Horse and musket era and especially Napoleonic wargames rules tend to two main groups. There are the ‘high level’ rule sets, where, for infantry, a stand of (usually 3 or 4) figures represents roughly a battalion (say 400 to 600 men) and a group of stands represents a brigade or a division. The other main group is the ‘battalion level’, where a stand of figures represents roughly one or two companies and a group of stands represents a battalion.

In the ‘high level’ games representation of individual battalion formations tends not to be displayed except in very crude form and is taken account of by other mechanics or factors.

My interest is in representing unit level formations in ‘battalion level’ games. By unit I mean infantry battalions, cavalry regiments, artillery batteries (companies) and their equivalents.

Let’s take infantry first.

With the battalion level games, figure scale varies from 1:20 to 1:60, depending on rule set. 1:20, in which six figures represent a company of 120 men, gives a very good representation of battalion structure in terms of companies within a battalion. It also uses a large number of figures, and if using 25mm figures means only small battles of about brigade or small division a side can be fought on a normal size table. While company structure can be represented using a 1:50 or 1:60 figure scale, this results in two (at most three) figure companies and is less visually appealing. The commonly used WRG 1685-1845 rules with its rigid use of four figure elements combined with the 1:50 figure scale does not really permit proper representation of internal battalion structure.

Representation of company structure in terms of basing is important because the company was the key to the battalion level formation. On the battlefield, a column very rarely had less than a company frontage and the individual companies were the building blocks of the sides of a square.

All Napoleonic rule sets for battalion level games permit the three basic formations of line, column and square plus some version of skirmish lines. The more sophisticated also permit a representation of the French mixed order (Le ordre-mixed) and the Austrian battalion mass.

However, historically the choice of formation, depending on which nation’s regulations, was more subtle and varied than the basic list indicates.

Line

Lets take line to start with. Most people are aware of the British using a two rank deep line and most Continental armies using a three deep line.

The British also used a four deep line on occasion, especially when intending to oppose cavalry without going into square. Also, Continental armies would use a two deep line - especially light battalions and battalions where at least a proportion of the third rank was used for skirmishing (eg Austrians and Prussians). Late 17th Century armies using matchlocks would use even deeper lines.

Some rule sets cater for different line depths by having figure frontages for basing British infantry wider than that used for other infantry. Most make no distinction. Four deep line is also difficult to represent. Other aspects of lines not normally taken into account by rules are the tendency for troops in a tightly packed line to open out when engaged in prolonged firefights, in order to have more room to reload muskets, and for raw troops firing from the third rank to cause casualties on their comrades to their immediate front.

Column

Now lets consider column. Most rule sets only vary column types by the number of figures frontage.

The following table is taken from Nosworthy,("Battle Tactics of Napoleon & His Enemies" by Brent Nosworthy - reviewed in issue #6) and gives a description of different types of columns as seen on the battlefield.

Column A formation consisting of a series of platoons, companies or divisions (of a battalion) in lines placed one behind another at pre-determined distances (intervals).

Column at Full Interval A column where the distance separating each unit in the column equals the frontage of the first unit (also referred to as an ‘open order column’ or simply ‘open column’).

Column at Half Interval A column where the distance separating each unit in the column equals half the width of the first unit in the column (also referred to as a ‘half open column’).

Column at Quarter Interval A column where the distance between units is 1/4 of the frontage of the first unit in the column. (Closed column)

The following passage from Otto Von Pivka’s "Armies of the Napoleonic Era" is also of interest. "Movement on the battlefield was only rarely carried out in line due to the difficulty of controlling the manoeuvre; changes of position (apart from the charge) were carried out in column.

"Column could be formed on frontages of a file (three men), a platoon, company or (rarely) a battalion and was achieved in various ways."

Von Pivka goes on to discuss various ways of forming a column. So in addition to the types of columns mentioned in Nosworthy there was also the column with a frontage of 3 men, equivalent of a standard line where all soldiers turned 90 degrees to form a column. This sounds essentially similar to the “form fours” of the twentieth century British army.

The first main point for me is that the frontage of a column is not an arbitrary number of men (or figures) determined by current tactical operations, but is a fixed fraction of the major sub-formation within a battalion ie the company. The second main point is that there were different types of columns based on different front to back spacings between sub-units.

Further, a column was in essence made up of a series of sub-units in line.

Each of these columns had different tactical use and vulnerabilities.

The following passage from Nosworthy is interesting. “The French were the first to discover the utility of columns of waiting. Almost an inadvertent development, it came from the tendency of some French infantry commanders to maintain a part of their forces in column, slightly to the rear, even during the height of an engagement. … During this period there were many ways of describing a column. Columns were described by their width: a column of companies, a column of squadrons, a column of divisions and so on. Columns could also be described by their density; for example, a column at full interval (open column), a column at half interval (half open column), a column at quarter interval (closed column).

Occasionally, however, tacticians would classify a column according to the function it served. From this point of view, at the beginning of the linear period there had originally been three types of columns. Columns of route were employed to move large masses of infantry and cavalry across the countryside; columns of manouevre were used to move the troops around the battlefield; while columns of attack on rare occasions … were hurled directly at the enemy. A column of waiting was simply a column used to hold troops in reserve until the time they were needed for action.

… Sufficiently comforted that their infantry columns could now quickly deploy into line if required by circumstances, on a few occasions they experimented with leaving some of the infantry in the second or third lines in column until they were needed.

It was this new-found ability to remain in column closer to the enemy that would make possible another new formation, one destined for much notoriety: the mixed order.”

Leaving aside mixed order until later, I will now discuss the three types of battlefield columns outlined by Nosworthy. Column at full interval or open column was the standard battlefield column of manouevre for much of the Eighteenth century. This is the type of column that permitted easy formation of line to either flank by a 90 degree wheel of its sub-units. However, if the requirement was for a line facing the same direction as the original column then considerably more time was required from open column than was required from closed column. Open column formation could also move relatively quickly from one place to another. Its main weakness was its vulnerability to cavalry.

Column at half interval does not seem to have been used very much. The only reference to its use in Nosworthy is as a waiting formation in a recommended French corps deployment in the Austerlitz campaign. In actual practice closed columns were used.

Column at quarter interval - closed column - appears to have been the standard attack column. This also equates to the Austrian battalion mass - and was definitely not used solely by the Austrians. There is a picture of the Old Guard attacking at Montmirail (cover of Nosworthy) which is clearly a closed column. (Picture of Austrian column from Armies of the Danube for comparison.)

One of the great strengths of the closed column was how easy it was to convert to a square. The third rank of each company would run to the gaps and face outwards, almost instantaneously creating a solid square. Clearly the major disadvantage of the closed column was its vulnerability to artillery fire - even greater than that of the classic “hollow” square.

Closed column was also slower to manouevre than open column, however I can find no reference to its comparative speed with a line.

Battalion structure of major power armies c.1812:

| NATIONALITY | Number of Coys in Line Bttn. | Number of Coys front in standard attack column |

|---|---|---|

| French | 6 of 100-140 (paper 140) | 2 |

| Austrian | 6 of 160 (paper 218 ) | 1 |

| Prussian | 4 of 165 | 1 |

| Russian | 4 of 180 | 1 |

| British | 10 of 50-100 (paper 100) | ? |

French, Austrian and British units would often manouevre by divisions of two companies.

Square

As can be seen from the reference to forming square from closed column, there was even more than one type of square. The shape of a square would vary according to the number of companies in the unit forming it, but typically a square had four sides, with each face being made up of one or two companies in four ranks. This normal square was 'hollow', with a central area clear except for senior officers, unit colours and occaisional skirmishers from independent companies or artillerymen from nearby batteries who were taking shelter.

A third type of square was the rallying square. This was formed by skirmishers threatened by cavalry. "If skirmishers were unable to return to their supporting formations or to take advantage of unbroken terrain, they were to form a 'rallying square'. All the men within distance would run towards the officer or NCO who gave the order to rally. The first men to arrive would stand back to back and then successive groups would be made to face a different direction so that the square would grow layer by layer.

Rallying squares could be as small as the men from three or four files or up to eighty infantrymen. … Under no circumstances were the men to fire, for if they were caught denuded of fire, the enemy cavalry could rush in and attack with sabre or lance."

My reference calls rallying square a 'desperate expedient'.

Mixed-order and other composite formations Le ordre-mixed (mixed order) was reputedly a favourite formation of Napoleon's. Classically it was a line of battalions, with some formed in column and some formed in line.

"Small battalion-sized closed columns were positioned periodically along a single line. Typically, one or two columns were deployed in line between a column on each flank."

This formation was typically French. However, in his revised regulations of 1806 the Austrian Archduke Charles had a variant of this formation - single battalion, though.

![]() The Austrian version was a defensive formation. The six

company Austrian battalion was deployed with two

companies in line between columns of two companies.

The Austrian version was a defensive formation. The six

company Austrian battalion was deployed with two

companies in line between columns of two companies.

![]() The French would also form a mixed order with two

battalions- the centre companies from each battalion in two

distinct columns, with the grenadier (and possibly voltiguer)

companies in line between them.

The French would also form a mixed order with two

battalions- the centre companies from each battalion in two

distinct columns, with the grenadier (and possibly voltiguer)

companies in line between them.

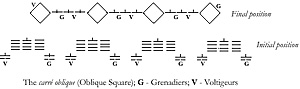

In the 1806 campaign against Prussia, the French also used a composite formation mixing line and square. There was a special feature of this formation in that the squares formed were 'oblique to the line of battle'.

The standard way of forming square was with a side facing towards the enemy. This meant that only the front side of the square could fire without endangering any friendly troops nearby. By rotating the square forty five degrees, and having a point towards the enemy, two sides could fire. The firing strength was reinforced by leaving the grenadier and voltiguer companies in line,linking neighbouring squares.

Skirmishlines

A single line of men drawn out in a skirmish line were very vulnerable to an aggressive charge by a formed unit, especially achargebycavalry.

It is difficult to find descriptions of how skirmish lines were drawn up. The following is an amalgam of several sources.

Skirmish lines were generally two deep, with a frontage of around one metre per man. Skirmishers operated in pairs, with one of a pair firing and reloading while the other 'covered'. Each company of skirmishers kept a small group of men a short distance behind the main skirmish line - these would form the nucleus of any rallying square or other quickly formed formation. Further back would be the main supports in line or column, either one or more companies of a skirmishing battalion or other formed units in the skirmisher's brigade.

Although standard practice by the end of the Napoleonic wars, Revolutionary French did not always have the supports for their skirmish lines - and were sometimes very badly damaged by sudden assaults by formed enemy, especiallycavalry. They learnt with experience.

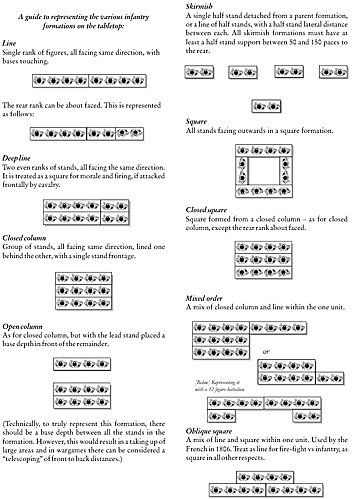

Representing Infantry Formations As indicated earlier, representing unit formations is a lot easier when using a basing system where one stand indicates a company. This type of basing is far easier when using a 1:20 or 1:30/33 figure scale. However, many of us have our figures based to the WRG 1:50 figure scale and four figure (regular foot) element.

The following are my suggestions for representing some formations using a 12-figure 3 WRG element battalion.

Some further thoughts on squares and columns

A squares greatest defence as the cavalry charge was the reserve of fire. This was making sure that each face of the square had at least one rank with loaded and undischarged muskets at all times. This was one reason for British squares being four ranks deep on each side. Steady infantry in line (or column) which were attacked frontally by cavalry could use the same tactics of fire as were used by a square. The battle of Minden in the Seven Years War is a classic example of infantry in line holding off frontal cavalry charges. However, note the two provisos - the infantry must be steady and the cavalry must attack frontally.

The two deep line when menaced by cavalry obviously finds it more difficult to keep the reserve of fire indicated in the previous paragraph. This is why British would form a four deepline on occasion.

With single battalion columns, it can be seen that these would be formed on at most a two company front, and that only by units with at least six companies. In wargames terms, this means that a column front should not be more than one third of the figures in a battalion.

A battalion deployed in the standard French column of divisions - two company frontage. Each company deployed in

three ranks each of about 90men (1809 establishment). [As depicted in David Chandler's "Atlas of Military Strategy"]

A battalion deployed in the standard French column of divisions - two company frontage. Each company deployed in

three ranks each of about 90men (1809 establishment). [As depicted in David Chandler's "Atlas of Military Strategy"]

Guide to Wargaming Infantry Formations

Back to Table of Contents -- Kriegspieler #9

To Kriegspieler List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by Kriegspieler Publications.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com