This article describes methods of creating tactical problems which can be fought out on the wargames table, and how to fit them together to simulate an ongoing campaign. Players in other periods may get a few ideas from them but they have been developed and used in the mechanized period, by which I mean the time from the invention of the tank and the first use of mechanized forces, up to the present day. This includes the Korean War; the various Arab-Israeli clashes; Vietnam; the Modern period - which seems to be attracting a lot of players nowadays - and of course, World War Two.

This article describes methods of creating tactical problems which can be fought out on the wargames table, and how to fit them together to simulate an ongoing campaign. Players in other periods may get a few ideas from them but they have been developed and used in the mechanized period, by which I mean the time from the invention of the tank and the first use of mechanized forces, up to the present day. This includes the Korean War; the various Arab-Israeli clashes; Vietnam; the Modern period - which seems to be attracting a lot of players nowadays - and of course, World War Two.

I will attempt to illustrate my ideas with special reference to W.W.II - mainly because I know next to nothing about the other periods! W.W.II has its own special problems, in that it was a period of continuous and rapid military development, and armies changed their equipment and organization several times. This may explain to the uninitiated why a player might describe his army as, for example, '1942 British' rather than 'W.W.II British'. Organization was as important as the standard of equipment, especially if the combatants were to make the best use of their mobile forces. Early in the war the German command structure was more suited to mobile warfare than that of the Allies, who learned rapidly and adjusted their formations to the task in hand.

The war can be divided into various spheres of action: the German victories of 1939-40; the Western Desert and North Africa; Italy; Western Europe after D-Day; and the Russian Front. Each of them posed their own tactical problems. Looking at Russia, the scale of the fighting makes it extremely difficult to simulate in a campaign. In 1944 Germany had over 3 million combat troops deployed in the east, not including supply and replacement personnel or the Luftwaffe. Against them the Russians had over 6 million. These were deployed on a front which stretched from the Gulf of Finland to the Caspian Sea; from one climatic extreme to the other, a distance of over 1200 miles as the MIG flies.

Although other fronts were shorter and less troops were involved the main difficulty is in representing large-scale combats on the wargames table. There isn't enough room to deploy a complete division unless you are prepared to use a representative troop scale and a streamlined set of rules. And there are also those who prefer company level engagements using 20-25mm figures: presumably they would like to campaign too, on occasions. In addition, the modern campaigner has a lot to worry about.

While his ancient counterparts get by by providing food for their troops and fodder for their animals, the demands of a mechanized army are much more sophisticated. Petroleum products, engine and equipment spares, POW's; ammunition in upwards of a dozen different calibers - and that's just a few examples. I doubt whether any wargamer wants to get involved in these complications. What the soloist needs is a simpler method, one which places maximum emphasis on front line combat troops and ignores the rear echelon and support units.

Object

The usual object of a campaign is to produce a series of battles with some common linking factor. Usually this is the fact that the troops involved represent the entire military strength, in one or more armies, of a nation's military might; but for mechanized campaigns I use a different denominator.

Instead of the wargamer deciding his own strategy, these orders come to him from his 'High Command' in the form of a few dice throws, and it is then up to him to carry them out using whatever tactics he sees fit. The results of this battle help to decide the overall success of the army of which the player's forces are a part. In general his success should help ensure the success of his army: if he gets it wrong. . . .well. The army commander, 'High Command', or whoever his superior happens to be, can then send him a new set of orders, forming part of the army's new strategy, or a continuation of its old one. And so it goes on, for as long as the player has the stamina.

The scale of the game depends on what models etc. you can field. Someone who plays 1:72 infantry actions could represent a company commander, whereas the 1:300 player could conceivably field a division on the tabletop. There is one snag with all this: before you can start you have to sit down and pre-program your 'High Command'. I expect everyone is familiar with the numbered paragraph system: a good example is the 30 Years War solo by Andy Callan (LW 30). Basically the player is confronted by a decision, and depending on his response he is directed to another section which reveals the results of his choice, and leaves him another decision to make. This goes on until a final decision is reached. Now I don't propose that everyone should go through the time consuming procedure of reducing their 'High Command' to this format, since a clearer and quicker method is to use a flowchart.

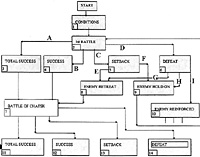

Flowcharts will be familiar to those who know something about computer programming. Basically, a flowchart represents a process from start to finish, with all the decisions that must be made in between. The alternative choices of each decision are represented by branching paths in the flowchart, each of which may lead to their own alternative ending. All this sounds highly complicated, but once you try it, it is really quite straightforward, and the simplest thing to do is to give an example.

Have a look at the flow chart. If you follow the arrows downwards from the start, the first box (marked 1) explains the conditions at the start of the campaign, and the objectives of the force under the player's command.

Have a look at the flow chart. If you follow the arrows downwards from the start, the first box (marked 1) explains the conditions at the start of the campaign, and the objectives of the force under the player's command.

Example: "Friendly forces have smashed through the enemy lines and fast mechanized formations are striking deep into their rear areas. You are part of such a group. Your immediate objective is the town of Chatsk, and the bridges over the River Zandroi, which must be held until relieving forces can arrive. At this point you should select your own force and its supporting units"

When these objectives are taken the campaign is ended, though if the player wishes there is no reason why it could not continue. Selection of suitable forces is a problem on its own, since the player has to make them suit the terrain and also the strategic objectives. An unsupported tank battalion would not find street fighting in Chatsk the most healthy of occupations! Later I'll explain how to use a random factor to decide how many supporting units 'High Command' would assign to you. We now follow on to box no. 2, in which we meet the first opposition.

You can choose the composition of the enemy force yourself or use a random method to determine it. In this particular scenario its tactics are most likely to be a dogged defense, but watch out for armored units which may launch counter-attacks. Anyway, you now have a battle to fight and have the problems of breaking through but still keeping casualties low enough for the next stage. When you know the result, you can select the branch which takes you to your next instructions, most of which flow logically in the course of events, and are detailed in boxes 3 to 6.

In the two cases where you are successful, the length of time the battle lasts will determine how many troops the enemy have managed to pour into Chatsk, and might be arranged as a certain points value per period, chosen at random. Also troops from the defenders have not been routed. Therefore in case (4) a throw of 3,4,5,6 for each unit in rout at the end of the battle, make it back to Chatsk. In case (3) the greater speed of your advance and the loss of cohesion in the enemy forces might allow the non-routers to make it back on a throw of only 5 or 6. Normally all these details would be included on the flowchart: I haven't bothered because I'd only be repeating myself. Anyway, both these results lead on to the battle for Chatsk itself (box 7).

No Success?

What if you aren't successful? Well box (5) might read like this: "Message from High Command: 'Your failure to break through has jeopardized the success of the entire campaign. It is vital that you resume your attack without further delay. The Zandroi bridges must be taken as soon as possible.' ".

A well deserved verbal barrage? If High Command is feeling generous he may decide that you deserve some reinforcements (an unlikely occurrence) this being decided by the ever-useful dice throw. However the enemy will not have been inactive while you have been licking your wounds. They have two options; try and hold the forward defenses against you next attack, or fall back to Chatsk content with the delay they have inflicted. A dice throw of 1,2,3,4 might select branch (e) in this case.

In box (6) the consequences are worse. After such a great victory the enemy will not be in such a hurry to retreat; a throw of 1 or 2 selecting branch (g). They are more likely to hang on and may even be reinforced by troops originally destined for the defense of the town itself. Events are likely to proceed much as above, with the player still trying to break through. Success will lead on to Chatsk as before, but another defeat will be more serious, and could well result in an enemy attack in the player's sector. I have not extended these particular paths of alternatives further, since my aim is to illustrate the method, rather than provide details for a full solo campaign. It only remains to examine events at Chatsk, which I envisage as a reasonably large town with a few key strong points and two or three bridges over the Zandroi. It is in the player's interest to get here as soon as possible, since delay will allow more defenders time to arrive. The individual soloist would be the best judge of how many defending troops to use and still maintain a balanced scenario. Results are once again divided into four strategic outcomes:

-

11. The attackers clear the town on both banks of the river and seize the bridges intact.

12. The attackers clear the near side bank and prevent the enemy destroying the bridges, but are unable to obtain a secure bridgehead.

13. As (12) above, but the enemy destroy the bridges.

14. The attack on the town makes no headway.

These results can be developed further, and provide more battles in the same campaign. E.g., in case (11) the enemy might counter-attack before the player's force were able to consolidate their gains, leaving him with the choice of fighting on east of the river or falling back and defending the western bank. In this case High Command's wishes might not coincide with what the player (the commander on the spot) decides is tactically possible. Rules for what would happen in this case would also be required: one possible ending to the campaign is that the player finds himself relieved of command for failing to achieve the objectives set out in his orders!

This particular flowchart campaign has been written (in a very short time) with a particular objective but it is very easy to devise a larger one which covers more possibilities. I use three charts linked together. One of these is used when my own force is attacking. Another when the enemy are attacking, this being similar to the first except that I'm on the receiving end. The third chart is used when the 'front' is stationary, and includes such operations as reconnaissance in force, engineering operations, etc. objectives are selected from a list by dice throws or some other convenient method.

This particular flowchart campaign has been written (in a very short time) with a particular objective but it is very easy to devise a larger one which covers more possibilities. I use three charts linked together. One of these is used when my own force is attacking. Another when the enemy are attacking, this being similar to the first except that I'm on the receiving end. The third chart is used when the 'front' is stationary, and includes such operations as reconnaissance in force, engineering operations, etc. objectives are selected from a list by dice throws or some other convenient method.

The forces to be used need not be specified as long as some indication of relative strengths is given so that each player can adapt the campaign to whatever forces he has available. It would also be a simple matter to convert the campaign to a computer program, which would provide the orders and act as 'High Command', while the player attempted to carry them out on the table by more conventional methods. If anyone cares to try this sort of thing, they will find the initial work of developing the flowchart no more difficult than drawing the maps required for a 'conventional' campaign. Hopefully a further article will provide a few details on the sort of thing that you can use in the chart to build up your campaign.

Part Two of Mechanized Campaigns

Back to Table of Contents -- Lone Warrior #112

Back to Lone Warrior List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Solo Wargamers Association.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com