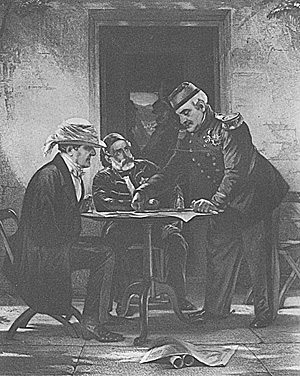

Left to right: Lord Raglan, Omar Pasha, and General Pelissier: at a council before the assault of the Mamelon.

Marshal Vaillant, comparing him with Canrobert, said, "Pelissier will lose 14,000 men for a great

result at once, while Canrobert would lose the same number

by driblets, without obtaining any advantage."

General Changarnier bore stronger testimony: "If there

was an insurrection, I should not hesitate to burn one of the

quarters of Paris. Pelissier would not shrink from burning the

whole." But it would do him great injustice to imagine that he

was merely a man of dogged resolution. He was not only a

soldier of great experience and distinction in Algerian

warfare, but took strong, clear views of strategical problems,

and expressed them in a correspondingly strong, clear style,

indicative of great sagacity. And

there lay before him, when he assumed the command, a

problem not easy to solve, yet demanding immediate

solution, and of vast importance. It was whether to put in

execution the project of the Emperor and Niel, or to devote

all his forces to pushing the siege.

Now there is no doubt that the design of defeating the

Russian field army, and severing the communication between

the interior of Russia and Sebastopol, would, if successful,

have speedily caused the surrender of the place. So far the

view was sound. But its two advocates erred in insisting on

treating it as if it were the only project which rendered

success possible, and in denying that the siege operations

contained any promise of victory. For there were several

circumstances which clearly pointed to the probability, nay

certainty, of the capture of the south side of Sebastopol on

the plan hitherto pursued. The enemy had never taken

from the Allies an inch of ground on which they had once

established themselves. If the Russians had not abandoned all

intention of attempting to raise the siege by an attack with

their field army, the Allies were confident of defeating any

such enterprise. There were signs that if the material of war in

Sebastopol showed no token of exhaustion, yet the trained

seamen who worked the guns were greatly reduced in

numbers. The besiegers' fire could always establish a

superiority, constantly increasing, over that of the place.

And, finally, the enemy's losses must, from the nature of

the case, continue to be immensely greater than those of the

Allies. In the preceding month the garrison of Sebastopol had lost more than 10,000 men, and there were good grounds for believing that the whole of the Russian Forces now in the Crimea scarcely numbered more than 100,000

men. It was certain, therefore, that should the Allies

persevere with the siege, the day, though not yet near, would

come when the enemy's fire would be overpowered, his works

stormed, and the south side rendered untenable.

Firm Grasp

Pelissier's mode of grasping this problem is first

shown in a letter which he wrote to Canrobert while that

general was still Commander-in- Chief He first expressed his

belief that the Allies, by pressing the attack on the works,

could certainly render themselves masters of Sebastopol;

"Difficult," he says, "but possible." Therefore he proposes,

before all things, to push the siege to extremity, without

regard to what was outside of it. Nevertheless, in case an

exterior operation should be 11 inexorably commanded by the

Emperor," he has his plan for that. But he presently shows that

this was merely a concession to the weakness of another, by

explaining that, before anything of that kind can take place, the

Russians must be shut up so completely in their works that no

sortie need be feared, and that the first operations must

therefore be the capture of the Mamelon and the White

Works at any price. "If there are to be operations in the

field, they must only take place after we have restricted the

Russians absolutely to their defences, and have thus achieved

security for our base of operations."

He meant by this to insist on the necessity of driving

the Russians from all those

works which, to the great annoyance and injury of the Allies,

they had pushed out beyond the general line of entrenchment.

He had given a practical illustration of this view, on the 1st

May, when he was still only the commander of the 1st Corps

in front of the town. Todleben had, on the 23d April, effected

some large lodgments of rifle-pits between the town ravine

and the next one on his right of it, and in the ensuing week,

employing a great number of labourers, and a strong force to

protect them, had formed these into an important work,

closed and partially armed, and so close to the French

trenches and so menacing to them, by stretching towards their

flanks, that it would have immediately become a most serious

addition to the difficulties of the siege. Pelissier so

strongly represented to Canrobert the necessity of driving the

Russians out of it at all hazards that he was allowed to have his

way. In two hand-to-hand encounters of considerable forces

on both sides, on the 1st and 2d May, the French were so

completely successful that they not only took the

counterguard, but converted it into part of their own siege

works, within 150 yards of the main line in front of it, with a

loss to them of 600, to the Russians of 900 men.

In a letter to Bosquet, written immediately after he

took command of the army, Pelissier discusses the

alternative plans. The difficulties offered by the ground which

the enemy's field army occupied, the want of information

respecting its strength and positions, the danger of operating

through long defiles with large forces,

the perils of a retreat in case of failure, these and other

reasons caused him to reject, or at least to postpone, the

Emperor's scheme "without regret," as he phrased it.

"I am very determined," said this clear-seeing man, "not to

fling myself into the unknown, to shun adventures, and to act

only on sound knowledge, with all the enlightenment needful

for the rational conduct of an army." He then announces his

intention of extending the part of the army not engaged in the

siege along the valley of the Tchernaya, so as to get air, water,

elbow-room, and consequently health, and from thence to

study the country for future operations, by reconnaissances,

and force the enemy to spread themselves.

"But," he adds, "all this is only the prelude to an operation

much more important and more decisive in my eyes, the

storming and occupation of the Mamelon and White Works. I

do not disguise from myself that the conquest of these counter-

approaches will cost us certain sacrifices; but whatever they

cost, I mean to have them."

Then, after detailing the features of his plan, he observes,

"All this may be thorny, but it is possible, and I have

irrevocably made up my mind to undertake it." Here, then, was

a general who had occupied the firm ground of knowing what

he meant to do, and setting about it with an unchangeable

purpose. But he did not keep his opinions for his generals

only. Niel noted the new commander's course with great

disquietude, and even felt justified, in the strength of being the

Emperor's emissary, to offer to his chief, in a note written in

reply to a request for his view of affairs, a strong remonstrance.

He said his views remained the same as always; that to

attack without first investing the place would lead to nothing

except after bloody struggles; that he could not understand

why the Emperor's plan was to be abandoned ; and that the

persistence of Pelissier in his projects would entail every kind

of disaster. Scarcely had Pelissier received this when he

telegraphed thus to the Minister of War, for the Emperor's

information:

"The project of marching two armies, from Aloushta on

Simpheropol, and from Baidar on Bakshisarai, is full of

difficulties and risk. Direct investment, by attacking the

Mackenzie heights, would cost as dear as the assault of the

place, and the result would be very uncertain. I have arranged

with Lord Raglan for the storming of the advanced works, the

occupation of the Tchernaya, and finally, for an operation on

Kertch. . . . All these movements are in train."

This he explained fully in a letter to Vaillant next day, and

asked for complete latitude of action. When we remember

that Louis Napoleon was an absolute sovereign, that he had

just raised Pelissier to the chief command, that he was the

fountain of honours and advancement, and that, if he had set

this self-willed general up with one hand, he could pull him

down with the other, it must be admitted that, in thus opposing

the cherished scheme of his master, P61issier showed

himself an uncommonly strong man.

To the Emperor and his Minister, absorbed in

contemplation of the excellences of their plan, and hoping to

hear that it was in process of accomplishment,

this uncivil treatment of it caused something like

consternation. The stout warrior at one end of the wire was

arousing great perturbation and resentment in the Imperial

theorist at the other.

At first some angry messages were flashed to the Crimea --

one from Vaillant to Niel, relating to the expedition to Kertch:

"This news to-day is a great trouble. What! generals and

admirals, not one of them thought it his duty to consult the

Government on an affair of this importance!"

Then the Emperor sent a rebuke to his unappreciative

subordinate: "I have confidence in you," he said, "and I don't

pretend to command the army from here," ("But you do!" was

probably Pelissier's comment); "however, I must tell you my

opinion, and you ought to pay regard to it. A great effort must

be made to beat the Russian army, in order to invest the place.

To gain space and grass is not sufficient just now." (this in

sarcastic reference to Missier's reasons for extending the army).

" If you scatter your forces, instead of concentrating them,

you will do nothing decisive, and will lose precious time. The

Allies have i8o,ooo men in the Crimea. Anything may be

attempted with such a force, but to maneuvre is the right

course, not to take the bull by the horns; and the way to

maneuvre is to threaten the weak sides of the enemy. The weak

side of the Russians seems to me to be their left wing. If you

send 14,000 men to Kertch, you weaken yourself uselessly ; it

is to avow that there is nothing serious to attempt, for one

does not willingly weaken one's self on the eve of battle.

Weigh all this carefully."

Resolute

But, whether weighed or not, these arguments had not the slightest

effect on the mind of this resolute, even refractory, man. It

might be all very well for an Emperor to amuse himself with

making plans ; it was for a general to conduct operations.

Seeing all this, and knowing how indispensable was Pelissier,

Vaillant took a very judicious course. He desired Niel to aim

at moderating P61issier's too strong style of expression The

General was to be made to understand that the most complete

confidence was reposed in him, and to be adjured to assume

that as a basis in everything he might write. Whether Niel

ever found an opportunity of discharging this mission seems

doubtful, for he is shortly afterwards found uttering a

lamentable wail, in a letter to the Minister. "At yesterday's

meeting," he says, "General Pelissier imposed silence on me

with indescribable harshness, because I spoke of the dangers

which characterise vigorous actions with large masses at great

distances apart. We were in presence of English officers; I

saw he was irritated, and I wished at any price to avoid a scene

which would have rendered my relations with him impossible."

No matter whose emissary he was, Niel must know his

place. There was no doing anything with so intractable a chief;

he had his own way, and the French Army had a commander.

Pelissier's two first steps towards the execution of

his projects, namely, an attack on an important outwork and

the expedition to Kertch, took place at the same date, the 22d

May, when he had been six days in command. The first of

these was caused by a new enterprise of the indomitable Todleben. Between the Central Bastion and the bastion near the Quarantine Bay the line of

defence was a loop-holed wall, strengthened behind with

earth, but much battered by the heavy fire directed on it.

Seeing its precarious state, Todleben resolved to cover it

with a salient earthwork on a ridge in front, where he had

already placed rows of rifle pits. Between these pits and the

French trenches was a cemetery, lying in a green hollow,

having in its midst a small church, surrounded by crosses and

headstones. Once peaceful as any country churchyard in

England, it had now for months been an arena of conflict,

where riflemen had crouched in the grass of the graves, or

lurked in the shadow of the tombstones. The French

trenches were already close to its southern wall, when

Todleben, on the night of the 21st, began his outwork with

characteristic vigour with 2400 workmen with spade and

pickaxe, while 6000 infantry, and many guns bearing on the

ground in front, guarded them. But the French also were

making a trench that night, therefore both parties had an

interest in keeping their batteries quiet. But morning showed

that while the French, with their working party of ordinary

strength, had made about 150 yards of trench, the Russians

had made more than 1000 yards, besides a supplementary

work close to the head of Quarantine Bay. And these works

were not to play a defensive part merely; when armed, they

would rake the French trenches, and form a new and serious

obstacle to the progress of the siege. Therefore Missier

ordered that the new works should be attacked that night; the enemy was

equally resolved to defend them; and it so happened that about

6000, men were devoted to the purpose on each side. All the

guns, Russian and French, that could aid the infantry were laid

on their objects, ready to open. At nine on the night of the 22d

the fight began, and continued without intermission till three

in the morning. There was a glimmering moon, and against a

low bank of clouds the flashes of the guns marked the hostile

lines; the rattle of small-arms resounded through the night,

and at times a cheer, rising out of the gloom, showed where a

charge had been led, or some advantage won. Many times had

each side gained a temporary success; but as the French could

not remain in the work by day, under the fire of the place, the

Russians still held it in the morning, though it had cost them

dear. They had lost 2650 men; the French, 1800.

It so happened that the neighbouring bay of Kamiesch

had presented, on this same 22d, an unusually busy scene, for

the troops destined for the expedition to Kertch were

embarking there. From the ships they heard the conflict

raging at no great distance. In the morning they sailed on their

enterprise. Unluckily for the Russians, one of their

posts, from a tower of observation, saw and signalled that

large forces were in movement from the harbour.

Gortschakoff imagined that they were about to be landed on

the coast for an attack on his forces in the field. He

concluded he could spare no troops for another fight in the

trenches from his army, which lay between Mackenzie's Farm and the

heights of the Belbek. Therefore, only two battalions were to

hold the new work. If the French should prove to have had

enough of fighting the night before, these would suffice to

protect the completion of the work; but if attacked by

superior numbers, they must withdraw. The French did

come on again that night in great force, drove out the guard,

and converted the line of trench into a parallel of their own.

This night the losses were about 400 on each side.

Kertch Expedition

The much-talked-of expedition to Kertch had a very

practical object. The eastern point of the lozenge which the

outline of the Crimea forms runs in a long, narrow isthmus

towards the Circassian coast of the Black Sea, from which it

is separated by the narrow straits of Kertch, and these give

access, from the waters of the Euxine, to those of the inland

Sea of Azoz. Into this sea the River Don empties itself,

and thus the resources of large districts on its banks, and of

Circassia, can be swept into the isthmus ; and the superiority

of this route, compared with that along the wretched roads of

Southern Russia, and through the barren country by Perekop

to Simpheropol, had made it the great line of supply to

Gortschakoff's army. The Sea of Azoz was thronged with

craft, occupied in transporting stores to great depots on the

shores of the isthmus. Taganrog, on the shore of the Sea of

Azoz, near the mouth of the Don, was a considerable town,

and in former days had even, from its pleasant situation, been

thought of for the capital of Russia. The whole region was at this time specially full of business and activity.

The ships reached the straits of Kertch on the early

morning of the 24th. They bore, in all, French, Turks, and

English, 15,000 infantry, and five field batteries. There were

about 9000 Russians in the isthmus, of which 3000 were

cavalry. There were batteries guarding the straits, armed with

sixty-two heavy guns, and some forty others, unmounted, of

large calibre. And there had been plenty of time to prepare for

an attack, since the fiasco of three weeks earlier had warned

the enemy. It might have been expected that, with such

means at his disposal, General Wrangel, who commanded in

the isthmus, would have made at least some show of

resistance. But seeing how exposed his forces were, in their

straitened position, to be cut off by a landing in their rear, he

made haste to withdraw them, at the same time destroying his

coast batteries, while, of fourteen war-vessels, ten were burnt

by their crews. The Allied Squadrons therefore passed

into the straits without molestation. The landing of the troops

was effected the same night, in a bay a few miles from the

town of Kertch, which they entered early next morning, while

a flotilla of vessels of light draught passed into the Sea of

Azoz. There they captured or destroyed all the great number

of vessels engaged in transporting supplies for Gortschakoff's

army, as well as vast quantities of corn, flour, and stores. At

one point they came on the wrecks of the remaining four

steamers of the Russian Naval Squadron, destroyed by

order of its commander. A complete clearance of everything

that could aid the Forces in the Crimea was made throughout

the shores of the Sea of Azoz. At Taganrog, the depot of

the immense supplies brought down the River Don, where

some semblance of opposition was made by the garrison, the

destruction of the stores on the beach was accomplished

under cover of a fire from the boats of the flotilla.

The fort of Arabat was bombarded and taken. Meanwhile the large men-of-war

of the Allied Squadrons, outside the straits, made for

Soujoukkale and Anapa, strong places on the Circassian coast, which

at their approach were abandoned by their garrisons. These

operations were concluded by the second week in June, and

the result was thus summed up by Pelissier, in a letter to the

War Minister: "We have struck deep into the Russian

resources; their chief line of supply is cut. I did well to

concur in this expedition, so fertile in results. Confidence is

general, and I view with calm assurance the approach of the

final act." In fact, the expedition had fulfilled, in no slight

degree, the Emperor's policy of investment.

Meanwhile the clearance of the crowded Upland had

been effected. At daylight, on the 25th May, Canrobert, with

two Divisions, and cavalry and artillery, passed the Traktir

Bridge, drove the Russians from Tchorgoun, and destroyed

their camp and their barracks. The force then recrossed the

stream, and took position on its left bank, holding an armed

work at the bridge. Italy, having some time before joined the

alliance against Russia, had despatched General La Marmora,

with a small army of 15,000 men, including some cavalry and

artillery, to the Crimea. These troops now occupied ground on

the French right, across the road from Baidar. In rear of all a

large force of Turks from Eupatoria took up the same line of

heights across the valley of Balaklava which they had occupied

on the 25th of October. The land on which the Army was

encamped had at this time resumed its smiling aspect, except,

indeed, the ground between the Turks and Balaklava, where the

small paradise which had greeted us on our first arrival had

been completely destroyed. It had then been one large and well-

stored garden. Plums and apples grew overhead, the clustering

vines were thick with green and purple grapes, and between the

vineyards was a rich jungle of melons, pumpkins, tomatoes,

and cabbages. All this had given place to the grim features

of war. But elsewhere the grass had sprung up, mixed with

flowers in extraordinary variety and profusion ; the willows

again drooped their leaves over the Tchernaya ; even the field

of Inkerman resumed its green carpet, all the richer, perhaps,

for the battle, and turf like that of our south downs once more

covered the Upland. A most remarkable feature of the

southern coast of the Crimea is the rare beauty of the

colouring of its iron-bound coast. Those cliffs, so implacable

in the storms of winter, are dyed with the loveliest

rose-colours, pearly greys, yellows, dark reds, and rich

browns, with purple shadows, in the most effective

combinations. On a summit of these, in full view of the

Black Sea, stands the Monastery of St George, with its long

low ranges of building, its green domes and turrets, reared on solid

basements of masonry, white like the rest of the edifice. Here

the brotherhood, clad in black gowns, with tall cylindrical

caps, from which black veils descended behind, continued to

pray and chaunt; here, too, lived in peace some Russian

families, including that of the late commandant of Balaklava;

and here was established our telegraph station. Near this

was the site of an ancient temple of Diana; Cyclopean remains

exist there, the palace and gardens which contained the

famous Golden Fleece had looked from hence over the sea;

and it must have been in the valley below that "Medea gathered

the enchanted herbs, which did renew old Aeson."

There were tokens, too, of inhabitants compared with

whom Medea and ZEson are moderns. Across a gully, which

led to a cove used by our troops as a bathing-place, lay a ridge

which might have been the roof of a tunnel. But the many

footsteps at length wore away the soil of ages, and it was

apparent that a huge Saurian had been in some way swept

across the gully, and become fixed there; and it was his

skeleton, hidden even in Jason's time, that was now laid bare

to the view of British riflemen.

Crossing the valley of the Tchernaya, in grass and

flowers to the horses' knees, and ascending the green hillsides

of Kamara, beyond the Sardinian outposts, the explorer came

on expanses of tall coppice, with trees of larger growth, which

enclosed glades like those of a park. Here were some British

marines, whose lines had fallen in a place pleasant as the

meadows of Devon, in front of

which rose a wooded mountain, its craggy peaks breaking

through the verdure. A wood path, winding amid tall trees, led

to the next summit, which disclosed a magnificent landscape.

Below lay the valley of Baidar, stretching from the edge of

the sea-cliffs to the distant mountain range--a tract of

flowery meadows sprinkled with trees and groves. In the

midst of the valley stood, at some distance apart, two villages,

their roofs gleaming red through the surrounding trees ; but

no labourers, nor waggoners, nor cattle gave life to the scene,

nor had any corn been sown for this year's harvest. The

villages were not only deserted but, as some visitors had

ascertained, quite bare of all tokens of domestic life.

Turning back along the seacliffs, the silent, deserted,

beautiful region came to an end on reaching the fortified

ridge above Balaklava; here were the troops busied with their

camp duties, mules and buffaloes toiling with their loads; and

up the hills beyond Kadukoi, above the Turkish camp, the

bearded pashas, sitting in open, green tents, smoked their

long-stermmed pipes in that blissful calm which such matters

as wars and the peril of empires could not disturb.

Chapter XII: Succession of Conflicts

The officer who now took command of the French Army

was of a singularly strong and marked character. Its

distinguishing element was hardihood: hardihood in thought,

in dealing with others, and in the execution of hisprojects.

His comrades had formed an extraordinary estimate of his determination.

The officer who now took command of the French Army

was of a singularly strong and marked character. Its

distinguishing element was hardihood: hardihood in thought,

in dealing with others, and in the execution of hisprojects.

His comrades had formed an extraordinary estimate of his determination.

Back to War in the Crimea Table of Contents

Back to Crimean War Book List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com