It is now over two hundred and twenty years since the

American Revolution began and arguments still rage over its

origins. There is always the popular arguments that are based

on the ideas that revolution was fuelled by the desire to shake

off the chains of foreign rule by a tyrannical monarch. On

the other side there arguments put forward by some

academics that the revolutionaries were self interested

hypocrites mouthing clichés about democracy and freedom

to the masses in an effort to protect their own individual property rights. 1

Whatever the reasons, popular or otherwise, the period between the skirmish at Lexington and

the siege of York was one of revolutionary change in the

history of warfare. Revolutionary because it is not only one

the first examples of global warfare but also because it is a

war fought between a major colonial power and colonists of

European decent. It is also revolutionary as the first example

of a major revolutionary war where the ideal of “nation - in - arms’ plays a crucial role . 2

The year of 1775 saw civil disturbances in Britain’s American

colonies escalate into open warfare. The blame for this turn

of events is often laid at the feet of General Thomas Gage

who eagerly sought permission to suppress the activities of

American troublemakers with a show of military force.

However, when Gage finally received the orders he desired

he put them into effect so ineffectively that after defeats at

Concord, Lexington and Bunker Hill, he was replaced. For

both sides the Battle of Bunker Hill was, at best a tactical

draw but it signaled the end of the political phase of the

revolution and represents the beginning of a war for independence . 3

The standout decision of 1775 occurred at the Second

Continental Congress. The decision was to elect General

George Washington as Commander in Chief of the army.

Appointing Washington is seen as a surprise move

considering that until the time of his election his military

career had been continually frustrated. His involvement in

actions at Fort Duquesne and Braddock’s ill fated

Monongahela expedition, during the French and Indian War,

did not inspire thoughts of a great military career. Furthermore, his efforts to distinguish himself from the

regular crop of provincial officers of the Crown had also met with failure . 4

Nevertheless, what Washington did posses

was patience, perseverance and courage, attributes that made

him a great strategist and enabled him to keep his army

together when hardship and defeat threatened to destroy it.

Field Marshal Montgomery, of World War II fame, commented that Washington, matured as a leader

throughout the course of the war but was never more than a mediocre soldier . 5 This comment may seem harsh when considering Washington’s overall talents as a commander,

however if taken as a reflection of his tactical abilities in

combination with his lack of success on the battlefield, then

the comment is well-founded.

Although the American colonies declared their independence on the 4th July 1776, the British increased their

efforts to subdue the rebels. The war was not popular in

Britain, neither were there sufficient British troops to supply

the needs of commanders in America. To meet the military

needs of the generals the government in London introduced

troops hired from various German states after failing to

secure the support of Catherine the Great of Russia . Quite

incorrectly these troops are often referred to as mercenaries,

incorrectly because they were never hired on an individual

basis, but were regular army troops in the employment of

their home states.

Their introduction did give British commander, Sir William Howe, the extra muscle he required.

Howe, initially gained victories at Long Island, White Plains,

Fort Washington and Fort Lee. Even though Howe

achieved these victories he is generally considered to be a

cautious commander and it has been determined that the

task he faced, of imposing a plan of united and coordinated

action, in north America was never going to be achieved. 6

When the nature of the geography of the American continent and continued political interference from London are also taken into account then the reasoning is certainly strong.

During this period Washington used his extraordinary

powers of perseverance and patience to great effect, just to

keep his army together. His patience was rewarded and

American morale boosted when at Trenton he crossed the

Delaware and surprised then defeated the German force

stationed there. A further boost to American morale came

with another victory in early January 1777, this time against

the British at Princeton. Shocked by these twin defeats Howe

ordered that his outposts be drawn closer to New York. This

decision left Washington and his army free in New Jersey,

therefore saving the army from disintegration.

Howe’s next step was to attempt the capture of Philadelphia.

Washington made an attempt to stop him along the line of

Brandywine Creek, he failed, mainly due to poor

reconnaissance work and Cornwallis’ flank march. Howe’s

force eventually marched into the American provisional

capital. The battle at Germantown was Washington’s attempt

to dislodge the British from Philadelphia through a surprise

attack, this failed also, leaving the British to settle down in

their comfortable winter quarters while Washington and his

army went into less comfortable quarters at Valley Forge.

Meanwhile in the north General John Burgoyne with a mixed

force of British, German, Loyalist and Native Americans

advanced southward from Canada. The aim of the campaign

was to link up with Howe and his army advancing along the

Hudson River to Albany. The effect of such a union would

have meant the closure of the Hudson River to the

Americans and created a physical split between the rebellious

northern colonies and the colonies of the south, which the

British believed to be loyal.

As seen, Howe had other ideas and Burgoyne was left on his own. Trying to apportion blame for the failure of the British army in the Saratoga

campaign is not important, out numbered and with no

chance of resupply Burgoyne had little choice but to

surrender. The importance of the defeat was that it

convinced the French to openly join the war against Britain.

What had been a struggle to maintain control over their

thirteen colonies in America had, for the British, developed

into global conflict that by 1780 also included Spain and the

Netherlands.

1778

Militarily 1778 was a quieter year, Washington remained in

command of the American army and Sir Henry Clinton had

succeeded Howe who had resigned as commander of the

British and their allies. Clinton was unique amoung the

senior British commanders of the war. Born in

Newfoundland he was the only one with a natural connection with North America. 7 The year however, marked

significant changes in the direction of the war. Firstly, the

battle at Monmouth virtually ended the war in the northern

theatre with the seat of the war moving south, a region

which the British saw as a Royalist stronghold.

Second, 1778 also saw the first active involvement of French forces. The

inauspicious start with the action at Newport resulted in

anti-French riots in many cities, the worst being in Boston.

Comte D’Estaing, the French commander, cannot be held

singularly responsible for the failure, his unwillingness to

commit his fleet in unfamiliar waters, without reliable charts

or local pilots and with the possibility of imminent storms is

an understandable response for a sailor.

1779

1779 saw American victories at Kettle Creek, Stony Point

and Paulus Hook. The year also saw increased French

involvement in the war. The siege of Savannah was another

chance for D’Estaing to prove to the Americans the value of

a Franco-American alliance. However, the siege ended in

failure with D’Estaing forced, by approaching storms at sea

to assault the town earlier than originally planed, the assault

failed and the siege called off. D’Estaing was again criticised

for his role in an operation, perhaps unjustly.

Historians, while being quick to criticise, fail to recognise that in the lead

up to the siege of Savannah D’Estaing and 1500 of his men

were stranded for six days with no shelter or supplies in

hostile territory. This feat is made remarkable by the fact that

they remained completely undetected. If British or Loyalist

units had detected this force the possibility of producing a

morale boosting victory over French regulars may have led to

the French re-thinking their involvement in the war.

1780

May of 1780 saw what is argued as the Americans greatest defeat of the war .8 General

Benjamin Lincoln surrendered the city of

Charleston, South Carolina, to the British.

Quite unfairly Lincoln is made a scapegoat

even though he is significantly outnumbered

and like Cornwallis at Yorktown he had no

chance of relief. The surrender gave Britain a

second major port city in the south. Alarmed

by British success in the south Washington sent

General Horatio Gates, the ‘victor’ of

Saratoga, to command the American southern

army against British general, Charles

Cornwallis.

Gates however, blundered to an

embarrassing defeat at Camden and was

replaced by General Nathaniel Greene. The

outlook for the Americans looked grim, the

outlook worsened when Benedict Arnold, the

disgruntled hero of Saratoga, went over to the

British cause, it was an act which, in the end,

achieved nothing. A victory over a British force

e being arguably the most talented and formidable of the

at Kings Mountain gave American morale a critical boost.

Problems for the British increased as Cornwallis, despite

being arguably the most talented and formidable of the

British field commanders, failed to understand the nature of

the southern topography nor the fighting qualities and

tactics of the patriots . 9

Now with Nathaniel Greene, the only American general to

serve with Washington for the entire war, in command of the

army in the south and with the exceptional Daniel Morgan

leading in the field the Americans won a crushing victory

over Banastre Tarleton at Cowpens. In the words of Morgan they gave Tarleton “a devil of a whipping”.

10 Cornwallis,

perhaps eager to redress the balance after Tarleton’s defeat

met Greene at Guilford Court House.

Greene adopted a defensive posture and Cornwallis, in line with his aggressive

nature, attacked. Although, the battle was a tactical victory for the British Cornwallis’s casualties were so great and his

cavalry arm so small that he was unable to make the victory decisive.

Greene’s command of the American army in the south

makes an interesting study. Although he failed to win a

victory in the field, his subordinate commanders, Morgan,

Henry Lee and Francis Marron utilised harassing tactics that

eventually forced the British into there strongholds of

Charleston and Savannah where they remained ineffective.

At this point it is interesting to note that the harassing tactics

employed by Greene and his subordinates were more in line

with the theories expounded by Charles Lee earlier in the

war. Lee’s theories centred on the use of local militia forces,

skirmishing and harassing the enemy to wear them down.

Washington had previously spurned Lee’s theories

preferring to adopt European style linear tactics using

regular troops.

There are significant differences between the

terrain over which Washington fought his battles and the

rivers and swamp systems of the south where Greene

commanded. This is put forward as the major reason for the

commanders adopting different tactical styles. Despite the

differences in style, it is also argued that Greene’s tactics

played a much greater role in forcing the surrender of

Cornwallis at Yorktown than the formal European tactical

doctrines used by Rochambeau and Washington during the siege . 11

Yorktown

Sir Henry Clinton, British Commander in Chief, suggested to the frustrated Cornwallis two options. First, advance by land and link up at New York, or second take up a defensive position on the coast to be transported by sea. Without clear orders from his superior Cornwallis retired, by land, to Yorktown, Virginia. Even as he retired with Lafayette’s American troops nipping at his heels, Cornwallis still had enough of his fighting spirit to ambush Lafayette's advancing columns at Jamestown Ford, only night saving the impetuous French aristocrat.

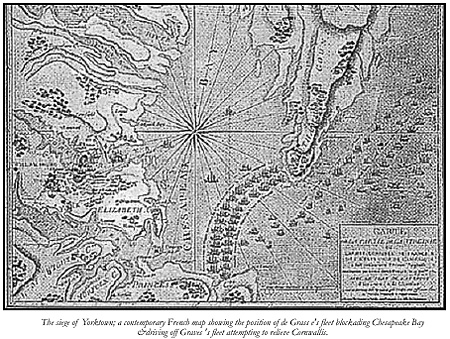

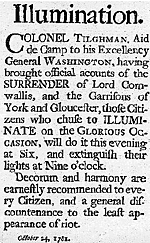

Finally arriving at Yorktown, Cornwallis survived three weeks of siege before surrendering. The surrender occurring only after the

Royal Navy had failed to break the French blockade and storms had prevented evacuation by small boat to Gloucester on the other side of

Chesapeake Bay. Such was the magnitude of the surrender at Yorktown that effective British military involvement in North America ceased.

Tactically the war did not introduce any new or radically different military theories. However, it reintroduced many of the theories of light infantry tactics that had been developed during the French and Indian Wars by officers such as Wolfe, Howe and Amherst. These tactical doctrine had fallen into disuse and the British army had re-‘Prussianised’ itself. It took a renewal of conflict in America for the British to

relearn the role of light infantry . Certainly the idea of the British fighting in a European style with the Americans fighting a guerrilla war is something of a fallacy. 12

Even though the Americans were more flexible in their approach, the armies commanded by Washington fought in a linear style that their British opponents would have been quite used to. The failure of the Americans in set piece battles gives weight to the argument that they could not compete with the high standards of training and discipline of the British regulars.

The case that the British evolved and developed tactics suitable to the north American battlefield has often been ignored, instead the failures of York, Bunker Hill and the Saratoga campaign are shown as typical examples of the British method of fighting. Campbell’s capture of Savannah, the attack on the American rear by Prevost at Briar Creek and the flank march by Cornwallis at Brandywine are evidence of the flexible and mobile capabilities that the British army possessed. 13

The great rivers, forests and lakes presented much greater difficulties to the British than the nature of the topography in Europe. 14 Particularly

when the armies were attempting to subdue a large continent while drawing their supplies from coastal ports. Guibert argues that this factor alone was the great equaliser in the conflict. 15 Many of the arguments presented, may appear to be pro-British, in some cases this is intentional since much of the

popular image of the war relates to American brilliance and British stupidity. Certainly, there are examples of both these extremes, Cowpens and Bunker Hill being two respective samples. However, applying this combination to the entire war gives an unbalanced and unhistorical viewpoint. More often than not British competence and American ineptness was the combination. In the end what remained was a new but distinctly unstable nation.

A nation that again fought the British in 1812 and turned in on itself with a Civil War in the 1860’s where the paths left bloody by the armies of Greene, Cornwallis and Washington were again bloodied by their descendants Lee, Longstreet, Grant and Meade.

1 Morgan, E. S. Revisionists in Need of Revising in Billias, G. A. (ed). The American Revolution; How Revolutionary Was It?, p40 - 41.

The siege of Yorktown; a contemporary French map showing the position of de Grass e's fleet blockading Chesapeake Bay & driving off Graves 's fleet attempting to relieve Cornwallis.

The siege of Yorktown; a contemporary French map showing the position of de Grass e's fleet blockading Chesapeake Bay & driving off Graves 's fleet attempting to relieve Cornwallis.

In essence the failure of the British to succeed in defeating the patriots, is in part based on the strategic rather than the tactical errors of commanding generals, political interference from London and the lack of cohesion and communication between commands. However historians argue that the main reason for British defeat lies in the nature of the country.

In essence the failure of the British to succeed in defeating the patriots, is in part based on the strategic rather than the tactical errors of commanding generals, political interference from London and the lack of cohesion and communication between commands. However historians argue that the main reason for British defeat lies in the nature of the country.

Footnotes

2 Black, J. European Warfare 1660-1815 , pp158 - 159.

3 Marsh, W. Bunker Hill, A Dear Bought Victory , p 12.

4 Keegan, J. Warpaths , p 167.

5 Montgomery, B. L. A History of Warfare , p 321.

6 Keegan, J & Wheatcroft, A. Who's Who in Militar y History , p 164.

7 Keegan, J & Wheatcroft, A op cit , p 74.

8 Commanger, H & Morris, R. The Spirit of Seventy Six , p 1073.

9 Alden, J. R. The South in the Revolution , p 247.

10 Morgan, D. in Alden, J. R. op cit , p 254.

11 Strachan, H. European Armies and the Conduct of War , p 29 - 30.

12 Ibid.

13 Black, J. A Military Revolution? , in Rogers, C. J. (ed). The Military Revolution Debate, p 109.

14 Quimby, J. Background to Napoleonic Warfare , p 264

15 Guibert in Quimby, J. op cit , p 265.

Back to Table of Contents -- Kriegspieler #9

To Kriegspieler List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by Kriegspieler Publications.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com