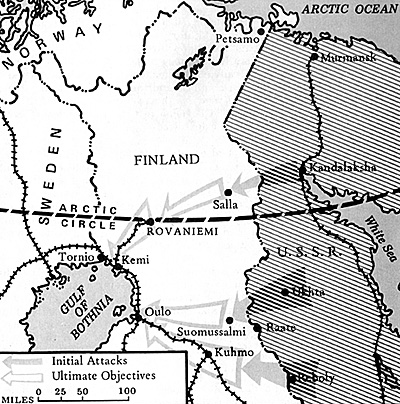

On 30 November 1939 the Red Army invaded Finland without a declaration of war and achieved tactical surprise at numerous points along the 900-mile common border.

Debris of the 44th Division along the Raate road.

Despite their overwhelming odds in men and firepower and their virtual monopoly of armor, Soviet forces suffered severe and humiliating reverses during the first several weeks of that 105-day conflict. A partial explanation is that about a third of Finland is north of the Arctic Circle, where one of the coldest winters on record had already begun. The Finns were prepared for combat in snow at subzero temperatures; the invaders were not. It was almost that simple.

Not all Red Army commanders, however, were indifferent to environmental factors or ignorant of Finnish capabilities. An eighty-seven-page pamphlet, Finlandiya i ee Armiya [Finland and its army], published by the Soviet Commissariat of Defense in 1937, noted that all Finnish troops were experienced skiers trained for winter warfare, and that their field exercises emphasized Finland's many natural defenses: rivers, swamps, thousands of lakes, and vast forests.

The future marshal of the Soviet Union, Kirill Meretskov, then commander of the Leningrad

Military District, which was initially responsible for the entire Soviet operation, cautioned

on the eve of the invasion that serious resistance could be expected. Comdr. Boris

Shaposhnikov, Chief of the General Staff of the Red Army, also anticipated a lengthy

struggle against stubborn defenders.

The future marshal of the Soviet Union, Kirill Meretskov, then commander of the Leningrad

Military District, which was initially responsible for the entire Soviet operation, cautioned

on the eve of the invasion that serious resistance could be expected. Comdr. Boris

Shaposhnikov, Chief of the General Staff of the Red Army, also anticipated a lengthy

struggle against stubborn defenders.

On the mistaken assumption that Finnish workers would welcome the Red Army as liberators, Stalin ignored his military advisers and rushed into the invasion without adequate preparation. In 1939--as in June of 1941--the Soviet military services paid an enormous price for Stalin's political miscalculations.

The most dramatic illustration of the price the Finns extracted was their annihilation of the 44th Motorized Rifle Division in January 1940. That battle is a classic example of what well-trained and appropriately equipped troops can accomplish against an enemy who has superiority in numbers and firepower but is not prepared for the special conditions of a subarctic environment. Such a region typically has dense coniferous forests, few and widely separated roads, and a very cold climate-not a favorable setting for the deployment of standard motorized or armored units in winter. It is a realm where specially trained and equipped light infantry may prove its worth.

Among the four Soviet armies initially involved in the invasion, the Ninth Army was to bisect Finland at its narrow waist by driving for the northern end of the Gulf of Bothnia. On 30 November the Ninth Army commander hurled three divisions across the border, but they could not cooperate with one another because they were separated by sixty to one hundred miles of roadless woods. Thus it is possible to examine the central prong of the Ninth Army's offensive in isolation from other operations.

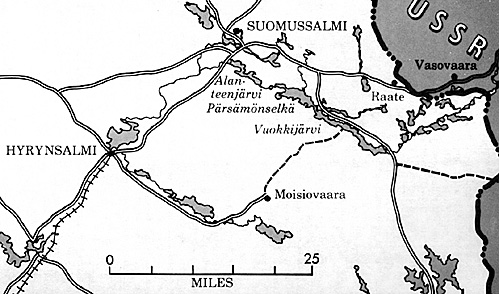

The main units of the 163d Rifle Division brushed aside a fifty-man covering detachment on the minor road that ran from the border near Juntusranta to Suomussalmi village, while the division's reconnaissance battalion and one rifle regiment pushed back two Finnish infantry battalions along the better road to Suomussalmi from Raate, about thirty miles south of Juntusranta. On 7 December the two columns joined forces to capture Suomussalmi, some twenty-five miles from the Soviet border. There a brigade of less than 5,000 men held the 163d Division in check until more reinforcements could reach that remote district.

By Christmas the Finnish forces totaled 11,500 men, reorganized as the 9th Division. This division had been formed in haste from various reserve units that happened to be available; only one of its three infantry regiments, JR*27 (JR="Infantry Regiment") , commanded by Lt. Col. Johan Makiniemi, had been a part of that division before the war (the other peacetime regiments had previously been deployed to distant regions). Lt. Col. Karl Mandelin's newly formed JR65 was rushed to Suomussalmi from Oulu. Lt. Col. Frans Fagerna"s's JR64 arrived from the southwest and included the only regular army troops in the division. These reserve units had never before served together, but coordination was good because all of the regimental commanders and the division commander, Col. Hjalmar Siilasvuo, were veterans of the 27th Jaeger Battalion. That unit of some 1,800 Finnish volunteers had fought in the Kaiser's army against the Russians in the First World War. After Finland gained its independence from Russia in December 1917, those Jaeger veterans received additional battle experience in the Finnish civil war of 1918. They also became the nucleus of the Finnish officer corps.

On 27 December Colonel Siilasvuo launched a major counterattack against his opponent, who outnumbered him by several thousand men and also enjoyed a vast superiority in firepower. In two days of fierce fighting the Finns shattered the 163d Division; before the month ended its survivors were fleeing in disorder northeast towards the frontier. By then the snow was at least three feet deep and the mercury dipped to -30' to -40 degrees. Daylight lasted only about five hours.

While the battle with the 163d Division was still developing, the Ninth Army had dispatched along the Raate road a strong reinforcement, Commander Vinogradov's elite 44th Motorized Rifle Division. This regular army unit was originally from the Kiev Military District, and most of its troops were Ukrainians who were not familiar with northern woods. (In contrast, many of Siilasvuo's men were lumberjacks in peacetime.) The crew of the Finns' lone airplane* spotted advance elements of the 44th Motorized Infantry Division as early as 13 December, and they estimated that the main components were on the Raate road by the twenty-fourth.

- *Colonel Siilasvuo had but one obsolete plane at his disposal. Although it could be flown only at

dawn or dusk, it was effective for reconnaissance because the Russians were clearly visible on the roads.

The Soviets employed very few aircraft here, although the Finns saw many bombers overhead enroute to

Oulu and other rear areas. Because of short days and the cover provided by the dense forests, air power

played a very minor role in the early campaigns in central Finland in general. The Soviets then directed their

bombing efforts mainly against Finnish towns and the defenses on the Karelian Isthmus far to the

south.

Had they succeeded in linking up with the 163d Division in time, the defense of central Finland would have been seriously jeopardized.

However, Colonel Siilasvuo had countered this potential threat before it became a reality. On 11 December he established a roadblock at a ridge between Lakes Kuivasiarvi and Kuomasjarvi, about six miles southeast of Suomussalmi. There Capt. Simo Makinen's two infantry companies, reinforced by additional mortars and guns, held up the advance of the entire 44th Division. Their success was due both to their own initiative and mobility and to the fact that the road-bound Russians were vulnerably ignorant about the strength and dispositions of the Finns.

The 44th Division had large amounts of motorized equipment, including about fifty tanks, all of which were confined to a single narrow dirt road through a pine forest. Under those circumstances the division could not bring more than a fraction of its abundant firepower to bear on the Finns at the roadblock. Although they had several hundred pairs of skis, none of the Russians had been trained to use them; therefore, even the infantry was confined to a radius of a few hundred yards on either side of the roadway.

In contrast, all of the Finns were experienced skiers and thus able to keep the 44th Division under constant surveillance. They also harassed it night and day with hit- and-run attacks on both of its vulnerable flanks, which stretched nearly twenty miles from the roadblock to the border. Approaching silently on skis and camouflaged in their white snowsuits, the Finnish raiders often achieved complete surprise. When they opened fire from the woods at close range, their Suomi submachine guns (firing seventy rounds per magazine) were especially effective.*

- *Each Finnish division was authorized 250 of these weapons, ideal for forest fighting which is

necessarily at close range. The Russian forces in Finland had nothing similar until February 1940.

Misled by the frequency and effectiveness of those attacks, Commander Vinogradov believed that a much larger force opposed him. Consequently, he made no major effort to rescue the 163d Division while it was being destroyed just six to eight miles beyond the roadblock. The minor attacks he launched on 24 and 25 December failed to dislodge Captain Makinen's small force. On the twenty-seventh, Vinogradov scheduled a new attempt to smash the roadblock for 1030 the next morning, but raids by two Finnish companies early on 28 December led him to revoke that order and to direct his division to dig in for defense on the road.

While still preoccupied with the numerically superior 163d Division, Siilasvuo had the foresight to order the preparation of an improvised winter road for future operations against the 44th Division. A truck equipped with a snow plow was driven over a series of frozen lakes that paralleled the Raate road about four to six miles to the south to form the winter road. The Finns also began clearing a snow trail about fifteen miles long from Moisiovaara, at the end of an existing road, to the winter road (the socalled ice road). This road system enabled them to supply their forces on the enemy's southern flank from a railhead twenty miles beyond Moisiovaara.

The Finns plowed another improvised road along the Haukipera watercourse to a point just west of Lake Kuivasjarvi. From there the road went overland (out of sight of the Russians across that lake near the roadblock), skirted the lake on the south, and then turned east. Where these winter roads branched cross-country from watercourses, the Finns used their usual method of compacting snow in areas where truck plows were impractical: a skier led a horse through the snow (in deep snow the horse proceeded by a series of jumps, which necessitated the rotation of lead animals), followed by a horse pulling an empty sled, followed in turn by a series of horsedrawn sleds with progressively heavier loads.

Previous Finnish experience in bitter fighting just north of Lake Ladoga had indicated that three miles was the extreme limit for effective flanking attacks in wooded wilderness. More ambitious attempts had failed because of the problems of communications, supply, and artillery control in such a heavily forested environment. Thanks to Siilasvuo's winter roads, however, which alleviated those problems, large- scale flanking attacks were successful fifteen miles beyond the roadblock.

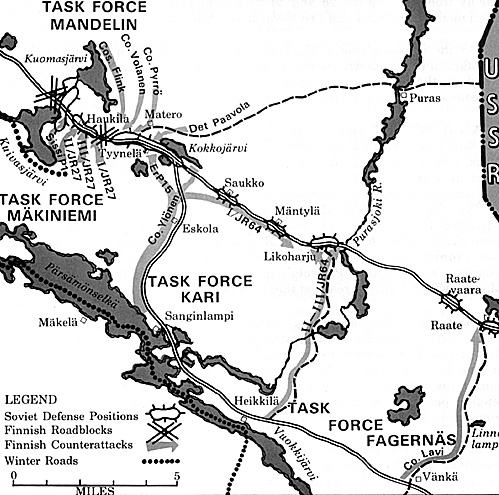

The initial moves to destroy the 44th Division began while mopping-up

operations against the 163d were still in progress. On New Year's Eve a reinforced

battalion of light infantry made a probing attack to the vicinity of the Haukila farm (see

map 6). Skirting Lake Kuivasjarvi on the south, they encountered a Russian battalion

east of the lake. They confirmed that the area was heavily defended. In fact, the largest

concentration of the 44th Division--a reinforced regiment and most of the division's

tanks and artillery-was strongly entrenched in a two-mile sector just east of the

roadblock.

The initial moves to destroy the 44th Division began while mopping-up

operations against the 163d were still in progress. On New Year's Eve a reinforced

battalion of light infantry made a probing attack to the vicinity of the Haukila farm (see

map 6). Skirting Lake Kuivasjarvi on the south, they encountered a Russian battalion

east of the lake. They confirmed that the area was heavily defended. In fact, the largest

concentration of the 44th Division--a reinforced regiment and most of the division's

tanks and artillery-was strongly entrenched in a two-mile sector just east of the

roadblock.

On 1 January a small reconnaissance unit reported that the enemy had occupied the Eskola area, about one and a half miles south of the Raate road on another road branching off from it and crossing the border to the southeast. To deny the Russians further use of that road, Siilasvuo immediately dispatched Capt. Ahti Paavola's light battalion to the Sanginlampi area, about three miles south of Eskola.

Now the winter road over the frozen lakes began to prove its worth. Paavola's troops easily skied along it for fifteen miles on New Year's Day, camping for the night near the Makela" farmhouse. Two larger strike groups, Task Forces Kari and Fagern'a's, also skied along that ice road during the first two days of January. They deployed from Suomussalmi to positions as far as twenty miles to the southeast from which they would later launch coordinated flank attacks. Maj. Kaarle Kari's three battalions bivouacked in the Makelh area, while most of Lieutenant Colonel Fagernas' two battalions camped near Heikkila. One reinforced company went as far as Vanka, just south of Raate.

All of those units enjoyed the comfort of Finnish Army tents, each of which was easily transported on one skifflike sled called an akhio, which was harnessed to three skiers, with a fourth behind it to steady the load. The units also used that simple carrier to haul mortars, heavy machine guns, and supplies and to evacuate the wounded. Each tent, heated by a wood-burning stove, kept twenty men comfortably warm on even the coldest nights. Lying on soft pine branches and sleeping in their uniforms, the Finns did not need blankets.

In marked contrast, the Russians huddled around open campfires or dug holes in the snow for shelter. At best, they had an improvised lean-to, a shallow hole covered with branches, or a branch hut fashioned at the roadside or in a ditch. The fortunate ones had a fire in a half barrel. Many literally froze to death in their sleep. Lack of proper footgear aggravated their misery; the summer leather boots which most wore contributed to many frostbite cases. Finnish estimates put Russian losses from the cold as high as their battle casualties. Once the Finns had begun major and sustained counterattacks, the enemy's problems of survival worsened: it became too dangerous to use open fires at night.

Numbering about a thousand men, Capt. Eino Lassila's battalion (1/JR27) began the first sustained effort to cut up the 44th Division during the night of 1 January. Using the winter road previously cleared around the southern end of Lake Kuivasja"rvi and extending to the east, a rifle company moved ahead as a trail security party during the afternoon of 1 January. The remainder of the battalion followed about an hour later. By 1700 the entire battalion had reached the end of the horse trail (the winter road), where they ate a hot meal before proceeding to their objective some three miles to the north. Pulling machine guns and ammunition along on akhios, they traversed those last miles through dark woods in deep snow and bitter cold silently on skis.

About 2300 the advance guard reached a ridge about four hundred yards from the Raate road, where they could see the enemy grouped around numerous campfires. Captain Lassila positioned six heavy machine guns on each side of the assault force on the ridge. He ordered two rifle companies to advance abreast and very close to one another, while the third remained in reserve near the command post behind the ridge. Upon reaching the road, one company would push east, the other west, to seize about five hundred yards of the roadway. Then the attached engineer platoon would throw up roadblocks in both directions by felling trees and mining them.

A half hour after midnight the assault companies advanced, overran the sentries posted about sixty yards from the roadway, and reached the road with little opposition. By a fortunate accident they had emerged from the woods some five hundred yards east of their assigned objective, the Haukila farm. Instead of the strong infantry defenses they had expected, the Finns fell upon an artillery battalion, which they easily captured. When they struck the road all of the field guns were facing west; although the Russians managed to turn two pieces towards the south, their crews were shot down before they could fire a single round. The Soviet four-barreled antiaircraft machine guns were also ineffective because they were mounted so high on trucks that they fired over the Finns' heads. The Finnish assault companies completed their task in about two hours with only light casualties; they did not even need the reserve company.

Using the horse and sled method described above, the battalion supply troops worked all night long to extend the winter road from the end of the horse trail to the battle area. About 0700 the first priority shipment arrived via this route-two antitank guns. They saw action almost immediately when the Russians launched their first counterattack from the east. Within fifteen minutes they destroyed seven tanks on or near the road, making the roadblock even more effective. The Finns also beat off an infantry attack.

Later that morning hot meals were sent forward from the support area, and tents were erected behind the ridge. The troops then rotated so they could warm up and have hot tea inside those shelters. Except when under immediate attack, they were routinely relieved after two hours of exposure to the cold. In contrast, the Russians were both cold and hungry. Finnish patrols deliberately sought out field kitchens as targets and eventually destroyed or captured all fifty-five of them. Each day the roadblock held, the Russians grew weaker and more demoralized.*

- *The Finnish term for such an entrapped enemy force is a motti, which is their word for a stack of

firewood piled up to be chopped. Motti warfare became a common feature of the battles in the forested wilds

north of Lake Ladoga. When the Finns lacked sufficient firepower to reduce strong mottis--some of which

contained scores of tanks--they relied upon cold and hunger to destroy their enemies.

During the afternoon of 2 January about two companies of Russian infantry waddled through deep snow to hit Lassila's roadblock from the west, but the Finnish reserve company caught them from the flank and forced them to withdraw. Then, as later, the 44th Division failed to coordinate its counterattacks and thus permitted the Finns to deal with them one at a time.

That same day Capt. Aarne Airimos's battalion (III/JR27) assaulted the road on Lassila's left flank and encountered the strong defenses near the Haukila farm. Although he secured positions close to the roadway, he could not sever it. That evening Colonel Siilasvuo ordered Capt. Sulo Hakkinen to position his light battalion (Sissi P1**) closer to Haukila, where it could support the 1st and 3d Battalions of the 27th Infantry Regiment. Hakkinen also sent reconnaissance patrols east of Lassila's roadblock.

- **Sissi literally means guerrilla, but it should not be equated to partisans; it was essentially light

infantry employed in a manner similar to the U.S. Army Rangers, but Sissi units did not receive special

training like the Rangers. P: Battalion

Further to the southeast, on 2 January, Captain Paavola's light battalion advanced towards the Sanginlampi farmstead from Makela. Because the Russians had deployed considerable forces there via the road past Eskola, Siilasvuo had to send Major Kari's units to assist Paavola.

On 3 January Kari sent the 4th Replacement Battalion into the attack, and the next day it captured the Sanginlampi area in heavy fighting. Meanwhile, on 3 January one company of Sissi P1 cut the road north of Eskola, which enabled another of Kari's battalions (ER*** P15) to take Eskola from the south the next morning.

- ***ER:

Indedpendent (Detached)

Kari's third battalion (I/JR64) also reached Eskola that day. Thus, by 4 January Task Force Kari had secured an excellent attack position within two miles of the Kokkojarvi road fork.

At the same time Task Force Fagernas's battalions (11 and III/JR64) had been improving communications from the base camps towards the Raate road, but not close enough to alert the enemy. The company at Vanka constructed a winter road as far as Linnalampi, while the main units at Heikkila" opened a poor road part way to Honkajarvi. By 4 January both forces had relatively easy access to points within four miles of the Raate road.

On 4 January Colonel Siilasvuo issued orders for a general attack designed to destroy the 44th Division the next day. Two new task forces were assembled; Lieutenant Colonel Makiniemi's included all three battalions of his own regiment (JR27) plus the 1st Sissi Battalion (Sissi PI). Siilasvuo allocated six of his eight field guns to Makiniemi, because he had to attack the strongest known enemy concentration--in the Haukila area.

Lieutenant Colonel Mandelin's Task Force, two battalions of JR65 and three separate

units of company size or smaller, was to strike Haukila from the north in coordination

with Makiniemi's blow from the south.

Lieutenant Colonel Mandelin's Task Force, two battalions of JR65 and three separate

units of company size or smaller, was to strike Haukila from the north in coordination

with Makiniemi's blow from the south.

Just east of Makiniemi's sector, Task Force Kari-with three battalions and the remaining two field guns-was to destroy the strong units in the Kokkojarvi-Tyynela" region by flank attacks. With part of his force he was also to push east to link up with Task Force Fagernas. Comprising two battalions of JR64, Task Force Fagernas was supposed to cut the road about a mile from the border and at the Purasjoki River to prevent the 44th Division from receiving reinforcements from the east.

On the fifth, Soviet resistance was still so strong that none of those attacks succeeded completely. The Soviets checked three of Task Force Makiniemi's battalions as they closed on the Raate road east of the original roadblock. The fourth, Captain Lassila's battalion, which had been holding its stretch of the road since 2 January, lost ninety-six men that day as the Russians desperately attempted to break through to the east.

Attacking from the north, Task Force Mandelin also made little progress, although it did secure--too lightly, as it later developed--a minor road leading northeast to the border near Puras in order to block any Russian retreat in that direction. Task Force Kari's attacks in the Kokkojarvi and Tyynela areas were likewise thrown back on the fifth; the Finns sustained heavy losses at Kokkojarvi.

Task Force Fagernas achieved the day's best results, although it accomplished only half of its mission, its attacks in the Raate area and at Likoharju having been repelled. Near Mantyla, however, one of its platoons did ambush and destroy several truckloads of reinforcements that were part of the 3d NKVD* Regiment.

- *NKVD: People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs, which included both secret police and

border guard formations.

This had been sent to assist the 44th Division at the beginning of January. In a renewed assault that night, Fagernas finally took a stretch of the Raate road just north of Likoharju and held it against a strong counterattack from the east. Around 2200, his engineers blew up the Purasjoki River bridge, thus preventing further enemy truck traffic beyond that point (the river banks were too steep for motor vehicles).

The decisive battles occurred on 6 January. Task Force Makiniemi overcame stubborn resistance to widen its hold on the Raate road east of the original roadblock. By evening all four of its battalions had reached the road, and the 3d Battalion had established a roadblock west of the one the 1st Battalion was still defending against repeated attacks. About 0200 the next day the Finns resumed the offensive, and after an hour's battle the enemy troops facing the 2d and 3d Battalions (JR27) abandoned their heavy equipment on the road and fled towards Haukila hill.

On the opposite side of the road, Task Force Mandelin spent most of 6 January hunting down enemy stragglers who were retreating through the woods to the northeast. Trudging through the snow on foot, the demoralized Russians were easy prey for the Finnish skiers.

About 0300 on 6 January, a reinforced company of Task Force Kari cut the Raate road about a mile east of Kokkojarvi and established another roadblock, which it held against two strong counterattacks. Desperately trying to fight its way out to the east, the 44th Division was being cut into smaller and smaller fragments. Battalion ERP15 seized a segment of the road east of Tyynela about 1100, after a three-hour battle. The main forces of the battalion then turned west towards Tyynela. By afternoon the Russians were abandoning this sector and fleeing along the Puras road, where only two Finnish companies were screening a broad sector. Colonel Siilasvuo therefore sent Captain Paavola's detachment to block that escape route at Matero, which Paavola reached that evening.

The freshest Russian troops, including the NKVD unit, counterattacked Task Force Fagernas in such strength during the morning of 6 January that it had to withdraw a short distance into the woods to escape the fire of five Russian tanks. After their reserve company arrived, the Finns resumed the offensive near the Purasjoki bridge, where they established defensive positions west of the river. Nevertheless, Russian counterattacks continued near Likoharju late into the evening.

To relieve the pressure on Fagernals, Siilasvuo ordered Kari to send a battalion (I/JR64) against the enemy who were operating between those two task forces. That understrength battalion advanced along a forest path from Eskola to Saukko. Overcoming stiff resistance there, it pushed on by evening to Mantyla, which it took after several hours of fighting. By then so many Russian stragglers had bypassed the roadblock east of Kokkojarvi through the woods that they threatened the battalion's rear. Therefore, late in the evening the battalion commander turned his front from east to west and destroyed those harassing groups. The company near Raate also resumed its attacks on 6 January to prevent Russian movement on the road near the border.

Late in the evening of the sixth, Commander Vinogradov belatedly authorized the retreat that had been underway in many sectors for hours. He advised his subordinate commanders that the situation was desperate and that those who could escape should.

Although only mopping-up was necessary in most sectors on 7 January, the Russians were still trying to fight their way through to the east near Likoharju. About 0400, with the help of tanks, they threw a Finnish company back from the Purasjoki River. However, a Finnish counterattack at 1030 that morning dispersed the Russians in disorder. The Finns then continued westward to capture Likoharju, where they took many prisoners and five tanks.

The final attempt to rescue the 44th Division came during the early morning darkness when infantry, supported by artillery positioned behind the border, assaulted the company at Raate. After repelling that attack, the Finns sent a reconnaissance patrol two miles inside Soviet territory, where it encountered only support elements.

There was also minor fighting near Lake KokkojArvi and Tyynela early on 7 January, but the Russians knew they were doomed. At daylight, troops of Task Force Makiniemi crossed the Raate road near Haukila and pushed north until they linked up with Task Force Mandelin.

The Russians in bunkers along the shore of Lake Kuivasjarvi resisted stubbornly, but the Finns cleared that area during the day and opened the road to Suomussalmi. The last organized resistance came from bunkers near Lake Kuomasjarvi. A Finnish platoon dispatched late in the evening returned from those positions at 0400 on the eighth with seventy prisoners.

Mopping-up continued for several days, as the Finns hunted down halffrozen stragglers in the woods along the entire length of the Raate road and to the north. By the standards of that small war, the booty was enormous: the Finns captured 43 tanks, 70 field guns, 278 trucks, cars, and tractors, some 300 machine guns, 6,000 rifles, 1,170 live horses, and modern communication equipment which was especially prized. The enemy dead could not even be counted because of the snow drifts that covered the fallen and the wounded who had frozen to death.

A conservative Finnish estimate put the combined Russian losses (the 163d and 44th Divisions, plus the 3d NKVD Regiment) at 22,500 men. Counting killed, wounded, and missing, Finnish losses were approximately 2,700 (only about 12 percent of these casualties were frostbite cases).

Additional features of winter combat demonstrated in this classic battle include:

- The great utility of skis: The relative immobility of troops not trained to use skis affected intelligence as well as deployment. Finnish ski patrols kept their road-bound enemy under continuous surveillance, whereas the Russians remained ignorant of the Finnish strength and dispositions.

- The effectiveness of improvised roads: In terrain where trucks fitted with snowplows could not get through, the simple method of compacting snow with a series of horse-drawn sleds was quite effective.

- The advantages of specialized training and equipment: Sleeping on pine boughs in heated tents kept the Finns comfortable while their opponents were literally freezing to death a few hundred yards away.

- Unusual targeting: The Finns accelerated their enemy's debilitation by firing on his campfires and destroying his field kitchens.

The Russians had reason to regret the folly of launching their invasion without thorough preparations to cope with the environment, but they were not the last to make that costly mistake.

Back to Table of Contents -- Leavenworth Papers # 5

Back to Leavenworth Papers List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com