Development of the Ironclad

The idea of armor for ships is an old one. The galleys of the early Greeks and Romans were frequently strengthened by bands of iron which sometimes met at the prow and formed a ram. The Norse "Sea Kings" hung the shields of their soldiers along the sides of their galleys. Coming down to modern times, the floating batteries used by the Spanish when besieging Gibraltar in 1783, were protected by thick walls of timber strengthened by thicknesses of hide and bars of iron.

Fulton

In our own country, Robert Fulton, in the war of 1812, proposed to build an impregnable floating battery, propelled by steam, that would relieve the blockade at the mouth of the Delaware. Congress authorized him to begin the work, and he began the construction of a peculiar one with two hulls, between which the paddlewheel worked. The walls were made of wood, but of great thickness. The boat was not completed in time to take part in the military operations. Something like it was afterwards rebuilt and it is said to have been covered with thin plates of iron.

After the war of 1812 the development of home industries and internal improvements offered such a wide and profitable field to American ingenuity and industry that not much attention was paid to naval affairs. The United States seemed to be content with the building of wooden frigates similar to those that had distinguished themselves in single combat with vessels of a corresponding class of the British navy.

Stevens Family of Inventors

Fulton had as rivals, "foemen worthy of his steel," in the famous Stevens family, who were distinguished American engineers. In 1804, Colonel John Stevens fitted out a steamboat with a double screw. His propeller was a crude four-bladed one and the engines were not powerful enough to make it a success, but beyond the shadow of a doubt the modern screw propeller is its lineal descendent.

In 1812, Colonel Stevens planned a fort for the defense of New York, which was to be plated with iron and revolved by machinery, and the same year submitted a plan for a boat closely resembling the Monitor type, also to be armor clad. It is said that this was the first plan for a fully armored ship. About this time, Edwin A. Stevens, a son of Colonel John Stevens, was making experiments with a 6-pound cannon to determine the resisting power of iron plates.

First Ironclad

In 1841, the Stevens family submitted plans for a ship to be protected by 4 1/2 inches of iron, which their experiments had proven would resist the cannon of that day, and in 1842 Congress voted an appropriation Of $250,000 for the building of such a vessel by the Stevens Brothers. It was to be 410 feet long, 45 feet inside the armor, of light draft, 2 feet of freeboard and with a square, immovable turret. Through the fault of Congress it was never completed.

Ericsson improved over the Stevens' idea by combining the Stevens boat of light draft, low freeboard and armored sides, with the Timby revolving turret.

Forced Draft

The air-tight fire room devised by Edwin A. Stevens and patented April, 1842, marks another step in advance for our battleship, as it made possible "forced draft," by which air is forced into the furnaces by a powerful fan, blowing the fires like a blacksmith's bellows.

Revolving Turret

This period seems to have been a prolific one for military ideas and we find Theodore R. Timby, of Dutchess county, New York, presenting in 1841 a model of a metallic revolving tower. He filed his caveat with the patent office January 18, 1843, and the same year completed and exhibited an iron model, and a little later presented a model to the Emperor of China through the American representative, Caleb Cushing,

In 1848 a commission of Congress made a favorable report to the Secretary of War upon Timby's proposed svstem, and when the Civil War broke out he had patents for "a revolving metallic tower" and for a "floating battery to be propelled by steam." His claim was so good a one that when Ericsson began the construction of the "Monitor," a United States court granted Timby an injunction, restraining Ericsson from proceeding until he should have paid Timby a royalty for the use of his invention. Timby settled with Ericsson and his financial backers, Bushnell and Delamater, for $100,000. In 1862, Timby devised the method now used for firing heavy guns by electricity.

In 1843 John Ericsson made the "Princeton" for the United States. She was the first warship to be moved by the screw propeller, and her engines were below the water line. With the engines where they were not liable to injury by the artillery of the day, and a screw propeller out of harm's way beneath the water substituted for the fragile side paddle-wheel, the modern warship made quite an advance.

Armored Ships

In 1854 the French constructed three floating batteries with the speed of 4 knots an hour, armed with 68 pound guns and protected by iron plates. They were very successful in the Crimean war. In the same war the annihilation of the Turkish fleet in one hour by shells fired from Russian guns, demonstrated the absolute necessity of some protection. The Crimean war over, France at once proceeded to construct an iron-plated frigate. She took the "Gloire," a wooden two-decker, removed the upper deck and used the weight thus gained to carry 4 1/2 inch armor from end to end. She had no ram, but the iron plates made her bow strong. This ship was fitted with sail and steam power, and could make 13 knots an hour. Her appearance alarmed the English; they at once set to work, and in 1859 produced the "Warrior," made of iron and especially designed to carry armor. She was 420 feet long, and had a patch of plate 218 feet long, 4 1/2 inches thick over her battery and water line amidships. The same year the French laid down two more ironclad ships, the "Magenta" and the "Solferino," and fitted these with rams.

First English Turret Ship

In 1860 Captain Coles, of the English navy, submitted a plan for a ship to carry nine conical turrets, each to contain a pair of guns. The first English turret ship was the "Royal Sovereign," a three-decker cut down to Captain Coles' plan, plated on the water line and above with 4.1-inch iron, with 4 turrets, 10 inches thick in the exposed positions and 5 inches thick elsewhere. She was tried July, 1864, and accepted soon afterward.

American Ironclads

In 1861, Captain Eads, of St. Louis, made some Mississippi gunboats with curved decks and plated with thin iron. These were the first ironclads the United States used in warfare, and in the curved deck of Captain Eads we have the prototype of the protective deck of to-day.

Monitor

In 1862 appeared Ericsson's "Monitor," especially designed as a light-draft boat, fitted to navigate shallow harbors and rivers and to be impregnable to the fire of forts. Her length was 173 feet, beam 42 feet and 6 inches, side armor 5 inches, turret, 8 iron plates each 1 inch thick. The turret inside was 20 feet in diameter and 9 feet in height, and carried two 11-inch guns, firing with 15 pounds of powder a projectile weighing 166 pounds. The service charge was afterward increased to 45 pounds.

Had such a charge been used in her memorable battle at Hampton Roads, it is doubtful if the casemates of the "Virginia" would have withstood her attack.

How Warships are Classed

The boy who asked his father the difference between a battle-ship and a cruiser, and was answered that the battle-ship was one named after a State and the cruiser one named after a city, may have been satisfied for the moment, but his confidence in his father's infallibility will sometime receive a rude shock.

One may take up a newspaper and read that Congress has authorized the building of a ship of a definite displacement to carry as thick armor and as heavy guns as are practicable. The displacement alone, unless the cost be attached, is the only definite quantity named.

Displacement

Displacement is the weight of the ship complete, and is measured by the weight of water she displaces when afloat. It is not to be confused with tonnage, which means how much she can carry.

Usually the basis for the designer is the displacement, which may be likened to a bank account, in exchange for which he may have certain things whose total weight must not exceed his proposed displacement. These are the hull, engines, fittings, provisions, coal, stores, ammunition, armor, guns, etc. Their total weight, as we have seen, is limited, but in what proportion shall he dispose of them? That will depend upon the requirements of the kind of ship he is to build.

Class Requirements

If a cruiser to catch unarmed merchantmen, speed is the prime requisite. If a cruiser capable of overcoming other cruisers she is likely to meet, more allowance will be made for armor and guns. If a battleship, armor and guns will receive the first consideration. If a torpedo boat, to make its way unseen in a foggy night, the maximum speed and minimum size will be required. All these types make fairly distinct classes. Let us see what will be required of the cruiser.

Cruiser's Duties

1. To destroy commerce by capturing unarmed or lightly armed merchantmen and also by creating such terror that merchantmen will not dare put to sea when the cruiser is known to be abroad.

2. To protect commerce by " convoying " or accompanying as a guard, merchant fleets throuogh the dangerous parts of the route or from port to port.

3. To protect commerce by clearing the route from hostile cruisers.

4. To attack unprotected coasts or those but poorly fortified, and by their threatening presence compel the enemy to retain ships and men for defense that he would otherwise use in an attack elsewhere.

5. To carry on small wars at a distance where a powerful fleet is not needed, and to make reprisals.

6. To act as scouts, to be the "eyes of the fleet." It is important that they have great speed to do this, as after an enemy is sighted every hour of time or fraction thereof that may be given the opposing commander for preparation is valuable.

7. To keep up communication between a squadron and the base of supplies.

8. To form the front, rear, and wings of a fleet when in motion, and to be the first to discover the enemy.

9. To make blockades effective by being able to catch the fastest merchantmen. To be sure the monitor "Terror" did capture a prize off Havana, but it was because the prize was within range of the monitor's guns when discovered. A hunter doesn't take a bull dog to capture a fox.

Commerce Destroyer

Commerce Destroyer

Suppose we want a cruiser to act as a commerce destroyer; she must have speed enough to catch the fastest merchantmen afloat, and sufficient gun-power to overcome them when caught.

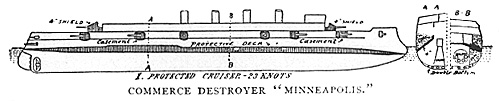

COMMERCE DESTROYER "MINNEAPOLIS" That she may have speed, the most powerful engines must be given her, and that she may keep at sea for a long time, large supplies of coal must be carried, while enough protection must be given to the "vital parts" of the cruiser to defend them from any guns the merchantman may carry.

Vitals

The parts that must be defended are the engines, the magazines and the steering gear; only less urgent is defense for the guns. How is it given? The " vitals " of the ship will be placed below the water-line because few projectiles except plunging-shot at close range will penetrate much below the water. The " vitals " will further be covered overhead by a "protective deck."

Protective Deck

This protective deck extending the whole length of the ship and from side to side much resembles a huge inverted platter. On the sides and ends it is below the waterline, but it slopes or curves upward from the sides, until over the middle part of the ship it is as high, or a little higher, than the water, and presents a flat, or nearly flat, surface, like the bottom of the platter. This deck is made of excellent steel, ranging in different ships from one to six inches in thickness. The slopes are thickest and are intended to present an inclined surface, from which shot and shell will glance without penetrating. Along the middle part of the ship, between the slopes and the outer wall, bunkers (coal bins) are arranged. These also assist in protection, for a foot of coal is equal to about one inch of wrought-iron, or half an inch of steel in this respect.

Next, the guns will need attention.

Gun Shields

The cruiser of this class will not mount many heavy guns. If 4-inch or 6-inch guns, they will be placed on the highest deck and protected by circular gun shields of steel armor attached to the gun carriage and revolving with it. The shield will probably be face- hardened steel about four inches in thickness, and will successfully resist common shell. If larger than 6-inch guns they will probably be placed within a turret.

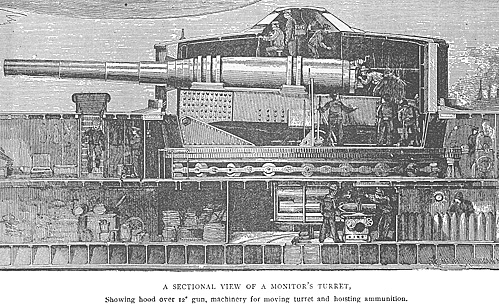

Turret

The turret is a circular steel tower, with openings through which guns project, and is made to turn by machinery in any desired direction. Only the heavy guns of the ship will be placed within turrets.

Along the sides of the ship (broadside) and projecting through portholes will be other guns, and the space in front of these will be protected by light armor.

Double Bottom

Having provided for defense against shot and shell, let us see what next will be required. The warship must stand attacks from three weapons, the gun, the ram and the torpedo. In cruising an unknown coast she may encounter reefs and shoals not down on her chart, or in the darkness of night may come in collision with another vessel. She will be protected in this respect by giving her a double bottom. The inner and the outer walls will be from one to three feet apart, and the space intervening divided into numerous little water-tight chambers. From the protective deck up as high as the water will reach she will probably have a cofferdam of cellulose, made from corn pith, which has the peculiar property of swelling rapidly when exposed to water, so any break in the wall, if not too large, would be speedily closed by the cellulose.

Beneath the protective deck there will be several partitions running across the ship (transverse bulkheads) and probably one or more partitions running the whole length of the ship (longitudinal bulkheads). These will divide the ship into numerous compartments, which can be closed by water-tight doors, and the ship might keep afloat indefinitely with two or perhaps more of the compartments flooded, if no damage were done to her engines. Her engines will be such as to give the greatest power with the least possible weight, the economy of fuel not counting for so much as in a ship used for purely commercial purposes. So powerful are the engines of the cruiser that they would drive the machinery to furnish the electrie light for five cities of 50,000 inhabitants each. Her enormous coal bunkers will hold hundreds of tons of coal that she may make long voyages without being compelled to put into port.

To recapitulate, then, our cruiser is protected against the ram and torpedo by her double bottom and belt of corn pith; her vitals covered by the protective deck and her broadside guns by armored casements; her guns on deck by gun shields and light-weight turrets. Any of this armor could be penetrated by the heaviest guns, and the commerce destroyer must be able to show a clean pair of heels to anything she cannot whip.

Armored Cruiser

Armored Cruiser

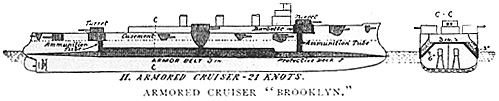

ARMORED CRUISER "BROOKLYN"

The armored cruiser must be able to brush away hostile commerce destroyers and leave the route clear for merchantmen. She will be a pretty formidable fighting machine, and might occupy a position in the reserve of a fleet next the fighting line. We shall expect to find in her, high speed, greater displacement, heavier guns and thicker armor than in the protected cruiser. The protective deck will be thicker; the armor on the gun positions heavier. In addition, she will have about her waterline a belt of armor, probably seven feet or seven and a half feet wide and from two to twelve inches thick. This may extend completely around her or along her side far enough to cover the most vital parts of the ship. About three feet of belt will be above the waterline. It is this belt that gives her the name " armored cruiser."

The ammunition hoists (elevators), passing from the magazines beneath the protective deck up to the turrets containing the guns, will be protected by an armored tube from three to ten inches in thickness. The great quantity of coal that her powerful engines require, and other considerations, will usually forbid her protecting the space between the turret and protective deck by armor, but the coal will be arranged along her sides so as to give some protection in itself. The cofferdam of cellulose, made from corn pith, or some similar substance, will be thicker, the hull heavier and stronger, with double bottom like the cruiser of the other class.

The "Brooklyn," a fine armored cruiser, is divided below the deck by twelve transverse and two longitudinal bulkheads, and above the deck by ten tranverse bulkheads, which are again subdivided into 140 compartments. None of the bulkheads on our cruisers are armored. The cofferdam along the side above the armored deck is filled with cellulose up to the level of the gun deck.

Sponsons

Our armored cruiser will mount some pretty heavy guns. In the United States navy for vessels of this class they are 8 inches; in the Spanish 11.2 inches. Some of her broadside guns will be placed in an armored projection resembling a bay window, called a "sponson," which will enable them to be pointed directly ahead or astern, and thus increase materially their area of fire.

Recessed Ports

Guns in the bow of the ship may look out of ports which have been notched, depressed, or cut in to allow the gun to be trained directly ahead. An arrangement somewhat similar is sometimes made along the side to give greater freedom of motion to the gun, and ports of this character are said to be " recessed."

Our armored cruiser will have speed sufficient to catch anything but the very fleetest commerce destroyers. and coal endurance sufficient to make long voyages from home. Cruisers have a high freeboard, that is, they stand well out of the water, mounting their guns twenty feet or more above the waterline, which enables them to be used in rough weather. In this respect they possess a marked advantage over a monitor and the coast defense battleship, whose guns might sometimes be almost under water, or their muzzles so far depressed that if fired their projectiles would strike the tops of the waves between them and their target.

Conning Tower

Back of the forward turret, and high enough above the deck to give a good view, will be the "conning tower," an armored steel tower pierced by narrow slits through which the commandino- officer will watch the progress of the battle and direct the movements of his vessel. This tower will be connected by electric bells, speaking tubes and telephones with every portion of the ship with which the captain will need to communicate. The conning tower should be strong enough to resist the ordinary fire to which it is likely to be subjected, and the electric wires communicating with it usually run through an armored tube until they pass beneath the protective deck. Above the conning tower will usually be found a rather frail structure, not built to resist shot and shell, called the "chart house," from which the ship will be navigated except in battle.

Military Masts and Fighting Tops

Cruisers of this class usually carry what are known as "military masts." These are not intended for the use of sails, but are hollow, tapering, steel structures, about which are built one or more platforms or balconies, where riflemen and machine guns will be placed. The fire from these will be expected to sweep off the men from the exposed positions of the hostile ships. Our cruiser will also be furnished with powerful electric searchlights, perhaps of 100,000 candle power, which may be turned so as to throw their rays in any direction. The electric light and the small rapid-firing gun are the warship's defense against her small but terrible enemy, the torpedo boat.

The armored cruiser will not be expected to engage the battleship unless the conditions are such as to give her some advantage to make up for her lighter guns and thinner armor. If the battleship had been injured so that she could not fire all her guns, or if water had entered some of her compartments and thrown her off an even keel, so that but few of her guns could be pointed in some particular direction, the cruiser might take this position, and by means of her superior speed remain where, without great damage to herself, she could pour in a destructive fire upon the disabled battleship. In general, however, she will trust to her speed to protect her from anything she cannot whip.

Battleships

Battleships

BATTLESHIP "OREGON."

Admiral Colomb of England says: "The battleship is a representative of the force waiting to be attacked and daring attack. If there is ever to come anything which is stronger, offensive and defensive, than the battleship, she must disappear, for the theory on which she rests is that there is nothing but another battleship which is capable of offering her any fair match. She has always to secure herself against special attack. The other day it was the unarmored gun vessel which threatened her; she met it by adding her medium battery; later she was to be swept off the seas by a swarm of torpedo boats; she met it by adding the machine gun battery; at the present moment it is suggested that rams, pure and simple, small and swift, will be too much for her; she looks calmly down and would like to see them try.

All such threats annoy her, but she sees clearly that whatever beats her must take her place. No special rams, no special torpedo boats can take up and hold her defensive position. If they cause her to disappear they must follow, because it is only her existence which justifies theirs. I believe firmly that the battleship, as a battleship, will hold her own to the end of time."

Requirements

Since the battleship is built to fight and not to run, we shall expect to find in her the most powerful guns and the strongest armor consistent with her displacement and seagoing requirements. The United States is building two distinct types of battleships; one, of the Indiana class, with the low freeboard, called a coast defense battleship; the other, like the Iowa, with a higher freeboard, called the seagoing battleship. She will be given displacement somewhat larger than the armored cruiser, the hull will be stronger, perhaps with a triple bottom reaching up to and forming a shelf on which her armor belt rests, and divided into numerous water-tight chambers.

She will have a heavy protective deck, an armor belt from seven feet to eight feet in width and from eight inches to eighteen inches in thickness. Above the protective deck transverse armored bulkheads will be built fore and aft to stop the enemy's shells which come in at the stern and bow. Along the sides, above the armor belt connecting the bulkheads, armor will be placed sufficient to keep out medium gun fire, that is, common shells and projectiles from guns six inches and smaller.

The latest five and six-inch guns have shown on the proving ground their ability to pierce armor thicker than that usually carried to protect the secondary battery of our battleships, but in actual battle, with the gun and target each in motion and the armor inclined at an angle to the projectile, normal hits are likely to be few. Then the armor piercing shell, because of its thick wall, cannot carry so large a bursting charge as the common shell, so its effect within the ship would not be so terrible as that of the other.

Redoubt

Since this armor must be so heavy (perhaps one-third of the entire displacement of the ship is given to it), it will be impossible to completely cover the ship with it, and so we shall find it in the form of a huge steel box (redoubt) extending far enough ahead and astern to include within its walls the machinery moving the turrets, the ammunition hoists and the most important parts of the ship above the armored deck.

It is expected that considerable portions of the bow and stern above the protective deck -might and probably will be shot away in action, but unless our constructors are wrong in their calculations, this might be done and the battleship still be able to maintain a most formidable resistance. The destruction of the unarmored bow may impede the speed of the ship and cause her to steer badly, and water coming in here or at the stern may put the battleship on an uneven keel, perhaps to such an extent that she might be troubled to bring her guns to bear on an enemy.

In such positions she would present an inviting target for the attack of the torpedo boat or the ram.

Primary and Secondary Battery

The batteries of our battleship are known as primary and secondary. In the primary battery are the large guns from 8-inch to 13-inch with which she will attack the thick armor of her opponents over the vitals and the opposing heavy guns. The primary battery should be supplemented by smaller rapid-fire guns from 4-inch to 6-inch and with these she will attack the unarmored or thinly armed portions of the opposing ship and the portholes through which the heavy guns look out.

The secondary battery will be made up of smaller rapid-fire guns, such as Maxim, Nordenfeldt, Hotchkiss, Driggs-Schroeder or Gatling, whose projectiles range in size from that of a rifle ball Up to a 12-pounder and fire from 30 times for the latter to 800 or 1,000 times for the small machine guns. With these she will sweep away all men from the exposed positions on the hostile deck and defend herself when attacked by the torpedo boat.

Barbette and Turret

These in the battleship must be far more powerful than in the cruiser.

The barbette is a steel tower intended to protect the heavy rollers on which the base of the turret rests, the machinery for turning it, the guns within the turret and all the machinery connected with them. The guns look out over the top of it and usually in a battleship it extends continuously down to the protective deck. Within this like a smaller tube within a larger one in a spy-glass is placed the turret, mounted on heavy rollers with suitable machinery for turning it and pierced with port-holes through which guns project.

The barbettes show very plainly in the pictures of the monitor " Monterey " and the battleship " Maine," and look like large hoops encircling the turrets at the base.

The Modern Warship

Our warships are now propelled by engines of over 20,000 horse-power, and in addition have numerous auxiliary engines for heating, lighting, ventilating and working different parts of the ships. The " Columbia " has ninety-four engines and pumps. The boilers of the " Iowa " present more than an acre of heating surface. The " Indiana," if used as a ram at full speed, would strike with force sufficient to lift 100,000 tons one foot. One filling of the ammunition magazines of the " Kearsarge " cost $383,197.

The report of the chief of the bureau of equipment shows that last year the cruiser " New York " used her coal as follows: For moving the ship, 2,090 tons; for distilling water for her engines and crew, 831 tons; for running her pumps, 1,049 tong; for lighting the ship, 1,431 tons; heating, 453 tons; cooking, 88 tons; steam launches, 123 tons, and ventilating, 1,064 tons.

Apportionment of Weight

In the construction of a battleship of 11,290 tons, 4,540 tons will be given up to the hull; 3,630 to armor, protective deck and cofferdam; 1,000 tons to her guns and ammunition; 1,170 tons to her machinery, stores, etc.; 625 tons for her coal; 325 tons allowed for her crew equipment and outfit, and the whole complete will cost $5,000,000.

The battleship of to-day represents a compromise of the ideas of numerous designers. Ever since the use of the explosive shell there has been a steady fight between the armor and the gun, first one ahead and then the other. In the beginning it was possible to cover the whole ship with armor, but to-day, when a 13-inch gun will penetrate 22 inches of steel at one mile, only the most vital parts of the ship can be covered, leaving the ends exposed. Some critics contend that with the bow or stern shot away so much water would be let in that the vessel would be almost unmanageable, or perhaps in the case of one like the "Indiana," whose center of gravity was high, would even capsize. Nevertheless, the battleship has the confidence of her designers.

Admiral Sampson, in North American Review, says of her: "She mounts heavy guns to pierce the armor of her enemies; she mounts numerous guns of lighter calibre to enable her to meet similar fire from all sorts of craft and to destroy the quick-moving torpedo boats, which would escape the slow-working heavy guns. She carries armor to protect herself against any but the heaviest projectiles, and, so far as possible, against even these. She carries torpedoes to destroy an enemy who may, in the manoeuvres of battle, come within her reach. She carries such a supply of coal and ammunition as will enable her to perform her duty between the times when she can renew her supply. Being essentially a fighting machine, she does not require high speed to enable her to escape from an enemy. When war shall come between any of the great nations which depend in whole or in part upon their naval strength, it will be the battleship which will settle the issue."

The behavior of his ships at Santiago shows that his confidence was well placed.

Monitor

The name of the first of a series of boats of peculiar construction built by Ericsson has come to designate a type. The characteristics of the monitor are its low freeboard, thick armor and armament of a few heavy guns. Their engines are comparatively light, and the "Monterey," the fastest in the United States service, has a record of only 13.6 knots under the most favorable circumstances.

Cause of Popularity

The theatrical appearance of the first monitor, and its excellent service at a critical moment, seem to have given it a somewhat higher value in the eyes of most Americans than its abilities will justify. It is a most useful vessel within its sphere, but that sphere is limited.

Secretary Long says in his report: "There is no advantage to be gained by building ships of this description. Such a vessel cannot attain to high speed. It can neither overtake nor escape from a battleship. Its comparative smallness of target, usually mentioned as one of its chief advantages, is apparent rather than real, for that feature of the battleship which changes the size of the target, although vulnerable, is not indispensable to the safety or fighting efficiency of the vessel. The chief defect to be found is the serious disadvantage under which guns are fought in any but the smoothest water."

Duties

A boat of this class lies low in the water, is light of draft and not fitted for work in heavy seas. As harbor defense boats they can render excellent service, their light draft permitting them to move about in the water where an opposing, heavy draft battleship could not follow, and thus choose their own ground and distance at which they fight. If the monitor elected to fight the battleship at long range, as she perhaps would, the small target she presents and her heavy guns would be decidedly in her favor, as the battleship could get but little good out of its secondary battery of rapid-firers if fighting at more than 2,500 yards. The low speed of the monitor gives any other ship the option of accepting or declining battle with it. It can only fight when the "other fellow" is willing.

Construction

The monitors of the United States range in length from 200 feet in the "Jason," "Nahant" and "Lehigh" class, to 259 feet 4 inches forthe " Terror " class, and 289 feet for our largest one, the "Puritan." Beam, 46 feet, 5 5 feet 9 inches, and 6o feet i IF inches; draft, 11 feet 6 inches, 14 feet 7 inches, and 18 feet 1 inch, respectively, for the classes named.

The bottom will be double, with numerous water-tight chambers coming up to within 3 feet of the waterline, where it forms a shelf on which an armor-belt of from 5 inches to 13 inches in thickness and 7 feet in width rests. A protective deck from 2 to 3 inches in thickness heads the armor-belt at the top.

The barbettes and turrets of the later monitors will be from 9 inches to 14 inches, and the conning tower 8 inches to 10 inches in thickness, of good Harveyized steel. Originally the monitors were planned to carry four heavy guns. The rise of the torpedo-boat has compelled them to strengthen the superstructure and mount some rapid-fire guns. Of course, guns in this position are as much exposed on the monitor as on any type of ship.

Turrets

Turrets

The tops of the turrets of monitors, 11 inch steel, expose a vulnerable point to a plunging fire. This would render them unsuited to attack land batteries at high elevation.

Within each turret are placed two heavy guns, with a peculiarly effective device for "training." Between the guns, and looking through slits, in a projection in the top of the turret, called "sighting-hood," stands the operator whose duty it is to aim the guns. In front of him, and looking through two small openings, are two crossline, telescopic sights. By turning a small hand wheel he moves these sights to the right or left until they bear on the target. Another wheel depresses or elevates them. These sights, by a refinement of mechanism, are made to correspond with the guns, and so when the telescopic sight in the sighting-hood points directly at the target the corresponding gun in the turret is properly aimed.

Electricity, steam, or hydraulic power supply the force required to move the guns and the machinery of the turret. In the early monitors the turret revolved upon a spindle, but in our later ones the spindle has been discarded for heavy rollers on the decks.

Torpedo Boats

The torpedo boat seems to have made its first successful appearance during our late Civil War. It was then a very crude affair. R. 0. Crowley, electrician for the Confederate States, has told of some of the difficulties under which they labored, and their results. One of their most successful trials was the attempt to blow up the United States ship " Minnesota." With a small launch fitted with a long spar at her bow, to which was attached the torpedo arranged to explode upon contact, they steamed, in the darkness of the night, through the blockading fleet without their identity being discovered, although frequently challenged by lookouts. The "Minnesota" was found, the torpedo was lowered, the spar run out, and a dash made for her side. Although the torpedo was loaded only with gunpowder, the explosion was terrific, and resulted in such severe damage to the "Minnesota" that she was compelled to be docked. The torpedo boat escaped in safety.

Cushing

It was in a similar boat, and with a spar torpedo, that Lieutenant Cushing, of the United States Navy, made his successful attack upon the ironclad "Albemarle."

"Cigar Boat"

One of the most heroic achievements of any navy was that of the "cigar boat," constructed at Mobile, Ala., and sent by rail to Charleston in the summer of 1863, It was made of boiler iron, was about 30 feet long, 4 feet wide, and 9 feet in depth. The interior was reached by two manholes, in the tops of which were glass bull's-eyes, through which the navigator looked when directing his craft. It was moved by a screw propeller, and the power furnished by a crank turned by the crew. Along the sides were wings which could be adjusted at an angle. When the front of the wings were inclined downward and the screw turned the boat would dive; upon their being reversed it would come to the surface. Ordinarily it floated with only the manholes a little above the water. It seems to have been the prototype of the "Holland Boat." A tube of mercury served to mark its depth in the water.

It was intended that this boat should pass under the vessel attacked, towing in its wake a torpedo which would be exploded by contact or electricity when the torpedo touched the vessel. There was not sufficient water in Charleston harbor to allow this, and the boat was rigged with a spar torpedo. Thrice she sunk in her trials with the loss of all on board, but although service in her seemed certain death, there never was any difficulty in securing a new crew for her.

After thirty men had lost their lives on board her, Lieutenant Geo. E. Dixon of Alabama secured as a volunteer crew Captain J. F. Carlson of the army, Arnold Becker, C. Simpkins, Jas. A. Wicks, F. Collins, - Ridgeway and directed a final attack against the United States ship "Housatonic," which was reported the next morring to have been sunk by a torpedo, and nothing was heard of an attacking boat. Long afterward, when the. Government attempted to raise the " Housatonic," the little "cigar boat," with its gallant crew, was found not far from her victim.

The history of the spar torpedo in America may be summed up as follows: United States ship " New Ironsides" seriously injured off Charleston, October, 1863; sloop-of-war "Housatonic" destroyed off Charleston, February, 1864; monitor "Osage" destroyed by drifting torpedo, March, 1865 ; the Confederate ironclad "Albemarle" destroyed October 27, 1864. All of the torpedoes were charged with common black powder.

The brilliant achievements of the torpedo boat in the Civil War inclined the navies of Europe to look upon it with favor, and they soon began to make experiments. The weapon used at that time was, as we have seen, the spar torpedo, and this meant that it was necessary to come alongside and in contact with the enemy before the boat was discovered and disabled.

Small rapid-fire guns and modern searchlights were not then in use, and the boat in the hands of fearless men on a dark or foggy night was a dreaded and dangerous enemy.

Late in the '60's the " Whitehead " torpedo was introduced, and in the early '70o's European nations took it up and began the construction of boats especially designed to carry it. The first were then about 57 feet long, 71 feet wide, with go horse-power engines, giving a speed of 16 knots. To-day they are from i00 feet to 200 feet long, 12 feet to 20feet wide, and driven by 6,000 horsepower engines, giving them a speed of 30 knots and upward, and fitted with a "Whitehead" or some similar automobile torpedo supposed to have an effective range up to 800 yards.

There is no well marked line dividing the coast defense torpedo boat from the sea-going torpedo boat and the latter from the torpedo boat destroyer. The safety of the boat depends upon its small size and extreme speed. If the size is increased to give more speed and sea-going qualities, it defeats the very object for which it was originally intended; i. e., a boat small enough to approach the enemy under cover of fog, smoke or darkness without being discovered and disabled before it is within effective range of its torpedo.

The old boats were fitted with three torpedo tubes, two on deck and one in the bow. The bow tube is now discontinued, as the boat under motion throws up a big bow wave that interferes with the accurate firing of the bow tube, and further, before the torpedo can gain head, way, the boat, at a high rate of speed, is likely to run it down. The torpedo boat will also mount machine guns and light rapid-fire guns, and the torpedo boat destroyer, rather heavier rapid-fire guns, 6-pounders and 12 pounders, to enable them to destroy the torpedo boat.

Duties of the Torpedo Boat

It is intended that a boat costing a few thousand dollars, and manned by a score of men, will attempt to destroy the expensive cruiser or warship costing millions. If discovered, her fate is almost certain; it is upon secrecy that her success depends. She relies upon her small size, her color as nearly resembling her surroundings as possible, fog, smoke or darkness. The torpedo boat must also act as the protector of the fleet from hostile torpedo boats. To destroy these she must discover them, and to discover them it is necessary that the size and surface of the 'guarding boat should not be so plainly visible to the attacking boats that they will make her out in time to avoid her. The modern torpedo boat destroyer with its large size (400 tons) may, under ordinary circumstances, defeat its own purpose.

Rough Water

The extreme speed of the torpedo boat is made in still water; with its small tonnage and light draft the speed materially decreases in rough water, while in a heavy sea-way they would fall an easy prey to a fast cruiser.

Sailors taken from their pleasant quarters in larger vessels find the change to the torpedo boat irksome, and many stories are afloat as to the danger of such service even in times of peace. It will be interesting to note that Massachusetts has annually 40,000 of her sailor population who earn a livelihood in fishing boats of an average of 50-tons displacement.

Torpedo Boat in Action

No vessel has yet, when in motion on the open sea, been destroyed by the "Whitehead" torpedo.

If a torpedo boat headed directly for her enemy was discovered at 2,400 yards, it would be necessary for her to get within 500 yards or 600 yards before she could use her torpedo. Even at a high rate of speed she would thus be exposed to the fire of 6-pounders, 12-pounders and large rapid-fire guns for at least three minutes. A 12pounder in that time would easily discharge from 20 to 30 aimed shots, one of which, well placed, would disable the approaching boat. The larger rapid-fire guns, sixinch, could discharge in that time 15 to 20 aimed shots, any one of which would, perhaps, be effective.

The Japanese, when tired after a battle, with ammunition low, dared not risk a night action with a fleet when Chinese torpedo boats were known to be in the vicinity. The Chinese boats at the battle of the Yalu did no effective work. In theory they should have dashed into the battle under cover of the smoke and wrought their enemies great damage. One tried and its engines went wrong. Another one fired three times at close quarters and missed each time.

Torpedoes can do little against battleships while their secondary battery is in good shape. Three attacked the "Olympia" at Manilla; one was quickly sunk, one retired, and the third was beached to prevent sinking.

The torpedo boat's time will come at the close of the battle, when the ships are partially disabled, the crews tired, the smoke hanging over the scene, and the rapid-fire battery dismounted or silenced, then after a ship is disabled, perhaps on uneven keel, she will fall an easy prey to the torpedo boat.

The moral effect of the torpedo boat will have a very real influence upon warfare. The constant strain upon the nerves in keeping a lookout will wear upon a fleet, and the danger that a floating fortress costing millions of dollars will be destroyed by the insignificant yet terrible little enemy will make nations careful about building larger and more expensive warships. The knowledge that a harbor is defended by such a fleet will tend to keep an attacking squadron at a distance at least a portion of the time.

All in all, the very fear that torpedo boats incite will well repay their construction, if they render no further service. Even so high an authority and staunch an adherent of the battleship as Admiral Colomb, of England, is beginning to look with favor on boats of the " destroyer " class.

- She's a floating boiler crammed with fire and steam,

A dainty toy, with works just like a watch

A weaving, working basketful of tricks -

A pent volcano and stoppered at top notch.

She is Death and swift Destruction in a case

(Not the Unseen, but the Awful -plain in sight).

The Dread that must be halted when afar ;

She's a concentrated, fragile form of Might

She's a daring, vicious thing

With a rending deadly sting

And she asks no odds nor quarter in the fight

- (James Barnes in "McClure's" for June,

1898)

The Automobile Torpedo in Battle

Previous to this quarter century the only torpedoes used in action were either of the towing or spar variety. The development of the electric searchlight and rapidfire gun rendered these varieties obsolete, and inventive talent began to turn itself to a torpedo that could be used at longer range.

"Whitehead"

The " Whitehead " torpedo, now most generally used, appeared in crude form in 1868. It is a long, fish-shaped shell, with three compartments. The first chamber contains the explosive charge, the second chamber the compressed air cylinder furnishing the motive power, and the third chamber the machinery for turning the screw propeller at the stern. The torpedoes of to-day are from fourteen to eighteen inches in diameter, from eleven to eighteen feet long, carry from 120 to 2 20 pounds of guncotton, and can run about 800, yards, the greater part of the distance at a thirty-knot rate.

Warhead

The front chamber of the torpedo, called the " warhead," is detachable, and contains the wet gun-cotton for the charge and the machinery necessary to explode it. The warhead is kept in the ammunition magazine and attached to the torpedo the last thing before entering action. Wet gun-cotton is used because it is one of the safest of the high explosives. As one writer has expressed it, "Wet gun-cotton may be safely chopped up with an axe." It can only be exploded by the concussion of another explosive. The fulminate fuse igniting a small quantity of dry gun-cotton is usually used to ignite the charge.

It is said that in the fight at Cardenas a projectile struck a torpedo of the boat "Winslow" and actually passed through the gun-cotton. Authorities claim the shell must strike the detonating cap to cause an explosion.

Discharging Torpedo

The torpedo is thrown from the tube by a light charge of powder, and on its passage the machinery within it is set in motion and it at once begins to propel itself, which gives it the name "automobile." If fired directly ahead, care must be taken that the boat does not overrun it before the torpedo has gathered headway of its own. Much skill is required in the use of the torpedo. If fired at a target which is in motion, allowance must be made for the position of the target by the time the torpedo can reach it. If fired from the broadside of a torpedo boat, allowance must be made for the "acquired motion" of the boat. In practice, dummy torpedoes fired from submerged broadside tubes have sometimes been brken in two as they entered the water, or even become entangled in the screw propeller of the boat. Such an event would be highly disastrous in action. A warship of considerable size at fifteen knots would have surrounding it a body of water in motion of considerable strength. Some authorities say this would afford protection from the torpedo.

The modern torpedo is a very complicated piece of machinery, and costs the Government, complete, $3,500, It possesses a contrivance by which it can be floated at any required depth so that it will strike beneath the armor belt.

"Howell"

The "Howell" torpedo is the invention of an American officer, and differs from the "Whitehead" chiefly in having within it a large balance-wheel, in place of the compressed air motor, which, before launching, is spun up to a high speed, and by its momentum after it is launched continues to drive the screw propeller.

Ram

"There are many who are in love with I the small swift ram,' but it is doubtful how far such a ship is attainable, and how far she would be useful if the ideal could be obtained. Ability to ram depends upon speed and handiness in the assailant and the want of these qualities in the assailed. To obtain a high speed, not only upon the measured mile, but at sea, the boilers must be heavy and the engines powerful. This necessarily involves a high displacement, as the hull must be strong to withstand the jar of the machinery and the violent concussion of ramming. If the ram is given guns and armor she becomes a battleship; if she is left without them she is liable to be destroyed by gun-fire long before she can use her sole weapon; and that weapon is a most uncertain and two- edged one. (Wilson's " Ironclads in Action.")

Early Use

The ram was a well-known and effective weapon of ancient naval warfare. Even in the days when galleys were propelled by rows of slaves chained to the bench it was often used with decisive results. The ram of the Greek vessel is said to have won the day for them in that all-important naval battle with Xerxes' fleet at Salamis. Two thousand years afterward the allied Christian fleet used it with equal effect against their Turkish enemies at the battle of Lepanto.

With the development of sail power and the decline of the galley, new methods of warfare found but little use for the ram. The sea breeze could not always be commanded, and the low- powered, crushing, splintering projectile took its place. The application of steam again gave a motive power that could be controlled, and the ram once more came into prominence.

First Appearanee in Modern Times

March 8, 1862, a Federal fleet of wooden sailing vessels lay at anchor' in Hampton Roads. About mid-day the lookouts reported the approach of a low, black, unsightly craft, the long-looked-for "Merrimac." Grim and ugly as death she steamed down the river directly toward the frigate "Congress" and the sloop-of-war "Cumberland." Although combined the two mounted 74 guns, the shot fell harmlessly on her sloping deck, although through one open port she received some damage, the muzzle being knocked off two guns and 19 men killed or wounded. But the fire from her guns crashed through the thin walls of the wooden ship with terrible effect. Selecting the "Cumberland," she steamed directly at her helpless victim and struck her fairly amidships, backed off and rained in a destructive fire of shot. The latter was needless; the "Cumberland's" fate was already decided, for a hole in her side was made big enough for a man to enter. Dramatic and terrible, the ram issued from the obscurity of the past and made its appearance in modern warfare.

After the action at Hampton Roads numerous rams were constructed by either side, and clever, light draft craft proved themselves of considerable value, especially' in defending narrow river channels where the heavier ships had little room for maneuvres.

Battle of Lissa, 1876

The ram was again used at Lissa in the battle between' the Austrian and Italian fleets. The Italians had a large fleet of good vessels, but their admiral, Persano, had little ability and less courage. At last, in obedience to repeated demands made upon him by his government, he set out across the Adriatic to attack the little Austrian town of Lissa. He did this, although there was an Austrian " fleet in being " commanded by Admiral Tegetthoff.

The Italian ships were far superior to the Austrian; individually the men were as brave, but their admiral, Persano, was unfit for the command, and Tegetthoff was an able and energetic officer of long experience. When the Austrian fleet appeared in sight that of Italy was split up into numerous little groups separated by miles. Persano attempted to get them into some kind of order, but as often as they would approach anything like a formation be would change his mind and signal for something different. At the last moment he left his flagship and went on board a ram, and during the action half his commanders had no knowledge of his whereabouts. The Austrian ships were painted black; the Italian, gray, and Tegetthoff gave the laconic signal "ram everything gray."

In his flagshig the " Ferdinand Maximilian " he struck the "Re d'Italian," and almost rammed her through. The Italian ship sank at once, her men cheering as they went down. Tegetthoff afterwards said: "If I were to live a thousand years I would never ram another ship. You see the vessel attacked at one moment, and the next 800 men sliding into the sea with a vessel following them."

Another attack by the Austrian "Kaiser," a wooden ship was not so successful. She received a broadside at close range and was set on fire, and suffered a great loss in men. Persano, on board the Italian ram, distinguished himself by refusing to use his vessel whenever an opportunity offered. Under the able leadership of Tegetthoff the Austrians won a substantial victory.

An English authority who has made an exhaustive study of the history of the ram, assures us that there is only one case on record in which serious damage has been inflicted by the ram on any ship under steam with sea-room.

If battles are to be fought at long range and smokeless powder used, the ram will be exposed for some minutes to a severe fire and when within torpedo range it is liable to attack from torpedoes as well as guns, as all the battleships are fitted with torpedo tubes.

"If the fleets charge one another end-on, there may be cases when the ram will be used, but there will be great danger then of end-to-end collisions should the commanders on each side be determined, and these will almost certainly result in the loss of both ships, unless, indeed, the bows of the ship on one side are so weak as to take the full force of the collision and to break it, More probably the less determined man will swerve at the last minute and expose his side, as did Buchanan at Mobile." (Wilson's "Ironclads in Action")

What a Naval Battle is Like

"The battleship has to carry about with her all sorts of odds and ends which arc essential to her in peace but useless in war. When the ship clears for action the boats cannot be taken below and must remain above to be shot to splinters and cause fire. Equally dangerous and difficult to dispose of are wooden companion ladders, mess tables, benches and the various impedimentia usually found between decks. If of wood, these will add to the risk of fire, which is very great. With the ship's upper deck thoroughly cleared of wood, there will be no wreckage to float and save the drowning, nor will the boats be of much use for saving life after a battle.

The ships will begin their action at about 2,500 or 3,000 yards. Upon the upper works of the ship will fall most of the damage inflicted during the preliminary cannonade. They will have been prepared for the strain in every conceivable way. Round the funnels sacks of coal will be placed, and near the quick-firers, mantlets to catch splinters. The conning-tower and the positions from which the ships will be fought will also, doubtless, receive attention. In this way the injury done may be reduced to a minimum, but it will still be extensive.

The effect of even small shells charged with high explosives upon unarmored structures is very deadly. Great holes will be torn in the outer plating; splinters and fragments of side and shell sent flying through the confined space within; and any wood that maybe about, which has not been thoroughly drenched with water, will be set on fire. The funnels and ventilators may be riddled till they come down, and inside them, on the splinter-gratings, which commonly cross them at the level of the armordeck, fragments of iron and wood will collect and obstruct the draft. If the ventilators are blocked, and the flow of air to the stoke-bold checked, the stokers and engineroom men will be exposed to terrible hardships--gasping in a hot and vitiated atmosphere for the air which cannot reach them. The boiler-force will fall and the steampressure sink. It is true that nothing of this kind appears to have happened at the Yalu, but the fire maintained there was not so accurate as it would probably be with highly-skilled and cool Western gunners.

"At the close of the long range cannonade will come the close action. The range will be diminished to 600 yards or 700 yards, and the stroncyer side will steam in to assure its victory. This will be the most terrible period of the action. Up to that time, indeed, the damage done to the vitals of the battleships will not have been serious, but no doubt the internal economy of these vessels will have been impaired. The heavy quick-firers, judging from the Yalu, will not, at long range, inflict much injury on the water-line. It will be upon the upper works, superstructures, military masts, funnels, ventilators, chart-houses, bridges and stacks of boats and top-hamper, that the hail of projectiles whether fired direct or ricochetting from the water, will descend." (Wilson's " Ironclads In Action")

Under cover of the smoke or taking advantage of deranged steering-gear or silenced rapid-fire batteries, the cruel ram and the deadly torpedo boat will approach to administer the finishing blow to a partially disabled antagonist. The nervous strain on the officers and crew at this period of the battle will be something terrible.

Definition of Terms

Arc of fire That part of a circle through which a gun can be moved and fired. It is least in a broadside and greatest in a turret.

Armor-clad A ship carrying vertical armor, that is, a belt, and on gun positions.

Axial fire Fire straight ahead or astern, parallel to the ship's keel. Guns in the French navy are arranged to give powerful fire of this character. Strong bow fire is necessary to meet torpedo attacks and when in pursuit of an enemy. Strong stern fire is necessary in a ship fleet enough to fight by drawing her enemies after her.

Barbette An armored tower inside which the guns are revolved. The guns fire over the top of the armor, and not through portholes, as in turrets. On our best battleships the barbette descends from the turret to the protective deck.

Belt The strip of vertical armor along the side of a ship, protecting the vitals from gun fire and the ram.

Boilers, water-tube and tubular In the first the water is carried in small tubes around which the fire passes; in the second the fire passes through tubes around which the water is placed.

Broadside fire Fire from the guns placed along the side of a ship or in turrets that can be turned to fire over the ship's side.

Bunkers The bins in which the ship carries her coal. When full they also serve for protection.

Casemate The armored position in which a gun is placed.

Coal endurance The distance a ship can steam at moderate speed without recoaling.

Commerce destroyer A ship especially fitted to prey on the enemy's commerce.

Compound engines Having two cylinders, one larger than the other. Steam is used at high pressure in the small cylinder, at a lower pressure in the larger cylinder. Triple expansion engines have three cylinders; quadruple expansion engines four cylinders.

Cordite A kind of smokeless powder used in English service.

Dry dock A dock into which a ship can be floated, the entrance closed, and the water pumped out, that workmen may get at any part of the ship.

"Fleet in being" A fleet free to move and threaten any point it, chooses. It is like a strong body of cavalry on an enemy's flank, threatening his communications with a base of supplies.

Floating batteries Guns mounted on platforms or in ships not designed for speed, but to be anchored in front of some exposed position. The French floating batteries at Kimborn in the Crimean war were the first armored ships used in modern warfare.

Forced draft Air driven into the furnaces by a pow- erful fan. It is a severe strain on the boilers, as it throws a current of cold air directly on the tubes and is likely to cause them to leak. When forced draft is used the air-tight doors of the fire rooms must be closed, and the atmospheric pressure in the room is increased.

Freeboard That part of the ship extending above the waterline. It must be high in a ship designed for service in all kinds of weather. Guns mounted on a high freeboard have an advantage in rough weather over others.

High explosives Explosives more powerful than gunpowder, as dynamite, melinite, cordite. These are used as bursting charges for armor-piercing shells.

Homogeneous fleet Ships closely resembling each other in armor, guns and speed. Such a fleet is strong, and possesses a marked advantage in action over one in which the individual ships differ greatly from each other.

"Jeune Ecole" The believers in the doctrine of Admiral Eube, of France, that the torpedo-boat and the cruiser have taken the place of the battleship, and that speed is everything. They attach much importance to commerce- destroyers and bombardments.

Knot In the ordinary acceptance of the term, means a nautical mile, equal to 6,086.7 feet. Knots may be reduced to their approximate equivalent in statute miles by multiplying by 1.15. Statute miles may be reduced to their approximate equivalent in knots by multiplying by .87.

Light draft Floating in but little water.

The log-line Ordinarily a small line attached to a kite-shaped piece of board, weighted at one end so as to stand upright in the water and remain stationary when thrown overboard from a vessel in motion. Knots are tied in the line at intervals of the 1/20th part of a nautical mile, and the number of these that runs through a man's fingers in half a minute shows the rate of speed of the vessel for an hour. There are now many kinds of patent logs which give the rate of speed with more or less accuracy.

Melinite An explosive made from picric acid, used as a bursting charge in shells. On exploding it generates suffocating gases.

Nickel steel An alloy of steel and nickel which gives great hardness and power to break up projectiles fired against it.

Palliser shell A steel shell with a chilled point.

Personnel The body of persons making up the naval force; used frequently with reference to their character. In distinction from material, meaning munitions of war, baggage, provisions, etc.

Plunging fire Fire from guns used in forts placed at a considerable elevation. Plunging fire is dangerous to the "protective deck."

Recessed ports A port in which the sides are cut at angle, or a portion of the side cut away to give greater freedom of movement of the gun.

Scouts Light, fast ships, whose duties are to discover the enemy and report.

Next: Chapter 9: The Spanish Navy 1898

Back to The Passing of Spain Table of Contents

Back to Spanish-American War Book List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com