Wellesley would have moved direct on Lisbon, but in

the evening news came that General Anstruther, with his

brigade, and a fleet of storeships, had anchored off

Peniche. To cover their landing, Wellesley moved towards

the coast, and took up a position at Vimiero. Junot, on his

part, gathering up all his available strength, marched at

speed from Lisbon, drew under his standards the divisions

of Loison and Laborde, and on the 19th reached Torres

Vedras, nine miles distant from Vimiero, where Wellesley stood.

Wellesley would have moved direct on Lisbon, but in

the evening news came that General Anstruther, with his

brigade, and a fleet of storeships, had anchored off

Peniche. To cover their landing, Wellesley moved towards

the coast, and took up a position at Vimiero. Junot, on his

part, gathering up all his available strength, marched at

speed from Lisbon, drew under his standards the divisions

of Loison and Laborde, and on the 19th reached Torres

Vedras, nine miles distant from Vimiero, where Wellesley stood.

The French general was so strong in cavalry that he was able to draw his horsemen like a screen across his front, and conceal his own strength and movements from Wellesley's keen eye.

On the 20th, however, the British general had formed his plans. He would push betwixt Junot and the sea-coast, and cut him off from Lisbon. But at this moment Sir Harry Burrard, commander No. 2, arrived off the coast, and Wellesley had to suspend his movements and take his superior officer's instructions.

Burrard was a gallant soldier but a poor general. He was old, his imagination was frozen, the situation was strange, the responsibility great, and he told Wellesley bluntly he would not stir till Moore arrived with reinforcements. Wellesley urged that Junot, if not attacked, would certainly attack, and would thus be able to choose the time and place of battle which best suited himself. But nothing moved Burrard, and Wellesley returned to his camp in disgust.

Junot on the March

Junot, however, settled the question of strategy. He had to choose betwixt victory over the British or revolt at Lisbon, and the time for choice was of the briefest.

At the very moment Burrard arrested Wellesley's movement, Junot was marching to attack the English. All night he pushed through the long defile that led to Vimiero; at seven o'clock- on the morning of the 21st he was within four miles of the British position; at ten o'clock the fight of Vimiero was raging.

The news that Junot was moving was brought about midnight to Wellesley, who -- it is an amusing detail to learn -- was found, with his entire staff, sitting back to back on a long table in the rough quarters he occupied, "swinging their legs."

Wellesley took the news coolly, and refused to disturb his troops. The French, he guessed, after a long night march, would not attack at once, but would wait till morning.

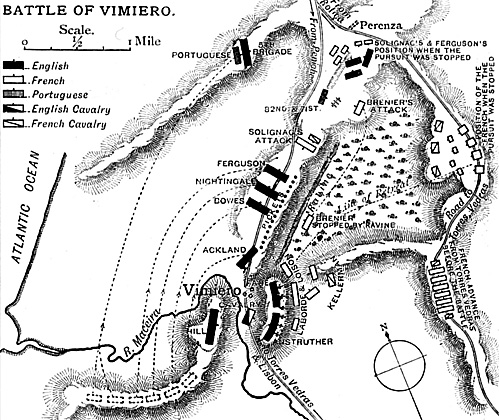

At Vimiero a range of hills from the north, hitherto

running parallel to the coast, curves round at a sharp angle,

and runs almost due west to the sea-board.

At Vimiero a range of hills from the north, hitherto

running parallel to the coast, curves round at a sharp angle,

and runs almost due west to the sea-board.

Jumbo Map of Battle of Vimiero (very slow: 253K)

The river Maceira breaks through the range at the very angle of the curving hills. Vimiero stands in front of the gap in the hills made by the river; in front of Vimiero, again, is a lower and isolated hill. This hill formed Wellesley's centre, and was held by Fane's and Anstruther's brigades.

On the heights in their rear was the reserve under Hill. The ridge swinging sharply round to the west formed the British right, and was hold by the brigades under Craufurd, Ferguson, Bowes, Nightingale, and Acland; the left, which consisted of a line of steep hills, with a sudden valley like a trench running at their base, was lightly held by the 40th regiment and some pickets.

Junot, a fine though impulsive soldier, saw Wellesley's battle-line before him: it formed the two sides of an obtuse triangle, with the hill on which stood the brigades of Fane and Anstruther at the vertex. Wellesley's right was strongly held, his left seemed almost naked of troops, and the deep ravine which made it unassailable by direct attack could not be detected from the point where Junot sat on his horse studying the English position.

With swift decision Junot launched Laborde against Wellesley's centre. Brennier led the main attack against the left, with Loison in support; while Kellerman, with a strong body of grenadiers and 1300 cavalry, formed the reserve. Wellesley read Junot's plan, and promptly marched the three brigades of Ferguson, Nightingale, and Bowes across the angle of his battle-line from the right wing to the left.

Laborde came on boldly, a mass of 6000 men, with a fringe of artillery fire -- an edge of white smoke and darting flame -- running before his columns. On the crest of the hill stood the 50th in line, with some Rifles. The 86th, the leading French regiment, plunged into the fight with fine courage, and the Rifles, who were thrown out as skirmishers, fell back before them.

The 50th, standing grimly in line, grew impatient at seeing the Rifles fall back. The steady line began to vibrate with passion, an angry shout went up: " Damn them! Charge, charge!"

Fane rode to and fro before his men to steady them. "Don't be too eager, men," he said coolly. But when the solid mass of the French column was visible over the crest, he gave the word to charge, and the 50th went forward with great vehemence. The French, a veteran regiment, for a moment stood firm, and the bayonets clashed together with a farheard ring. But the 50th were not to be denied, and after a moment's fierce wrestle, the French were driven in wild confusion and with much slaughter down the slope.

Center Attack

A still more vehement attack on the centre was made by Kellerman's grenadiers. They were choice soldiers, splendidly led, and they mounted the hill at the quick-step with loud cries, and actually pushed back the 43rd, which stood in their path. Rallying, however, the 43rd ran in again upon the French, slew 120 grenadiers with the bayonet, and sent the whole mass whirling in dust and confusion to the bottom of the hill.

A single company of the 20th dragoons constituted Wellesley's cavalry, and these were now sent at the broken French. As they rode at the gallop past Wellesley, his staff involuntarily clapped their hands in admiration. It was a handful of horsemen charging an army! Taylor led the charge, and, pushing too fiercely into the broken infantry, was slain. The handful of English horsemen, riding eagerly in pursuit, were in turn charged by an overwhelming force of French cavalry, and almost destroyed.

The French attack on the British left fared even worse than that on the centre. The first column, under Brennier, found itself barred by the deep ravine which formed a: natural ditch in front of the British position; the second column, under Solignac, marched in a wide curve round the head of the ravine, and climbed the hill with speed, expecting to take the British in reverse. But the French general had under-estimated Wellesley's tactics. Three British brigades, under Ferguson, Nightingale, and Bowes, stood drawn in steady lines across his path; a fourth, under Craufurd, was within striking distance of his flank.

Ferguson, a fiery Scotch soldier, attacked instantly and with resolution. The 36th, 40th, and 71st formed his line, and with one long level line of shining bayonets they closed on the enemy. Here again the French for a moment stood firm; and in a bayonet charge pushed home, where soldier closes on soldier along a wide front, the slaughter is quick and deadly.

The foremost rank of the Frenchmen fell, to quote the words of an actor in the fight, "like grass before the mower;" 300 French grenadiers slain by the bayonet were counted afterwards lying along the slope where the lines met. Solignac himself fell wounded, his colunin was broken into fragments, six of his guns were captured, and Ferguson, leaving the 82nd and 71st to guard the captured guns, pressed eagerly on in pursuit.

Suddenly on his flank out of the smoke-filled ravine emerged a solid French column, coming on at the quick- step, with drums beating, and officers, sword in hand, urging their men forward with fiery gestures. It was Brennier's brigade, that had at last found its way across the ravine. The 82nd and 71st, taken by surprise, for a moment were flung back and the guns recaptured. But rallying, the British charged afresh, drove back the French, re-took the guns, Brennier himself being made a prisoner.

The French were now defeated at every point. Ferguson's lines were closing round Solignac. Wellesley knew that Junot's last reserves bad been flung into the fight, while one-half the British army had not been engaged. The road to Torres Vedras was left open by the retreat of the French, and they could be cut off from Lisbon. But at this juncture Sir Harry Burrard, who had come on the scene of the battle some time before, but who had not interfered with Wellesley's movements, chose to assume command, and ordered all pursuit of the enemy to cease.

Ferguson, with Solignac's broken regiments under his very hand, was called back; the movement along the Torres Vedras road was arrested.

In vain Wellesley urged pursuit. "Sir Harry," he said, "now is your time to advance. The enemy are completely beaten. We shall be in Lisbon in three days."

But Burrard held that enough had been done. A French army had been overthrown, with the loss of thirteen guns, several hundred prisoners, and nearly 3000 killed and wounded. Wellesley, indeed, saw that Junot might be not merely defeated, but destroyed; but he failed to move Burrard's colder and more timid nature, and he turned away, saying to his aide-de-camp, "Well, then, there is nothing for us soldiers to do here except to go and shoot red-legged partridges!"

Burrard's contribution to the battle was that single unhappy order which arrested the British pursuit and left the victory incomplete, The next morning Sir Hew Dalrymple appeared on the scene, and Burrard's brief and ignoble command ended. The astonished British army had thus undergone three changes of commander within twenty-four hours!

Vimiero is memorable, not merely as being the first battle in the Peninsular War, but as the first in which the characteristic tactics of the French and the English were tried, and on an adequate scale, against each other.. Croker, in his "Journal," tells how Wellesley spent the last night before embarking for the Peninsula with him. Wellesley fell into a deep reverie, and was rallied on his silence.

"Why, to tell the truth," he said, "I was thinking of the French that I am going to fight. I have not seen them since the campaign in Flanders, when they were capital soldiers, and a dozen years of successes must have made them better still. They have beaten all the world, and are supposed to be invincible. They have, besides, it seems, a new system, which has outmaneuvered and overwhelmed all the armies of Europe. But no matter. My die is cast; they may overwhelm me, but I don't think they will outmaneuvere me -- in the first. place, because I am not afraid of them, as everybody else appears to be; and secondly, because if what I hear of their system of maneuveres be true, I think it a false one against troops steady enough, as I hope mine will be, to receive them with the bayonet. I suspect that all the Continental armies were more than half-beaten before the battle was begun. I, at least, will not be frightened beforehand."

Wellesley had guessed the flaw in French tactics. They uniformly attacked in column, and such an attack, if pushed resolutely home, is, except against troops of the highest quality, overwhelming. The narrow front of the column gives it the rending power of a wedge; its weight and mass supply almost irresistible momentum. The column, too, with the menace of its charge and its massive depth of files, impresses the imagination of the body against which it is launched, and overthrows it more by moral than even physical pressure. But Wellesley knew the British soldier. Whether from mere defect of imagination, or from native and rough-fibred valour, British soldiers would meet coolly, in slender extended line, the onfall of, the most massive column. And if in such a conflict the line stands firm, it has a fatal advantage over the column. Its far-stretching front of fire crushes the head, and galls the flanks of the attacking body. One musket, in a word, is answered and overborne by the fire of ten; and under such conditions the column almost inevitably goes to pieces.

Napier, a soldier familiar with battle, paints in vivid

colours the experiences of a column met by steady troops in line.

Napier, a soldier familiar with battle, paints in vivid

colours the experiences of a column met by steady troops in line.

"The repugnance of men to trample on their own dead and wounded, the cries and groans of the latter, and the whistling of cannonshots as they tear open the ranks, produce disorder, especially in the centre of attacking columns, which, blinded by smoke, unsteadfast of footing, bewildered by words of command coming from a multitude of officers crowded together, can neither see what is taking place, nor advance, nor retreat, without increasing the confusion. No example of courage can be useful, no moral effect produced by the spirit of individuals, except upon the head, which is often firm, and even victorious, when the rear is flying in terror."

Marshal Bugeaud has described, from. the French standpoint, the same scene: "About 1000 yards from the English line," he says, "the men become excited, speak to one another, and hurry their march; the column begins to be a little confused. The English remain quite silent, with ordered arms, and from their steadiness appear to be a long red wall. This steadiness invariably produces an effect on the young soldier. Very soon we get nearer, shouting 'Vive l'Empereur! On avant! A la bayonette!' Shakos are raised on the muzzles of the muskets, the column begins to double. The agitation produces a tumult; shots are fired as we advance. The English line remains still, silent and immovable, with ordered arms, even when we are only 300 paces distant, and it appears to ignore the storm about to break.

"The contrast is striking; in our inmost thoughts each feels that the enemy is a long time in firing, and that this fire, reserved for so long, will be very unpleasant when it does come. Our ardour cools. The moral power of steadiness which nothing shakes (even if it be only in appearance) over disorder which stupefies itself with noise, overcomes our minds. At this moment of intense excitement the English wall shoulders arms, an indescribable feeling roots many of our men to the ground; they begin to fire. The enemy's steady concentrated volleys sweep our ranks; decimated, we turn round, seeking to recover our equilibrium; then three deafening cheers break the silence of our opponents; at the third they are on us and pushing our disorganised flight. But, to our great surprise, they do not push their advantage beyond a hundred yards, retiring calmly to their lines to await a second attack."

Another gallant soldier of the Peninsula, Leith Ray, describes not so much the defect in the method of French attack as the limit in the fighting quality of French troops.

"In mounting steeps defended by troops," he says, "in making attacks in large bodies where a great crisis is at issue, in forcing on under fire until all difficulties but the personal, th e close conflict with his opponent, has been overcome, the French soldier appears to be unequalled. But when perseverance has placed him on equal ground, when he apparently has obtained a chance of successfully terminating his attack, he becomes no longer formidable, and appears paralysed by the immediate presence of his opponents -- a strange and inexplicable result of so much gallantry, such gaiety, so much recklessness of danger. It is only to be accounted for by the supposition that the physical composition of the Frenchman does not permit the effervescence to subsist beyond a certain exertion, that, if unchecked, might have continued buoyant, but, being resolutely met, becomes depressed and vanquished."

Wellesley had certainly shown in these first contests with the French that he was not " frightened beforehand; " and thrice in the contest, of Vimiero his soldiers had met in line and crushed the attack of the French in column. British methods thus had been fairly tried against French methods, and the result was written in blood-red characters on the field at Vimiero.

Dalrymple hesitated betwixt Burrard's policy and Wellesley's for a whole day, but decided to advance on the 23rd. At midday on the 23rd, however, when the British were about to inove, a cluster of French horsemen, escorting a flag of truce, rode into the lines. It was Kellerman with a proposal for an armistice until a convention should be drawn up for the evacuation of Portugal. Dalrymple welcomed the proposal. It seemed to promise the fruits of victory without the perils of another battle. Wellesley, with more soldierly instinct, wished to press on without pause. Junot, he believed, would not have proposed a convention if he had any hope of holding Portugal.

Dalrymple, however, had much more of the caution of age than of the, energy of youth. He accepted the French proposals, and what is known as the Convention of Cintra followed. The French were to evacuate Portugal, and, with all their artillery, arms, and baggage, were to be transported in British ships to France. One article of the Convention stipulated that plunder was not to be carried off by the French; but to persuade a French army to surrender its booty was a feat beyond the ingenuity of British diplomacy.

The French had stripped churches, art galleries, palaces, and warehouses of everything portable, and were loaded With booty. The troops who had limped naked into Lisbon proposed to sail from it with baggage enough to load a fleet of transports. Junot himself demanded five transports for his own "private property." With much distracted shrieking, and some actual scuffling, the French were compelled to disgorge much of their plunder, but they yet contrived to carry off a vast amount of booty.

The Convention of Cintra gave Portugal, with its capital and all its strong places, into the hands of the British, and Junot's troops, that bad entered Lisbon as conquerors, were conveyed ignobly in British transports back to France. But in Great Britain itself the news of the Convention was received with angry disgust. It called forth, indeed, a louder explosion of wrath than if the entire British army had been driven to re-embark, or had even been destroyed!

At Baylen, Spanish peasants had compelled a French marshal and his army to surrender as prisoners; at Cintra, British generals had allowed a beaten French army to march off with what seemed to be the honours. of war and the plunder of a country.

A court of inquiry, consisting of seven British generals, sat at Chelsea, and spent six weeks taking evidence on the subject. Wellesley, Burrard, and Dalrymple were practically put on their trial. Six generals approved and one disapproved of the armistice; four generals, approved of the Convention, three disapproved. The report of the court of inquiry dwells with wide-eyed astonishment on "the extraordinary circumstances under which two new commanding generals arrived from the ocean and joined the army, the one during, and the other immediately after, a battle, and these necessarily superseding each other, and both the original commander, within the space of twenty-four hours."

The world still shares that wonder of the six major- generals who formed the court of inquiry. The inquiry, however, made it clear that Wellesley had been fatally hampered by the elderly and leisurely generals put over him, and he emerged from the trial with reputation undamaged.

The Convention, with all its defects, was undoubtedly a blow to the French, a substantial advantage for the British. Napoleon summed up the situation in a sentence: "I was going," he says, "to send Junot before a council of war, when, fortunately, the English tried their generals, and saved me the pain of punishing an old friend."

Chapter VI: Moore and Napoleon

Back to War in the Peninsula Table of Contents

Back to ME-Books Napoleonic Bookshelf List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com