I have already spoken of the farcical affair between the fleet under Ezekiel Hopkins and the English frigate "Glasgow," in which the English vessel, by superior seamanship, and taking advantage of the blunders of the Americans, escaped capture. The primary result of this battle was to cause the dismissal from the service of Hopkins. But his dismissal led to the advancement of a young naval officer, whose name became one of the most glorious in American naval annals, and whose fame as a skilful seaman has not been tarnished by the hand of time.

I have already spoken of the farcical affair between the fleet under Ezekiel Hopkins and the English frigate "Glasgow," in which the English vessel, by superior seamanship, and taking advantage of the blunders of the Americans, escaped capture. The primary result of this battle was to cause the dismissal from the service of Hopkins. But his dismissal led to the advancement of a young naval officer, whose name became one of the most glorious in American naval annals, and whose fame as a skilful seaman has not been tarnished by the hand of time.

At the time of the escape of the "Glasgow," there was serving upon the "Alfred" a young lieutenant, by name John Paul Jones. Jones was a Scotchman. His rightful name was John Paul; but for some reason, never fully understood, he had assumed the surname of Jones, and his record under the name of Paul Jones forms one of the most glorious chapters of American naval history. When given a lieutenant's commission in the colonial navy, Jones was twenty-nine years old. From the day when a lad of thirteen years he shipped for his first voyage, he had spent his life on the ocean. He had served on peaceful merchantmen, and ill the less peaceful, but at that time equally respectable, slave-trade. A small inheritance had enabled him to assume the station of a Virginia gentleman ; and he had become warmly attached to American ideas and principles, and at the outbreak of the Revolution put his services at the command of Congress.

He was first offered a captain's commission with the command of the "Providence," mounting twelve guns and carrying one hundred men. But with extraordinary modesty the young sailor declined, saying that he hardly felt himself fitted to discharge the duties of a first lieutenant. The lieutenant's commission, however, he accepted ; and it was in this station that with his own hands he hoisted the first American flag to the masthead of the "Alfred."

The wretched fiasco which attended the attack of the American fleet upon the "Glasgow" was greatly deplored by Jones. However, lie refrained from any criticism upon his superiors, and sincerely regreted the finding of the court of inquiry, by which the captain of the "Providence" was dismissed the service, and Lieut. Paul Jones recommended to fill the vacancy.

The duties which devolved upon Capt. Jones were manifold and arduous. The ocean was swarming with powerful British men-of-war, which in his little craft he must avoid, while keeping a sharp outlook for foemen with whom he was equally matched. More than once, from the masthead of the " Providence," the lookout could discover white sails of one or more vessels, any one of which, with a single broadside, could have sent the audacious Yankee to the bottom. But luckily the "Providence" was a fast sailer, and wonderfully obedient to her helm.

To her good sailing qualities, and to his own admirable seamanship, Jones owed more than one fortunate escape. Once, when almost overtaken by a powerful man-of-war, he edged away until he brought his pursuer on his weather quarter ; then, putting his helm up suddenly, he stood dead before the wind, thus doubling on his course, and running past his adversary within pistol-shot of her guns, but in a course directly opposite to that upon which she was standing. The heavy war-ship went plunging ahead like a heavy hound eluded by the agile fox, and the Yankee proceeded safely on her course.

Stranger

Some days later the "Providence" was lying to on the great banks near the Isle of Sables. it was a holiday for the crew; for no sails were sight, and Capt. Jones had indulgently allowed them to get out their cod-lines and enjoy an afternoon's fishing. In the midst of their sport, as they hauled in the finny monsters right merrily, the hail of the lookout warned them of a strange sail.

The stranger drew rapidly nearer, and was soon made out to be a war vessel. Jones, finding after a short trial that his light craft could easily outstrip the lumbering man-of-war, managed to keep just out of reach. Now and then the pursuer would luff up and let fly a broadside ; the shot skipping along over the waves, but sinking before they reached the "Providence." Jones, who had an element of humor in his character, responded to this cannonade with one musket, which, with great solemnity, was discharged in response to each broadside. After keeping up this burlesque battle for some hours, the "Providence" spread her sails, and soon left her foe hull down beneath the horizon.

After having thus eluded his pursuer, Jones skirted the coast of Cape Breton, and put into the harbor of Canso, where be found three British fishing schooners lying at anchor. The inhabitants of the little fishing village were electrified to see the " Providence " cast anchor in the harbor, and, lowering her boats, send two crews of armed sailors to seize the British craft. No resistance was made, however; and the Americans burned one schooner, scuttled a second, and after filling the third with fish, taken from the other two, took her out of the harbor with the Providence leading the way.

From the crew of the captured vessel, Jones learned that at the Island of Madame, not far from Canso, there was a considerable flotilla of British merchantmen. Accordingly he proceeded thither with the intention of destroying them. On arriving he found the harbor too shallow to admit the Providence and accordingly taking up a position from which he could, with his cannon, command the harbor, be despatched armed boats' crews to attack the shipping. On entering the harbor, the Americans found nine British vessels lying at anchor. Ships and brigs, as well as small fishing schooners, were in the fleet. It was a rich prize for the Americans, and it was won without bloodshed; for the peaceful fishermen offered no resistance to the Yankees, and looked upon the capture of their vessels with amazement. The condition of these poor men, thus left on a bleak coast with no means of escape, appealed strongly to Jones's humanity. He therefore told them, that, if they would assist him in making ready for sea such of the prizes as he wished to take with him, he would leave them vessels enough to carry them back to England. The fishermen heartily agreed to the proposition, and worked faithfully for several days at the task of fitting out the captured vessels.

The night before the day on which Jones had intended leaving the harbor, the wind came on to blow, and a violent storm of wind and rain set in. Even the usually calm surface of the little harbor was lashed to fury by the shrieking wind. The schooner Sea-Flower one of the captured prizes - was torn from her moorings ; and though her crew cut out the sweeps, and struggled valiantly for headway against the driving storm, she drifted on shore, and lay there a total wreck. The schooner " Ebenezer," which Jones had brought from Canso laden with fish, drifted on a sunken reef, and was there so battered by the roaring waves that she went to pieces. Her crew, after vainly striving to launch the boats, built a raft, and saved themselves on that.

The next day the storm abated; and Capt. Jones, taking with him three heavily laden prizes, left the harbor, and turned his ship's prow homeward. The voyage to Newport, then the headquarters of the little navy, was made without other incident than the futile chase of three British ships, which ran into the harbor of Louisbourg. On his arrival, Jones reported that he had been cruising for forty-seven days, and in that time had captured sixteen prizes, beside the fishing-vessels he burned at Cape Breton. Eight of his prizes he had manned, and sent into port; the remainder he had burned. It was the first effective blow the colonists had yet struck at their powerful foe upon the ocean.

Hardly had Paul Jones completed this first cruise, when his mind, ever active in the service of his country, suggested to him a new enterprise in which he might contribute to the cause of American liberty. At this early period of the Revolution, the British were treating American prisoners with almost inconceivable barbarity. Many were sent to the "Old Jersey" prison-ship, of whose horrors we shall read something later on. Others, to the number of about a hundred, were taken to Cape Breton, and forced to labor like Russian felons in the underground coal-mines. Jones's plan was bold in its conception, but needed only energy and promptitude to make it perfectly feasible.

He besought the authorities to give him command of a squadron, that he might move on Cape Breton, destroy the British coal and fishing vessels always congregated there, and liberate the hapless Americans who were passing their lives in the dark misery of underground mining. His plan was received with favor, but the authorities lacked the means to give him the proper aid. However, two vessels, the "Alfred" and the "Providence," were assigned to him; and he went speedily to work to prepare for the adventure.

At the outset, he was handicapped by lack of men. The privateers were then fitting out in every port; and seamen saw in privateering easier service, milder discipline, and greater profits than they could hope for in the regular navy. When, by hard work, the muster-roll of the "Alfred" showed her full complement of men shipped, the stormy month of November had arrived, and the golden hour for success was past.

Nevertheless, Jones, taking command of the "Alfred," and putting the "Providence" in the command of Capt. Hacker, left Newport, and laid his course to the northward. When he arrived off the entrance to the harbor of Louisbourg, he was so lucky as to encounter an English brig, the "Mellish," which, after a short resistance, struck her flag. She proved to be laden with heavy warm clothing for the British troops in Canada. This capture was a piece of great good fortune for the Americans, and many a poor fellow in Washington's army that winter had cause to bless Paul Jones for his activity and success.

The day succeeding the capture of the " Mellish " dawned gray and cheerless. Light flurries of snow swept across the waves, and by noon a heavy snowstorm, driven by a violent north-east gale, darkened the air, and lashed the waves into fury. Jones stood dauntless at his post on deck, encouraging the sailors by cheery words, and keeping the sturdy little vessel on her course.

All day and night the storm roared; and when, the next morning, Jones, wearied by his ceaseless vigilance, looked anxiously across the waters for his consort, she was not to be seen. The people on the "Alfred" supposed, of course, that the " Providence " was lost, with all on board, and mourned the sad fate of their comrades. But, in fact, Capt. Hacker, affrighted by the storm, had basely deserted his leader during the night, and made off for Newport, leaving Jones to prosecute his enterprise alone.

Jones recognized in this desertion the knell of the enterprise upon which he had embarked. Nevertheless, he disdained to return to port: so sending the " Mellish " and a second prize, which the British afterwards recaptured, back to Massachusetts, he continued his cruise along the Nova Scotia coast. Again he sought out the harbor of Canso, and, entering it, found a large English transport laden with provisions aground just inside the bar. Boats' crews from the "Alfred" soon set the torch to the stranded ship, and then, landing, fired a huge warehouse filled with whale-oil and the products of the fisheries.

Leaving the blazing pile behind, the "Alfred " put out again into the stormy sea, and made for the northward.

As he approached Louisbourg, Jones fell in with a considerable fleet of British coal-vessels, in convoy of the frigate "Flora." A heavy fog hung over the ocean ; and the fleet Yankee, flying here and there, was able to cut out and capture three of the vessels without alarming the frigate, that continued unsuspectingly on her course. Two days later, Jones snapped up a Liverpool privateer, that fired scarcely a single gun in resistance. Then crowded with prisoners, embarrassed by prizes, and short of food and water, the Alfred turned her course homeward.

Five valuable prizes sailed in her wake. Anxiety for the safety of these gave Jones no rest by day or night. He was ceaselessly on the watch lest some hostile man-of-war should overhaul his fleet, and force him to abandon his hard-won fruits of victory. All went well until, when off St. George's Bank, he encountered the frigate "Milford," the same craft to whose cannon-balls Jones, but a few months before, had tauntingly responded with musket-shots.

It was late in the afternoon when the "Milford " was sighted; and Jones, seeing that she could by no possibility overtake his squadron before night, ordered his prizes to continue their course without regard to any lights or apparent signals from the "Alfred." When darkness fell upon the sea, the Yankees were scudding along on the starboard tack with the Englishman coming bravely up astern. From the tops of the "Alfred " swung two burning lanterns, which the enemy doubtless pronounced a bit of beastly stupidity on the part of the Yankee, affording, as it did, an excellent guide for the pursuer to steer by. But during the night the wily Jones changed his course. The prizes, with the exception of the captured privateer, continued on the starboard tack.

The "Alfred" and the privateer made off on the port tack, with the "Milford" in full cry in their wake. Not until the morning dawned did the Englishman discover how he had been tricked.

Having thus secured the safety of his prizes, it only remained for Jones to escape with the privateer. Unluckily, however, the officer put in charge of the privateer proved incapable, and his craft fell into hands the British. Jones, however, safely carried the "Alfred" clear of the Milford's guns, and, a heavy storm coming up, soon eluded his foe in the snow and darkness. Thereupon he shaped his course for Boston, where he arrived on the 5th of December, 1776. Had he been delayed two days longer, both his provisions and his water would have been exhausted.

For the ensuing six months Jones remained on shore, not by any means inactive, for his brain teemed with great projects for his country's service. He had been deprived of the command of the "Alfred," and another ship was not easily to be found: so he turned his attention to questions of naval organization, and the results of many of his suggestions are observable in the United States navy to-day. It was not until June 14, 1777, that a command was found for him. This was the eighteen-gun ship "Ranger," built to carry a frigate's battery of twenty-six guns. She had been built for the revolutionary government, at Portsmouth, and was a solid craft, though miserably slow and somewhat crank.

Jones, though disappointed with the sailing qualities of the craft, was nevertheless vastly delighted to be again in command of a man-of-war, andd wasted no-time in getting her ready for sea.

It so happened, that, on the very day Paul Jones received his commission as commander of the "Ranger," the Continental Congress adopted the Stars and Stripes for the national flag. Jones, anticipating this action, had prepared a flag in accordance with the proposed designs, and, upon hearing of the action of Congress, had it run to the masthead, while the cannon of the "Ranger" thundered out their deep-mouthed greetings to lie starry banner destined to wave over the most glorious nation of the Earth. Thus it happened that the same hand that had given the pine-tree banner to the winds was the first to fling out to the breezes the bright folds of the Stars and Stripes.

Early in October the "Ranger" left Portsmouth, and made for the coast of France. Astute agents of the Americans in that country were having a fleet, powerful frigate built there for Jones, which be was to take, leaving the sluggish "Ranger " to be sold. But, on his arrival at Nantes, Jones was grievously disappointed to learn that the British Government had so vigorously protested against the building of a vessels-of-war in France for the Americans, that the French Government had been obliged to notify the American agents that their plan must be abandoned.

France was at this time at peace with Great Britain, and, though inclined to be friendly with the rebellious colonies, was not ready to entirely abandon her position as a neutral power. Later, when she took up arms against England, she gave the Americans every right in her ports they could desire.

Jones thus found himself in European waters with a vessel too weak to stand against the frigates England could send to take her, and too slow to elude them. But he determined to strike some effective blows for the cause of liberty. Accordingly he planned an enterprise, which, for audacity of conception and dash in execution, has never been equalled by any naval expedition since.

This was nothing less than a virtual invasion of England. The "Ranger" lay at Brest. Jones planned to dash across the English Channel, and cruise along the coast of England, burning shipping and towns, as a piece of retaliation upon the British for their wanton outrages along the American coast. It was a bold plan. The channel was thronged with the heavy frigates of Great Britain, any one of which could have annihilated the audacious Yankee cruiser. Nevertheless, Jones determined to brave the danger.

At the outset, it seemed as though his purpose was to be balked by heavy weather. For days after the "Ranger" left Brest, she battled against the chop-seas of the English Channel. The sky was dark, and the light of the sun obscured by gray clouds. The wind whistled through the rigging, and tore at the tightly furled sails. Great green walls of water, capped with snowy foam, beat thunderously against the sides of the 11 Ranger." Now and then a port would be driven in, and the men between decks drenched by the incoming deluge. The "Ranger" had encountered an equinoctial gale in its worst form.

When the gale died away, Jones found himself off the Scilly Islands, in full view of the coast of England. Here he encountered a merchantman, which he took and scuttled, sending the crew ashore to spread the news that an American man-of-war was ravaging the channel. Having alarmed all England, he changed his hunting-ground to St. George's Channel and the Irish Sea, where he captured several ships ; sending one, a prize, back to Brest. He was in waters with which he had been familiar from his youth, and he made good use of his knowledge ; dashing here and there, lying in wait in the highway of commerce, and then secreting himself in some sequestered cove while the enemy's ship-of-war went by in fruitless search for the marauder. All England was aroused by the exploits of the Yankee cruiser. Never since the days of the Invincible Armada had war been so brought home to the people of the tight little island. Long had the British boastfull claimed the title of monarch of the seas. Long had they sung the vainglorious song:

- "Britannia needs no bulwarks,

No towers along the steep;

Her march is o'er the mountain waves,

Her home is on the deep."

But Paul Jones showed Great Britain that her boasted power was a bubble. He ravaged the seas within cannon-shot of English headlands. He captured and burned merchantmen, drove the rates of insurance up to panic prices, paralyzed British shipping-trade, and even made small incursions into British territory.

The reports that reached Jones of British barbarity along the American coast, of the burning of Falmouth, of tribute levied on innumerable seaport towns, all aroused in him a determination to strike a retaliatory blow. Whitehaven, a small seaport, was the spot chosen by him for attack; and he brought his ship to off the mouth of the harbor late one night, intending to send in a boat's crew to fire the shipping. But so strong a wind sprung up, as to threaten to drive the ship ashore; and Jones was forced to make sail, and get an offing. A second attempt, made upon a small harbor called Lochryan, on the western coast of Scotland, was defeated by a like cause.

But the expedition against Lochryan, though in itself futile, was the means of giving Jones an opportunity to show his merits as a fighter. Soon after leaving Lochryan, he entered the bay of Carrichfergus, on which is situated the Irish commercial city of Belfast. The bay was constantly filled with merchantmen; and the "Ranger," with her ports closed, and her warlike character carefully disguised, excited no suspicion aboard a trim, heavy-built craft that lay at anchor a little farther up the bay. This craft was the British man-of-war "Drake," mounting twenty guns. Soon after his arrival in the bay, Jones learned the character of the "Drake," and determined to attempt her capture during the night. Accordingly he dropped anchor near by, and, while carefully concealing the character of his craft, made every preparation for a midnight fight. The men sat between decks, sharpening cutlasses, and cleaning and priming their pistols; the cannon were loaded with grape, and depressed for work at close quarters; battle lanterns were hung in place, ready to be lighted at the signal for action.

At ten o'clock, the tramp of men about the capstan gave notice that the anchor was being brought to the catheads. Soon the creaking of cordage, and the snapping of the sails, told that the fresh breeze was being caught by the spreading sails. Then the waves rippled about the bow of the ship, and the "Ranger" was fairly under way.

It was a pitch-dark night, but the lights on board the "Drake" showed where she was lying. On the "Ranger" all lights were extinguished, and no noise told of her progress towards her enemy. It was the captain's plan to run his vessel across the "Drake's" cable, drop his own anchor, let the "Ranger" swing alongside the Englishman, and then fight it out at close quarters.

But this plan, though well laid, failed of execution. The anchor was not let fall in season; and the "Ranger," instead of bringing up alongside her enemy, came to anchor half a cable-lengtb astern. The swift-flowing tide and the fresh breeze made it impossible to warp the ship alongside: so Jones ordered the cable cut, and the "Ranger" scudded down the bay before the ever-freshening gale. It does not appear that the people on the "Drake" were aware of the danger they so narrowly escaped.

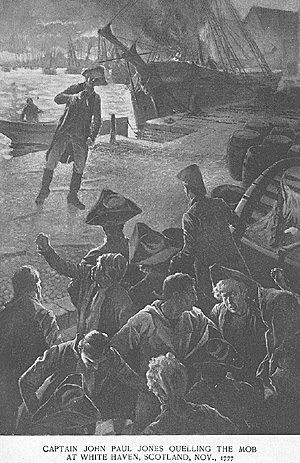

White Haven

The wind that had aided the tide in defeating Jones's enterprise blew stronger and stronger, and before morning the sea was tossing before a regular north-cast gale. Against it the Ranger could make no headway : so Jones gave his ship her head, and scudded before the wind until within the vicinity of Whitehaven, when be determined to again attempt to destroy the shipping in that port. This time he was successful. Bringing the "Ranger" to ancher near the bar, Capt Jones called for volunteers to accompany him on the expedition. He himself was to be their leader; for as a boy he had often sailed in and out of the little harbor, knew where the forts stood, and where the colliers anchored most thickly.

The landing party was divided into two boat-loads; Jones taking command of one, while Lieut. Wallingford held the tiller of the other boat. With muffled oars the Americans made for the shore, the boats' keels grated upon the pebbly shore, and an instant later the adventurers had scaled the ramparts of the forts, and had made themselves masters of the garrisons. All was done quietly. The guns in the fortifications were spiked ; and, leaving the few soldiers on guard gagged and bound, Jones and his followers hastened down to the wharves to set fire to the shipping.

In the harbor were not less than two hundred and twenty vessels, large and small. On the north side of the harbor, near the forts, were about one hundred and fifty vessels. These Jones undertook to destroy. The others were left to Lieut. Wallingford, with his boat's crew of fifteen picked men.

When Jones and his followers reached the cluster of merchantmen, they found their torches so far burned out as to be useless. Failure stared them in the face then, when success was almost within their grasp. Jones, however, was not to be balked of his prey. Running his boat ashore, he hastened to a neighboring house, where he demanded candles. With these he returned, led his men aboard a large ship from which the crew fled, and deliberately built a fire in her hold. Lest the fire should go out, he found a barrel of tar, and threw it upon the flames. Then with the great ship roaring and crackling, and surrounded by scores of other vessels in danger from the flames, Jones withdrew, thinking his work complete.

Many writers have criticised Paul Jones for not having stayed longer to

complete the destruction of the vessels in the harbor. But, with the gradually brightening day, his position, which was at the best very dangerous, was becoming desperate. There were 150 vessels in that part of the harbor ; the crews averaged ten men to a vessel: so that nearly fifteen hundred men were opposed to the plucky little band of Americans. The roar of the fire aroused the people of the town, and they rushed in crowds to the wharf.

Many writers have criticised Paul Jones for not having stayed longer to

complete the destruction of the vessels in the harbor. But, with the gradually brightening day, his position, which was at the best very dangerous, was becoming desperate. There were 150 vessels in that part of the harbor ; the crews averaged ten men to a vessel: so that nearly fifteen hundred men were opposed to the plucky little band of Americans. The roar of the fire aroused the people of the town, and they rushed in crowds to the wharf.

In describing the affair Jones writes, "The inhabitants began to appear in thousands, and individuals ran hastily toward us, I stood between them and the ship on fire, with my pistol in hand, and ordered them to stand, which they did with sonic precipitation. The sun was a full hour's march above the horizon and, as sleep no longer ruled the world, it was time to retire. We re-embarked without opposition, having released a number of prisoners, as our boats could not carry them. After all my people had embarked, I stood upon the pier for a considerable space, ye, no person advanced. I saw all the eminences round the town covered with the amazed inhabitants."

As his boat drew away from the blazing shipping, Jones looked anxiously across the harbor to the spot to which Lieut. Wallingford had been despatched. But no flames were seen in that quarter; for, Wallingford's torches having gone out, he had abandoned the enterprise. And so the Americans, having regained their ship, took their departure, leaving only one of the enemy's vessels burning. A most lame and impotent conclusion it was indeed; but, as Jones said, "That it was done is sufficient to show that not all the boasted British navy is sufficient to protect their own coasts, and that the scenes of distress which they have occasioned in America may soon be brought home to their own doors."

Chapter VII: John Paul Jones (part 2)

Back to Bluejackets of 1776 Table of Contents

Back to American Revolution Book List

Back to ME-Books Master Library Desk

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in ME-Books (MagWeb.com Military E-Books) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com