The return of Commodore Dale from the Mediterranean, and the reports which he brought of the continued aggressions and insolence of the Barbary powers, made a very marked change in the temper of the people of the United States. Early in 1802 Congress passed laws, which, though not in form a formal declaration of war, yet permitted the vigorous prosecution of hostilities against Tripoli, Algiers, or any other of the Barbary powers. A squadron was immediately ordered into commission for the purpose of chastising the corsairs, and was put under the command of Commodore Morris. The vessels detailed for this service were the " Chesapeake," thirty-eight "Constellation," thirty-eight; "New York," thirty-six; "John Adams," twenty-eight; "Adams," twenty-eight ; and "Enterprise," twelve. Some months were occupied in getting the vessels into condition for sea; and while the "Enterprise" started in February for the Mediterranean, it was not until September that the last ship of the squadron followed her. It will be remembered that the "Philadelphia" and "Essex," of Dale's squadron, had been left in the Mediterranean; and as the "Boston," twenty-eight, had been ordered to cruise in those waters after carrying United States Minister Livingstone to France, the power of the Western Republic was well supported before the coast-line of Barbary.

The "Enterprise" and the " Constellation " were the first of the squadron to reach the Mediterranean, and they straightway proceeded to Tripoli to begin the blockade of that port. One day, while the 11 Constellation " was lying at anchor some miles from the town, the lookout reported that a number of small craft were stealing along, close in shore, and evidently trying to sneak into the harbor.

Immediately the anchor was raised, and the frigate set out in pursuit. The strangers proved to be a number of Tripolitan gun-boats, and for a time it seemed as though they would be cut off by the swift-sailing frigate. As they came within range. the " Constellation " opened a rapid and well-directed fire, which soon drove the gun-boats to protected coves and inlets in the shore. The Americans then lowered their boats with the intention of engaging the enemy alongshore, but at this moment a large body of cavalry came galloping out from town to the rescue. The Yankees, therefore, returned to their ship, and, after firing a few broadsides at the cavalry, sailed away.

Thereafter, for nearly a year, the record of the American squadron in the Mediterranean was uneventful. Commodore Morris showed little disposition to push matters to an issue, and confined his operations to sailing from port to port, and instituting brief and imperfect blockades.

Surprise Explosion

Surprise Explosion

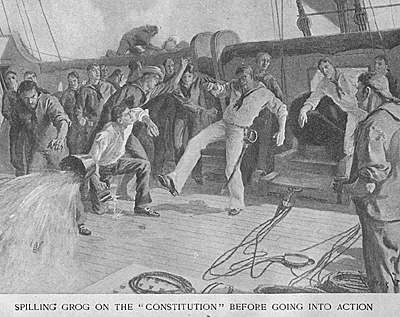

In April, 1803, the squadron narrowly escaped being seriously weakened by the loss of the "New York." It was off Malta on her way to Tripoli in company with the "John Adams" and the "Enterprise." The drums had just beat to grog; and the sailors, tin cup in hand, were standing in a line on the main deck waiting their turns at the around the tub. Suddenly a loud explosion was heard, and the lower part of the ship was filled with smoke.

"The magazine is on fire," was the appalling cry; and for a moment confusion reigned everywhere. All knew that the explosion must have been near the magazine. There was no one to command, for at the grog hour the sailors are left to their own occupations. So the confusion spread, and there seemed to be grave danger of a panic, when Capt. Chauncey came on deck. A drummer passed hurriedly by him.

"Drummer, beat to quarters!" was the quick, sharp command of the captain. The drummer stopped short, and in a moment the resonant roll of the drum rose above the shouts and the tramping of feet. As the well-known call rose on the air, the men regained their self-control, and went quietly to their stations at the guns, as though preparing to give battle to an enemy.

When order had been restored, Capt. Chauncey commanded the boats to be lowered ; but the effect of this was to arouse the panic again. The people rushed from the guns, and crowded out upon the bowsprit, the spritsail-yard, and the knightheads. Some leaped into the sea, and swam for the nearest vessel. All strove to get as far from the magazine as possible. This poltroonery disgusted Chauncey.

"Volunteers, follow me," he cried. "Remember, lads, it's just as well to be blown through three decks as one."

So saying he plunged down the smoky hatchway, followed by Lieut, David Porter and some other officers. Blinded and almost stifled by the smoke, they groped their way to the seat of the danger. With wet blankets, and buckets of water, they began to fight the flames. As their efforts began to meet with success, one of the officers went on deck, and succeeded in rallying the men, and forming two lines of water-carriers. After two hours' hard work, the ship was saved.

The explosion was a serious one, many of the bulkheads having been blown down, and nineteen officers and men seriously injured, of whom fourteen died. It came near leading to a still more serious blunder; for, when the flames broke out, the quartermaster was ordered to hoist the signal, " A fire on board." In his trepidation he mistook the signal, and announced, "A mutiny on board."

Seeing this, Capt. Rodgers of the "John Adams" beat his crew to quarters, and with shotted guns and open ports took up a raking position astern of the "New York," ready to quell the supposed mutiny. Luckily he discovered his error without causing loss of life.

For a month after this incident, the ships were detained at Malta making repairs ; but, near the end of May, the "John Adams," "Adams," "New York," and "Enterprise" took up the blockade of Tripoli. One afternoon a number of merchant vessels succeeded in evading the blockaders, and though cut off from the chief harbor of the town, yet took refuge in the port of Old Tripoli. They were small lanteen-rigged feluccas of light draught ; and they threaded the narrow channels, and skimmed over Shoals whither the heavy men-of-war could not hope to follow them.

Scarcely had they reached the shore when preparations were made for their defence against any cutting-out party the Americans might send for their capture. On the shore near the spot where the feluccas were beached, stood a heavy stone building, which was taken possession of by a party of troops hastily despatched from the city. The feluccas were laden with wheat, packed in sacks; and these sacks were taken ashore in great numbers, and piled up on either side of the great building so as to form breastworks. So well were the works planned, that they formed an almost impregnable fortress. Behind its walls the Tripolitans stood ready to defend their stranded vessels.

That night Lieut. Porter took a light boat, and carefully reconnoitred the position of the enemy. He was discovered, and driven away by a heavy fire of musketry, but not before he had taken the bearings of the feluccas and their defences. The next morning he volunteered to go in and destroy the boats, and, having obtained permission, Set Out, accompanied by Lieut. James Lawrence and a strong party of sailors. There was no attempt at concealment or surprise. The Americans pushed boldly forward, in the teeth of a heavy fire from the Tripolitans.

No attempt was made to return the fire, for the enemy was securely posted behind his ramparts. The Yankees could only bend to their oars and press forward with all possible speed. At last the beach was reached, and boats-prows grated upon the pebbly sand. Quickly the jackics leaped from their places; and while some engaged the Tripolitans, others, torch in hand, clambered upon the feluccas, and set fire to the woodwork and the tarred cordage. When the flames had gained some headway, the incendiaries returned to their boats, and made for the squadron again, feeling confident that the Tripolitans could do nothing to arrest the conflagration.

But they had underestimated the courage of the barbarians; for no sooner had the boats pushed off, than the Tripolitans rushed down to the shore, and strained every muscle for the preservation of their ships. The men-of-war rained grape-shot upon them; but they persevered, and before Porter and his followers regained their ships, the triumphant cries of the Tripolitans gave notice the flames were extinguished. Porter had been severely wounded in the thigh, and twelve or fifteen of his men had been killed or wounded ; so that the failure of the expedition to fully accomplish its purpose was bitterly lamented. The loss of the enemy was never definitely ascertained, though several were seen to fall during the conflict.

On both sides the most conspicuous gallantry was shown ; the fighting was at times almost hand to hand, and once, embarrassed by the lack of ammunition, the Tripolitans seized heavy stones, and hurled them down upon their assailants.

For some weeks after this occurrence, no conflict took place between the belligerents. Commodore Morris, after vainly trying to negotiate a peace with Tripoli, sailed away to Malta, leaving the "John Adams" and the "Adams" to blockade the harbor. To them soon returned the Enterprise, and the three vessels soon after robbed the Bey of his largest corsair.

On the night of the 21st of June, an unusual commotion about the harbor led the Americans to suspect that an attempt was being made to run the blockade. A strict watch was kept ; and, before morning, the Enterprise discovered a large cruiser sneaking along the coast toward the harbor's mouth. The Tripolitan was heavy enough to have blown the Yankee schooner out of the water; but, instead of engaging her, she retreated to a small cove, and took up a favorable position for action. Signals from the Enterprise soon brought the other United States vessels to the spot while in response to rockets and signal guns from the corsair, a large body of Tripolitan cavalry came galloping down the beach, and a detachment of nine gunboats came to the assistance of the beleaguered craft.

No time was lost in maneuvering. Taking up a position within pointblank range, the "John Adams" and the "Enterprise" opened fire on the enemy, who returned it with no less spirit. For forty-five minutes the cannonade was unabated. The shot of the American gunners were seen to hull the enemy repeatedly, and at last the Tripolitans began to desert their ship. Over the rail and through the open ports the panic-stricken corsairs dropped into the water. The shot of the Yankees had made the ship's deck too hot a spot for the Tripolitans, and they fled with great alacrity. When the last had left the ship, the "John Adams" prepared to send boats to take possession of the prize.

But at this moment a boat-load of Tripolitans returned to the corsair; and the Americans, thinking they were rallying, began again their cannonade. Five minutes later, while the boat's-crew was still on the Tripolitan ship, she blew up. The watchers heard a sudden deafening roar; saw a volcanic burst of smoke; saw rising high above the smoke the main and mizzen masts of the shattered vessel, with the yards, rigging, and hamper attached. When the smoke cleared away, only a shapeless hulk occupied the place where the proud corsair had so recently floated. What caused the explosion, cannot be told. Were it not for the fact that many of the Tripolitans were blown up with the ship, it might be thought that she had been destroyed by her own people.

Preble Takes Command

After this encounter, the three United States vessels proceeded to Malta. Here Commodore Morris found orders for his recall, and he returned to the United States in the "Adams." In his place Commodore Preble had been chosen to command the naval forces ; and that officer, with the "Constitution," forty-four, arrived in the Mediterranean in September, 1802. Following him at brief intervals came the other vessels of his squadron, the "Vixen" twelve, "Siren" sixteen, and "Argus" sixteen; the "Philadelphia" thirty-eight, and the "Nautilus" twelve, having reached the Mediterranean before the commodore.

Three of these vessels were commanded by young officers, destined to win enduring fame in the ensuing war -- Stephen Decatur, William Bainbridge, and Richard Somers.

Before the last vessel of this fleet reached the Mediterranean, a disaster had befallen one of the foremost vessels, which cost the United States a good man-of-war, and forced a ship's crew of Yankee seamen to pass two years of their lives in the cells of a Tripolitan fortress. This vessel was the "Philadelphia," Capt. Bainbridge. She had reached the Mediterranean in the latter part of August, and signalled her arrival by overhauling and capturing the cruiser "Meshboha," belonging to the emperor of Morocco. With the cruiser was a small brig, which proved to be an American merchantman ; and in her hold were found the captain and seven men, tied hand and foot. Morocco was then ostensibly on friendly terms with the United States, and Bainbridge demanded of the captain of the cruiser by what right he had captured an American vessel. To this the Moor returned, that he had done so, anticipating a war which had not yet been declared.

"Then, sir," said Bainbridge sternly, "I must consider you as a pirate and shall treat you as such. I am going on deck for fifteen minutes. If, when I return, you can show me no authority for your depredations upon American commerce, I shall hang you at the yard-arm."

So saying Bainbridge left the cabin. In fifteen minutes he returned, and, throwing the cabin doors open, stepped in with a file of marines at his heels. In his hand he held his watch, and he cast upon the Moor a look of stern inquiry. Not a word was said, but the prisoner understood the dread import of that glance.

Nervously he began to unbutton the voluminous waistcoats which encircled his body, and from an inner pocket of the fifth drew forth a folded paper. It was a commission directing him to make prizes of all American craft that might come in his path. No more complete evidence of the treachery of Morocco could be desired. Bainbridge sent the paper to Commodore Preble, and, after stopping at Gibraltar a day or two, proceeded to his assigned position off the harbor of Tripoli.

In the latter part of October, the lookout on the "Philadelphia " spied a vessel running into the harbor, and the frigate straightway set out in chase. The fugitive showed a clean pair of heels; and as the shots from the bow-chasers failed to take effect, and the water was continually shoaling before the frigate's bow, the helm was put hard down, and the frigate began to come about. But just at that moment she ran upon a shelving rock, and in an instant was hard and fast aground.

The Americans were then in a most dangerous predicament. The sound of the firing had drawn a swarm of gun-boats out of the harbor of Tripoli, and they were fast bearing down upon the helpless frigate. Every possible expedient was tried for the release of the ship, but to no avail. At last the gunboats, discovering her helpless condition, crowded so thick about her that there was no course open but to strike. And so, after flooding the magazine, throwing overboard all the small-arms, and, knocking holes in the bottom of the ship, Bainbridge reluctantly surrendered.

Hardly had the flag touched the deck, when the gun-boats were alongside. If the Americans expected civilized treatment, they were sadly mistaken, for an undiscipline d rabble came swarming over the taffrail. Lockers and chests were broken open, store-rooms ransacked, officers and men stripped of all the articles of finery they were wearing. It was a scene of unbridled pillage, in which the Tripolitan officers were as active as their men.

An officer being held fast in the grasp of two of the Tripolitans, a third would ransack his pockets, and strip him of any property they might covet. Swords, watches, jewels, and money were promptly confiscated by the captors; and they even ripped the epaulets from the shoulders of the officers' uniforms. No resistance was made, until one of the pilferers tried to tear from Bainbridge an ivory miniature of his young and beautiful wife. Wresting himself free, the captain knocked down the vandal, and made so determined a resistance that his despoilers allowed him to keep the picture.

When all the portable property was in the hands of the victors, the Americans were loaded into boats, and taken ashore. It was then late at night; but the captives were marched through the streets to the palace of the Bashaw, and exhibited to that functionary. After expressing great satisfaction at the capture, the Bashaw ordered the sailors thrown into prison, while the officers remained that night as his guests. He entertained them with an excellent supper, but the next morning they were shown to the gloomy prison apartments that were destined to be their home until the end of the war. Of their life there we shall have more to say hereafter.

While this disaster had befallen the American cause before Tripoli, Commodore Preble in the flagship "Constitution," accompanied by the "Nautilus," had reached Gibraltar. There he found Commodore Rodgers, whom he was to relieve, with the "New York " and the "John Adams." Hardly had the commodore arrived, when the case of the captured Morocco ship "Meshboha" was brought to his attention; and he straightway went to Tangier to request the emperor to define his position with regard to the United States. Though the time of Commodore Rodgers on the Mediterranean station had expired, he consented to accompany Preble to Tangier; and the combined squadrons of the two commodores had so great an effect upon the emperor, that he speedily concluded a treaty. Commodore Rodgers then sailed for the United States, and Preble began his preparations for an activc prosecution of the war with Tripoli.

It was on the 31st of October that the "Philadelphia" fell into the hands of the Tripolitans, but it was not until Nov. 27 that the news of the disaster reached Commodore Preble and the other officers of the squadron. Shortly after the receipt of the news, the commodorc proceeded with his flagship, accompanied by the "Enterprise," to Tripoli, to renew the blockade which had been broken by the loss of the "Philadelphia."

War With Tripoli

It was indeed high time that some life should be infused into the war with Tripoli. Commodore Dale had been sent to the Mediterranean with instructions that tied him hand and foot. Morris, who followed him, was granted more discretion by Congress, but had not been given the proper force. Now that Preble had arrived with a sufficient fleet, warlike instructions, and a reputation for dash unexcelled by that of any officer in the navy, the blue-jackets looked for some active service. Foreign nation, were beginning to speak scornfully of the harmless antics of the United States fleet in the Mediterranean, and the younger American officers had fought more than one duel with foreigners to uphold the honor of the American service. They now looked to Preble to give them a little active service.

An incident which occurred shortly after the arrival of the "Constitution" in the Bay of Gibraltar convinced the American officers that their commodore had plenty of fire and determination in his character.

One night the lookouts reported a large vessel alongside, and the hail from the "Constitution" brought only a counter-hail from the stranger. Both vessels continued to hail without any answer being returned, when Preble came on deck. Taking the trumpet from the hand of the quartermaster, he shouted,

"I now hail you for the last time. If you do not answer, I'll fire, a shot into you."

"If you fire, I'll return a broadside," was the reply.

"I'd like to see you do it. I now hail you for an answer. What ship is that?"

"This is H.B.M. ship Donegal, eighty-four; Sir Richard Strachan, an English commodore. Send a boat aboard."

"This is the United States ship 'Constitution,' forty-four," answered Preble, in high dudgeon; "Edward Preble, an American commodore; and I'll be damned I send a boat on board of any ship. Blow your matches, boys."

The Englishman saw a conflict coming, and sent a boat aboard with profuse apologies. She was really the frigate "Maidstone," but being in no condition for immediate battle had prolonged the hailing in order to make needed preparations.

On the 23d of December, while the "Constitution" and "Enterprise" were blockading Tripoli, the latter vessel overhauled and captured the ketch "Mastico," freighted with female slaves that were being sent by the Bashaw of Tripoli to the Porter as a gift. The capture in itself was unimportant, save for the use made of the ketch later.

The vessels of the blockading squadron, from their station outside the bar, could see the captured " Philadelphia " riding lightly at her moorings under the guns of the Tripolitan batteries. Her captors had carefully repaired the injuries the Americans had inflicted upon the vessel before surrendering. Her foremast was again in place, the holes in her bottom were plugged, the scars of battle were effaced, and she rode at anchor as pretty a frigate is ever delighted the eye of a tar.

Secret Messages

From his captivity Bainbridge had written letters to Commodore Preble, with postscripts written in lemon-juice, and illegible save when the sheet of paper was exposed to the heat. In these postscripts he urged the destruction of the "Philadelphia." Lieut. Stephen Decatur, in command of the "Enterprise," eagerly seconded these proposals, and proposed to cut into the port with the "Enterprise," and undertake the destruction of the captured ship. Lieut.-Commander Stewart of the "Nautilus" made the same proposition ; but Preble rejected both, not wishing to imperil a man-of-war on so hazardous an adventure.

The commodore, however, had a project of his own which he if communicated to Decatur, and in which that adventurous sailor heartily joined. This plan was to convert the captured ketch into a man-of-war, man her with volunteers, "and with her attempt the perilous adventure of the destruction of the "Philadelphia."

The project once broached was quickly carried into effect. The ketch was taken into the service, and named the "Intrepid." News of the expedition spread throughout the squadron, and many officers eagerly volunteered their services.

When the time was near at hand, Decatur called the crew of the Enterprise together, told them of the plan of the proposed expedition, pointed out its dangers, and called for volunteers. Every man and boy on the vessel stepped forward, and begged to be taken. Decatur chose sixty-two picked men, and was about to leave the deck, when his steps were arrested by a young boy who begged hard to be taken.

"Why do you want to go, Jack?" asked the commodore.

"Well, sir," said Jack, "you see, I'd kinder like to see the country."

The oddity of the boy's reason struck Decatur's fancy, and he told Jack to report with the rest.

Night Attack

On the night of Feb. 3, 1804, the "Intrepid," accompanied by the "Siren," parted company with the rest of the fleet, and made for Tripoli. The voyage was stormy and fatiguing. More than seventy men were cooped up in the little ketch, which had quarters scarcely for a score. The provisions which had been put aboard were in bad condition, so that after the second day they had only bread and water upon which to live. When they had reached the entrance to the harbor of Tripoli, they were driven back by the fury of the gale, and forced to take shelter in a neighboring cove. There they remained until the 15th, repairing, damages, and completing their preparations for the attack.

The weather having moderated, the two vessels left their place of, concealment, and shaped their course for Tripoli. On the way, Decatur gave his forces careful instructions as to the method of attack. The Americans were divided into several boarding parties, each with its own officer and work. One party was to keep possession of the upper deck, another was to carry the gun-deck, a third should drive the enemy from the steerage, and so on. All were to carry pistols in their belts; but the fighting, as far as possible, was to be done with cutlasses, so that no noise might alarm the enemy in the batteries, and the vessels in the port. One party was to hover near the "Philadelphia" in a light boat, and kill all Tripolitans who might try to escape to the shore by swimming. The watchword for the night was "Philadelphia."

About noon, the " Intrepid " came in sight of the towers of Tripoli. Both the ketch and the "Siren" had been so disguised that the enemy could not recognize them, and they therefore stood boldly for the harbor. As the wind was fresh, Decatur saw that he was likely to make port before night; and he therefore dragged a cable and a number of buckets astern to lessen his speed, fearing to take in sail, lest the suspicions of the enemy should be aroused.

When within about five miles of the town, the "Philadelphia" became visible. She floated lightly at her anchorage under the guns of two heavy batteries. Behind her lay moored two Tripolitan cruisers, and near by was a fleet of gunboats. It was a powerful stronghold into which the Yankee blue-jackets were about to carry the torch.

About ten o'clock, the adventurers reached the harbor's mouth. The wind had fallen so that the ketch was wafted slowly along over an almost glassy sea. The "Siren" took up a position in the offing, while the "Intrepid," with her devoted crew, steered straight for the frigate. A new moon hung in the sky. From the city arose the soft low murmur of the night. In the fleet all was still.

On the decks of the "Intrepid" but twelve men were visible. The rest lay flat on the deck, in the shadow of the bulwarks or weather-boards. Her course was laid straight for the bow of the frigate, which she was to foul. When within a short distance, a hail came from the "Philadelphia." In response, the pilot of the ketch answered, that the ketch was a coaster from Malta, that she had lost her anchors in the late gale, and had been nearly wrecked, and that she now asked permission to ride by the frigate during the night.

The people on the frigate were wholly deceived, and sent out ropes to the ketch, allowing one of the boats of the "Intrepid" to make a line fast to the frigate. The ends of the ropes on the ketch were passed to the hidden men, who pulled lustily upon them, thus bringing the little craft alongside the frigate. But, as she came into clearer view, the suspicions of the Tripolitans were aroused ; and when at last the anchors of the "Intrepid" were seen hanging in their places at the cat-heads, the Tripolitans cried out that they had been deceived, and warned the strano-ers to keep off. At the same moment the cry, "Americanos! Americanos!" rang through the ship, and the alarm was given.

By this time the ketch was fast to the frigate. "Follow me, lads," cried Decatur, and sprang for the chain-plates of the "Philadelphia." Clinging there, he renewed his order to board; and the men sprang to their feet, and were soon clambering on board the frigate. Lieut. Morris first trod the deck of the "Philadelphia," Decatur followed close after, and then the stream of men over the rail and through the open ports was constant. Complete as was the surprise, the entire absence of any resistance was astonishing. Few of the Turks had weapons in their hands, and those who had fled before the advancing Americans. On all sides the splashing of water told that the affrighted Turks were trying to make their escape that way. In ten minutes Decatur and his men had complete possession of the ship.

Doubtless at that moment the successful adventurcrs bitterly regretted that they could not take out of the harbor the noble frigate they had so nobly recaptured. But the orders of the commodore, and the dangers of their own situation, left them no choice. Nothing was to be done but to set fire to the frigate, and retreat witli ail possible expedition. The combustibles were brought from the ketch, and piled about the frigate, and lighted. So quickly was the work done, and so rapidly did the flames spread, that the people who lit the fires in the storerooms and cockpit had scarce time to get on deck before their retreat was cut off by the flames.

Before the ketch could be cast off from the sides of the frigate, the flames came pouring out of the port-holes, and flaming sparks fell aboard the smaller vessel, so that the ammunition which lay piled amid ships was in grave danger of being exploded. Axes and cutlasses were swung with a will ; and soon the bonds which held the two vessels together were cut, and the ketch was pushed off. Then the blue-jackets bent to their sweeps, and soon the " Intrepid " was under good headway.

"Now, lads," cried Decatur, "give them three cheers."

And the jackies responded with ringing cheers, that mingled with the roar of the flames that now had the frame of the " Philadelphia " in their control. Then they grasped their sweeps again, and the little vessel glided away through a hail of grape and round shot from the Tripolitan batteries and men-of-war, Though the whistle of the missiles was incessant, and the splash of round-shot striking the water could be heard on every side, no one in the boat was hurt ; and the only shot that touched the ketch went harmlessly through her mainsail. As they pulled away, they saw the flames catch the rigging of the "Philadelphia," and run high up the masts. Then the hatchways were burst open, and great gusts of flame leaped out. The shotted guns of the frigate were discharged in quick succession ; one battery sending its iron messengers into the streets of Tripoli, while the guns on the other side bore upon Fort English. The angry glare of the flames, and the flash of the cannon, lighted up the bay; while the thunders of the cannonade, and the cries of the Tripolitans, told of the storm that was raging.

The ruddy light of the burning ship bore good news to two anxious parties of Decatur's friends. Capt. Bainbridge and the other American officers whom the Tripolitans hid captured with the "Philadelphia" were imprisoned in a tower looking out upon the bay. The rapid thunder of the cannonade on this eventful night awakened them; and they rushed to their windows, to see the "Philadelphia," the Bashaw's boasted prize, in flames. Right lustily they added their cheers to the general tumult, nor ceased their demonstrations of joy until a surly guard came and ordered them from the windows.

Far out to sea another band of watchers hailed the light of the conflagration with joy. The "Siren" had gone into the offing when the "Intrepid" entered the harbor, and there awaited with intense anxiety the outcome of the adventure. After an hour's suspense, a rocket was seen to mount into the sky, and burst over Tripoli. It was the signal of success agreed upon. Boats were quickly lowered, and sent to the harbor's mouth to meet and cover the retreat of the returning party. Hardly had they left the side of the ship, when the red light in the sky told that the " Philadelphia " was burning ; and an hour later Decatur himself sprang over the taffrail, and proudly announced his victory.

Not a man had been lost in the whole affair. As the expedition had been perfect in conception, so it was perfect in execution. The adventure became the talk of all Europe. Lord Nelson, England's greatest admiral, said of it, "It was the most bold and daring act of the ages." And when the news reached the United States, Decatur, despite his youth, was made a captain.

Chapter XVII: Barbary Pirates (part 2)

Back to Bluejackets of 1776 Table of Contents

Back to American Revolution Book List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com