Grasshoppers have an illustrious history in the U.S. Army. They are the reason the U.S. Army had six times as many landing strips in Korea in the 1950s as the U.S. Air Force. It’s a story that goes back to 1939 and includes a scenario that seems like the plot of a Hollywood production, but was real. Fact is stranger than fiction in the story of the light planes known as grasshoppers. As we review the history, I will suggest a few rules for use of light planes in games. Then I will describe an operation that makes words like “improbable” and “far-fetched” entirely inadequate. It has the makings of a solo game that is more than a little different.

Grasshoppers have an illustrious history in the U.S. Army. They are the reason the U.S. Army had six times as many landing strips in Korea in the 1950s as the U.S. Air Force. It’s a story that goes back to 1939 and includes a scenario that seems like the plot of a Hollywood production, but was real. Fact is stranger than fiction in the story of the light planes known as grasshoppers. As we review the history, I will suggest a few rules for use of light planes in games. Then I will describe an operation that makes words like “improbable” and “far-fetched” entirely inadequate. It has the makings of a solo game that is more than a little different.

In the United States in the 1930s the Piper Cub was the most common light plane. In fact more than half the private planes in the U.S. were Piper Cubs. The Cub was a high wing monoplane. It was fabric covered, had a 65 horse power engine, and seats for two. By design it was cheap, rugged, and easy to fly. Part of the sales strategy was to make the Cub able to land and take off on any patch of level ground. If the plane needed a fancy airport, that would limit the market. To a Cub, any pasture was an airport, and anyone living nearby was a potential customer.

When World War II began in Europe, the U.S. Army began to prepare. The Piper company and other light plane manufacturers sensed an opportunity. They were also convinced that light planes could be useful to the U.S. Army. They gave the Army some planes to try out during maneuvers. During one exercise, a general needed a part from a distant supply depot. He sent out an order. “Send one of those grasshoppers for it.” Reports say the grasshopper arrived at the depot before they received the message it was coming. Commanders found they could fly over their units and untangle traffic jams. The light planes were proving very useful. The planes were being flown by sales representatives. Their instructions were simple. Give the officers rides, especially the generals. Let them fly it. Many an officer was sold by the experience. Among those early pilots was a Colonel Eisenhower.

Since this is the story of the U.S. Army, the next step was not simple. The field officers were sold, but the Army did not know where grasshoppers fit in the organization. Some base commanders could not find space for light planes. But soon they received calls from Washington D.C., and suddenly space was available.

During World War II the U.S. Army found that light planes were a very valuable tool indeed. The two most common grasshoppers were the Piper Cub and the Stinson. The Army called the Cub “L-4" and Stinson “L-5.” Unofficially these light aircraft were known as “Grasshoppers,” “Maytag Messerschmitts,” Puddle Jumpers,” “Guttersnipes,” “Doodlebugs,” and even “Little Stinky.” They were everywhere, even flying off LSTs when the army made landings on Pacific islands. They flew off a rig using towers and cable called the “Brodie device.” Of course, every road and pasture was a landing strip. Bob Hope joked, “A Piper Cub, that’s a Mustang that wouldn’t eat its Wheaties.”

During World War II the U.S. Army found that light planes were a very valuable tool indeed. The two most common grasshoppers were the Piper Cub and the Stinson. The Army called the Cub “L-4" and Stinson “L-5.” Unofficially these light aircraft were known as “Grasshoppers,” “Maytag Messerschmitts,” Puddle Jumpers,” “Guttersnipes,” “Doodlebugs,” and even “Little Stinky.” They were everywhere, even flying off LSTs when the army made landings on Pacific islands. They flew off a rig using towers and cable called the “Brodie device.” Of course, every road and pasture was a landing strip. Bob Hope joked, “A Piper Cub, that’s a Mustang that wouldn’t eat its Wheaties.”

Among the jobs they did we find: scouting enemy positions, spotting for artillery, flying officers to meetings, air dropping supplies, flying out wounded, taking commanders up to see and untangle traffic jams, and in one case, with rocket launchers strapped under the wings, taking out a tank. Mostly the light planes flew unarmed. The saying was, the firepower of a light plane doubled if the passenger carried a pistol.

The above suggests some ideas for rules. Maybe they only apply to the U.S. Army in World War II or they may apply more broadly.

- 1. In a campaign: a rule about red tape delaying use of a valuable innovation.

2. Specific rules giving bonuses in these areas to units that include light planes

- a. Scouting the enemy.

b. Artillery spotting.

c. Flying the commander where needed.

d. Evacuating wounded and raising morale.

e. Flying supplies to the troops.

Toward the end of World War II there was a great expectation that there would be a boom in light planes after the war. They would become as common as cars. It never happened. The Army shrank and the industry suffered. The U.S. Army Air Corps became the U.S. Air Force. The Air Force got the bombers and fighters. The Air Force believed these were the glamorous planes that would win the next war. The U.S. Army was allowed to keep their grasshoppers. Then in 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea. As part of a United Nations “Police Action,” the Army went to war again. They took their war weary L-4s and L-5s with them. The Air Force flew jets and got most of the publicity. The grasshoppers puttered along and did their work. Korea was so hilly the Army had to actually level off landing strips for them. They had six times as many landing strips in Korea as the Air Force.

In Korea the grasshoppers added to their legendary record. In one attack on “Heartbreak Ridge” the infantry needed flame throwers. Captain George B. Daniels of Charleston, South Carolina, flew in and dropped two flamethrowers. Soon word came out that another was needed. Captain Daniels took another flamethrower and landed next to a startled infantryman. Daniels told him “Here’s the weapon you asked for,” and took off. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Rorick Bait

Rorick Bait

But the best story of all involves a pilot named Rorick, an L-19, and a dummy named “George.” Late in the war the Army had replaced its L-4s and L-5s with the L-19, a Cessna. Rorick came up with an idea to use his L-19 as a flying rat trap. George was the bait.

Late in the Korean War the fighting was conducted along a static front. Both sides entrenched. Between the lines was contested by patrols and skirmishes. Rear area artillery was zeroed in. Near a hill known as “T-Bone Hill” the 7th Infantry Division needed some Chinese prisoners.

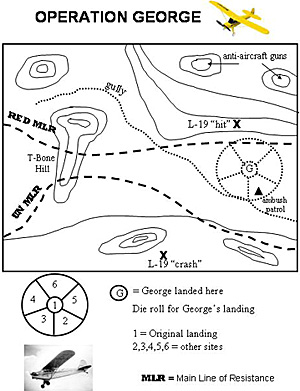

Rorick came forward with the following plan. The Chinese tried to shoot down L-19s and had 37 mm guns nearby. Rorick would fly over them and his plane would begin to smoke. The smoke would be from smoke grenades. A dummy, George, made out of sand bags for the body and shell casings for legs would bail out. The plane would fly over a hill and “crash.” The Chinese would come out to capture “George” and be met by a U.S. patrol hiding nearby. Such was the plan as approved.

February 1953, it happened. The patrol moved into position near the drop zone under cover of darkness. All day they stayed hidden waiting for the L-19. As dusk was falling, Rorick flew over. The Chinese opened fire and Rorick activated the smoke grenades. George bailed out but the winds were strong and he was blown away from the intended landing zone. Then several things happened at once.

A Chinese force started for George. The L-19 flew over the hill and the “crash” was staged, producing realistic-looking fire and smoke. The American patrol began a frantic move to intercept the Chinese. A staff officer was observing the operation in the gathering darkness. He called in division artillery and they laid a line of shells on the Chinese. The Chinese retreated and never returned. George lay there for hours. About midnight the American patrol returned to their lines. Operation George was a failure, but what a scenario!

Let’s look at this as a wargame starting with the land forces involved. The American patrol was about a platoon, as nearly as I can figure out. In 1953 a platoon consisted of about 30 men commanded by a lieutenant, a platoon sergeant, and three sergeants as squad leaders. Each squad had nine men. Most men would be armed with the M-1 Garand Rifle, an eight-shot semi-automatic rifle. Each squad would also have a BAR, a twenty-pound light machine gun with bipod that that used 20-round magazines. In addition, the men would carry pineapple style grenades like those used in World War II.

The Chinese force and weapons would be different. Does it surprise you that we will dice for their numbers? They would be using burp guns. This is an ugly submachine gun that shoots in short bursts that sound like “burp.” It is fed from a round disk magazine. Most men would not carry these. Instead they would have a supply of grenades. These are designed like potato mashers much like the WW II German grenade. It was routine for U.S. troops to throw these grenades back before they exploded. If they go off nearby they are damaging, but not lethal.

I suggest that we dice for the place where George lands and for the division artillery - if any. I have provided a map and chart. Roll a D-6 to determine where George lands. Assume the Americans will move to intercept the Chinese. Dice for Chinese forces. Roll a D-6 and multiply by 10. To determine how many Chinese carry burp guns, roll a D-6 and add it to your first roll.

Do this after the Americans have their orders. Roll a D-6 to determine if the artillery fires: a 5 or 6 means they will. Then roll again: 1 or 2 means they hit the Chinese, 3 or 4 means they land between the forces, and 5 or 6 means they hit the Americans. I’m sure any SWA members can develop rules for further complications in this scenario.

Bibliography

Francis, Devon Earl. Mr. Piper and His Cubs. (1973).

Kortsgaard, Bert. “Korean War, History, Weapons, Combat Photos.” www.rt66.com/korteng/smallarms/anms.htm.

Politella, Dario. Operation Grasshopper. (1958).

Ten Eyck, Lt. Col. Andrew. Jeeps in the Sky: The Story of the Light Plane. (1946).

Back to Table of Contents -- Lone Warrior # 145

Back to Lone Warrior List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Solo Wargamers Association.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com