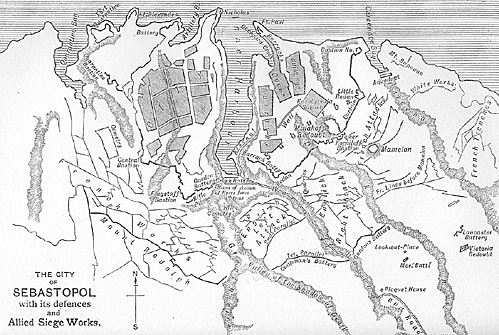

Jumbo Map: Sebastopol Siege Works (extremely slow: 488K)

The first

was the chief object, the second subsidiary. To establish

French troops and batteries on the Flagstaff Bastion,

and maintain them there, would have gone far to assure

the surrender or evacuation of the place; but in order to

effect this, it would be indispensable to hold the Redan

also, the close fire from which would otherwise render

the French operations very costly, or impossible.

But a great master of engineering science had been labouring on

these works with unceasing energy, and with

formidable effect. During the first winter months

Todleben had greatly extended and strengthened both

of these works, and also the Malakoff; and the Redan

was so completely dominated by the Malakoff that the capture

of this great work also had become an essential part of the

plan of attack. This had always been Burgoyne's opinion,

and he now supported it by arguing that the Malakoff was

more easy of approach than the other works; that the

possession of it, even if it should not, of itself, cause the

surrender of the place, would render the assault of the others

far less desperate, while guns placed on it would at once rid us

of the fire of the Russian ships. He represented,

moreover, that the Allies would thus best attain their real

object, which was not so much the capture of the town, as the

destruction of the docks, arsenal, and fleet. Since the battle of

Inkerman had given us possession of the heights overlooking

the harbour and the Careenage ravine, this plan had obviously

become more feasible, and Burgoyne had, in November and

December, urged officially his reasons for desiring that the

English should undertake the business, and that, as their

numbers were manifestly unequal to such an extension of duty

and work, the French should relieve them of the charge of

pushing forward and guarding the British Left Attack, the

batteries of which, however, would be held and fought by our

men as before. This would set free the Third Division to

perform the operations on Mount Inkerman. Immediately after

the battle of Inkerman the Allies had begun to strengthen the

ground there with works, one made by the French on the end

of the Fore Ridge, three by the English (one of them on

Shell Hill), to command the approaches, and to overlook the

bridge and causeway

over which Pauloff had advanced; and we had further made in

front of these a first parallel, and begun a second, as

approaches to the works between the Malakoff and the

harbour. When this proposal was finally considered at a

conference of chiefs at the beginning of February, the French

preferred to leave our Right and Left Attacks to us as before

and themselves to take charge of Mount Inkerman, except that

the British artillerymen and sailors already occupying our

works there, should so remain. It was so settled: Mount

Inkerman and the Victoria Ridge were given into the charge of

Bosquet's Corps; and at the same time the plan of advancing

on the Russian works from the Malakoff to the harbour, by

approaches from Mount Inkerman, and of pressing the attack,

not there especially, but along the whole Russian front, was

definitely adopted.

Allies Invigorated

Meanwhile the Allies had not been idle in the

trenches, even in the time of their direst trials. The first

parallel of the British Right Attack was completed, as well as

another in advance of it. A second parallel was carried across

the front of the Left Attack, and down the ravine on its right,

barring the Woronzoff road there. The French had sapped

up to within 180 yards of the Flagstaff Bastion, and now,

seeing the relations of mutual defence between it and the

Central Bastion, deemed it necessary to include the latter

also in their front of attack. Yet withal the business of the

siege proceeded of necessity very slowly. What transport the

Allies could muster was taken up with bringing food,

clothing, and shelter. In the trenches the

men stood generally ankle deep, sometimes knee deep, in

snow and liquid mud; except near the cliffs, and at a great

distance from the camps, the supply of fuel, in the form of

brushwood, which the plains afforded, had long since been

exhausted, and even the roots of the vines had been grubbed up

for cooking. And this want had become a hindrance to the

siege in another way.

"It is very unusual," says the Engineer journal, "to see

smoke from fires in trenches, yet this took place daily." The

cause of this was the want of fuel in the camps. The coffee

issued to the men was in the berry, which is the best form of it

when means for roasting are at hand, for wet does not injure it,

and it has, of course, far more flavour when freshly ground.

But when there was no fuel in camp, the men took the

green coffee with them to the trenches, ground it with

fragments of the enemy's shells, roasted it on their mess tins,

and boiled it in them, with fuel taken from the gabions and

fascines forming part of the works, and the parapets, of

course, suffered seriously from these depredations. The

troops, driven to these shifts, had become so few that the

French could only afford about 400 by day and 200 by night

for employment on the works, and the English a much smaller

number, while, according to the Engineer journal, the

trenches of our three attacks, the Right, the Left, and that on

Mount Inkerman, were at this time guarded only by 350 men,

and on one day in January by only 290 men, being about

one-twentieth of the number of the part of the garrison

opposed to them, and which might have attacked them.

On the other hand, the Russians having after Inkerman

abandoned the idea of using the field army for attacking the

Allied position, had begun to withdraw troops from it to

strengthen the garrison, and readjusted the supply between

them. They poured reinforcements into the place, till they

had not only made good the losses of the first weeks of

winter, but enabled its commander to employ on the works a

force varying, according to need, from 6000 to 10,000 men.

The guns, lying in the arsenal in thousands, and the

ammunition were easily brought to the batteries along the

paved streets.

Thus the fortress was immensely augmenting its

power of resistance just when we found the greatest difficulty

in holding our ground. Therefore, readers who have been

accustomed to hear the chiefs in Sebastopol and their troops

lauded as maintaining a struggle against unheard-of

difficulties, and as exhibiting extraordinary energy and powers

of resistance, may ask themselves how it was that an enemy

who possessed such enormously superior forces in men and

material, and who could at any time, during a period of

months, have directed on some selected point of the siege

works thousands of troops, that would have found only

hundreds to meet them, did not muster the courage for such an

enterprise when it promised deliverance to the fortress, and

ruin to their foes.

Yet they might perhaps have given the reason which

Canrobert had already pleaded for restraining enterprise, that

they were unwilling to set the great stake on a single cast, and

preferred to let delay and all its evils fight for them.

With this important exception, however, the Russians

showed great energy, even beyond the limits of a mere passive

defence, and every kind of work demanding skill and labour

they did well. Thus, Todleben developed a new feature in

trench warfare, which the range and accuracy of the rifle had

rendered possible. At night, parties issuing from the place

dug, on selected parts of the ground between the opposing

lines, rows of pits each fitted to hold a man, and having in

front a few sandbags, or sometimes a screen of stones, so

disposed as to protect his head, and to leave a small opening

through which to fire. At daybreak they began to harass

the guards of the trenches opposite, within easy range of

them. The French especially suffered by being thus

overlooked, and their proximity caused the enemy to adopt

this form of warfare chiefly in opposing them. To direct guns

on objects so small as these pits, and frequently at a great

distance from the batteries, seemed but a doubtful policy, and

they were therefore opposed by men, similarly covered by

sandbags, from the parapets. After a time, Todleben,

finding his idea so successful, expanded it; the rows of rifle

pits were connected, by trenches, in parts of which shelter was

given to continuous ranks of riflemen, and the defence being

thus pushed out in advance of the general line, wore the aspect

of besieging the beseigers. He had begun these

enterprises in November, greatly aggravating the cares of the

scanty defenders of the trenches. Beyond the advanced

trench of our Left Attack some of these pits had been placed,

screened by small stone walls, causing

great annoyance both to our people opposite and to the

French across the ravine, whose advanced works they partly

looked into.

It was on the night of the 20th November that a party of

the rifles was ordered to clear these pits, which were

supported by another row in rear. The occupants were driven

out after a sharp struggle, with losses on both sides, and a

working party made the spot tenable by our people--a service

so highly appreciated by our Allies that Canrobert passed a

warm encomium on it in general orders.

In November there also began, in the French attack

from Mount Rodolph, a war of mines and countermines. A

gallery was being driven towards the Flagstaff Bastion, when

it was detected and blown in by the enemy. A mine was,

however, placed in the gallery, far short of the position at

first destined for it, in order to break up the ground before

the bastion, and thus enable the French to effect a lodgment

there.

But this plan did not turn out happily; the watchful

engineer opposed to them proved himself a master also of

this subterranean warfare, and when the mine was exploded, it

was the Russians who succeeded in establishing themselves

on the crater.

It was on the 22d of February that the Russians

undertook an enterprise which marked an epoch in the siege,

and which was caused by another, the intention of which had

become apparent on the part of the Allies. In front of the

Malakoff, at about 500 yards from it, and on the same strip of

the plain, was a conical hill, of rather greater height,

and of such importance to either side which should

seize it that it would doubtless have been a main

object with us from the first but for our deficiency in

numbers. This was the hill which afterwards became

famous as the Mamelon.

To place it, as well as the

Malakoff and the intervening ground, under such a

cross fire as might assure its capture, two batteries

were prepared, one by the French, on a near spur

of Mount Inkerman, and one in the English Right

Attack. But their wary antagonist had not failed to

note and appreciate the design, and was now ready

with his counterstroke.

On the morning of the day named, the French, who the

day before had seen the Russian works end with the mouth of

the Careenage ravine, now beheld new works begun on, and in

extension of, a hill in front of them, being part of Mount

Inkerman itself, which the enemy had seized in the

course of the night, thus extending the front of the

fortress to new ground, and flanking the approaches

to the Malakoff and Mamelon; while the new work

was itself protected by so powerful a fire that the

French might well hesitate to attack it.

Night Attack

All the 23d the enemy were again at work on it. That

night, however, five French battalions, under General

Monet, issued from the trenches, and while two remained

halted in support, three advanced to the assault. This

step had been anticipated and provided for by the

Russians. Besides three battalions assigned to work

on and to defend the hill, four others, being an entire

regiment, were disposed for its defence, and now met the attack. They were supported by guns both from the

fortress and the ships, which were brought to bear on the

ground between the hill and the French trenches.

The combat lasted an hour; the French succeeded at one

time in entering the work, but were driven out by the strong

supports, and forced to retreat, bearing with them General

Monet, desperately wounded, and sustaining a loss of 270 men,

with nineteen officers, while the Russians lost 400.

Todleben credits the French troops on this occasion with

"a remarkable valour." This defeat was so far acknowledged

and accepted by the French that the enemy was thenceforth

left almost undisturbed to complete and arm his new work,

and a few nights later he began another on a hill to his own

left of it. These were in future known to the Allies as the

White Works from the chalky soil they stood in. Thus, having

completely abandoned Mount Inkerman after the battle, the

enemy had now returned to it in a fashion which showed that

he intended his occupation of it to be permanent. By this rare

display of sagacity and daring, Todleben immensely increased

the difficulty of the problem before the Allies.

At a conference of chiefs, on 6th March, Burgoyne urged

the French to attack these works as the indispensable

preliminary to progress on this part of the field; but the

proposal was put aside on the ground that, if captured, they

could not be held under the guns which the enemy could bring

to bear.

The two batteries, French and English, looking

towards the Mamelon were pushed steadily towards

completion, and on the 10th March the commanding French

engineer, Bizot, advised Canrobert to seize the hill that night.

Canrobert declined the enterprise, but Todleben settled the

question. On this same night the Russians seized it, and

morning saw the outline of a work crowning it.

The question of attacking it was now more urgent than

before. But Canrobert still found reasons against so decided a

course, and preferred to besiege it. Consequently, the French

opened a parallel against it on the Victoria Ridge, and the new

batteries were also directed on it. On the other hand, the

enemy held his ground, and not only completed and armed his

new work, but spread rifle pits, connected with trenches,

along its front and flanks.

Thus a very formidable element entered into the

problem of the siege. It has been already pointed out how

embarrassing to the Allies were the outposts the enemy had

placed, in October, in advance of their works, Here was a

tremendous aggravation of the infliction for not only did the

Mamelon cover what had hitherto been the objects of attack

in that quarter, but it looked into trenches of our Right Attack

hitherto secure from fire, and forbade, under heavy penalties,

its further approach towards the Redan.

The French had pushed their approaches so close to

the small works covering the Mamelon that they might be

expected presently to seize them, when, in the night of the

22d March, the enemy cast large bodies of troops on the

opposing lines. Between 5000 and 6000 men attacked the

French trenches before the Mamelon, and at

first penetrated into them, driving in the guards and working

parties. But their success ended there; the French showed so

firm a front that the attack collapsed, and the enemy fell back

and re-entered the fortress, after inflicting on their opponents

a loss of 600 men.

Simultaneously with the entry of the French works,

800 Russians moved out for an advance upon our Right Attack,

but were easily repulsed for the time. This attack had been

made on the part of the trenches next the Docks ravine. An

hour later another assault (which apparently ought to have

been in concert with the first) was made on the left portion of

the same trenches by Greek and other volunteers. Led by

an Albanian, in the dress of his country, they broke into the

parallel, where the leader, first shooting one of our officers,

discharged a pistol ineffectually at the magazine, and was then

killed himself The assailants moved along the trench from left

to right till the guards and working parties, having been got

together, met and drove them back upon the Redan.

At the same time with this last, another assault had

been directed, with Soo men, on the advanced trench of our

Left Attack, close to where the ridge was cut short by the

ravine, and penetrated to the third parallel, where they were

attacked by the nearest bodies of those guarding the trenches,

and driven back like the rest. In these fights the officer

commanding the guards of the Right Attack was wounded and

captured, as was the engineer of the Left Attack, with about

fifteen men, and a quantity of entrenching tools, dropped by

the working parties when they took up their arms. In all, we

lost seventy men. The enemy left about forty dead in front of our

Right Attack, ten killed and two wounded in the trenches of

the Left; and his losses, in all, that night were 1300 men.

If the Russians aimed, in this sortie, at establishing

themselves in the French lines, it was so far a failure. But the

object of such an enterprise is mostly to inflict hasty damage

and discouragement on the enemy, and to gain a temporary

facility for executing some of the defensive operations; and

on this ground the Russians might claim a certain success, for

in the following night they connected the pits in front of the

Mamelon by a trench, which their engineer extended to the

verge of the ravine. Thus he had succeeded in forming and

occupying, within eighty yards of the French, an entrenched

line, supported by, while it covered, the Mamelon.

A truce was agreed on for burying the slain, to begin

half-an-hour after noon on the 24th. White flags were then

raised over the Mamelon and the French and English works,

and many spectators streamed down the hillsides to the scene

of contest. The French burial parties advanced from their

trenches, and hundreds of Russians, some of them bearing

stretchers, came out from behind the Mamelon. The soldiers

of both armies intermingled on friendly terms. The Russians

looked dirty and shabby, but healthy and well fed. Between

these groups moved the burial parties, collecting the bodies

and conveying them within the lines on both sides. At

450 yards from the scene rose the Mamelon,

its parapet lined with spectators. Five hundred yards beyond

it, separated by a level space, stood the Malakoff, its ruined

tower surrounded by earthen batteries; and through the space

between it and the Redan appeared the best built portion of

the city, jutting out into the harbour, and near enough for the

streets, with people walking in them, the marks of ruin from

shot, the arrangement of the gardens, and the line of sunken

ships, to be plainly visible. About forty bodies were

removed from the front of the English Right Attack, among

them that of the Albanian leader, partially stripped, and

covered again with his white kilt and other drapery. In two

hours the business was over, the soldiers on both sides had

withdrawn within their lines, the flags were lowered, and the

fire went on as before.

This was the only considerable attempt as yet made

on the trenches, but small losses from fire occurred in them

almost daily and nightly. At one time the men killed had been

taken at night to the front of the works, and there buried, and a

strange experience fell in consequence on a young engineer,

destined to a place in the esteem of his country far beyond

that of any other soldier of these latter generations, Charles

Gordon. In carrying a new approach to the front, these

graves lay directly across it, and he described how the

working party had to cut their way straight through graves and

occupants, and how great was the difficulty he found in

keeping the men to their horrible task, which, however, was

duly completed. He had a brother, Enderby

Gordon, on the staff of the artillery, to whom he used to

relate his experiences; among others, of strolls he was in the

habit of taking at night far beyond our trenches, one of which

led him up close to the outside of the Russian works, so that

he could hear the voices of the men on the parapet.

A singularly ghastly incident of these burials took place

about this time. One night two men had carried the body of a

comrade, just slain, on to the open ground for interment, and

had finished digging the grave, and placing the body in it,

when, as they were about to fill it in, a shot from the enemy,

who had perhaps heard them at work, killed one of them. The

survivor laid his comrade's body beside the other, buried

both, and returned to the trench.

In the period to which this chapter relates several

events of military importance had occurred, to have

chronicled which, at their respective dates, would have

broken the narrative of the siege.

On the 6th December the troops which Liprandi had

established in the valley of Balaklava were withdrawn across

the Tchernaya, leaving only detachments of the three arms in

the villages of Kamara and Tchorgoun, and a field work with

guns to guard the bridge at Traktir. On the 30th

December a considerable French force advanced up the

valley, while the 42d Highlanders moved by the hills above,

swept the residue of the enemy over the stream, and shelled

the guns out of the bridge head, and the troops out of

Tchorgoun.

After destroying the Russian huts and forage, and

capturing their cattle and

sheep, the troops returned to their camps. Access was thus

once more gained to the Woronzoff road, and in time a good

road was made connecting it with Balaklava.

In January two French officers arrived in the Crimea,

both destined, though in entirely opposite ways, to exercise an

important influence on the course of the war. The Emperor

Napoleon, regarding the appointments already made to the

command of Corps and Divisions by Canrobert, under the

pressure of circumstances, as provisional merely, had

summoned General P61issier from his Government of Oran,

and placed him in charge of the ist Corps, that besieging the

lines before the town; and it will be seen how powerful was

the impelling element introduced with the presence of this

masterful spirit into the attack on the fortress. And, on the

27th of January, General Niel, the engineer who had just

conducted operations against Bomarsund, and who was

regarded as the military counsellor of the Emperor, arrived in

the Crimea on a special mission. The nature of this, kept

secret at the time, will appear in the next chapter; but he at

once expressed his ideas of the military situation. Regarding

it, from the engineer's point of view, as a siege, and what

should consequently follow the rules of a siege, one of which

was that a necessary step towards the capture of a fortress is

its investment, so he believed that all the efforts of the Allies

must be vain until they should have intercepted all

communication between Sebastopol and Menschikoff's army.

"Believe, Monsieur le Marechal," he wrote to the

Minister for War, " that nothing can be done without

investing," and with this opinion his language at the

conference was in unison.

And, no doubt, to have severed all communication with

the city must have been effectual in the end, if practicable ;

but the event showed that the measure was not indispensable.

That the Russians feared such a step was shown about this

time. Omar Pasha had been for some time assembling, at

Eupatoria, bodies of his Turks from the Danube. The town had

been surrounded with works of earth and loose stones by the

French officer at first left in charge of the place.

These, thrown forward to a salient in the centre, bent

round on both flanks to the sea. About 23,000 Turks and

thirty-four heavy guns were within these works, when the

Russians, alarmed for their communications with Perekop,

delivered an attack upon the place with a large force drawn

from Menschikoffs army, and said by Todleben to number

19000 infantry, with a strong cavalry and numerous artillery.

Both flanks of the works of the place were defended by a

French steamer, a Turkish, and four English steamers lying in the bay.

On the 16th February the Russians appeared before

the place. They spent the night in throwing up cover for their

batteries, and by morning had seventy-six guns, twenty-four

of them of heavy calibre, ready to open at from 600 to 800

yards from the works. At daybreak the cannonade began, and

when the fire of the place seemed to be overcome, three

columns of attack, supported by field batteries, advanced on

the centre and

flanks of the defensive line. Two of these were stopped by the

fire of the steamers and of the place; the third, on the right

front of the Turkish line, finding cover in the walls of the

cemeteries there, assembled under their shelter, and advanced

more than once almost to the ditch, but were easily repulsed;

and with the last attempt in this quarter the enterprise came to

an end, and the Russians drew off at once towards the

interior. They lost 769 killed and wounded; the garrison, 387.

Even had they carried the works, it is difficult to

perceive how they could have proposed to maintain

themselves in the place, under the fire of the ships. It was

probably his experience of what this fire could effect, and

against which no return could be made, that so convinced the

Russian commander of the hopelessness of the enterprise, as

to render the assault weak and futile in comparison with his

forces. No further attempt was made on Eupatoria during

the war. This failure, following on the others, was visited on

Menschikoff by withdrawing him from the command of the

Forces in the Crimea, in which he was succeeded by

Gortschakoff.

Port Blockade

In February the Russians, finding that the line of

sunken vessels across the harbour had been much broken up

by the waves, sank six more, in a line inside the other; and on

the 6th March an English battery on Mount Inkerman brought

some guns, with hot shot, to bear on two warships in

Careening Creek which had greatly annoyed the French, and

drove them, one much damaged, round a sheltering point.

An important figure also disappeared from the

councils of the Allies. In February the new Government, in

order to appease a vague desire (part of the general

discontent and impatience agitating the country) for any

change which might quicken the siege operations, had

decided on the recall of Sir John Burgoyne, and General

Harry Jones had in that month arrived in the Crimea as his

successor. But Lord Raglan desired to keep his old

counsellor by his side at a time when so many important

engineering questions were pending; he continued to be

present at the conferences, and to issue plans and

suggestions, till the third week in March, when he departed

for England.

The defence of the place lost a redoubted champion,

on the 19th March, when Admiral Istomine was killed in the

Mamelon. He was buried by the side of Korniloff, in a tomb

made by Admiral Nakimoff with the intention of lying there

himself, but he now ceded the place to his illustrious

comrade.

With the advance of spring the situation of the Allies

(though the siege seemed as far as ever from its end) had

become greatly more favourable. Not only had the climate

grown mild, not only were the plains, clad in renewed

verdure, once more easy to traverse, but the time of

privations was long past, and almost seemed a bad dream; the

men were well fed, well clothed, and well housed; the horses

had been restored to condition and duly recruited in numbers;

a city of huts, like those to be seen at Aldershot, spread over

the Upland; the railway brought vast stores from Balaklava to

the plateau, from whence they were forwarded to the dep6ts of the camps

by a growing land transport. Colonel MacMurdo, armed with

independent purchasing powers, had come out to superintend

the formation of that transport corps, manned both by old

soldiers and recruits specially raised, and had so used his

opportunities that horses, trained drivers, escorts, and

vehicles, were being rapidly assembled and organised.

All this demanded a great outlay, insomuch that on one of

the Colonel's many large requisitions the Secretary to the

Treasury, Sir Charles Trevelyan, had written: "Colonel

MacMurdo must limit his expenditure."

When the paper returned to the Colonel with these words,

he wrote below them: "When Sir Charles Trevelyan limits the

war, I will limit my expenditure." Equal improvement marked

the condition of the French, and vast stores of guns had been

brought up and mounted in the batteries early in April, with,

for the English ordnance, a supply of 500 rounds for each

gun, and 300 for each mortar. We had thus accumulated the

means of a sustained and tremendous cannonade, in which 378

French guns would take part, and 123 English, proportionate

to the extent of trenches and batteries occupied by each; but

the English guns were for the most part so much more

powerful that the difference in weight of metal was not great.

On these, 466 Russian guns (out of nearly 1000 on the

works) could be brought to bear. And it was certainly

expected, as before, on both sides that, as soon as the

cannonade should have produced its effect, the Allies would

be prepared to assault. So all three armies

believed; so Lord Raglan believed. But, as has been said,

General Niel, the counsellor of the Emperor, had no faith in

any measures which did not include an investment. It had been

evident that some influence had been at work which had held

back the French troops from assaulting many parts of the

defences which seemed to offer fair chances of capture; and

circumstances, afterwards found to have existed, seem to

show that the French commander did not at this time intend to

push matters beyond a cannonade.

On Easter Sunday, the 8th April, orders were given for

opening fire next morning. The mortars, absent on the former

occasion, were now a prominent feature in the attacking

batteries, placed behind lofty and solid parapets, and hurling

their great missiles high into the air, to drop thence into an

enemy's work, and there explode. The various character of the

soil of the plains must now once more be noted, as it very

seriously affected the siege operations carried on in it.

On the slopes of Mount Inkerman, and in our Right and

Left attacks, especially the right, the soil was thin, the rock

lay immediately below, and the workmen painfully scooped an

often insufficient cover, frequently by dint of blasting; and the

want of earth for parapets was in many cases supplied by

sandbags filled elsewhere. But on Mount Rodolph, and to

its left, the soil was favourable, easily trenched, and supplying

earth in quantity sufficient to rear the parapets high, and

thicken them to solidity; and thus the French had been able on

that side to sap up and push their trenches to within 16o yards

of the Flagstaff Bastion, while our fire was still mainly delivered

(though some mortar batteries had been formed in advance),

as in October, from the batteries first constructed, Gordon's

and Chapman's.

When the sun should have appeared next morning, a

dense mist covered the plains. It lifted a little, and at half-past

six our guns, as they caught sight of the opposing batteries,

opened fire, and the French soon followed. The Russians were

so completely unprepared that it was twenty minutes before

they began to reply. A strong wind swept volumes of the

smoke from the Allied trenches over the Russian works, and

must have added greatly to the difficulties of the men who

worked the guns there. They were slack in replying; the guns

in the redoubted Mamelon fired slowly, so did those of the

Malakoff, as if insufficiently manned, though really owing to

dearth of powder; and a face of the Redan was silenced.

On the other hand, the French breached the salient of the

Central Bastion, and inflicted immense damage and loss of

men on the Flagstaff Bastion. When the sun went down, the

fire of the Allied guns ceased. Not so those of their mortars,

which did not depend on keeping sight of their object, and all

night the great shells climbed the sky, and descended on their

prey. Nevertheless, the works were again in a condition of

defence next morning. On this second day the White Works

were reduced to silence and ruin. On the 11th the English

and French batteries directed on the Mamelon extinguished

its fire, and the Malakoff scarcely fired at all, while the

Flagstaff Bastion had been again and again reduced to the direst extremity.

Therefore, in momentary expectation of an assault, the

Russian troops were kept at hand in, or close to, the lines of

defence, and as a consequence suffered heavily. They were

subjected to terrible trials, from which the Allies were

exempt, for the hurricane of iron which, besides ruining

works, dismounting guns, and exploding magazines, swept

without intermission through the whole interior space of the

fortress, where it had already razed the barracks and public

buildings of the suburb to the ground, and choked the streets

of the city with destroyed masonry, could not but tell heavily

on uncovered troops.

Remarkable Incident

A remarkable incident occurred at this time. In the

trenches on the furthest point of our Left Attack, on the verge

of the ravine, two batteries had been constructed, but not

armed. On the night of the 11th guns were conveyed to one of

them, across the open ground, and these on the following day

were placed on their platforms. These batteries were on much

lower ground than the Redan and the Barrack Battery on the

one side, and the Garden Batteries and Flagstaff Bastion on

the other. Nevertheless, this battery of four guns opened

fire on the 13th on its formidable opponents. From their

commanding heights, they very soon concentrated on it the

overwhelming fire of about twenty heavy guns. The contest

was hopeless, but it was maintained. For five hours the

English guns, gradually reduced to one that remained in a

condition to fire, replied, not without effect. Then, this last

gun disabled, nearly all

the gunners struck down, the parapets swept away, the

remnant of men were at length withdrawn. Out of forty-seven

men, forty-four had been killed or wounded.

In the night the damage was repaired, and the four

guns were put once more in fighting condition. And the

battery no longer fought singly in the front line; its neighbour

was armed with six guns. On the 14th they opened and brought

on themselves a terrible stress of fire. All day (with one

relief), and even into the night, they maintained the fight,

when, with many guns disabled, many men killed and

wounded, and the parapets once more knocked into shapeless

heaps, they were withdrawn from the works, which were not

again manned. This episode, while it did little (that little,

perhaps, in the way of attracting shot from the enemy which

would otherwise have been directed on other points) towards

a general result, enabled Todleben to score a substantial and

indisputable success in the midst of his calamities elsewhere.

Yet these English gunners had not fought quite in vain; they

are still remembered as having set a rare example of valorous

devotion.

Ten days did the terrific storm of iron hail endure;

ten days did the Russian reliefs, holding themselves ready to

repel attack, meet wounds and death with a constancy which

was of necessity altogether passive. On the 19th they saw

the fire of the Allies decline, and settle into its more ordinary

rate; they saw, too, that the sappers were again at work with

their approaches, and reading in this the signs of a resumption

of the siege, and the abandonment of the policy of assault, they once more

withdrew their sorely harassed infantry to places of shelter

and repose. Then they began to reckon their losses, which

amounted for the ten days, in killed and wounded, to more

than 6000 men. The French lost, in killed and disabled, 1585

men; the English, 265.

During these days and nights the great ballroom of the

assembly rooms in Sebastopol was crowded with the wounded

incessantly arriving on stretchers. The floor was half-an-inch

deep in coagulated blood. In an adjoining room, set apart for

operations, the blood ran from three tables where the

wounded were laid, and the severed limbs lay heaped in tubs.

Outside, fresh arrivals thronged the square, on their blood-

steeped stretchers, their cries and lamentations mingling with

the roar of shells bursting close by. Many more were

borne to the cellars of the sea-forts; and those capable of

removal to the north side were conveyed thither to permanent

hospitals. In a church near the harbour the mournful chaunt of

the office for the dead resounded continually through the

open doors of the building. It was there that the funeral

service was celebrated of officers dead on the field of

honour. Such is the picture drawn by eye-witnesses of what

was seen of the results of the conflict in the more remote

parts of the city. Nor was the change to the country outside

the fortress much for the better. A Russian, passing from

thence to St Petersburgh, there testified that the route from

Sebastopol to Simpheropol was so encumbered with dead

bodies, dead horses, and dead cattle, that the whole line was infected

with pestilential vapours, and, being impassable for vehicles,

could only be traversed on horseback.

All these days great impatience had prevailed in the

English camp. It was asked why the cannonade had been

begun if not to be followed to its legitimate conclusion. The

key to the mystery is to be found in the following chapter.

Chapter X: Important Events Elsewhere

It has been said that the plan of attack, on the 17th

October, was that the French should assault the Flagstaff

Bastion, and the English the Redan.

It has been said that the plan of attack, on the 17th

October, was that the French should assault the Flagstaff

Bastion, and the English the Redan.

Back to War in the Crimea Table of Contents

Back to Crimean War Book List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com