As I read more about the American Civil War in the West (west of the Appalachian Mountains), I was struck by the primitive nature of the transportation network. The primary routes were the rivers. These were supplemented by railroads and roads of various but generally poor quality. The roads and trails extended from the waterways (ports, bridges, fords, ferry crossings) deeper into the interior. Other roads paralleled the rivers when the terrain permitted. Fairly rich in navigable waterways, the land in the west was road poor. The good land was cleared and settled by yeoman farmers and some larger plantations but most of the land was still forested.

As I read more about the American Civil War in the West (west of the Appalachian Mountains), I was struck by the primitive nature of the transportation network. The primary routes were the rivers. These were supplemented by railroads and roads of various but generally poor quality. The roads and trails extended from the waterways (ports, bridges, fords, ferry crossings) deeper into the interior. Other roads paralleled the rivers when the terrain permitted. Fairly rich in navigable waterways, the land in the west was road poor. The good land was cleared and settled by yeoman farmers and some larger plantations but most of the land was still forested.

Absent were good maps, a fact which complicated the movement of some fairly large armies. Battles were fought to control the rivers and rail lines and some of the largest battles (Shiloh and Chickamauga for example) were fought in the midst of heavily wooded terrain. I wanted a methodology that would generate terrain as it unfolded to simulate the problems of command and control in the western theater.

In the following case, the soloist represents a union division commander. He owns three brigades of four infantry regiments each and an artillery battalion of three batteries. He rolls to assign strengths and morale for each unit. His mission is to cross a river upstream from his parent corps and support the corps' attack on the enemy believed to be on the east side of the river and moving to build a defensive line along the river. His commander wants him across the river before the end of the day.

Once across the river, he must form his division into a column heading south on a road running parallel to the river. The terrain is rolling forest cut by a single road, numerous trails, and marked from time to time by farm fields. The road leads to a wooden bridge across the river. There are two fords, one upstream and one downstream from the bridge. Maps are unavailable and the locals have fled the area. No one is quite sure where the trails lead but the common consensus is that they probably connect the farms and fords to the main road somehow.

Once across the river, he must form his division into a column heading south on a road running parallel to the river. The terrain is rolling forest cut by a single road, numerous trails, and marked from time to time by farm fields. The road leads to a wooden bridge across the river. There are two fords, one upstream and one downstream from the bridge. Maps are unavailable and the locals have fled the area. No one is quite sure where the trails lead but the common consensus is that they probably connect the farms and fords to the main road somehow.

What's He Know?

Okay, what does our division commander know? He understands his mission and he knows the forces he commands. He knows very little about the terrain and nothing about the enemy except his intentions in very broad terms (to defend along the river). What doesn't he know? He doesn't know where or when he will meet the enemy or the size and disposition of the enemy force. He doesn't know the terrain beyond the visual range of his foremost soldier. The solo gamer now looks to mechanisms which will provide these answers as he needs them. Let's talk terrain first.

The solo gamer considers the terrain features he wants to simulate. He believes that the road leads to a bridge. However there are bends in the road which conceal what is beyond the bend. He wants to limit his knowledge of what is around the bend until he puts a set of eyeballs there. The ground is covered in forest, sprinkled with farm fields, and cut by trails. Our gamer wants the trails to unfold like the road - from bend to bend. He wants to come upon farm fields at random along the road and the trails.

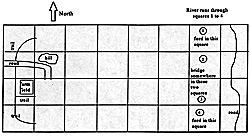

Lastly, he wants swells in the land - gently sloped, tree-covered hills on both sides of the trails and road which block vision of what is beyond and provide suitable defensive positions for any enemy bold enough to venture to "our" side of the river. The following map depicts what the division commander "knows" at the start of the game. The map depicts a 4 x 8 board. Squares are 1 x 1. The only areas which are not covered by woods are the farm fields, road and trails, and open areas on both sides of the bridge and fords.

Enemy

Let's discuss these enemy fellows. Putting ourselves in the mind of the confederate commander we can expect him to be doing two things. First, he will have recon elements trying to find the Yankees so he can figure out what they are up to. Second, he will want to defend the possible crossing sites along the river as well as have forces beyond the river to cover the approaches to the bridge and ford. And if he is a stellar commander, he may be planning a brilliant pre-emptive attack to defeat the federal forces on the west side of the river while they are strung out approaching the crossing sites.

So our solo gamer has his hands full. While he will want to secure his force by seizing hills along the road, he must also move his force quickly. This means he may want to move some forces along the trails or even cross-country and use the fords as well as the single bridge. There is no time to scout out the road and the trails before the division moves. He must do this while the bulk of his forces are moving.

Brigade at a Time

The solo gamer decides to send a brigade down the road and on two of the trails. Each brigade will be led at some distance by an advance guard regiment, each regiment by an advance company. He will feed in the lead regiments of each brigade first so that the heads of all columns are on the game table before feeding in the remainder of the brigades. He decides to put a battery with each brigade behind the second regiment in each column.

As you can see, by feeding troops onto the table one regiment at a time, the brigade columns will become strung out with gaps between regiments. The soloist issues the march order for the entire division before the game begins. The troops remain off board until their turn in the march order arrives. Visualize the road off board crammed with troops moving slowly toward the game board. The commander can't adjust the order of march without paying a penalty in lost time because the order must be sent off board to the unit concerned and other regiments must leave the road to let the selected unit forward.

Bend in the Road

Bend in the Road

As the advance companies come to bends in the roads, the soloist rolls a die to determine what they find both in regard to terrain and the enemy. He places the newly discovered terrain on the next square, building the map as the game progresses. The soloist is constrained to the game table. If a trail leads off the board, the troops can not follow but must either head back or strike out cross-country.

If the commander decides to move cross-country, when he enters the next square he picks up a trail heading east which bends in the middle of the square. Trails are wide enough for a single unlimbered cannon; the road can accomodate three guns across. If you enter a square with terrain already in place, integrate your newly-determined terrain with that which is already there. When a trail approaches another trail or the main road, roll to see whether it terminates or if the two run alongside for awhile.

These are the basics. Discovery occurs as the lead elements round the bend. There are any number of mechanisms to roll a die or two to generate what it is that you discover. Let me offer a few samples. Okay, one of your advance guard companies arrives at a bend in the road. For our example roll 1D6 for terrain and 1D20 for enemy activity. The following tables are suggestive of the kinds of results you may want in your rules.

| Die roll | Terrain Result |

|---|---|

| 1 | Trail or road turns north (if already heading north or south, it turns east). Field is adjacent to trail or road. Roll for placement of field left or right of trail. |

| 2 | Trail or road turns east (if already heading east roll die for turning left or right).Farmers field is adjacent to trail or road. Roll for left or right of trail. |

| 3 | Trail or road turns south (if already heading south or north, it turns east).Hill is adjacent to road; roll for left or right. |

| 4 | If on a trail, it leads to farmer's field and stops. If on the road, it turns or continues east. There are open fields on both sides of the road. |

| 5 | Trail or road splits, one branch goes east, the other heads toward the center line of the board. There is a hill in the fork of the road or trail. |

| 6 | Trail or road turns east (if already heading east roll die for turning left or right).Hill is adjacent to trail or road; roll for left or right of trail. |

If you enter squares 1 or 4, roll to learn about the ford.

| 1,2 | The river is 3 inches from west edge of square and the river is 3 inches wide. The land is clear for 3 inches around both sides of the ford site. Roll for enemy. |

| 3 | The river is 6 inches from west edge of square and the river is 3 inches wide. The land is clear for 2 inches around both sides of the ford site. Roll for enemy. |

| 4 | The river is 6 inches from west edge of square and the river is 2 inches wide. There are farmer's fields on both sides of the ford site. On the near side of the ford the trail turns toward the bridge. Roll for enemy. |

| 5 | The river is 3 inches from west edge of square and the river is 3 inches wide. The land is clear between you and the river. There is a treeless hill directly across from the ford. Trail continues around hill to the right. Roll for enemy. |

| 6 | The river is 3 inches from west edge of square; the river is 4 inches wide. The land is clear for 3 inches around both sides of the ford site. The water is too rough for the battery's horses to cross and the banks too muddy to get the guns into the water. |

If you enter squares 2 or 3, roll to learn about the bridge.

| 1 | The river is 3 inches from west edge of square and the river is 3 inches wide. The land is clear for 3 inches around both sides of the bridge site. Roll for enemy. |

| 2 | The river is 6 inches from west edge of square and the river is 3 inches wide. The land is clear for 2 inches around both sides of the bridge site. Roll for enemy. |

| 3 | River is 3 inches from west edge of square; the river is 4 inches wide. The land is clear between you and the river. There is a long treeless ridge directly across from the ford. Trail splits left and right at the base of the ridge. Roll for enemy. |

| 4 | Bridge is not in this square; it is in the other square. The road turns toward the other square. Disregard if you have already been in the other square; use result 1. |

| 5 | Bridge is not in this square; it is in the other square. The road turns toward the other square. Disregard if you have already been in the other square; use result 2. |

| 6 | The river is 2 inches from west edge of square and the river is 3 inches wide. The land is clear for 3 inches around both sides of the bridge site. The bridge guards have spotted you and are even now torching the bridge. If you attack immediately, you have a 60% chance of putting out the fires before the bridge becomes unusable. You can not ford the river here. Roll for enemy across bridge. |

This table is a place to begin when constructing a table for enemy activity. Use 1D20.

| 1-12 | No enemy seen. |

| 13-14 | Cavalry troop on road or trail heading toward you, 3 inches away. |

| 15 | Three companies of infantry across road 4 inches away. If field nearby, two more companies at far side of field. |

| 16 | Enemy gun on road or trail 6 inches away backed up by four companies infantry. |

| 17 | Five companies block road or trail 5 inches away. |

| 18 | Ambush! Two companies infantry open fire from point blank range. |

| 19-20 | Lead company sees no activity. However, next unit in column is attacked by five companies of infantry! |

Because you may only see a fraction of the enemy at first, after you make contact you will roll again to see what else he has there to confront you.

| 1 | 3 more companies of infantry appear on your flank. Roll for left or right flank. |

| 2 | Regardless of battle results thus far, enemy recoils and withdraws out of sight. |

| 3 | Holy cow! Entire regiment of infantry backs up the group you ran into initially. Roll again on this table next turn. |

| 4 | Enemy backed up by 2 troops of cavalry. Roll again on this table next turn. |

| 5 | Enemy backed up by a number equal to that first encountered. |

| 6 | No more enemy encountered other than those you are now in contact with. |

There you have it - a concept of how a soloist might design a game that is entertaining and challenging and simulates a typical situation encountered in the American Civil War.

Back to Table of Contents -- Lone Warrior #118

Back to Lone Warrior List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by Solo Wargamers Association.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com