Naploeon has supplied the world with many

contradictory explanations of his fatal policy in Spain,

some of them addressed to his contemporaries, some of

them to posterity. Most of them, it may be added, are pure

inventions. For Napoleon lied as diligently to posterity as

he did to those immediately about him, whom it was his

interest for the moment to deceive.

Naploeon has supplied the world with many

contradictory explanations of his fatal policy in Spain,

some of them addressed to his contemporaries, some of

them to posterity. Most of them, it may be added, are pure

inventions. For Napoleon lied as diligently to posterity as

he did to those immediately about him, whom it was his

interest for the moment to deceive.

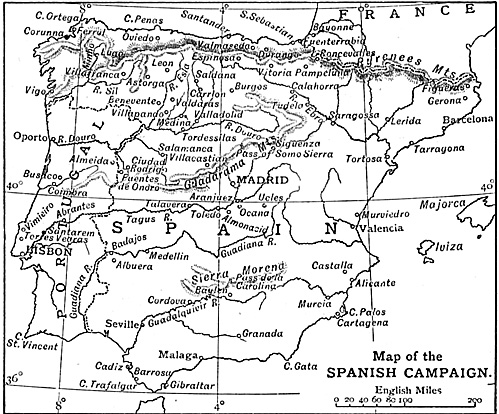

Jumbo Map of Spain (very slow: 286K)

Perhaps the nearest approach he ever made to frankness as to his Spanish policy is in the explanation he offered to Metternich on August 25, 1808. "I went to Spain," he said, "because that country, instead of putting its money into the navy which I required against England, spent it all in reinforcing its army, which could only be used against me. And then the throne was occupied by Bourbons. They are my personal enemies...They and I cannot occupy thrones at the same time in Europe."

Napoleon's motive was, in short, compounded of suspicion, hate, and unashamed selfishness. He hated the Bourbons and the English. He suspected, with the mistrust natural to the Corsican side of his nature, that even so servile an ally as Spain had hitherto been might some day turn against him. For Spain the single end of existence was to be Napoleon's tool. Had it treasures? Not to expend them on "the ships which I required," says Napoleon, was an inexpiable offence! Then he wanted a new crown for the head of a Bonaparte. Above all, Spain must become French to complete the zone of the Continental system.

As a mere study in colossal and artistic duplicity, no chapter of Napoleon's career, perhaps, quite compares with his Spanish diplomacy in 1808. During those fateful nineteen days at Tilsit, when the two Emperors arranged a new Europe, partitioning kingdoms and shifting nations and governments like pawns on a chessboard, there can be no doubt that Spain was surrendered to Napoleon exactly as Finland was to Alexander. But Napoleon arranged the Spanish comedy with the skill of a great artist. Spain was to begin by being his accomplice it was to end by becoming his victim.

He gave Portugal the choice of declaring war against England or of being attacked by France. Before an answer to his ultimatum was received, he had agreed with Spain for the partition of Portugal. One-third was to be given as a principality to Godoy; another third was to form a principality for a cadet of the Spanish House; the remaining third was to be kept in hand as a counter in the diplomatic game, when next a peace had to be negotiated. Portugal was thus to be as remorselessly partitioned as Poland had been.

To carry out this ingenious bit of vivisection, 30,000 men under Junot were to march across Spain and seize Lisbon. Junot, however, received instructions from Napoleon to make a military survey of Spain as he crossed it, and to put French garrisons into every place in Portugal he occupied. Napoleon, in a word, was not merely about to cheat his accomplice of its share of the spoil; he was already arranging to plunder it of its own possessions.

On October 28, 1807, Napoleon writes to his Minister of War: " I desire my troops shall arrive at Lisbon as soon as possible, to seize all English merchandise. I desire they shall, if possible, go there as friends, in order to take possession of the Portuguese fleet."

Junot was instructed by Napoleon himself to issue a proclamation declaring that "the shedding of blood is repugnant to the noble heart of the Emperor Napoleon, and if you will receive us as auxiliaries, all will be well."

By these means, Napoleon explains cynically, "Junot may contrive to get to Lisbon as an auxiliary. The date of his arrival will be calculated here to a couple of days, and twenty-four hours later a courier will be sent to inform him that the Portuguese proposals have not been accepted, and he is to treat the country as that of an enemy."

"Eight or ten ships of war and all those dockyards," Napoleon coolly adds, "would be an immense advantage to us."

Napoleon understood how much depended on the speed of Junot's march. If Lisbon could be reached in time, not only would the city become a prey, but the Portuguese fleet would be seized; and, added to a Russian squadron of twelve sail of the line on its way to that port, would become, with the Spanish fleet, the left wing of that stupendous, if somewhat visionary, fleet of not less than 180 ships of the line, which, in the chambers of Napoleon's plotting brain, was already taking form.

So Junot was charged to press on without regard to the suffering or the lives of his troops; and, as the French general saw glittering before him the air-drawn likeness of a kingly crown, he obeyed these instructions literally.

Over 200 miles of mountain passes, through hunger and tempest, lie hurried his troops, until of a column which at Alcantara had numbered 25,000 men, only 2000 were left to limp into Lisbon, footsore, ragged, sickly, more like a procession of incurables from some great hospital than a march of soldiers. Some dropped in the streets, says Southey, others lay down in the porches till the passers-by gave them food.

Lisbon was a city of 300,000 inhabitants, with a garrison of 14,000 troops; a powerful British squadron under Sir Sidney Smith lay at the entrance of the Tagus ready to help. But the mere imagination of Napoleon's power, like some mighty and threatening phantom, seemed to enter Lisbon with Junot's footsore and ragged grenadiers, and the city fell without a stroke.

Meanwhile the King of Spain, by a solemn treaty, was assured of a share not only of Portugal, but of all her colonies. With a touch of sardonic humour Napoleon even invented a now title for the monarch whom he proposed to discrown. The King of Spain was to have the title of "the Emperor of the two Americas!" It was easy to be generous of glittering syllables to the dupe whom it was intended to plunder of a kingdom.

The domestic troubles and scandals of the Spanish court gave Napoleon his opportunity. Charles IV. was a senile cripple. The Queen was a false and shameless wife. Her lover, Godoy, practically ruled Spain. The heir- apparent, Ferdinand, was a son without affection and without character. The Spanish court was a witches' dance of intrigues and hatreds -- Ferdinand plotting against his father; the shameless Queen, with her lover and the dishonoured King, plotting against Ferdinand. There is no space to tell here how Napoleon played with these vile figures as his tools, and meanwhile silently pushed his troops into Spain, seizing one stronghold after another. The King accused his son to Napoleon; Ferdinand appealed to Napoleon for protection from his father. Napoleon listened to each, fanned their passions to a fiercer heat, and still pushed new troops through the Pyrenees.

Portuguese Exile

Junot by this time had reached Lisbon, and the royal family of Portugal had taken shipping for Brazil under the protection of a British squadron. Junot published a decree, drawn up by Napoleon himself, which began with the sonorous announcement, "The House of Braganza has ceased to reign," and ended by directing a bottle of wine to be given to each French soldier in Portugal every day at the Portuguese cost.

"To abolish an ancient royalty in a single sentence was picturesque; the bottle of wine," says Lanfrey, " is less epic, but it brings the real truth before us." There was always a basis of plunder to Napoleon's conquests, and for Napoleon's appetite nothing was too little and nothing too big. The French soldier was to have a daily bottle of wine at Portuguese expense; Napoleon himself imposed a tribute of 200 million francs on the Portuguese treasury.

Murat was now sent to Spain in command of the French forces there, with instructions to push on towards Madrid, get possession of as many strong places as possible, and announce that Napoleon himself was coming "to besiege Gibraltar." Murat, it may be added, was allowed to entertain the hope of himself grasping the Spanish crown.

The French hitherto, as it was believed they were supporting Ferdinand against the old king and the much- hated Godoy, had been received as friends; but Spanish jealousy was now taking fire. The old king, wearied of the struggle, abdicated in favour of his son, who assumed the title of Ferdinand VII., and the event was welcomed with universal delight.

But it by no means suited Napoleon's plans to have a young and popular king instead of one who was old and hated. Murat silently ignored Ferdinand VII. He persuaded Charles to withdraw his abdication and declare it had been extorted from him by force.

"You must act as if the old king were still reigning," Napoleon wrote to his general on March 27. On the same day he offered the Spanish throne to his brother Louis, then King of Holland.

Three days afterwards, Napoleon wrote again to Murat, "You must re-establish Charles IV at the Escurial, and declare that he governs in Spain;" but the unfortunate king was only to discharge the office of a royal warming-pan for a Bonaparte.

Long afterwards Napoleon invented a letter, dated March 29, in which he rebukes Murat for entering Madrid with such precipitation, and warns him that he may kindle a national uprising in Spain. This letter is a mere forgery. It was intended to deceive history, and save Napoleon's credit at the expense of Murat's. Napoleon, as a matter of fact, directed by the most explicit instructions every step Murat took.

Meanwhile the two mock kings of Spain were forced to carry their disputes in person to Napoleon at Bayonne. "If the abdication of Charles was purely voluntary," Napoleon wrote to Ferdinand, "I shall acknowledge your Royal Highness as King of Spain." Yet at that moment Napoleon's plan was complete for putting his own brother on the Spanish throne.

Ferdinand Out, Joseph In

On April 20 the unhappy Ferdinand crossed the tiny stream that separates Spain from France, and met Napoleon at Bayonne. He found himself a prisoner, and was bluntly told he must renounce the crown of Spain. He proved unexpectedly obstinate. The old king and his queen, with Godoy, were brought on the scene. They overwhelmed the unhappy prince with curses. His amazing mother, in her husband's presence, denied his legitimacy.

Napoleon gave him the choice of abandoning his birthright or of being tried as a rebel. In the end Ferdinand surrendered the crown to his father, who had already transferred it to Napoleon. By a second act of renunciation Ferdinand himself formally abdicated in favour of Napoleon, father and son receiving residences in France and annuities amounting to £ 500,000 a year.

Napoleon, for this modest price, bought Spain and all her colonies, but, with a touch of cynical humour, he made these pensions a charge on the Spanish revenues. The price for which Spain was sold must, in a word, be paid in Spanish coin and out of Spanish pockets! Both the old king and Ferdinand, it may be added -- not without a certain sense of satisfaction -- found much difficulty in extracting from Napoleon even the poor sum for which they had sold him a crown.

Ferdinand, later, found it difficult to forget that he was of the royal caste, and wrote to Napoleon as his "cousin."

"Try to make Monsieur de San Carlos understand," Napoleon wrote to Talleyrand, "that this is ridiculous, He must call me Sire!"

Napoleon believed the whole transaction was now a shining success. He foresaw no difficulties; he anticipated no war. His claim to the new throne was fortified by the double renunciation of father and son in his favour. He was, he persuaded himself, the heir of the Bourbons, not their supplanter. A strip of parchment, scribbled over with lies, constituted a valid title to a throne i A nation might be transferred, he believed, with a drop of ink, and of such curiously dirty ink!

On May 14 he wrote to Cambaceres: "Opinion in Spain is taking the direction I desire. Tranquillity is everywhere established."

That was a profound mistake. Napoleon omitted from his calculation human nature, especially Spanish human nature. He thought, when he had tricked a senile monarch into abdication and terrified his worthless heir-apparent into a surrender of his rights, all was ended.

He forgot that there remained the Spanish people, ignorant, superstitious, half-savage; but hot-blooded, proud, revengeful. A nation by temper unsuited, perhaps, to great and combined movements; but, alike by its virtues and vices, fitted beyond any other nation of Europe to maintain a guerilla warfare, cruel, bloody, revengeful, tireless; a conflagration that ran like flame in dry grass, and yet had the inextinguishable quality of the ancient Greek fire.

Back to War in the Peninsula Table of Contents

Back to ME-Books Napoleonic Bookshelf List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com