[originally published in LW 79]

Introduction

One aspect of campaigning that gets little or no attention is the feeding of an army’s horses. Many wargamers reflect the rise and fall of their armies’ food and ammunition supply, but our metal and plastic steeds seem to just go on forever.

Why bother to introduce yet another complication to interfere with the business in hand, i.e. pushing our soldiers around the table? A gross over-simplification of what we do, I know, but sufficient for the argument. The reasons are straightforward. Armies need horses not only to carry the cavalry and artillery into and out of battle, but also to drag the carts containing the food, ammunition, tents, plunder, indeed all the things necessary for an army’s existence.

Background

In the period ranging from the end of the 17th century to the middle of the 18th, an army’s ability to function effectively was in proportion to the amount of fodder available to its horses. Problems arose because armies still used single lines of operation and had not developed the concept of moving and subsisting in a number of widely separated columns, concentrating only to fight. A brief illustration might help clarify the extent of the problem. Armies needed double the amount of fodder rations as they had cavalry horses. Therefore, an army with 20,000 cavalry would need 40,000 rations per day during the campaigning season. [1] It has been calculated that to carry this amount of fodder, 1,000 carts would be required, and at 12 metres per cart (with a full team and adequate space between each cart) you end up with an army having a very long “tail.” [2] Note we have yet to add all the men’s bread wagons, the ammunition wagons and the general’s coaches and baggage wagons!

There are also strategic aspects to this. In all campaigns there are times when little or nothing appears to be happening. This to a great extent is due to armies wishing to “eat out” an area, creating a barrier over which the enemy was unable to pass without preparation. Such preparations could not go unnoticed, and so any surprise would be lost. [3]

For example, after the Battle of Hohenfriedberg (1745), instead of carrying out a strategic pursuit of the defeated Austro-Saxon army, Frederick the Great restricted his operations to the systematic exhaustion of the area forming the border between Bohemia and Silesia, thus making Silesia safe for the rest of the Second Silesian War.

[4]

Now before you swear-off “horse and musket” campaigns forever, let me put your minds at rest. Whilst an army is on the move, the question of how it’s horses are to be fed doesn’t arise because as it goes forward it continues to meet “fresh” pastures. [5] It is only when it stays in an area for any length of time that problems occur, and areas become “eaten-out.”

Mechanics

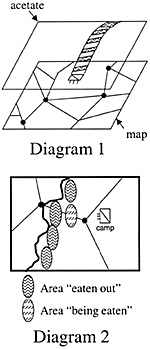

The use of acetate and markers or chinagraph pencils to show the passage of an army over the map is “old hat”. However, by hatching the area passed over (see diagram 1) you show it can still provide fodder. When the army, or another passes over that way, more hatching is done, until the area is filled in. An alternative use of florescent pens might be to have different colors and when the mix of colors becomes too dark, the area cannot sustain an army. Rules for re-growth are a matter of guesswork, the rate of growth being weather dependent, but my lawn becomes unmanageable within about two weeks of being mowed. This is probably far too short a time in reality but it does provide a guide. Perhaps there is a reader who owns a horse and a field who could supply some “raw data”?

When one army proposes to eat out an area, you simply calculate the area that can be “occupied” by an army’s horses and, when foraging, mark the area on the acetate, hatching as necessary. An oval would probably approximate the shape of such an area, though in reality, the outline would be fixed by its resources and the proximity of the enemy. Close proximity, the norm during the majority of a campaign, would increase the need for security and decrease the number of horses available for the operation. As a general point there was an order in which areas were foraged. That part nearest the enemy would be done first, those parts to an army’s own flanks next and finally those to the rear - as the army fell back. (See diagram 2). To calculate the area “occupied” by the horses you need the following information

Note

Sources

[1] Chandler D. The Art of Warfare in the Age of Marlborough, (Batsford Ltd. 1976) p. 17.

Clearly then, most of the fodder had to be collected on the spot, not in a haphazard way, rather in an ordered and systematic manner to reduce the chances of desertion and for interference by the enemy. Forages thus became elaborate affairs effectively surrendering any initiative to the enemy. However, they were not entirely passive operations. They could, and frequently were, used very aggressively. An excellent example is William III’s attack against the French at Steenkirk (1692) when the movement of William’s army was dismissed as a “grand forage,” albeit at the prompting of a spy William had planted in the French camp. That the movement of a large number of men could be dismissed in such a manner, shows how much a way of “army life” it was in our period.

Clearly then, most of the fodder had to be collected on the spot, not in a haphazard way, rather in an ordered and systematic manner to reduce the chances of desertion and for interference by the enemy. Forages thus became elaborate affairs effectively surrendering any initiative to the enemy. However, they were not entirely passive operations. They could, and frequently were, used very aggressively. An excellent example is William III’s attack against the French at Steenkirk (1692) when the movement of William’s army was dismissed as a “grand forage,” albeit at the prompting of a spy William had planted in the French camp. That the movement of a large number of men could be dismissed in such a manner, shows how much a way of “army life” it was in our period.

Calculating how much fodder is required need not concern us. What we are seeking to reflect is the passing of an army across a given area, and its effect on the amount of fodder available. Some creative guesswork is needed about how long an army can remain in an area before the horses need to go beyond the immediate area for fodder. It also seems sensible to assume enough pasture or crops would remain after the horses had passed for it to begin growing again. Therefore, it is not enough to score through a map to show an army had passed that way. We need to show the gradual reduction of an area. The nicest thing about it is that it is a situation that cannot be hidden from a commander (he may ignore it) and, therefore, can be simply and graphically displayed. This alone makes it beneficial to soloists. By the use of very simple rules, plus florescent markers and sheets of acetate (or tracing paper or photocopies) the mechanics and irritation are kept to a minimum.

Calculating how much fodder is required need not concern us. What we are seeking to reflect is the passing of an army across a given area, and its effect on the amount of fodder available. Some creative guesswork is needed about how long an army can remain in an area before the horses need to go beyond the immediate area for fodder. It also seems sensible to assume enough pasture or crops would remain after the horses had passed for it to begin growing again. Therefore, it is not enough to score through a map to show an army had passed that way. We need to show the gradual reduction of an area. The nicest thing about it is that it is a situation that cannot be hidden from a commander (he may ignore it) and, therefore, can be simply and graphically displayed. This alone makes it beneficial to soloists. By the use of very simple rules, plus florescent markers and sheets of acetate (or tracing paper or photocopies) the mechanics and irritation are kept to a minimum.

This piece has been drawn from the sources given below. The most close examination of the whole question of logistics in this period is that of Perjes’. I would strongly recommend anyone with even only the slightest interest in logistics and its place in warfare to read his article. He talks of only a cursory survey (in an article of 51 pages) but it is surprisingly complete and its relevance goes beyond the period covered in the title. The article is published in a Hungarian journal so you will have to obtain a copy through the inter-library loan service.

This piece has been drawn from the sources given below. The most close examination of the whole question of logistics in this period is that of Perjes’. I would strongly recommend anyone with even only the slightest interest in logistics and its place in warfare to read his article. He talks of only a cursory survey (in an article of 51 pages) but it is surprisingly complete and its relevance goes beyond the period covered in the title. The article is published in a Hungarian journal so you will have to obtain a copy through the inter-library loan service.

[2] Perjes G. “Army Provisioning, Logistics and Strategy in the Second Half of the 17th Century” (Acta Historica Academia Scientiarium Hugaricae 16, 1970) pp. 14-19.

[3] Duffy, C. Frederick the Great: A Military Life (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1985) pp. 305-306.

[4] Ibid, pp. 66-67.

[5] van Creveld, M. Supplying War: Logistics from Wallenstein to Patton (Cambridge University Press, 1977) p. 34.

Back to Table of Contents -- Lone Warrior #137

Back to Lone Warrior List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Solo Wargamers Association.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com