuba, the disposition of the Cuban debt, and other subjects of controversy.

On August 10th the protocol was drawn up, and in it no provision was made with regard to the exceptions given by Spain in her note. Monsieur Cambon agreed provisionally to the terms of the protocol in behalf of Spain, and cabled to Madrid for authority to attach his signature to the document as Spanish representative. The terms of the protocol were essentially the same as those forwarded to Spain ten days before, and the Spanish Ministry declared itself satisfied. Bya brilliant diplomatic coup, President McKinley and Secretary Day had placed the Spanish Ministry in a pos.*tion where they could no longer parley nor procrastinate.

In one hundred days Spain lost two fleets, an army and all her possessions in this hemisphere, and America stood forth a great "world power."

Second Battle of Manila

The same day the protocol was signed, President McKinley issued a proclamation announcing a general suspension of hostilities, and hurried off instructions to the various army and navy leaders at their different stations, but before the news reached Dewey at Manila a second battle had been fought. Almost a week before, Admiral Dewey and General Merritt had given the Spanish commander notice to remove all noncombatants. (see Appendix)

A later demand for the surrender of the city having been refused, the fleet opened fire about 8:30 A. m., August 13, great care being observed to prevent any shot falling into the city proper. The enemy received the fire of the fleet without making any response.

Meanwhile the land forces were moving in two columns upon the Spanish works. A spirited action ensued, but the Spanish forces were unable to hold their position and retreated with heavy loss, leaving part of their line of defense in the possession of their opponents, who had suffered a loss of about 12 men killed and 40 wounded.

Spain foreseeing the disaster had, with characteristic diplomacy, technically " relieved " Captain General Augustin, for the express purpose of leaving no Spanish officer having jurisdiction over the whole group of islands, and the command of Manila had devolved upon General Jaudenes. This commander realizing the hopelessness of his position signified a willingness to come to terms.

The negotiations were carried on through the Belgian consul, who, with Flag Lieut. Brumby of the Olympia and Lieut. Col. Whittier of the army, went ashore from the flagship. Upon their return a white flag appeared on the Spanish fort, and General Merritt, with a military escort, went ashore to receive the surrender of the city. The Spanish flag that for more than 350 years had floated over the Philippines as the symbol of sovereignty came down, and Lieut. Brumby had the honor of hoisting an American flag from the Olympia in its stead.

Captain General Augustin, by the connivance of the German Admiral, escaped on board the German warship "Kaiserin Augusta." The insurgents had remained spectators of the combat, and greatly to their disgust were not allowed to plunder the city.

Spain had hoped that the Peace Commission would find her still in possession of Manila when she would have claimed that the city could have held out indefinitely. A dispatch from Madrid announcing the peace negotiations was sent to the Spanish commander August 13, but the American flag, if allowance for difference in time is made, was then floating over the city, and even if the cable had been working, between Manila and Hong Kong, the dispatch would have been too late.

The advantage of control of Manila thus passed to America.

Occupation of Porto Rico

Porto Rico was invaded on the south, it appearing to be a part of General Miles' plan to drive all the enemy I s forces before him and to leave open for them lines of retreat to San Juan on the north coast. There he expected to gather them in, leaving the whole island in the peaceable possession of the Americans, for four-fifths of the inhabitants evinced the greatest pleasure at the prospect of a change of government.

The campaign lasted nineteen days during which time there were five encounters rising to the dignity of skirmishes. Although the contour of the country offered many opportunities for defense, the Americans were uniformly and easily successful. Ensign Curtin of the "Dixie" landed at the port of Ponce, called the commander of the town proper to the telephone and demanded his surrender, which was yielded. About the only show of spirited defiance by a Spanish officer was the reply of Lieut. Col. Nuvillers to General Wilson's demand for his surrender, "Tell General Wilson to stay where he is if he wishes to avoid further bloodshed." The cessation of hostilities rendered an attack on Colonel Nuvillers unnecessary.

Porto Rico thus easily fell into the hands of the Americans. It had been a Spanish possession for more than 400 years, but a large majority of its inhabitants were overjoyed at their escape from the evils of Spanish administration.

Evacuation and Peace Commissions

Agreeable to the terms of the protocol, each nation named within ten days members of the commissions, who were to meet within thirty days and arrange all the details of the evacuation of Cuba and Porto Rico.

President McKinley named as members of the Cuban commission, Maj.-Gen. Jas. F. Wade, Rear Admiral William T. Sampson and Maj.-Gen. M. C. Butler. Captain-General Blanco refused to serve on the commission, and Spain named his second in command, General Parrado, together with Captain Landera and the leader of the Cuban Autonomists, the Marquis Montoro.

The American members of the Porto Rican board were Maj.-Gen. John R. Brooke, second in command in Porto Rico; Rear Admiral Winfield S. Schley, and Brig.Gen. William W. Gordon. The Spanish members were General Ortega, Captain Vallarino and Senor Sanches Aquila.

By the terms of the protocol, the Peace Commission was composed of ten members, to meet in Paris before October 1, and America very properly headed her delegation with William R. Day, who had rendered such distinguished service as Secretary of State. Judge Day is popularly credited with being the author of the protocol of August 12. Judge Day's associates on the commission were Senator Cushman K. Davis, Senator William P. Frye, Whitelaw Reed of the New York Tribune, and Justice White of the Superior Court.

Our country has assumed new and heavy responsibilities, but there is little ground for fear that she will not rise to the occasion.

Next: Chapter 15: Appendix: Peace Protocol and Costs

Back to The Passing of Spain Table of Contents

Back to Spanish-American War Book List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com