The German-born commander of 6th Army, Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger, was

sixty-three years old and near the pinnacle of his career. His remarkable military life

began as an enlisted man in the Spanish-American War, and he would cap his career in

1944 with a fourth star.

The German-born commander of 6th Army, Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger, was

sixty-three years old and near the pinnacle of his career. His remarkable military life

began as an enlisted man in the Spanish-American War, and he would cap his career in

1944 with a fourth star.

At the 32d Division command post at Aitape. From left to right: Maj. Gen. C. P. Hall, commanding general of task forces; Maj. Gen. William R. Gill, commanding general of 32d Division; and Maj. Gen. Leonard F. Wing, commanding officer of 43d Division.

In his memoirs, General Krueger wrote that increasing Japanese

activity in June and the capture of enemy documents revealed that the enemy planned an

intensive reconnaissance of the Aitape area.

[46]

Krueger could not then write about the role of Ultra in forewarning his

command of Japanese intentions. SWPA's Central Bureau indeed provided a running

intelligence commentary on the activities of General Adachi's 18th Army. Much of this

Ultra information, in turn, appeared in sanitized form in SWPA's Daily Intelligence

Summary, which was much more widely available to field units. Concealing the source

of the precise information on Japanese activities, usually with the caveat "According to a

Japanese PW," enabled SWPA G-2 to pass enormous amounts of Ultra-detected

intelligence to its lower echelon units. The very volume of available intelligence

information perhaps tended to confuse rather than to enlighten the intelligence analysts.

Without the complete Special Intelligence Bulletin (SIB) issued by SWPA, it is

impossible to reconstruct with exactitude the Central Bureau's analytical process. The

results of those labors, however, also appear in the Daily Intelligence Summary and,

coupled with the Ultra information in the Magic Summary-Japanese Army Supplement, do show the unfolding intelligence estimate of 18th Army's situation. This tactical appreciation reveals Ultra in a far different light from its heralded strategic value. The Ultra-derived perception of the enemy came to rule the conduct of operations as a weapon whose tactical benefit was, at best, enigmatic.

Only two days after the Aitape landing, SWPA intelligence analysts first

surfaced the idea that the Japanese would probably bypass Aitape in order to attack Hollandia. Exactly where this interpretation originated is unknown, but it colored General Krueger's perception of the Aitape covering force's role until late June and, perhaps, even later. Krueger feared that Persecution Task Force might be contained within the main line of resistance (MLR)

while the Japanese bypassed it and attacked Hollandia. During the next few weeks, for

example, SWPA G-2's Daily Intelligence Summary reported that although a Japanese

attack on Aitape was within enemy capabilities, it was not considered probable because

the enemy "gains nothing." Allied troops at Hollandia would still be athwart 18th Army's

supply lines (30 April-1 May 1944).

A few days later, G-2 reversed itself and suggested that an attack on Aitape would achieve more than one against Hollandia (3-4 May 1944), but shortly thereafter, it analyzed such an attack as diversionary in nature to allow the main body of 18th Army to slip around the south flank of the Aitape defenses (8-9 May 1944). The mid-May Japanese attack against Company C, 127th Infantry, at Babiang was initially believed to be the expected Japanese counterattack, and analysts thought that Japanese maneuver units would try to reach Aitape as quickly as possible (16-17 May 1944). Because the Japanese, however, did not follow up their attack, G-2 in late May again advised that all indications pointed to a Japanese attempt to bypass Aitape (25-26 May 1944). [47]

When Ultra illuminated 18th Army's exact battle plans, overreliance on the Ultra sources blinded analysts to subtle shifts and variations in the Japanese scheme of maneuver.

The first Ultra-derived indication of Japanese intentions to attack Aitape appeared from the decryption of a 28 May message from Southern Army to Tokyo. Available to SWPA on 1 June, the message was a plea to rush supplies to Wewak by the end of June "due to the attack on Aitape by Mo [18th Army].

[48]

This information, plus additional SWPA intelligence garnered from two letters written by Japanese officers of the 239th Infantry Regiment stating that their division would join the 20th Division in an attack against Aitape and Hollandia, appeared in the 2 June MSJAS. [49]

The following day the more widely distributed Daily Intelligence Summary

mentioned the possibility of a Japanese attack against the Aitape perimeter. [50]

Around this time Ultra eavesdropped on the Japanese staff deliberations

concerning operations against Aitape, and as the Japanese hammered out a consensus, Ultra provided SWPA all the Japanese options. It thus became more and more difficult to reconcile seemingly contradictory messages. A 7 May order, for instance, instructed 18th Army to use "aggressive tactics" during its withdrawal, but to attempt no "suicidal"

moves. Other messages showed 18th Army hardly prepared for offensive operations,

existing on reduced rations with only half the ammunition required for a major

engagement.

Beyond Ultra, SWPA depended upon the cumulative intelligence evidence,

human intelligence (HUMINT), aerial reconnaissance, POW interrogations, captured documents, and patrol reports to piece together their mosaic of Japanese intentions. Amidst this welter of conflicting, incomplete, and sometimes contradictory evidence, it is not surprising that G-2, SWPA, clung to its original assessment that although the Japanese might be able to complete their attack preparations by the end of June, the attack would only be a cover for further withdrawals, with no "desperate" moves planned. [51] In short, they attributed their own rationality to their Japanese opponents.

Although the week of 11-18 June provided only minor contacts between roving Japanese and American patrols, on 17 June General MacArthur offered General Krueger the use of a regiment of the 31st Infantry Division to meet the impending Japanese threat near Aitape. Krueger, who by that time was planning his own "vigorous counteroffensive" against 18th Army, informed MacArthur that he preferred the veteran 112th Cavalry Regiment to a green unit from the 31st Division. Krueger's conviction that veteran troops could fight and kill the enemy better, faster, and with fewer friendly casualties was almost universally accepted among Army officers. Postwar studies, based

admittedly on limited comparative data, lend support to this popular notion. [52]

MacArthur agreed with Krueger's recommendation and, on 24 June, ordered the 112th Cavalry RCT* to Aitape.

Although earlier Krueger had been reluctant to request reinforcements, that same day a 155mm howitzer battalion was sent to Aitape to replace artillery sent to new operational areas in western New Guinea. Number 71 Wing, Royal Australian Air Force, simultaneously received orders to remain at Aitape. Krueger also reversed himself and ordered the 124th Infantry Regiment, 31st Infantry Division, to Aitape and a speedup in shipping the 43d Infantry Division from its New Zealand staging area to Aitape. [53]

These reinforcements would bring U.S. forces near Aitape to more than two divisions, leading Krueger to form a corps-level headquarters. He selected Maj. Gen. Charles P. Hall to command this newly created XI Corps. Born in Mississippi in 1886 and graduated from West Point in 1911, Hall was a highly decorated World War I veteran and had spent nine of the interwar years at the Infantry School. Hall and his staff, however, had only recently arrived in New Guinea fresh from the United States and, according to General Gill, "didn't know anything about jungle fighting," being "untrained in this thing from the top down." [54]

Krueger's instructions to Hall were:

Recent information indicates that the Japanese are planning an all-out attack against our forces in the Aitape area. It is estimated that the enemy can concentrate in the area south and east of Yakamul, by 30 June, a combat force of 20,000. Additional units of a strength of approximately 11,000 are reported to be in the Wewak area.

Missions assigned to the Persecution Task Force remain unchanged (defense of the Tadji Drome and other installations at Aitape). In carrying out these missions you will conduct an active defense, breaking the initial impetus of the Japanese attack against a flexible defense system and following up with a vigorous counteroffensive when the strength of your force and the tactical situation permits [sic]. [55]

Persecution Task Force had evolved rapidly during May and June as additional reinforcements and support troops poured into the Aitape area.*

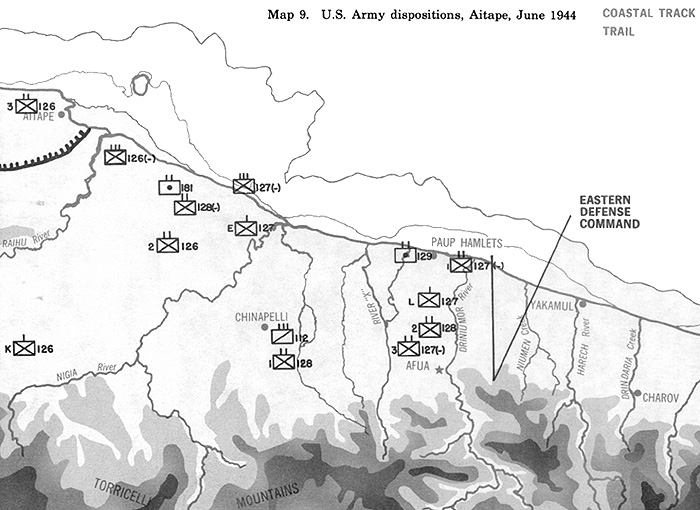

Major General Gill, now placed in command of Eastern Defense Area, realized that any serious Japanese threat would develop on his eastern flank, and he therefore devoted his energies to strengthening that line. On 10 June, Gill's West Sector was held by the 126th Infantry Regiment (minus its 2d Battalion); his Center Sector was held by the 128th Infantry (minus its 1st Battalion); and the East Sector, by the 127th Infantry

and the two battalions taken from West and Center, respectively.

This reinforced covering force was commanded by Brig. Gen. Clarence A.

Martin and designated Eastern Defense Command. Its defensive line was anchored on Driniumor's west bank, about thirty-five kilometers from the Tadji airfields (see map 9). This distance, most of it through jungle terrain, and the increased manpower required that logistic priority be given to the covering force.

Resupply reached the units along the Driniumor through a variety of means. Small boats moved supplies along the coast, and native-portered ration trains carried provisions along the coastal track. Materiel destined for Afua moved south inland from the coast along the Anamo-Afua trail or, later during the campaign, over an inland track running from the Tadji airfields through Chinapelli and Palauru. After the Japanese ambush of a ration party in early June, the command resorted to air drops for resupply. A dropping ground about 2,000 meters north of Afua served as the main resupply point for U.S. units operating near Afua.

Units defending the Driniumor used radio to communicate with each other, but telephone to talk with higher headquarters. Radio range, however, was limited by the thick jungle vegetation, its impenetrable canopy, and atmospheric conditions. Most radio communications at night simply deteriorated into static. Telephone contact depended on easily broken wire. Friendly troops walking over it, artillery exploding on it, humidity rotting it, or, worst of all, Japanese patrols cutting it made wire communications as undependable as radio. Still, jungle trails and defensive perimeters were soon crisscrossed with telephone wires, because as the official historian notes, it was usually less hazardous to string new wire than to attempt to splice breaks in the line, particularly when the Japanese laid ambushes at those places where they had cut the wire. [56]

Artillery and air support at Aitape were also augmented as the Japanese threat loomed ever closer. After the original three P-40 squadrons of No. 78 Wing, Royal Australian Air Force, departed at the end of May, only the 110th Reconnaissance Squadron of the U.S. 5th Air Force remained. Then on 9 June, No. 71 Wing, RAAF, equipped with Beaufighters, arrived at Aitape and provided close air support throughout the campaign.

The 5th Air Force A-20s and B-25s provided additional air support, staging first from Nadzab and later from Hollandia. Fifth Air Force C-47s, also flying from those two bases and occasionally from the Tadji strips, flew the aerial resupply missions that dropped rations and ammunition to U.S. troops along the Driniumor.

[57]

The 181st Field Artillery Battalion's 155-mm howitzers reinforced the organic 105-mm. howitzers of the 32d Division and provided artillery support. [58]

Artillerymen worked under severe handicaps at Aitape because photomaps were too inaccurate to provide them a basis for a firing chart to enable them to plot accurately the locations of friendly troops. Air observation and numerous fire registrations partially alleviated, but never solved, the problem. To compensate for their deficiency in accuracy, artillerymen resorted to quantity. An Army historian described the "tremendous expenditure" of artillery ammunition, estimated by XI Corps to be the largest expenditure in any campaign up to that time in SWPA. [59]

As will be seen, their profligacy would also require an enormous logistical effort just to keep the guns supplied with ammunition. In the defensive perimeter around Aitape, artillerymen positioned their batteries in diamond-shaped formations to obtain all-around fire. They located their batteries near the beach line to get minimum range necessary. All howitzers were dug in, and positions contained protective cover for

ammunition and crews. [60] These guns would be decisive in disrupting one Japanese attack after another.

With reinforcements either in place or on the way, Krueger, though confident he could meet any contingency, believed that "the expected attack could not be met successfully by Aitape Task Force standing on the defensive." [61]

Here, it seems, Ultra dictated his operational directives.*

On 25 June the first translations of the "complete plan of attack by the 20th and 41st divisions became available." [62] Central Bureau had intercepted and decrypted a Japanese signal that announced that the attack against Aitape "is scheduled to begin about 10 July and to be made by approximately 20,000 troops, according to an 18th Army (HQ Wewak) message dated 20 Jun[e]." It should be noted that the signal made no mention of a Ranking attack against Afua. Central Bureau apparently derived that perception from the analysis of Ultra together with captured letters, written by Japanese officers of the 239th Infantry Regiment in

mid-May, documents captured on 31 May, and the reported disposition of the Japanese 78th Regiment. Nonetheless, the 27 June MSJAS paraphrasing SWPA's special intelligence reports described the plan outlined in the 20 June intercept as calling for the 20th Division to attack west across the Driniumor, while the 41st moved south and attacked north and northwest toward the Aitape and Tadji airfields. Accompanying this information was a hand-drawn map illustrating the 20th Division's frontal attack across

the Driniumor about three kilometers from the mouth of the river, concurrent with the 41st Division's envelopment of the southern U.S. flank, thence north towards Aitape.

Such a plan of attack reflected Central Bureau's translators' and analysts' interpretation of the 20 June message.* [63]

According to the original Japanese attack order, the final assault against Aitape would indeed originate from the south, but it would not involve a flanking maneuver. After both Japanese divisions broke thrugh the center of the American covering force, the Japanese planned to envelop these American defenders from the rear, destroy them, and then regroup to attack Aitape from a southwest axis.

The very next day, SWPA reported that according to another intercepted

message the Japanese intended to make a preliminary attack across the Driniumor on 29 June. This 24 June signal emanated from Headquarters, 20th Division, whose commander, Lt. Gen. Nakai Matsutaro, wanted his troops to drive back the American covering force "as early as possible" to facilitate the second, and main, Japanese attack against the American main line of resistance near Aitape.

Nakai communicated his plans for such a 29 June attack to 18th Army. But

because units of the 41st Division were unable to deploy properly by that date, he postponed the attack until 3 July and later was ordered to wait until 10 July. [64]

The SIB for 27-28 June reported this development along with the facts that Japanese units were far understrength, suffering severe supply difficulties, and cut off from possible reinforcement. Furthermore, additional fragmentary intercepts revealed that the Japanese had expressed doubts about their ability to accomplish this mission on time. The cumulative evidence led SWPA G-2 analysts to conclude that "supply

difficulties may force the date of the attack to be slightly delayed."

[65]

The 24 June intercept, however, probably did prompt General Krueger to fly from Hollandia to Aitape on 27 June to confer with his new corps commander, General Hall. [66]

Also present at the 28 June meeting was General Gill, now commanding the

Eastern Defense Area. Gill voiced his concern over his force being overextended and thus unsupportable because of the difficulties in moving artillery and supplies through the jungle from Aitape to the Driniumor. Cognizant of the possibility of an imminent Japanese attack on the covering force, he requested reinforcements and permission to withdraw his force into the main defensive perimeter. Krueger not only rejected Gill's proposal, but also ordered General Hall to strengthen the Driniumor covering force and

to take steps necessary to meet the Japanese attack with a powerful counterattack. [67] Because Ultra

had indicated the possibility of a Japanese attack the next day, 29 June, perhaps Krueger meant that Hall should be ready to counterattack when the opportunity arose. Hall's G-2 revealed XI Corps's concern about the reliability of 6th Army's intelligence when he questioned the source of Krueger's detailed information about the impending Japanese attack.

In reply, Krueger sent a top secret signal to XI Corps G-2 that explained that the Japanese scheme of maneuver and the objectives of the 29 June Japanese attack were "based upon further interpretation of ultra information." [68]

After 29 June had passed without a major Japanese attack, intelligence analysts reassessed their work and concluded that while the order of battle information in the 24 June message was accurate, the date of the attack had been postponed, exactly as they had foreseen. The 10 July date mentioned in the earlier 20 June intercept now appeared to be the day that the attack would commence. Further complicating the situation, on 30

June General Hall sent a priority message to General Krueger stating that a Japanese prisoner captured near Yakamul had reported an "attack to be made between first and tenth July" against U.S. lines along the Driniumor.

[69]

The Daily Intelligence Summary for 1-2 July, again resorting to the cover of a POW report, provided extensive details of the Japanese tactical order of battle for the impending attack, including the two-pronged plan of maneuver. The interpretation of a Japanese frontal assault to fix U.S. defenders, while the main force units maneuvered south around the covering force's flank, had taken on a life of its own.

[70]

Its origins may be found in the original SWPA assessments that 18th Army

would try to bypass Aitape to the south. In short, overwhelming evidence indicating a Japanese attack was available, but the framework of analysis remained flawed.

As the Japanese maneuver battalions worked their way into their attack

positions, their headquarters elements followed closely, negating the need for wireless communications between command echelons and reducing the number of Allied intercepts. In addition, atmospheric conditions and numerous breaks in Japanese landlines forced the Japanese to forsake both wire and signal communications and resort to runners to insure the delivery of critical orders. These factors influenced both the Japanese and American conduct of the battle, as a brief background of the situation demonstrates. On 30 June General Adachi and 18th Army Headquarters staff arrived at Charov, where a subsequent conference among Adachi and his division commanders eventually ratified his plan to conduct a frontal attack in deep echelon on a narrow front. No flanking maneuver was planned. After the initial breakthrough and destruction of the U.S. covering force, the Japanese would reorganize and press on toward Aitape. These verbal orders to division commanders naturally were unavailable to SWPA analysts who continued to think in terms of a two-pronged attack.

Even more significant, runners hand-carried Adachi's final attack order, issued 3 July, to the respective division commanders resulting in two inadvertent consequences. First, it delayed significantly the receipt by Japanese units of their operational orders. In the case of the 41st Division, for instance, orders did not arrive until the morning of 7

July and forced the division to deploy and attack over ground that it had no time to reconnoiter. [71] Second, with Ultra dried up, Central Bureau never did intercept the definitive Japanese plan of attack against Aitape.*

American patrols took up the Ultra slack and reported increased enemy activity. [72] Moreover, on 7 July so-called secret information, most likely distilled from the reevaluation of available intercepts and captured documents, reached the covering force. This information indicated that the Japanese planned to attack the Driniumor line on 10 July. [73] With four infantry battalions and one cavalry regiment deployed on or in reserve along the Driniumor, the covering force, alerted and prepared for an attack, seemed in perfect position to wreak havoc on any Japanese assault. In fact, however, the Japanese achieved tactical surprise, broke through the U.S.

lines, and precipitated a bloody month-long fight for control of the Driniumor. General Krueger's own tactical decisions facilitated the Japanese breakthrough.

Krueger chafed at standing on the defensive. He perceived from Ultra that the Japanese intended to attack the Driniumor covering force, and he understood the pitiful supply situation plaguing the Japanese maneuver units. Furthermore, Ultra assessments led him to expect a two-pronged Japanese attack that would develop as a holding action to cover a Japanese envelopment of the covering force from the south. Simultaneously,

Krueger's 6th Army was conducting major operations at Hollandia, Wakde, Biak, and Noemfoor and preparing for the Sansapor invasion. Krueger was under enormous pressure, and rather than let the Aitape situation linger, he decided that "it was desirable to develop the situation and bring matters to a head. Accordingly he ordered a reconnaissance in force to proceed to the Harech River and be prepared for further operations on Task Force order." [74]

The reconnaissance in force, ordered on 8 July, would proceed west along the northern and southern flanks of the covering forces. The northern force would disrupt any Japanese attempts to use the coastal road to transport supplies to their attack staging areas. The southern force would disrupt Japanese enveloping forces by forcing them into action before they were completely ready. The reconnaissance, however, required Krueger to strip away all reserves from the covering force, denuding, in Gill's words, "the pitiful force we had on the defense." [75]

The operation began on the morning of 10 July. That night thousands of Japanese would storm the U.S. lines. American patrols had been reporting increased Japanese pressure. But it had been strangely quiet in the Company F, 2d Battalion, 128th Infantry, sector, where only one patrol contact was reported between 29 June and 10 July. The absence of Japanese activity convinced the members of Company F that they were the target of an impending Japanese counterattack. They reasoned that the Japanese avoidance of the entire 2d Battalion sector suggested that the Japanese

intended to attack there. [76]

Japanese troops were active, however, in the 3d Battalion, 127th Infantry, sector, which bordered the 2d Battalion on the south. During the morning of 10 July, 3d Battalion patrols sighted several strong Japanese fighting patrols, but whether or not they reported these sightings back to Persecution Task Force commander remains uncertain.

Even if they had, the reports probably would have made little difference.

At Task Force Headquarters, General Hall was not unduly concerned about an imminent Japanese attack. He had been expecting a Japanese attack since 5 July and had no reason to believe that the night of 10-11 July would pass any differently from those preceding it. General Gill felt that his G-2 had not impressed Hall sufficiently, and consequently his warnings of an imminent attack were disregarded. For instance, Hall would not believe the Japanese could bring mountain artillery through the jungle nor would he give total credence to intelligence estimates developed by the 32d Division G-2 section. [77]

Hall signaled Krueger about 2330 that the reconnaissance in force eastward would continue the following day. [78] Maj. Gen. Charles A. Willoughby, SWPA G-2, was even more certain that the Japanese attack had again been postponed.

On 10 July the MSJAS reported that 18th Army's attack "which was scheduled to begin on that day had not been attempted and that there were no signs of the patrol activity which would be expected to precede the attack. G-2 SWPA suggested that the attack might have been postponed until urgently needed supplies could be received by submarine and plane and supplies in the forward area built up." [79]

The Ultra card, it seems, had been misplayed.

*The 112th's official designation was the 112th Regimental Combat Team (RCT). For the Aitape campaign, however, its 148th Field Artillery Battalion did not accompany the rest of the unit. So although identified as an RCT, the 112th at Aitape was in fact a dismounted horse cavalry regiment.

*See app. 2 for organizational charts depicting evolution of Persecution Task Force.

Members of 128th Infantry Regiment, 32d Division, move up to the front along the beach at Aitape.

Members of 128th Infantry Regiment, 32d Division, move up to the front along the beach at Aitape.

*See app. 1 for a sampling of pertinent Ultra-related intelligence assessments.

*The possible reasons for the interpretation are numerous: first, the ambiguity of the Japanese language; second, missing groups or "words" in the message; third, Ultra in combination with other intelligence sources altered perceptions; fourth, and not least, the intelligence analysts worked under tremendous pressure translating more than 20,000 intercepts in 1944 and did not have the leisurely retrospective powers time confers on historians.

*SRH-059, 026, argues that the 10 July attack followed the same pattern as the abortive 29 June plan. Although the plans were similar, the change of dates caused analysts difficulties in ferreting out Japanese intentions.

Back to Table of Contents -- Leavenworth Papers # 9

Back to Leavenworth Papers List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com