Preamble

As a first attempt at providing at material for Lone Warrior I chose something reasonably well documented, straightforward and of local interest. The only thing I was right about was that it was local! I make no claim to be a historian and have not accessed "primary sources" just standard textbooks and reference works available at most decent libraries. I freely take the blame for all inaccuracies and ridiculous interpretations. But if I can commit myself on paper then anyone can, so get on with it and contribute. Any comments are welcome either through LW or to me direct. If anyone is intending visiting the site please feel free to contact me.

Historical description and Background

In 1399 Henry Bolingbroke defied exile and returned to England to claim his father's estates. Landing at Ravenspur on the Humber he quickly gained support, most notably from the powerful families headed by Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, and Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland. The king, Richard II, hastily returned from campaigning in Ireland to find Bolingbroke had sufficient popular support to be declared King Henry IV and have Richard imprisoned.

Early the following year supporters of Richard attempted to kill the new king and restore Richard. Predictably Richard disappeared soon after. Bolingbroke's claim to the throne was tenuous but Richard had been unpopular and had no direct heir, the nearest candidate was the eight year old Earl of March, Edmund Mortimer. Overall then the country seemed content with the situation.

The first few years of Henry's reign were full of wars and rebellions. Although technically at peace with France this was the middle of the "Hundred Years War" and most years saw raids one way or the other across the channel. France also often provided support to both the Scots and Welsh in their campaigns against the English. On the Scottish border warfare was more or less continuous.

In 1402 Henry's old allies the Percys won a major victory against the Scots and French allies at Homildon Hill. Many Scottish nobles were killed or captured. Amongst the prisoners was a notable leader, the Earl of Douglas. The Scottish Earl George Dunbar fought with the Percys at this battle. He had turned to the English for support following a feud with the Douglas family in which the Scottish king had ruled in favour of Douglas.

Also in 1402 a battle took place at Pilleth in Wales. This had a far less satisfactory outcome for the English king. Owain Glyndwr had defeated an English force under Sir Edmund Mortimer (Sr), and captured Mortimer himself. This war in Wales had started as a local dispute between Glyndwr and an English neighbour but escalated until Glyndwr claimed the Principality of Wales.

In July 1403, the English king was heading north to join the Percys in a campaign against the Scots, who were seriously weakened as a result of the previous year's defeat. His son, also Henry, had a small army in Shrewsbury, Shropshire keeping a watch on Glyndwr and raiding in North Wales. Glyndwr himself was probably in Carmarthen following a minor defeat at the hands of an English force under Lord Carew.

Around the 12th of July the King's army marched into Nottingham to be greeted with the startling news that the Percys had risen in revolt.

Campaign

By the time the King received news of the revolt the head of the Percy family, Henry was in the North of England recruiting forces on his estates. His son, also Henry, nicknamed "Hotspur", was recruiting in Cheshire accompanied by his ex-prisoner, Earl Douglas. Cheshire was a centre of support for the deposed King Richard and many ex-members of Richard's bodyguard still lived in the area. The Percys adopted Richard's emblem of the hart and declared Richard was still alive and would join them at Chester. Hotspur soon had a sizeable force which contained many experienced warriors, both knights and archers, although Richard himself never did appear despite several further promises.

Several reasons were given for the revolt. These included that the king had not provided enough money to fund the Percy's defence of the northern border, that the Percys had only agreed to help Bolingbroke recover his estates not usurp the crown and that the king had failed to ransom Hotspurs brother-in-law Edmund Mortimer from Glyndwr. This last seems particularly unlikely as by this time Mortimer had married Glyndwr's daughter and now supported the Welshman. Underlying everything was probably the usual struggle for power and money. A major factor seems to have been the king's continuing support of the exiled Scottish Earl, George Dunbar. He had been a dangerous, skilful adversary for the Percys. With support from the English King he could well undermine the Percys pre-eminence in the North.

The king hurried west, reaching Burton on Trent on the 16th of July, where he heard more details. Hotspur's forces were moving on Shrewsbury to destroy Prince Henry's small army. This would open the way for them to join Glyndwr's army and then strike for the English heartland. Issuing orders to raise levies the king rushed on to Shrewsbury with his existing forces. He arrived at Shrewsbury only hours after Hotspur just before an assault could be made on the town. Hotspur fell back a few miles north of the town towards the village of Berwick on the 19th or 20th of July. A day or two of manoeuvring followed with the king attempting to prevent the rebels escaping north and uniting with additional forces raised by Henry Percy Senior. A number attempts at reconciliation failed and the two sides met in battle array around midday on "a bloody field by Shrewsbury".

A cast list is provided later to keep track of the various Henrys, Edmunds, etc.

The Battle

Details of the battle itself are obscure and fragmentary.

The Armies

Most sources agree that the king's forces were larger by 50% to 100% although one report says ten times larger. The actual numbers recorded vary from 5,000 to over 60,000 per side. Around 10,000 for Hotspur and 15,000 for the king is in line with most accounts and ties in with the reported casualties in the battle. An army of 15,000 deployed 16 deep in a continuous line would require a frontage of about half a mile at 1 yard per man. This is in line with the space available in the area of the battlefield.

The composition of the armies can only be guessed. Both sides had longbowmen. Those on the rebel side recruited from Cheshire and surrounding counties being reckoned better than average and probably including substantial numbers from Richard's old bodyguard. Hotspur was also reported as having a large following amongst the nobles, suggesting a higher proportion of knights, again many of whom were experienced warriors from Richard's personal retinue. It is possible Prince Henry's troops at Shrewsbury were the core of the royal army with many of the more experienced warriors and those with the king contained recently raised forces. Individually many would be experienced campaigners but not used to working together as an army.

In terms of leaders the Percys also had a distinct advantage. Both Hotspur himself and Earl Douglas had plenty of experience in commanding armies in the wars on the Scottish border. The third main rebel leader at the battle was Thomas Percy, Earl of Worcester had fought in France, Spain and at sea as Admiral of England.

On the royalist side the King was a seasoned warrior but did not have the same sort of command experience as the rebel leaders. Prince Henry later to achieve fame at Agincourt was not yet sixteen and the Earl of Stafford was probably a competent warrior but no military reputation. The best leader on the royalist side was the Earl George Dunbar who had the same background as Douglas and Hotspur and was likely well acquainted with them.

According to various chronicles the king's army was divided into two divisions commanded by the King himself and Prince Henry. Later though we hear that the vanguard was commanded by the Earl of Stafford. This could be taken as meaning that the army was divided into the traditional three battles: the vanguard under Stafford; the main battle under the King and Dunbar; and the rearguard under Prince Henry.

I prefer to suggest that Prince Henry kept control of his own army and the King's army formed two or three battles on its own. It is implied the rebel army formed three battles; under Worcester; Hotspur and Douglas. There is not enough information to give maps of deployments but I hope to give some suggestions in a later article on wargaming the battle.

The Battlefield

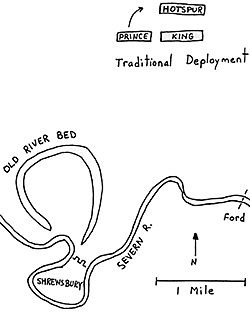

In 1403 Shrewsbury was virtually an island in a loop of the River Severn. The only land approach was from the north over a narrow neck of land which was guarded by the castle, town walls and probably a wet moat. Two bridges crossed the river into the town. The river even when low would be a major barrier to any army of the time. The land approach to the north was further restricted by an old river meander which even today has steep banks and a very marshy bottom. Other than this the land was mainly flat farmland dotted with settlements, woods and ponds. Two major routes headed north from the town over this terrain. This is shown on Map 1.

In 1403 Shrewsbury was virtually an island in a loop of the River Severn. The only land approach was from the north over a narrow neck of land which was guarded by the castle, town walls and probably a wet moat. Two bridges crossed the river into the town. The river even when low would be a major barrier to any army of the time. The land approach to the north was further restricted by an old river meander which even today has steep banks and a very marshy bottom. Other than this the land was mainly flat farmland dotted with settlements, woods and ponds. Two major routes headed north from the town over this terrain. This is shown on Map 1.

Modern accounts favour a battle site immediately to the north of Battlefield church, with the King facing north and Hotspur on rise facing south. I have been unable to find out why this particular location is so popular. It seems to derive from Victorian times based on various descriptions written a hundred years or more after the battle and somewhat doubtful interpretations of features seen on the ground. The only near contemporary accounts describes the battlefield as "level with a standing crop of peas which the rebels lashed together....". and as "within view of the Abbey at Haughmond.....". The suggested site has the King's army facing up a noticeable slope. The Abbey itself is visible some three miles but is not a notable feature. Presumably in 1403 it was much more conspicuous with a massive tower and possible a white limewashed exterior.

There are many other places nearby where the Abbey is equally or more visible so there are plenty of other possible sites. By offering battle at this spot Hotspur would have allowed the king space to deploy his superior numbers. I prefer to suggest Hotspur formed up further south preventing the king marching north from Shrewsbury and deploying his forces fully. The king countered by fording the river at Uffington on the night of the 20th leaving the prince to garrison Shrewsbury. This outflanked Hotspur's position and force him to redeploy facing South East somewhat south of the usual accepted battle site.

The course of the battle. The leading battles of the armies clashed, initially exchanging longbow fire. The royal troops, under Stafford, probably hampered by the terrain suffered badly. The archers fell back on their supporting men-at-arms closely followed by the rebels, led by Douglas. The whole wing of the royal army started to disintegrate and it is likely it was at this point that Stafford was killed. Hotspur and Douglas then led a charge, presumably mounted, on the king's position. They narrowly failed to reach the king, who on Dunbar's advice was not wearing his royal colours and had withdrawn from the danger area. They did kill the king's standard bearer, Sir Walter Blount, along with at least two decoys wearing royal arms.

Prince Henry's force had avoided much damage from the initial archery and turned the right flank of Hotspur's army. The prince was wounded in the face but pressed on. In the close quarter melee that ensued Hotspur was killed, possibly by an arrow in the face. As the news spread his army disintegrated and was pursued for a number of miles.

Casualties were high on both sides, a total of between 5,000 and 10,000 with perhaps 3,000 more wounded, many of whom died soon after. The names of 16 royalist and 8 rebel knights who died in the battle are known, and one account speaks of 200 knights and squires from Cheshire dying in the battle. The presence of longbows on both sides for the first time in a major battle doubtless contributed to these figures. A foretaste of the Wars of the Roses.

The Aftermath

Hotspur's body was initially buried, but later exhumed and displayed to stop rumours he was still alive. Following trials for treason Worcester and several other leading rebels were hung, drawn, and quartered and their heads displayed. Other rebels forfeited estates or were pardoned. Douglas, as a Scot, could not be tried for treason and was kept in custody for ransom or as a hostage. Henry Percy Senior submitted to the king and was pardoned, only to revolt again a few years later.

In 1408 a chapel and college was established on the battlefield to give thanks for the victory and pray for souls of those who had died. This was instigated and paid for by local landowner Richard Husse who seems to have fought at the battle. It was approved and various rights and benefits confirmed by royal charter. The college ended in 1548 but the chapel later became a parish church until declared redundant in 1982.

The Battlefield Today

The church is clearly marked on modern maps just north of the junction of the A49 and A53 in the area still known as Battlefield. The OS grid reference is SJ 512173. The church contains several displays about the battle, some decorations showing the heraldic devices of the loyalist knights who fought and a model of the battle. The church is usually locked although I believe keys can be obtained from a nearby house. In recent years it has been open on Sunday afternoons through the summer. The area immediately around the church is still open farmland. The usual story has the king's headquarters immediately south of the church with Hotspur deployed up the slope north of the church. Further south in the area I prefer as the battlefield the land is now covered by supermarkets, houses and industrial estates. Shrewsbury itself is still dominated by the Severn, causing bad traffic problems. The castle still stands and is now a military museum.

References

The main books I have used are easily accessible:

Oxford History of England "The Fifteenth Century" by E.F.Jacob.

Ordnance Survey "Complete Guide to Battlefield of Britain" by D.Smurthwaite.

"Walking and Exploring the Battlefields of Britain" by John Kinross

"The Battle of Shrewsbury 1403" by E.J.Priestley . This pamphlet is produced by the local council and not widely available. Numerous articles in journals and newspapers in the local studies collection of Shropshire libraries.

Notes: Cast List

Royalists

- * Henry IV (Bolingbroke): King of England

* Prince Henry: King's son and future Henry V.

* Humphrey, Earl of Stafford: Commander of royal vanguard.

* George, Earl of Dunbar: Scottish exile and enemy of Douglas.

Rebels

- Sir Henry Percy (Sr): Earl of Northumberland, father of Hostpur.

* Sir Thomas Percy: Earl of Worcester, brother of Henry Percy (Sr).

* Sir Henry Percy (Jr): Known as Hotspur.

* Earl of Douglas: Scottish noble formerly a captive of the Percys.

Owain Glyndwr: Welsh noble leading fight against English king.

Sir Edmund Mortimer (Sr): Hotspur's brother-in-law, Glyndwr's son-in-law, uncle and guardian to Edmund

Sir Edmund Mortimer (Jnr): Earl of March, heir to Richard II, a minor in 1403.

Note - Those marked * fought at Shrewsbury.

Back to Table of Contents -- Lone Warrior #106

Back to Lone Warrior List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Solo Wargamers Association.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com