A pause of three days occurred after Moore's footsore

soldiers limped into Corunna. The British transports had

not made their appearance, and had to be summoned from

Vigo. Soult's troops were almost as much exhausted as the

British, and it was not until the 14th that there were any

signs of the French onfall. Moore filled up the interval with

some grim preparations for embarkation. More than 4000

barrels of gunpowder were stored in the magazine outside

Corunna, and on the 13th this huge mass of explosives was

blown up.

A pause of three days occurred after Moore's footsore

soldiers limped into Corunna. The British transports had

not made their appearance, and had to be summoned from

Vigo. Soult's troops were almost as much exhausted as the

British, and it was not until the 14th that there were any

signs of the French onfall. Moore filled up the interval with

some grim preparations for embarkation. More than 4000

barrels of gunpowder were stored in the magazine outside

Corunna, and on the 13th this huge mass of explosives was

blown up.

Jumbo Map of Battle of Corunna (very slow: 300K)

The earth shook under the blast of the explosion, a wave of sound rolled with the majesty of thunder up the trembling hills and far over the quivering sea. The waves ran back from the beach. Into the blue sky shot a gigantic column of smoke, a black and mighty pillar that seemed to run beyond human vision into the azure depths. Then this aerial column wavered and broke; and back to earth rushed a tempest of stones and fragments of iron and wood, killing many persons.

Next all the foundered cavalry and artillery horses were shot. No less than 290 horses of the German Legion alone were in this way destroyed; and of' the horses of the 15th Hussars, 400 strong when they entered Spain, only fifteen were left. Betwixt a cavalryman and his horse the tie becomes very close, and the German dragoons and the English hussars expressed their feelings about the slaughter of their horses in characteristic fashion -- the hussars by loud and energetic swearing, the German dragoons by not a little sentimental weeping.

On the 14th the transports reached the bay, and Moore at once embarked his baggage, his sick, and his artillery. On the 16th, as the French still seemed reluctant to attack, Moore determined to ship his whole force. At noon he mounted his horse and rode off to visit his outposts, having given orders that the embarkation was to begin at four. At this moment the French columns were seen moving on the slopes of the hills looking down on Corunna. They were about to attack. As Moore gazed steadfastly at the huge columns coming into sight, his face lit up. The tragedy of the retreat was not to close without the stern rapture of battle and of victory.

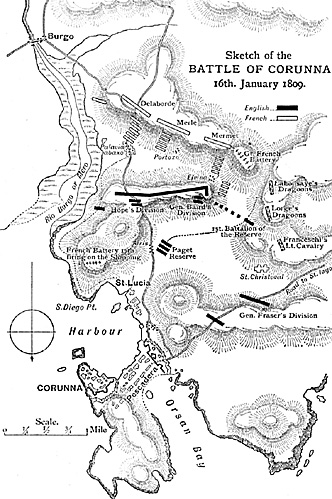

Soult had 20,000 troops and a strong artillery; Moore had only 14,500 men, with nine light piecessix-pounders. The French occupied a range of steep and rocky hills stretching in a curve from the Mero to the St. Jago road. This range constitutes the true nee of Corunna, but Moore had not troops enough to hold it. He fell back upon a lower and shorter range of hills nearer the town. The two ranges are not strictly parallel; they resemble, indeed, the two sides of a triangle, with the river Mero as a base.

The inner side of the triangle, held by the British, does not actually meet the range on which the French stood. A valley running clear down to Corunna broke the British line near the vertex of the triangle. Beyond the valley rises an isolated hill, a prolongation of the hilly ridge held by the British. Immediately opposite the gap in the British front the hill held by the French rises to a rocky crest, and to the summit of this Soult had dragged eleven heavy guns.

With these he could scourge the valley, rake the whole of the British line, which approached the obliquely, and could sweep the shoulder of the position, only 1200 yards distant, which looked over the the valley.

This rocky crest with its heavy battery, held by Mermet's division, formed Soult's left; his centre was occupied by Merle's, his right by Delaborde's.

On British side, Hope's division formed the left and centre; Baird's division, holding the hill under the stroke of Soult's great battery, constituted Moore's right. The isolated hill beyond the valley was held by the 28th and 91st, while a thin chain of rifle pickets stretched across the little valley betwixt the hill and Baird. Betwixt Soult's great battery and Baird's hill was the village of Elvina, held as an outpost by the pickets of the 50th.

The British line, looked at from Soult's position, was pierced by what seemed a fatal gap -- the valley betwixt Baird and the isolated hill held by the two regiments named. Soult attacked simultaneously along the whole British front, but the strength of his onfall was really flung on Baird. The great battery on the rocky crest we have described scourged Baird's hill with a tempest of shot. Then a heavy column of infantry came at the double down the slope of the French position, its officers, with brandished swords, leading, the men sending up a tumult of shouts, "Tuez! Tuez!" (Kill! kill!).

The British pickets were thrust in an instant out of Elvina. The French column, as it came on, broke into two. One column attacked the English hill boldly in front, the second brushed aside the rifle pickets which formed a screen across the valley, and tried to turn the shoulder of the hill, so as to take Baird's position in reverse.

The apparent gap in the English line, however, was in reality a death-trap for the French. The column that broke into it found itself scourged with a deadly musketry fire on both flanks. From the isolated hill, the 28th and 91st, reinforced by Paget's division, poured incessant volleys; from the 42nd on Baird's hill, drawn up at right angles to the British front, a fire as close and deadly rolled. The attack on the front of the hill was fiercely repelled; the column trying to force its way through the gap seemed to shrivel under the dreadful fire that smote it on either flank.

Charles Napier, afterwards the conqueror of

Scinde, was in command of the 50th on the front of Baird's

hill. He has left a description of the fight, which, for

mingled humour and fire, and as a picture of the tumult and

distraction of a great battle, can hardly be excelled in

English literature. Charles Napier has made history; but

this description shows that he could also have written it as

brilliantly as his brother, the historian of the Peninsular

War. Napier gives us a sort of verbal photograph of

Moore's bearing at this stage of the fight. He says:

Charles Napier, afterwards the conqueror of

Scinde, was in command of the 50th on the front of Baird's

hill. He has left a description of the fight, which, for

mingled humour and fire, and as a picture of the tumult and

distraction of a great battle, can hardly be excelled in

English literature. Charles Napier has made history; but

this description shows that he could also have written it as

brilliantly as his brother, the historian of the Peninsular

War. Napier gives us a sort of verbal photograph of

Moore's bearing at this stage of the fight. He says:

"I stood in front of my left wing on a knoll from whence the greatest part of the field could be seen, and my pickets were fifty yards below, disputing the ground with the French skirmishers, but a heavy French column, which had descended the mountain at a run, was coming on behind with great rapidity, and shouting, 'En avant, tue, tue! en avant, tue!' their cannon at the same time, plunging from above, ploughed the ground and tore our ranks. Suddenly I heard the gallop of horses, and turning, saw Moore. He came at speed, and pulled up so sharp and close, he seemed to have alighted from the air, man and horse looking at the approaching foe with an intentness that seemed to concentrate all feeling in their eyes. The sudden stop of the animal -- a creamcoloured one with black tail and mane-had cast the latter streaming forwards, its ears were pushed like horns, while its eyes flashed fire, and it out snorted loudly with expanded nostrils. My first thought was, 'It will be away like the wind;' but then I looked at the rider, and the horse was forgotten! Thrown on its haunches, the animal came sliding and dashing the dirt up with its forefeet, thus bending the General forward almost to its neck; but his head was thrown back, and his look more keenly piercing than I ever before saw it. He glanced to the right and left, and then fixed his eyes intently on the enemy's advancing column, at the same time grasping the reins with both his hands, and pressing the horse firmly with his knees; his body thus seemed to deal with the animal, while his mind was intent on the enemy, and his aspect was one of searching intenseness beyond the power of words to describe. For a while he looked, and then galloped to the left without uttering a word."

As a companion picture to Moore, Napier describes the general in command of his own division -- Lord William Bentinck -- ambling up on a quiet mule through the heavy fire and chatting with Napier, mule and general seeming equally indifferent to the flying bullets and the falling men. Bentinck, adds Napier, began discoursing on things in general "with more than his usual good-humour and placidity."

"I remember saying to myself," writes Napier, "this chap takes it coolly, or the devil's in it!"

When Bentinck and his mule ambled off, Napier, whose temper was of the fieriest, took the 50th forward, drove the French out of Elvina, fought his way up to the base of the crag from which Soult's great battery was thundering, and with some thirty privates attempted to storm it. Bentinck, however, had ordered back the main body of the regiment, Napier's little group was destroyed, and he himself taken prisoner by the French.

Meanwhile Hope had roughly flung back the columns attacking the British left and centre; the columns which had assailed Baird's hill were recoiling in confusion, and Moore saw that the moment had come for a counter- stroke. He was bringing up Paget's division to storm the great battery, and so thrust back Soult's left and tumble his line in ruins into the Mero.

But at that moment Moore himself was struck down. A cannon-shot smote him on the left shoulder, carrying away part of the collar-bone and leaving the arm hanging by the flesh. Moore was hurled from his horse by the stroke, but his eager spirit was fixed on the conflict raging in front of him, where the Black Watch was at that moment driving back the French column. The stricken general raised himself up on his right elbow, not a line in his face altering, and eagerly watched the struggle. Some soldiers of the 42nd ran up to carry Moore to the rear.

Hardinge, his aide-de-camp, proceeded to unbuckle his sword., but that seemed to touch the dying man's honour. " I had rather it should go out of the field with me," he said. Hardinge, noting Moore's absorption in the battle and indifference to his own wound, expressed a hope that he would recover. Moore turned his head round for a moment, looked composedly at the dreadful wound, and said, "No, Hardinge; I feel that to be impossible."

As the soldiers carried him off the field he repeatedly made them halt and turn, that he might watch the fight. A much-attached servant met the little group and broke into tears. "My friend," said Moore to him with a smile, "this is nothing!"

The scene in the room where Moore died was almost as pathetic as that in the cockpit of the Victory when Nelson met his fate. The dying soldier said to Colonel Anderson, "You know, Anderson, I have always wished to die this way."

"I hope," he said again and again, "That the people of England will be satisfied; I hope my country will do me justice." Then he would ask, "Are the French beaten?" Moore's thoughts turned presently to the youthful soldier who had commanded the reserve, and had shown a resolution, a coolness, and a mastery over his soldiers which no veteran could have surpassed. "Is Paget in the room?" he asked. He was told "No."

" Remember me to him," he whispered; then with emphasis, "Remember me to him. He is a fine fellow!"

Only once his voice broke when giving a last message for his mother. "I feel myself so strong," he said again, "I fear I shall be long dying."

But he was not. Death came with merciful swiftness. As night fell, while the thunder of the battle grew ever fainter in the distance, Moore's gallant spirit passed away.

Moore's death arrested and made imperfect the victory the British had won. Baird, his second in command, had been severely wounded, and Hope assumed direction of affairs. If the British reserves had been thrown frankly into the fight, it can hardly be doubted that Soult would have been-not merely defeated, but destroyed. But Hope held that enough had been done for glory. He forbore to press the retiring, French columns, marched his own regiments under cover of night to the shore, and embarked them swiftly and without confusion, Hill's brigade holding Corunna to cover the embarkation.

When morning came Soult discovered that the British army had vanished, and he advanced slowly over the scene of the battle of the previous day., Some of the French guns opened fire on the transports, but a British seventy-four thundered angrily back in reply, the fire ceased, and, with bellying sails, the transports drew off from the coast of Spain, with the wreck of Moore's gallant but ill-fated force.

Baird had been wounded by a grape-shot which struck him high on his left arm and shattered the bone. He walked with unchanged brow into Corunna, and, when the surgeons decided that the arm must be removed out of the socket, he sat, leaning his right arm on a table, without a sigh or groan while, with the rough surgery of the period, that dreadful operation was performed! It must be admitted that the standard of hardihood in the soldiers of that age was high.

The story of Moore's burial has been made immortal in Wolfe's noble lines, but severe historical accuracy is not usually characteristic of poetry. It is not true that "no useless coffin enclosed his breast," He was not buried "darkly, at dead of night."

A. grave was dug for the dead soldier on the ramparts by some men of the 9th Regiment; his body was wrapped in a military cloak and blanket, and laid in a rough coffin, and at eight o'clock in the morning, just as the transports were drawing off the shore, Moore was buried. Still his lonely tomb stands on the ramparts of Corunna. Southward are the wild and lofty hills across which, with so much suffering, he had brought his army. Nearer is the low range where he turned at bay and overthrew his pursuers. Above his grave stands a monument, reared by the hands of Frenchmen, bearing the brief and soldierly inscription, "John Moore, leader of the English armies, slain in battle, 1809."

Moore, some one has said, is known only because "a poet of a single song sang him an immortal dirge;" but this is an absurd estimate. If Wolfe had never written his famous lines, Moore, by force of character and the scale of his achievements, would have lived long in English memory. He had, perhaps, every quality of a great soldier save one. He lacked hopefulness. His courage was, it is true, serenely heroic. In personal character he had a touch of Tennyson's Sir Galahad. He was noble-minded, with a haughty scorn of falsehood and of meanness, and a devotion to duty which knew neither limit nor flaw. He had a curious faculty for touching the better nature of those about him. No man could be base or selfish while under his influence. His standard in soldiership was singularly high, and his mastery of the science of war has not often been surpassed in British military records.

But he was over-anxious. He lacked the iron steadfastness which is unmoved by the shock of disaster. His very sense of responsibility sometimes shadowed his clear intellect. He seemed to fail in the sense of perspective; -smaller difficulties that were near, that is, sometimes hid from him great advantages which were distant. Yet amongst the gallant soldiers who have fought and died for the honour of England, there is no loftier and more lovable figure than that of Sir John Moore.

Chapter IX: The Walcheran Expedition (Scheldt to Antwerp)

Back to War in the Peninsula Table of Contents

Back to ME-Books Napoleonic Bookshelf List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com