During the 14th and early 15th centuries three widely separated developments; the Swiss pikemen, the English archers, and the wagon fortress tactics of Jan Ziska and the Hussites of Bohemia — led to the decline of armoured cavalry as a dominating force on the battlefield. Their long supremacy was broken by steady, disciplined infantry armed with a combination of missile and shock weapons such as longbows, handguns and pikes.

During the 14th and early 15th centuries three widely separated developments; the Swiss pikemen, the English archers, and the wagon fortress tactics of Jan Ziska and the Hussites of Bohemia — led to the decline of armoured cavalry as a dominating force on the battlefield. Their long supremacy was broken by steady, disciplined infantry armed with a combination of missile and shock weapons such as longbows, handguns and pikes.

In fierce warfare, Sigmund’s vastly superior forces of German knights of the Holy Roman Empire was repeatedly defeated by tactics two centuries ahead of their time, victories that owed much to the genius of one-eyed Jan Ziska. He towers above the military thought of’ the age as the first commander to use armour-protective fire power as a manoeuvrable arm in a technical combination of cavalry and infantry as a mobile defensive/offensive system, employing the modern concept of movement in armoured personnel carriers. Ziska noted the effectiveness of Russian and Lithuanian wagon laagers in defense against Tartar, Polish and Teutonic Knight cavalry. He also noted that the wagon defenders were lost if a combined cavalry and infantry attack could penetrate the laager. From this lesson he developed one of the simplest and most effective tactical systems in history.

Wargaming the Hussite wagon-forts presents many novel and simulating features. The wagons themselves, suitably scaled so as to be capable of carrying a crew of handgunners, must be scratchbuilt from plastic card or balsa wood, etc. In an odd sort of way, rules governing their use bear a great resemblance to some of the more elementary methods of handling tanks and APCs of a much later date!

At his fortress base of Tabor, Ziska trained his followers, transforming them from poorly equipped, untrained peasants, who knew nothing of crossbows or handguns and had never been in battle, into a well trained and balanced fighting force that, while never exceeding 25,000 men, defeated armies up to seven or eight times their own numerical strength. The knights and infantry of these vast armies wore armour that resisted both arrows and crossbow bolts at normal battlefield ranges, so Ziska armed one third of his infantry with the handgun.

The Hussite Wars were religious struggles and the strong beliefs that they valued more than their lives together with a high degree of nationalistic fervour, gave the hymn-singing Bohemian peasants an almost fanatical enthusiasm. Demanding from both officers and men the utmost discipline and devotion, Ziska trained his force into a unique combination, enforcing harsh laws and introducing vigorous but controlled conscription to provide manpower for his army

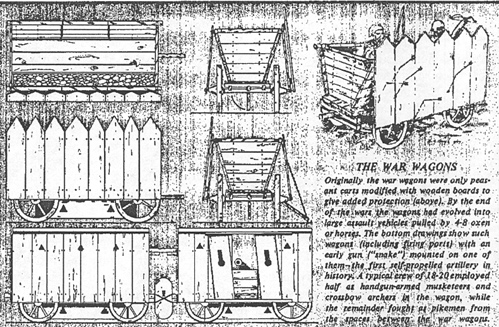

Over and above all these qualities, the Hussites evolved a new weapon system by adapting the wagon-fort as a tactical unit and revolutionised warfare by new concepts of firepower and manoeuvre. A factor in the Roman defeat by the Goths at Adrianople in 378 AD, the wagon-laager had been used as a maneuverable fortress for centuries by migrant tribesmen. It was employed as a defensive barrier to protect its occupants from attack, much in the manner of the Western settlers against Red Indians/Native Americans. After early victories, Ziska discarded his improvised wagons and constructed wheeled forts designed specifically for fighting. These medieval predecessors of the tank were built of solid heavy slabs of wood reinforced with iron and leather, their chest-high sides pierced with slots for firing bows and handguns and fitted with chains to link them together when under attack. Each wagon was a unit, crewed by twenty men - ten musketeers who fired from inside the wagon and ten pikemen who defended the space between the wagons. There were wagons and carts mounting medium and heavy artillery such as rock-throwing catapults and iron cannons firing stone balls,

At first the wagons did not actually attack but moved into position and then were chained together to form forts, still sufficiently mobile to be quickly hitched up. Ziska believed that they could also be effectively utilised in offensive operations, and soon his wagoners were so highly trained that the heavy draught-horsedrawn wagons could advance to the attack in a series of parallel columns; they could form squares or rectangles, circles or triangles at a given signal, and under virtually all conditions. At their peak, the Hussites were so adept at mobile warfare that they could take their wagons into the midst of an attacking army before forming their battle line.

At that time, the Hussite army was formed of two-thirds wagon-fort troops armed with handguns and pikes, and one-third light cavalry armed with lances and crossbows. If Hussite tactics had a major defect it was that they lacked cavalry to exploit a victory, although Ziska did have a body of highly trained horsemen who rode with his combat wagon trains, most of them were mounted crossbowmen capable of reloading their weapons and remaining mounted. These Hussite mounted archers acted as light cavalry, scouting and skirmishing and pursuing when necessary. In a pitched battle they took refuge in the wagon-forts and added their fire to that of the crews.

Well in advance of their time and anticipating a new age of tactics, the Hussites’ style of warfare was never really comprehended by their foes who saw them in an aura of invincibility which often saved the Hussites the trouble of fighting a battle. Lacking the ability to enforce discipline, opposing commanders could not keep a fighting force in the line to stand up against the Hussites, but in time their adversaries took advantage of the Hussites’ well known zeal in counterattacking and used it to the their advantage by feigning retreat so that the Hussites abandoned their battle formations and pursued. Then, shorn of their armoured protection, they were cut off from their primary weapon system and defeated, for without their wagons the Hussites were no match for the overwhelming numbers of their enemies. The armies of the Catholic Knights were often over 100,000 strong, formed of one-third heavy cavalry consisting of mounted knights armed with lance and sword, one-third heavy infantry formed of nobles and men-at-arms with the pike and sword, and one-third peasants who were mostly poorly armed light infantry and included a few archers.

Wargames Armies

Wargames Armies

When building up wargames armies to fight in this period, balanced armies can be selected by allotting points values to the various types of soldier and weapon used by both armies. The following suggested values are intended to demonstrate their varying potential:

Peasants — 1 point

Dismounted Catholic Knights (men-at-arms) - 3 points

Mounted Catholic Knights - 5 points

Hussites Pikemen - 5 points

Hussite handgunner (in wagons) - 5 points

Hussite mounted archers — 6 points

Hussites wagons (with 4 horses) - 120 points

Extra horses - 15 points each

Hussite guns - 50 points

Additional horses will give extra speed (a greater move distance) to the Hussite wagons whilst prolonging: their mobile existence during combat. When formed up in a defensive laager, the wagons are considered in the same light as a defensive position, such as a house or earthworks affording protection to its defenders. But when hitched-up to their horses the wagons have a ‘vulnerability’ value. Points are given to represent the effects of weapons, such as 5 points for an arrow striking home on a horse, so that a mounting score of such points will reduce the mobility and effectiveness of the wagon and its crew. Thus:

- 15 points - 1 horse killed, reduces move distance of wagon by 20%.

30 points - 2 horses killed, reduces move distance of wagon by 50%.

45 points - 3 horses killed, reduces move distance of wagon by 75%.

60 points - 4 horses killed, wagon is stationary.

This table will be adjusted in the event of the wagon having six horses. Should the wargamer attacking the wagon desire, the points can be scored against the wagon crews or even the wagoner himself.

The victorious ability of the Hussites lay in disorganizing the enemy by the inherent armour-protected firepower of their vehicles, and then following up with a powerful counter-attack. The usual Hussite battle formation consisted either of one of the well rehearsed geometric configurations or a battle line of wagon-forts across the front, with pikemen or artillery in the gaps and cavalry on the wings. The battle began with the Catholic heavy cavalry, goaded by missiles from catapults and by the skirmishers, surging forward to the attack, assailed with missiles from the bombards and by the handguns at close range. This high rate of firepower usually halted the attack, but on the rare occasion when the remnants of the cavalry actually came up to the wagons, they were unable to penetrate further because of the armoured walls and the stands of pikes in the intervening spaces. Pikemen were available to protect the bombards and to prevent enemy infantry from cutting the chains holding the wagons together. They rarely had to perform these missions, however, since the attackers were more often than not repulsed by the firepower of the wagonberg.

When the frustrated and sorely stricken enemy began to withdraw, the Hussites launched a counterattack, chasing the retreating cavalry back to their own advancing infantry, causing confusion and dismay. Then the wagons were unchained to take up an offensive formation, which thundered across the battlefield, their crews firing throughout while the Hussite cavalry harassed the enemy flanks. There was no quarter neither asked nor given.

Such tactics required well-disciplined and confident troops, even though the Catholic knights fought to rigid feudal ideas and lacked co-coordinated strategy.

Typical Hussites victories included Prague in 1419, when they repelled a frontal attack from an entrenched position on a hill beneath the city walls with their guns sited so as to give a destructive crossfire; at Kuttenberg in 1422, the wagon-laager stopped the German frontal attack and then Ziska pit in a furious counter-charge with mobile artillery support to destroy the enemy; in 1426, after Ziska’s death, the Hussites under Prokop defeated the Germans at the Battle of Aussig, breaking up their formations by a strategic wagon attack and then a cavalry charge into the disordered ranks. In their time the Hussites fought in Hungary, Austria, Silesia, Saxony, Bavaria, Thuringia and Franconia. After Ziska’ s death, Bohemia split into two opposing groups and. Ziska’s commanders divided amongst themselves, forgetting the true strength of their tactical concept.

With the specific aspects of this unique type of warfare handled by suggestions contained in this article, the game can be controlled by any recognised set of rules for the period. The ‘thinking’ wargamer can make himself the scourge of the medieval tabletop battlefield, to cries of: ‘Not those damned wagons again!’ But, he will have to truly appreciate and assess the battle-power and strength of his integrated combat- team, which will be based on mobility and armour-protected firepower, while honestly recognising its limitations.

[Historical note: Ziska lost his other eye during a siege and although completely blind directed his future operations through the eyes of his subordinate commanders, combined with his intimate knowledge of the terrain. He died on 12 October 1424 having been victorious in 11 major and numerous minor campaigns and his troops never suffered a defeat under his generalship.

Wargamers note: How many of us could fight a battle with Ziska’s handicaps? Kenn]

Back to Table of Contents -- Lone Warrior # 143

Back to Lone Warrior List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by Solo Wargamers Association.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com