After this adventure, the three vessels continued their cruise along the eastern coast of Scotland. Continued good fortune, in the way of prizes, rather soothed the somewhat chafed feelings of Capt. Jones, and he soon recovered from the severe disappointment caused by the failure of his attack upon Leith. He found good reason to believe that the report of his exploits had spread far and wide in England, and that British sea-captains were using every precaution to avoid encountering him. British vessels manifested an extreme disinclination to come within hailing distance of any of the cruisers, although all three were so disguised that it seemed impossible to make out their warlike character. One fleet of merchantmen that caught sight of the "Bon Homme Richard" and the "Pallas" ran into the River Humber, to the mouth of which they were pursued by the two men-of-war.

Lying at anchor outside the bar, Jones made signal for a pilot, keeping the British flag flying at his peak. Two pilot-boats came out; and Jones, assuming the character of a British naval officer, learned from them, that besides the merchantmen lying at anchor in the river, a British frigate lay there waiting to convoy a fleet of merchantmen to the north.

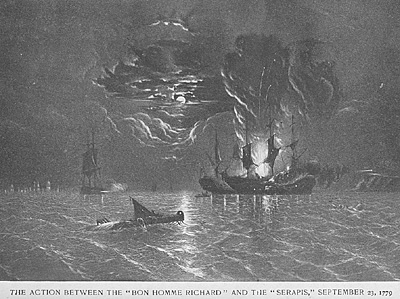

Jones tried to lure the frigate out with a signal that the pilots revealed to him; but, though she weighed anchor, she was driven back by strong headwinds that were blowing. Disappointed in this plan, Jones continued his cruise. Soon after he fell in with the "Alliance" and the "Vengeance;" aid, while off Flamborough Head, the little squadron encountered a fleet forty-one merchant ships, that, at the sight of the dreaded Yankee cruisers, crowded together like a flock of frightened pigeons, and made sail for the shore; while two stately men-of-war the "Serapis, forty-four," and the "Countess of Scarborough," twenty-two, moved forward give battle to the Americans.

Bon Homme Richard vs. Serapis

Bon Homme Richard vs. Serapis

Jones now stood upon the threshold of his greatest victory. His bold and chivalric mind had longed for battle, and recoiled from the less glorious pursuit of burning helpless merchantmen, and terrorizing small towns and villages. He now saw before him a chance to meet the enemy in a fair fight, muzzle to muzzle, and with no overpowering odds on either side.

Although the Americans had six vessels to the English two, the odds were in no wise in their favor. Two of the vessels were pilot-boats, which, of course, kept out of the battle. The "Vengeance," though ordered to render the larger vessels any possible assistance, kept out of the fight altogether, and even neglected to make any attempt to overhaul the flying band of merchantmen.

As for the "Alliance," under the erratic Landais, she only entered the conflict at the last moment; and then her broadsides, instead of being delivered into the enemy, crashed through the already shattered sides of the "Bon Flomme Richard." Thus the actual combatants were the "Richard " with forty guns, against the "Serapis" with forty-four; and the "Pallas" with twenty-two guns, against the "Countess of Scarborough" with twenty-two.

It was about seven o'clock in the evening of a clear September day the twenty-third that the hostile vessels bore down upon each other, making rapid preparations for the impending battle. The sea was fast turning gray, as the deepening twilight robbed the sky of its azure hue. A brisk breeze was blowing, that filled out the bellying sails of the ships, and beat the waters into little waves capped with snowy foam.

In the west the rosy tints of the autumnal sunset were still warm in the sky. Nature was in one of her most smiling moods, as these men with set faces, and hearts throbbing with the mingled emotions of fear and excitement, stood silent at their guns, or worked busily at the ropes of the great war-ships.

As soon as he became convinced of the character of the two English ships, Jones beat his crew to quarters, and signalled his consorts to form in line of battle. The people on the "Richard" went cheerfully to their guns; and though the ship was extremely short-handed, and crowded with prisoners, no voice was raised against giving immediate battle to the enemy. The actions of the other vessels of, the American fleet, however, gave little promise of any aid from that quarter. When the enemy was first sighted, the swift-sailing "Alliance " dashed forward to reconnoitre.

As she passed the "Pallas, " Landais cried out, that, if the stranger proved to be a forty-four, the only course for the Americans was immediate flight. Evidently the result of his investigations convinced him that in flight lay his only hope of safety ; for he quickly hauled off, and stood away from the enemy. The " Vengeance," too, ran off to windward, leaving the "Richard " and the "Pallas" to bear the brunt of battle.

It was by this time quite dark, and the position of the ships was outlined by the rows of open portholes gleaming with the lurid light of the battle-lanterns. On each ship rested a stillness like that of death itself. The men stood at their guns silent and thoughtful. Sweet memories of home and loved ones mingled with fearful anticipations of death or of mangling wounds in the minds of each. The little lads whose duty in time of action it was to carry cartridges from the magazine to the gunners had ceased their boyish chatter, and stood nervously at their stations. Officers walked up and down the decks, speaking words of encouragement to the men, glancing sharply at primers and breechings to see that all was ready, and ever and anon stooping to peer through the porthole at the line of slowly moving lights that told of the approach of the enemy.

On the quarter-deck, Paul Jones, with his officers about him, stood carefully watching the movements of the enemy through a night glass, giving occasionally a quiet order to the man at the wheel, and now and then sending an agile midshipman below with orders to the armorer, or aloft with orders for the sharp-shooters posted in the tops.

As the night came on, the wind died away to a gentle breeze, that hardly ruffled the surface of the water, and urged the ships toward each other but sluggishly. As they came within pistol-shot of each other, bow to bow, and going on opposite tacks, a hoarse cry came from. the deck of the "Serapis,"

"What ship is that?"

"What is that you say?"

"What ship is that? Answer immediately, or I shall fire into you."

Instantly with a flash and roar both vessels opened fire. The thunder of the broadsides reverberated over the waters ; and the bright flash of the cannon, together with the pale light of the moon just rising, showed Flamborough Head crowded with multitudes who had come out to witness the grand yet awful spectacle of a naval duel.

The very first broadside seemed enough to wreck the fortunes of the "Richard." In her gun-room were mounted six long eighteens, the only guns she carried that were of sufficient weight to be matched against the heavy ordnance of the "Serapis." At the very first discharge. two of these guns burst with frightful violence. Huge masses of iron wcre hurled in every direction, cutting through beams and stanchions, crashing through floors and bulkheads, and tearing through the agonized bodies of the men who served the guns. Hardly a man who was stationed in the gun-room escaped unhurt in the storm of iron and splinters. Several huge blocks of iron crashed through the upper deck, injuring the people on the deck above, and causing the cry to be raised, that, the magazine had blown up. This unhappy calamity not only rendered useless the whole battery of eighteen-pounders, thus forcing Jones to fight an eighteen-pounder frigate with a twelve-pounder battery, but it spread a panic among the men, who saw the dangers of explosion added to the peril they were in by reason of the enemy's continued fire.

Jones himself left the quarter-deck, and rushed forward among the men, cheering them on, and arousing them to renewed activity by his exertions. Now he would lend a hand at training some gun, now pull at a rope, or help a lagging powder-monkey on his way. His pluck and enthusiasm infused new life into the men; and they threw the heavy guns about like playthings, and cheered loudly as each shot told.

The two ships were at no time separated by a greater distance than half a pistol-shot, and were continually maneuvering to cross each others' bows, and get in a raking broadside. In this attempt, they crossed from one to the other side of each other; so that now the port and now the starboard battery would be engaged. From the shore these evolutions were concealed under a dense cloud of smoke, and the spectators could only see the tops of the two vessels moving slowly about before the light breeze; while the lurid flashes of the cannon, and constant thunder of the broadsides, told of the deadly work going on. At a little distance were the "Countess of Scarborough" and the "Pallas," linked in deadly combat, and adding the roar of their cannon to the general turmoil. It seemed to the watchers on the heights that war was coming very close to England.

The " Serapis " first succeeded in getting a raking position; and, as she slowly crossed her antagonist's bow, her guns were fired, loaded again, and again discharged, - the heavy bolts crashing into the "Richard's " bow, and ranging aft, tearing the flesh of the brave fellows on the decks, and cutting through timbers and cordage in their frightful course. At this moment, the Americans almost despaired of the termination of the conflict. The "Richard" proved to be old and rotten, and the enemy's shot seemed to tear her timbers to pieces ; while the " Serapis " was new, with timbers that withstood the shock of the balls like steel armor. Jones saw that in a battle with great guns he was sure to be the - loser. He therefore resolved to board.

Soon the " Richard " made an attempt to cross the bows of the Serapis, but not having way enough failed ; and the "Serapis" ran foul of her, with her long bowsprit projecting over the stern of the American ship. Springing from the quarter-deck, Jones with his own hands swung grappling-irons into the rigging of the enemy, and made tbr ships fast. As he bent to his work, he was a prominent target for every sharp-shooter on the British vessel, and the bullets hummed thickly about his cars ; but he never flinched. His work done, he clambered back to the quarter-deck, and set about gathering the boarders. The two vessels swung alongside each other. The cannonading was redoubled, and the heavy ordnance of the "Serapis" told fearfully upon the "Richard."

The American gunners were driven from their guns by the flying cloud of shot and splinters. Each party thought the other was about to board. The darkness and the smoke made all vision impossible; and the boarders on each vessel were crouched behind the bulwarks, ready to give a hot reception to their enemies. This suspense caused a temporary lull in the firing, and Capt. Pearson of the Serapis shouted out through the sulphurous blackness, "Have you struck your colors?"

"I have not yet begun to fight," replied Jones; and again the thunder of the cannon awakened the echoes on the distant shore.

As the firing recommenced, the two ships broke away and drifted apart. Again the Serapis sought to get a raking position; but by this time Jones had determined that his only hope lay in boarding. Terrible had been the execution on his ship. The cockpit was filled with the wounded. The mangled remains of the deck lay thick about the decks. The timbers of the ship were greatly shattered, and her cordage was so badly cut that skilful maneuvering was impossible. Many shot-holes were beneath the water-line, and the hold was rapidly filling. Therefore, Jones determined to run down his enemy, and get out his boarders, at any cost.

Soon the two vessels were foul again. Capt. Pearson, knowing that his advantage lay in long-distance fighting, strove to break away. Jones bent all his energies to the task of keeping the ships together. Meantime the battle raged fiercely. Jones himself, in his official report of the battle, thus describes the course of the fight:

- I directed the fire of one of the three cannon against the main-mast with double - headed shot, while the other two were exceedingly well served

with grape and canister shot, to silence the enemy's musketry, and clear her decks, which was at last effected. The enemy were, as I have since understood, on the instant for calling for quarter, when the cowardice or treachery of three of my under officers induced them to call to the enemy. The English commodore asked me if I demanded quarter; and I having answered him in the negative, they renewed the battle with double fury. They were unable to stand the deck; but the fury of their cannon, especially the lower battery, which was entirely formed of eighteen-pounders, was incessant.

On Fire

Both ships were set on fire in various places, and the scene was dreadful beyond the reach of language. To account for the timidity of my three under officers (I mean the gunner, the carpenter, and the master-at-arms), I must observe that the two first were slightly wounded; and as the ship had received various shots under water, and one of the pumps being shot away, the carpenter expressed his fear that she would sink, and the other two concluded that she was sinking, which occasioned the gunner to run aft on the poop, without my knowledge, to strike the colors. Fortunately for me a cannon-ball had done that before by carrying away the ensign staff: he was, therefore, reduced to the necessity of sinking as he supposedor of calling for quarter; and he preferred the latter."

Indeed, the petty officers were little to be blamed for considering the condition of the "Richard" hopeless. The great guns of the "Serapis," with their muzzles not twenty feet away, were hurling solid shot and grape through the flimsy shell of the American ship. So close together did the two ships come at times, that the rammers were sometimes thrust into the portholes of the opposite ship in loading. When the ships firs', swung together, the lower ports of the " Serapis " were closed to prevent the Americans boarding through them. But in the beat of the conflict the ports were quickly blown off, and the iron throats of the great guns again protruded, and dealt out their messages of death. How frightful was the scene!

In the two great ships were more than seven hundred men, their eyes lighted with the fire of hatred, their faces blackened with powder or made ghastly by streaks of blood. Cries of pain, yells of rage, prayers, and curses rose shrill above the thunderous monotone of the cannonade. Both ships were on fire; and the black smoke of the conflagration, mingled with the gray gunpowder smoke, and lighted up by the red flashes of the cannonade, added to the terrible picturesqueness of the scene.

The "Richard" seemed like a spectre ship, so shattered was her frame- work. From the main-mast to the stern post, her timbers above the water-line were shot away, a few blackened posts alone preventing the upper deck from falling. Through this ruined shell swept the shot of the "Serapis," finding little to impede their flight save human flesh and bone. Great streams of water were pouring into the hold. The pitiful cries of nearly two hundred prisoners aroused the compassion of an officer, who ran below and liberated them. Driven from the hold by the in-pouring water, these unhappy men ran to the deck, only to be swept down by the storm of cannon-shot and bullets. Fire, too, encompassed them; and the flames were so fast sweeping down upon the magazine, that Capt. Jones ordered the powder-kegs to be brought up and thrown into the sea. At this work, and at the pumps, the prisoners were kept employed until the end of the action.

But though the heavy guns of the "Serapis" had it all their own way below, shattering the hull of the "Richard," and driving the Yankee gunners from their quarters, the conflict, viewed from the tops, was not so one-sided. The Americans crowded on the forecastle and in the tops, where they continued the battle with musketry and handgrenades, with such murderous effect that the British were driven entirely from the upper deck. Once a party of about one hundred picked men, mustered below by Capt. Pearson, rushed to the upper deck of the "Serapis," and thence made a descent upon the deck of the "Richard," firing pistols, brandishing cutlasses, and yelling like demons. But the Yankee tars were ready for them at that game, and gave the boarders so spirited a reception with pikes and cutlasses, that they were ready enough to swarm over the bulwarks, and seek again the comparative safety of their own ship.

But all this time, though the Americans were making a brave and desperate defence, the tide of battle was surely going against them. Though they held the deck of the "Richard" secure against all comers. yet the Englishmen were cutting the ship away from beneath them, with continued heavy broadsides. Suddenly the course of battle was changed, and victory took her stand with the Americans, all through. the daring and coolness of one man, no officer, but an humble jacky.

The rapid and accurate fire of the sharp-shooters on the "Richard" had driven all the riflemen of the "Serapis" from their posts in the tops. Seeing this, the Americans swarmed into the rigging of their own ship, and from that elevated station poured down a destructive fire of hand-grenades upon the decks of the enemy, The sailors on the deck of the "Richard" seconded this attack, by throwing the same missiles through the open ports of the enemy.

At last one American topman filled a bucket with grenades, and hanging it on his left arm, clambered out on the yard-arm of the "Richard," that stretched far out over the deck of the British ship. Cautiously the brave fellow crept out on the slender spar. His comrades below watched his progress, while the sharp-shooters kept a wary eye on the enemy, lest some watchful rifleman should pick off the adventurous blue-jacket. Little by little the nimble sailor crept out on the yard, until he was over the crowded gun-deck of the "Serapis." Then, lying at full length on the spar, and somewhat protected by it, he began to shower his missiles upon the enemy's gun-deck. Great was the execution done by each grenade; but at last, one better aimed than the rest fell through the main hatch to the main deck. There was a flash, then a succession of quick explosions; a great sheet of flame gushed up through the hatchway, and a chorus of cries told of some frightful tragedy enacted below.

It seemed that the powder-boys of the "Serapis" had been too active in bringing powder to the guns, and, instead of bringing cartridges as needed, had kept one charge in advance of the demand; so that behind every gun stood a cartridge, making a line of cartridges on the deck from bow to stern. Several cartridges had been broken, so that much loose powder lay upon the deck. This was fired by the discharge of the hand-grenade, and communicated the fire to the cartridges, which exploded in rapid succession, horribly burning scores of men. More than twenty men were killed instantly; and so great was the flame and the force of the explosion, that many of them were left with nothing on but the collars and wristbands of their shirts, and the waistbands of their trousers. It is impossible to conceive of the horror of the sight.

Hand Grenade

Capt. Pearson in his official report of the battle, speaking of this occurrence, says,

- "A hand-grenade being thrown in at one of the lower ports, a cartridge of powder was set on fire, the flames of which, running from cartridge to cartridge all the way aft, blew up the whole of the people and officers that were quartered abaft the main-mast; from which unfortunate circumstance those guns were rendered useless for the remainder of the action, and I fear that the greater part of the people will lose their lives."

This event changed the current of the battle. The English were hemmed between decks by the fire of the American topmen, and they found that not even then were they protected from the fiery hail of hand-grenades. The continual pounding of double-headed shot from a gun which Jones had trained upon the main-mast of the enemy had finally cut away that spar; and it fell with a crash upon the deck, bringing down spars and rigging with it. Flames were rising from the tarred cordage, and spreading to the framework of the ship. The Americans saw victory within their grasp.

But at this moment a new and most unsuspected enemy appeared upon the scene. The "Alliance," which had stood aloof during the heat of the conflict, now appeared, and, after firing a few shots into the "Serapis," ranged slowly down along the "Richard," pouring a murderous fire of grape-shot into the already shattered ship. Jones thus tells the story of this treacherous and wanton assault:

- "I now thought that the battle was at an end. But, to my utter astonishment, he discharged a broadside full into the stern of the 'Bon Homme Richard.' We called to him for God's sake to forbear. Yet he passed along the off-side of the ship, and continued firing. There was no possibility of his mistaking the enemy's ship for the 'Bon Homme Richard,' there being the most essential difference in their appearance and construction. Besides, it was then full moonlight ; and the sides of the 'Bon Homme Richard' were all black, and the sides of the enemy's ship were yellow. Yet, for the greater security, I showed

the signal for our reconnaissance, by putting out three lanterns--one at the bow, one at the stern, and one at the middle, in a horizontal line.

Every one cried that he was firing into the wrong ship, but nothing availed. He passed around, firing into the 'Bon Homme Richard,' head, stern, and broadside, and by one of his volleys killed several of my best men, and mortally wounded a good officer of the forecastle. My situation was truly deplorable. The 'Bon Homme Richard' received several shots under the water from the Alliance. The leak gained on the pumps, and the fire increased much on board both ships. Some officers entreated me to strike of whose courage and sense I entertain a high opinion. I would not, however, give up the point."

Fortunately Landais did not persist in his cowardly attack upon his friends in the almost sinking ship, but sailed off, and allowed the Richard to continue her life-and-death struggle with her enemy. The struggle was not now of long duration; for Capt. Pearson, seeing that his ship was a perfect wreck, and that the fire was gaining head way, hauled down his colors with his own hands, since none of his, men could be persuaded to brave the fire from the tops of the "Richard."

As the proud emblem of Great Britain fluttered down, Lieut. Richard Dale turned to Capt. Jones, and asked permission to board the prize. Receiving an affirmative answer, he jumped on the gunwale, seized the mainbrace-pendant, and swung himself upon the quarter-deck of the captured ship.

Midshipman Mayrant, with a large party of sailors, followed. So great was the confusion on the " Serapis," that few of the Englishmen knew that the ship had been surrendered. As Mayrant came aboard, he was mistaken for the leader of a boarding-party, and run through the thigh with a pike.

Capt. Pearson was found standing alone upon the quarter-deck, contemplating with a sad face the shattered condition of his once noble ship, and the dead bodies of his brave fellows lying about the decks. Stepping up to him, Lieut. Dale said,

"Sir, I have orders to send you on board the ship alongside."

At this moment, the first lieutenant of the "Serapis " came up hastily, and inquired, "Has the enemy struck her flag?

"No, sir," answered Dale. "On the contrary, you have struck to us."

Turning quickly to his commander, the English lieutenant asked,

"Have you struck, sir?"

"Yes, I have," was the brief reply.

"I have nothing more to say," remarked the officer, and turning about was in the act of going below, when Lieut. Dale stopped him, saying, "It is my duty to request you, sir, to accompany Capt. Pearson on board the ship alongside."

"If you will first permit me to go below," responded the other, "I will silence the firing of the lower deck guns."

"This cannot be permitted," was the response; and, silently bowing his head, the lieutenant followed his chief to the victorious ship, while two midshipmen went below to stop the firing.

Lieut. Dale remained in command of the "Serapis." Seating himself on the binnacle, he ordered the lashings which had bound the two ships throughout the bloody conflict to be cut. Then the head-sails were braced back, and the wheel put down. But, as the ship. had been anchored at the beginning of the battle, she refused to answer either helm or canvas. Vastly astounded at this, Dale leaped from the binnacle; but his legs refused to support him, and he fell heavily to the deck. His followers sprang to his aid ; and it was found that the lieutenant had been severely wounded in the leg by a splinter, but had fought out the battle without ever noticing his hurt.

Wreck and Carnage

So ended this memorable battle. But the feelings of pride and exultation so natural to a victor died away in the breast of the American captain as he looked about the scene of wreck and carnage. On all sides lay the mutilated bodies of the gallant fellows who had so bravely stood to their guns amid the storm of death-dealing missiles. There they lay, piled one on top of the other, some with their agonized writhings caught and fixed by death; others calm and peaceful, as though sleeping. Powder-boys, young and tender, lay by the side of grizzled old seamen. Words cannot picture the scene. In his journal Capt. Jones wrote:

- "A person must have been an eye-witness to form a just idea of the

tremendous scene of carnage, wreck, and ruin that everywhere appeared.

Humanity cannot but recoil from the prospect of such finished horror, and

lament that war should produce such fatal consequences."

But worse than the appearance of the main deck was the scene in the cockpit and along the gun-deck, which had been converted into a temporary hospital. Here lay the wounded, ranged in rows along the deck. Moans and shrieks of agony were heard on every side. The surgeons were busy with their glittering instruments. The tramp of men on the decks overhead, and the creaking of the timbers of the water-logged ship, added to the cries of the wounded, made a perfect bedlam of the place.

It did not take long to discover that the "Bon Homme Richard" was a complete wreck, and in a sinking condition. The gallant old craft had kept afloat while the battle was being fought ; but now, that the victory had remained with her, she had given up the struggle against the steadily encroaching waves. The carpenters who had explored the hold came on deck with long faces, and reported that nothing could be done to stop the great holes made by the shot of the "Serapis."

Therefore Jones determined to remove his crew and all the wounded to the 11 Serapis," and abandon the noble " Richard " to her fate. Accordingly, all available hands were put at the pumps, and the work of transferring the wounded was begun. Slings were rigged over the side; and the poor shattered bodies were gently lowered into the boats awaiting them, and, on reaching the "Serapis," were placed in cots ranged along the main deck. All night the work went on; and by ten o'clock the next morning there were left on the "Richard" only a few sailors, who alternately worked at the pumps, and fought the greedily encroaching flames.

For Jones did not intend to desert the good old ship without a struggle to save her, even though both fire and water were warring against her. Not until the morning dawned did the Americans fully appreciate how shattered was the hulk that stood between them and a watery grave. Fenimore Cooper, the pioneer historian of the United States navy, writes :

"When the day dawned, an examination was made into the situation of the 'Richard.' Abaft on a line with those guns of the 'Serapis' that had not been disabled by the explosion, the timbers were found to be nearly all beaten in, or beaten out, -- for in this respect there was little difference between the two sides of the ship -- and it was said that her poop and upper decks would have fallen into the gun-room, but for a few buttocks that had been missed.

Indeed, so large was the vacuum, that most of the shot fired from this part of the 'Serapis,' at the close of the action, must have gone through the 'Richard' without touching any thing. The rudder was cut from the stern post, and the transoms were nearly driven out of her. All the after-part of the ship, in particular, that was below the quarter-deck was torn to pieces ; and nothing had saved those stationed on the quarter-deck but the impossibility of sufficiently elevating guns that almost touched their object."

Despite the terribly shattered condition of the ship, her crew worked manfully to save her. But, after fighting the flames and working the pumps all day, they were reluctantly forced to abandon the good ship to her fate. It was nine, o'clock at night, that the hopelessness of the task became evident. The "Richard" rolled heavily from side to side. The sea was up to her lower portholes. At each roll the water gushed through her port-holes, and swashed through the hatchways.

At ten o'clock, with a last dying surge, the shattered hulk plunged to her final resting-place, carrying with her the bodies of her dead. They had died the noblest of all deaths, the death of a patriot killed in doing battle for his country. They receive the grandest of all burials, the burial of a sailor who follows his ship to her grave, on the hard, white sand, in the calm depths of the ocean.

How many were there that went down with the ship? History does not accurately state. Capt. Jones himself was never able to tell how great was the number of dead upon his ship. The most careful estimate puts the number at forty-two. Of the wounded on the American ship, there were about forty. All these were happily removed from the Richard before she sunk.

On the "Serapis" the loss was much greater; but here, too, history is at fault, in that no official returns of the killed and wounded have been preserved. Capt. Jones's estimate, which is probably nearly correct, put the loss of the English ship at about a hundred killed, and an equal number wounded.

The sinking of the Richard left the Serapis crowded with wounded of both nations, prisoners, and the remnant of the crew of the sunken ship. No time was lost in getting the ship in navigable shape, and in clearing away the traces of the battle. The bodies of the dead were thrown overboard. The decks were scrubbed and sprinkled with hot vinegar. The sound of the hammer and the saw was heard on every hand, as the carpenters stopped the leaks, patched the deck, and rigged new spars in place of those shattered by the "Richard's" fire. All three of the masts had gone by the board. Jury masts were rigged ; and with small sails stretched on these the ship beat about the ocean, the plaything of the winds. Her consorts had left her. Landais, seeing nc chance to rob Jones of the horror of the victory, had taken the "Alliance" to other waters. The " Pallas " had been victorious in her contest with the "Countess of Scarborough;" and as soon as the issue of the conflict between the "Bon Homme Richard " and the "Serapis " had become evident, she made off with her prize, intent upon gaining a friendly port. The "Richard," after ten days of drifting, finally ran into Texel, in the north of Holland.

Praise

The next year was one of comparative inactivity for Jones. He enjoyed for a time the praise of all friends of the revolting colonies. He was the lion of Paris. Then came the investigation into the action of Landais at the time of the great battle. Though his course at that time was one of open treachery, inspired by his wish to have Jones strike to the "Serapis," that he might have the honor of capturing both ships, Landais escaped any punishment at the hands of his French compatriots. But he was relieved of the command of the "Alliance," which was given to Jones. Highly incensed at this action, the erratic Frenchman incited the crew of the "Alliance" to open mutiny, and, taking command of the ship himself, left France and sailed for America, leaving Commodore Jones in the lurch.

On his arrival at Philadelphia, Landais strove to justify his action by blackening the character of Jones, but failed in this, and was dismissed the service. His actions should be regarded with some charity, for the man was doubtless of unsound mind. His insanity became even more evident after his dismissal from the navy; and from that time, until the time of his death, his eccentricities made him generally regarded as one mentally unsound.

Jones, having lost the "Alliance" by the mutiny of Landais, remained abroad, waiting for another ship. He travelled widely on the Continent, and was lavishly entertained by the rich and noble of every nation. Not until October, 1780, did he again tread the deck of a vessel under his own command.

The Ariel

The ship which the French Government finally fitted out and put in command of Paul Jones was the "Ariel," a small twenty-gun ship. This vessel the adventurous sailor packed full of powder and cannon-balls, taking only provisions enough for nine weeks, and evidently expecting to live off the prizes he calculated upon taking. He sailed from l'Orient on a bright October afternoon, under clear skies, and with a fairwind, intending to proceed directly to the coast of America. But the first night out there arose a furious gale. The wind howled through the rigging, tore the sails from the ring-bolts, snapped the spars, and seriously wrecked the cordage of the vessel. The great waves, lashed into fury by the hurricane, smote against the sides of the little craft as though they would burst through her sheathing. The ship rolled heavily; and the yards, in their grand sweep from side to side, often plunged deep into the foaming waves.

At last so great became the strain upon the vessel, that the crew were set to work with axes to cut away the foremast. Balancing themselves upon the tossing, slippery deck, holding fast to a rope with one hand, while with the other they swung the axe, the gallant fellows finally cut so deep into the heart of the stout spar, that a heavy roll of the ship made it snap off short, and it fell alongside, where it hung by the cordage. The wreck was soon cleared away; and as this seemed to ease the ship somewhat, and as she was drifting about near the dreaded rock of Penmarque, the anchors were got out. But in the mean time the violent rolling of the "Ariel" had thrown the heel of the main-mast from the step; and the heavy mast was reeling about, threatening either to plough its way upward through the gun-deck, or to crash through the bottom of the ship.

It was determined to cut away this mast; but, before this could be done, it fell, carrying with it the mizzen-mast, and crushing in the deck on which it fell. Thus dismasted, the " Ariel " rode out the gale. All night and all the next day she was tossed about on the angry waters. Her crew thought that their last hour had surely come. Over the shrieking of the gale, and the roaring of the waves, rose that steady, all-pervading sound, which brings horror to the mind of the sailor -- the dull, monotonous thunder of the breakers on the reef of Penmarque. But the " Ariel " was not fated to be ground to pieces on the jagged teeth of the cruel reef. Though she drifted about, the plaything of the winds and the waves, she escaped the jaws of Penmarque. Finally the gale subsided; and, with hastily devised jury-masts, the shattered ship was taken back to l'Orient to refit.

Two months were consumed in the work of getting the shattered vessel ready for sea. When she again set out, she met with no mishap, until, when near the American coast, she fell in with a British vessel to which she gave battle. A sharp action of a quarter of an hour forced the Englishman to strike his colors ; but, while the Americans were preparing to board the prize, she sailed away, vastly to the chagrin and indignation of her would-be captors.

The short cruise of the " Ariel " was the last service rendered by Paul Jones to the American Colonies. On his arrival at Philadelphia, he was dined and feted to his heart's desire; he received a vote of thanks from Congress ; he became the idol of the populace. But the necessities of the struggling colonies were such that they were unable to build for him a proper war-ship, and he remained inactive upon shore until the close of the Revolution, when he went abroad, and took service with Russia.

He is the one great character in the naval history of the Revolution. He is the first heroic figure in American naval annals. Not until years after his death did men begin to know him at his true worth. He was too often looked upon as a man of no patriotism, but wholly mercenary; courageous, but only with the daring of a pirate. Not until he had died a lonely death, estranged from the country he had so nobly served, did men come to know Paul Jones as a model naval officer, high-minded in his patriotism. pure in his life, elevated in his sentiments, and as courageous as a lion.

Chapter X: Exploits of Biddle and Tucker

Back to Bluejackets of 1776 Table of Contents

Back to American Revolution Book List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com