The War of the Third Coalition against France was going badly for the Austrians, after five days of heavy fighting the Austrian invasion of Bavaria (which precipitated the conflict) was over.

After the fall of Regensberg (or Ratisbon) the Austrians under Archduke Charles were in full retreat back into Bohemia after suffering nearly 45,000 casualties (as opposed to about 16,000 for the French and their allies). Napoleon had tackled the divided Austrian forces, defeating them in piecemeal fashion and Charles knew he must now concentrate his forces if he was to have any chance of defeating Napoleon. To do this he needed time; time to withdraw without his army suffering further mauling, time to concentrate available forces - calling in virtually every Austrian army throughout the Empire and, finally, time to prepare for tackling Napoleon’s army on the ground of his choosing.

To effect the latter Charles chose to assemble his army near the Marshfeld, the old Austrian Army training ground on the other side of the Danube just to the northwest of Vienna. To secure his safe withdrawal Charles constructed an effective cavalry screen to mask his movements north of the Danube and used a sizeable portion of his army, the VI and V Corps; approximately 40,000 men under FM Josef Hiller, to cover the left flank of the Austrian army and, by doing so conduct a ‘coat-trailing’ operation on the southern approaches to Vienna. In a masterful display of strategic thinking, by sacrificing Vienna Charles had bought himself time to recover and also managed to completely deceive Napoleon as to his true intentions which in turn eventually brought the Emperor closer to total defeat than he had ever come before at Aspern & Essling.

The Vienna ‘Freiwillinger’ (Volunteers) at Ebelsburg, 1809. This contemporary print is an exaggeration as although the Volunteers’ 4th & 6th battalions did throw back the French assault in their first action they did not actually reach the bridge over the Traun river. (After F. Wöber)

The Vienna ‘Freiwillinger’ (Volunteers) at Ebelsburg, 1809. This contemporary print is an exaggeration as although the Volunteers’ 4th & 6th battalions did throw back the French assault in their first action they did not actually reach the bridge over the Traun river. (After F. Wöber)

Charles’ strategy had Napoleon believing that he would encounter the Austrian main force before Vienna and thus he continued to pursue Hiller thinking that he represented the tail end of Charles’ army. Uncharacteristically, this time the superb French light cavalry could not penetrate the dense Austrian cavalry screen with any great success and failed to bring Napoleon any accurate intelligence on Archduke Charles’ movements - he remained unaware that the bulk of the Austrian army had already crossed the Danube.

Meanwhile Hiller kept just ahead of the rapidly advancing French (II & IV Corps) under the veteran Marshal Andre Massena. As instructed, he defended river crossings where possible and destroyed bridges, occasionally turning to fight skirmishing actions before resuming his withdrawal. Although in retreat the Austrians displayed their usual stoicism and were still able to turn on their pursuers and inflict a sharp reverse such as at Neumarkt on 24 April - they may have been beaten but were far from defeated. Although only a minor action in the 1809 Campaign, Ebelsburg gave a foretaste of what was to come at Aspern and Wagram. The Austrians could no longer be considered so easily beaten.

OPPOSING FORCES AT EBELSBEG

AUSTRIAN

V & VI CORPS: FML Johann HILLER

V Corps: Archduke Louis, FM Reus

Division FML Lindenau

- Brigade GM Mayer:

- IR#3 ‘Erzherzog Karl’ (3)

IR#50 ‘Stain’ (3)

6 pdr Brigade Battery (8 guns)

Brigade GM Berenburg:

- IR#2 ‘Hiller’ (3)

IR#33 ‘Sztarrai’ (3)

6 pdr Brigade Battery (8 guns)

6 pdr Position Battery (6 guns)

Division FML Reuss-Plauen

- Brigade GM Bianchi:

- IR#39 ‘Duke’ (3)

IR#60 ‘Gyulai’ (3),

6 pdr Brigade Battery (8 guns)

Brigade GM Rothacker:

- IR#58 ‘Beaulieu’ (3)

1 , 2 & 3 Bttns, Vienna Volunteers

6 pdr Position Battery (6 guns)

Division FML Schustekh

- Brigade GM Felso-Kubinyi:

- 7 Broder Grenz (2),

8 ‘Kienmayer’ Hussars (8),

3 pdr Grenz Brigade battery (8 guns)

Brigade Radetzky:

- 3 ‘Erzherzog Karl’ Uhlans (8)

8 Gradiskaner Grenz (2)

6 pdr Cavalry Battery (6 guns)

V Corps Reserve Artillery

- 2 x 12 pdr Position Batteries (12 guns)

1 x 6 pdr Cavalry Battery (6 guns)

5 Pioneer Division (2 companies)

VI Corps: FML Johann HILLER

Brigade GM Nordman

- 6 Warasdin-St. George Grenz (2),

3 pdr Grenz Brigade Battery (8guns)

7 ‘Liechtenstein’ Hussars (7),

6 ‘Rosenberg’ Chevaulegers (8),

6 pdr Cavalry Battery (6 guns)

Division FML Kottulinsky

- Brigade GM Hohenfeld:

- IR#14 ‘Klebek’ (3)

IR#59 ‘Jordis’ (3)

6 pdr Brigade Battery (8 guns)

Brigade GM Weissenwolff:

- IR#4 ‘Deutschmeister’ (3)

IR#49 ‘Kerpen’ (3)

6 pdr Brigade Battery (8 guns),

6 pdr Position Battery (6 guns)

Division FML Jellacic

- Brigade GM Hoffeneck:

- IR#31 ‘Benjowsky’ (3)

IR#51 ‘Spleny’ (3)

6 pdr Brigade Battery (8 guns)

Brigade Ettingshausen:

- IR#32 ‘Esterhazy’ (3)

IR#45 ‘de Vaux’ (3)

6 pdr Brigade Battery (8 guns),

6 pdr Position Battery (6 guns)

Division FML Vincent

- Brigade GM Provencheres:

- 4 , 5 and 6 Vienna Volunteers (3)

5 Warasdin-Kreuzer Grenz (2)

3 ‘O’Reilly’ Chevaulegers (8)

3 pdr Brigade Battery (8 guns),

6 pdr Cavalry Battery (6 guns)

VI Corps Reserve Artillery

- 3 x 12 pdr Positional Batteries (18 guns)

1 x 6 pdr Positional Battery (6 guns)

6 Pioneer Division (2 companies)

FRENCH

II & IV CORPS: Marshal Andre MASSENA

II Corps 2 Div. (GD Claparede)

- Brig. Coehorn: 17 , 21 , 26 , 28 Legere, Tiraileurs du Po, Tiraileurs Corse (all units 1 bttn. each)

Brig. Lesuire: 27 , 39 , 59 , 69 , 76 Ligne (all units 1 bttn. each)

Brig. Ficatier: 40 , 88 , 64 , 100 , 103 Ligne (all units 1 bttn. each)

IV Corps 1 Div. (GD Legrand)

- Brig. Ledru: 26 Legere (3 Bttns), 18 Ligne (3 Bttns)

Baden Brig. : 3 Infantry Regt. (2 Bttns), 1 Infantry Regt. (1 Bttn.)

IV Corps Cavalry (GD Marulaz)

- 3 (2 Sqdns), 14 (3 Sqdns), 19 (3 Sqdns), 23 Chasseurs-a-cheval (3 Sqdns),

Baden Light Dragoons (4 Sqdns),

Hesse Darmstadt Guard Chevau Legers (1 Sqdn.)

THE AUSTRIAN POSITION

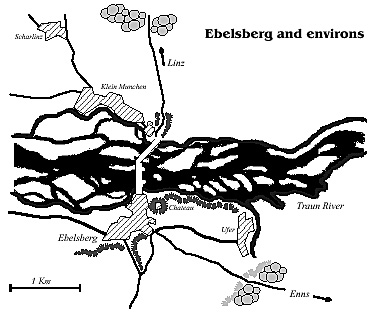

By the 3rd of May Hiller found himself at Ebelsberg on the Traun river, some 70 kilometers west of Linz. Here the position gave Hiller his best opportunity thus far for a successful rearguard action. Ebelsberg represented a natural defensive position situated in an amphitheatre of hills that formed a terrace around and behind the town. The Traun river at this point was deep and fast flowing; its waters swollen to a raging torrent by the spring melt of alpine snow. The only way over the river was via a 550 metre long narrow wooden bridge approached through a narrow defile. On the Ebelsberg side the approaches to the bridge were dominated by a formidable stone schlöss or castle situated on a small knoll next to the town (see map below). The road from Linz passed through some rugged heavily forested country and through a narrow defile just north of Scharlinz where the first of Hiller’s rearguard of a battalion of fusiliers was drawn up in line across it.

Different sources give Hiller anywhere between 22,000 and 40,000 men available at Ebelsberg. It seems most likely that, based on Austrian archives figures, Hiller had some 22,000 men and 70 guns in and around Ebelsberg with at least another 8,000 on the other side of the Traun. At least half of this latter figure represented part of Schustekh’s retreating division which was still crossing the Traun. The rest formed Hiller’s rearguard tasked with keeping the Linz-Ebelsberg road and approaches to the Traun bridge open as long as possible in order to delay the French and cover the withdrawal of the remainder of his force. A battalion of Grenzer sharpshooters were positioned in the houses lining the river and the schlöss garrisoned with three companies of the ‘Jordis’ IR59. In the cemetary and park adjacent to the castle were three battalions of raw militia, the newly raised 4 , 5 & 6 Vienna Volunteers, ranged in on the bridge below a 6 pounder battery and howitzer next to the schlöss tower. Forces on the other side of the river included a battalion each of the Gradiskaner Grenzer Regt. #8, ‘Spleny’ IR51 and ‘Benjowsky’ IR31 accompanied by uhlans and artillery.

Despite this considerable force Hiller suffered from several disadvantages; after several weeks of campaigning his men were tired with most units badly in need of rest and refitting. The speed of the French pursuit had kept the Austrians under considerable pressure; units tended to be scattered and overall command was frequently disjointed and uncoordinated.

This lead to considerable confusion on the western side of the Traun with some units advancing as part of the covering force at the same time other units were in full retreat towards the Ebelsberg bridge. Attempts to coordinate efforts on this side of the river were well nigh impossible for the Austrians; it also gave the French an edge they were able to take full advantage of through an energetic command. This last factor perhaps more than any other perhaps robbed the Austrians of the defensive victory that should have been theirs.

THE INITIAL ACTION

Massena’s forces consisted of the IV Corps including Marulaz’ Light Cavalry Division and Claparede’s Infantry Division, mixed forces of both French (including Italians in French service) and allied German units, the latter being predominantly Badeners. In the van of the pursuit were the Baden Light Dragoons (Trenqualye) and the 14 Chasseurs the latter of which made contact with the Austrian forces on the morning of the 3rd of May in the narrow defile just north of Scharlinz. Coming upon a battalion of Austrians drawn up across the defile the French immediately drew sabres and charged. The Austrians replied with a volley that killed the officer leading the charge and wounded nine troopers; the French retired having made the classic scout’s sacrifice of blood for information. Although in a good defensive position as they were unsupported, the Austrian infantry quickly withdrew.

Past the defile and moving through a heavily forested area, Marulaz’s Chasseurs were ambushed by a battalion of grenzer hidden in the forest that again forced the French to deploy until the infantry could be brought up. After a brief exchange the Austrians melted back into the woods and the pursuit was resumed. Units of grenzer continued to try and ‘bushwack’ French and Allied units passing through the forest until in one celebrated incident, after being shot at, the regimental surgeon (!) of the Baden Chasseurs lead a troop in a charge into the trees that captured over 50 of the grenzer stragglers who had tried to ambush their column. Grenzer units that occupied villages along the road were winkled out at bayonet point by the vigorous French advance and soon joined the increasing numbers of refugees making their way towards the bridge over the Traun.

The Austrian retreat across the river began to become more panicked as troops both of Schustekhs’ division and the rearguard realised that the speed of the French advance threatened to cut them off on the wrong side of the river. This was not helped by the narrowness the defile on the bridge approaches and the bridge itself that resulted in a bottleneck of men, horses and vehicles all desperately vying to cross the river to safety. The Austrians attempted to delay the French advance by holing up in Sharlinz and Klein Munchen but to no avail; the French either went around them or again forced the Austrian defenders out at bayonet point.

The confusion at the river precluded any coordinated defence of Klein Munchen which might have held the bridge open long enough for an effective withdrawal. Cut off on the other side of the river, surrounded Austrian units began to surrender; a combined battalion of the Spleny and Benjowsky regiments, some 5-600 men , trapped against the river bank laid down their arms.

Official records state Austrian losses on this side of the river at 229 officers and men dead, 400 wounded and over 1000 taken prisoner. Some Austrians refused to surrender and one enterprising uhlan, Trooper Josef Uhlandicki, jumped into the river and swam his horse across. The rest of his squadron followed his example and encouraged by Austrians lining the opposite bank, the squadron together with one officer and 107 half-drowned Gradiskaner Grenzer (who had managed to hold onto the horses tails) were dragged from the river by their comrades. This was an amazing feat given the fact that the river was a raging torrent and few men were able to swim; it showed that in spite of their dire circumstances the Austrians were still a determined and courageous foe.

The first French units to arrive were immediately launched at Ebelsberg, literally bludgeoning their way over the crowded bridge. The blockage of men and vehicles forming a bottleneck at the far end of the bridge did not delay the French; both men and vehicles were unceremoniously dumped off the bridge into the raging torrent below. Later, as more French units crossed the press became so great that any who fell and blocked passage of the bridge, friend or foe, suffered the same terrible fate. Once the grenzer stationed in the houses opposite the bridge realised what was happening they opened fire in earnest on the mad mix of both French and Austrians now pouring off the bridge; the most vicious part of the battle had now begun.

INTO THE INFERNO

At about 11.30 a.m the first French unit across was GB Louis Coehorn’s Brigade consisting of the veteran Tirailleurs du Po and Tirailleurs Corse (the latter also known as ‘the Emperor’s Cousins’). They fought their way into Ebelsberg followed a short time later by other units of Claparede’s Division (Brigades Lesuire & Ficatier). Brigadier Coehorn’s Italian and Corsican veterans sprinted over the bridge in open order, formed up in the dubious shelter of the houses opposite. They then charged through the town, up a steep incline through narrow streets towards the stone chateau that dominated the town’s defences, all the time under a ferocious fire from every window, roof and doorway.

The remaining battalions of Ficatier and Lesuire’s brigades followed behind supporting Coehorn’s advance, sprinting across the final span of the bridge under intense musket and artillery fire. Swinging left and right upon exiting the bridge they proceeded to clear the Austrian marksmen at bayonet point from the houses opposite the bridge.

In spite of gaining a foothold on the western edge of the town, Claparede’s men were soon under intense pressure from a determined defence vastly superior in numbers and supported by a constant bombardment from the massed Austrian artillery on the heights above the town. Coehorn’s brigade charged up the steep hill at the stone chateau where the chateau’s defenders opened fire, leveling the leading section of the French column and shooting Coehorn’s horse from under him; the Tirailleurs could go no further.

The other brigades of Claparede’s division fought their way through the town in bitter hand-to-hand fighting finally coming to a walled cemetery on the edge of town adjacent to the chateau. The French columns advanced to within forty paces of the cemetery whereupon they were met with a devastating volley from the cemetery’s defenders, two battalions of raw militia, the 4 and 5 Vienna Volunteers. A second volley saw them tumble back towards the shelter of the houses, whereupon the Vienna Volunteers launched a determined bayonet charge; at the same time the third battalion of Viennese militia (6 Volunteers) had worked their way around the flank of the French and took them from behind.

Hiller, who had up until now behaved more like an observer than the commanding general, recognised the opportunity presented by the Volunteers’ successful charge and launched the Austrian columns stationed above the town in a series of concentric attacks. The Austrians dragged artillery pieces to the top of the narrow streets and discharged them with devastating effect on the packed ranks of French troops to clear the way for their attack.

Hiller’s plan was to drive the French back over the bridge, set fire to the tarred wood that the Austrian pioneers had piled against the bridge supports then, with the French isolated on the opposite of the river, resume his retreat untroubled by the French pursuit. Although not a terribly innovative plan of action, especially considering his earlier inaction had allowed the French narrow purchase on the Austrian side of the river. As events unfolded, Hiller nevertheless came within a hair’s breadth of achieving it.

The French crumpled before the Volunteer’s assault and were driven back almost to the bridge itself before rallying and finally bringing the Austrian charge to a halt. Opposite the chateau Coehorn’s men were also sent reeling backwards; faced with disaster, Coehorn repeatedly exposed himself to Austrian fire in order to rally his men. They fell back and with two artillery pieces took up a position in the market square and occupied the houses facing. The Vienna Volunteers were repulsed by close range canister and the attack finally degenerated to a murderous fire fight running from the market square all the way back to the bridge approaches. Before they in turn were beaten back, the Austrians took nearly 700 French prisoners including the colonel of the Tirailleurs du Po and two battalion fanions. The savagery of the fighting was witnessed by the fact that the Austrians could not get their guns further beyond the tops of the streets because the numbers of dead and wounded so choked them they could not move the guns forward.

Both sides fought with suicidal intensity as the battle surged back and forth across the town. Austrian artillery fire pouring down on friend and foe alike started to set buildings alight adding to the hellish conditions in the town.

Massena, observing these unwelcome developments from the opposite bank, sent messenger after messenger to Legrand’s approaching brigades urging them to make haste towards the town with all speed. The French were holding on to the edge of Ebelsberg by the skin of their teeth as vicious hand to hand fighting saw opponents hunting each other from attic to cellar, house by house. Amazingly, a detachment of Austrian pioneers fought their way through to the bridge and managed to set alight the tarred wood piled under it, the French were only saved by the strong wind which put out the fire. After venting his spleen against Claparede for ‘putting himself in such a mess’ (!) Massena put together a 20 piece gun line on the opposite bank which finally managed to produce some effective counter-battery fire. At about 3.00 p.m. the first units of Legrand’s division had started to arrive after being force-marched along the road from Linz.

THE FINAL STRUGGLE FOR EBELSBERG

With the arrival of Legrand the final act of the battle for Ebersberg now commenced. To relieve the pressure on Claparede’s hard pressed men an attack on the most crucial part of the Austrian defence had to be made. The stone chateau on the knoll to the right of the French line overlooked the exit to the bridge, dominated the town and thereby anchored the Austrian defence. To crack this defence the stout, well-garrisoned schlöss had to be taken; so began one of the most celebrated French assaults in the 1809 campaign.

As Claparede’s men were being slowly but relentlessly forced back towards the bridgehead, Massena ordered the first unit of Legrand’s division, Pouget’s 26 Légeré, to go to Claparede’s aid. GD Legrand put himself at their head and, using one of Coehorn’s sergeants as a guide, advanced across the Traun bridge. An Austrian 6 pounder battery situated on a rise behind the town adjacent to the chateau was ranged in on the bridge and musket fire swept the bridge’s exit. As Coehorn before him did, Legrand ordered the men to sprint over the bridge in open order; miraculously only six were hit in the 500 metre dash to the relative safety of the buildings opposite. At the village square he met with GB Coehorn who pointed out the chateau that lay out of sight some distance up a steep narrow street and bid him attack it without delay.

Placing his pioneers in front as a tete d’colon, Pouget advanced, the street so narrow that it could barely fit six men abreast. The Austrians held their fire until the lead elements of the French column deployed into the square opposite the chateau. The defenders from IR#59 ‘Jordis’, aided by grenzer marksmen then opened a withering fusillade against the French crowded at the top of the alleyway. Three carabinier officers and 53 men, more than a third of the elite company, fell within minutes.

Above the solid wooden gate was a window protected with iron bars through which a constant hail of musketry was aimed any French who showed themselves past the shelter of the buildings opposite. The carabinier company engaged in a furious but unequal firefight with the chateau’s defenders while the remainder of the 26 Légeré were jammed motionless in the alleyways behind. Grenzer also clambered onto rooves overlooking the streets and poured a deadly fire into the ranks of Frenchmen below who, packed together so tightly, could not retaliate. With casualties rapidly mounting and the attack stalled by the hail of Austrian musket fire from every direction, Pouget knew desperate measures were called for.

He called upon the finest marksman in the regiment, Lieutenant Guyot, to silence the musket fire above the gate. Guyot calmly stepped into the open, carefully aimed at the window above the gate and fired then immediately asked for another loaded musket then another, this way keeping a constant fire against the smoke shrouded target. Other carabinier, inspired by his cool courage, emulated his example with the Légeré in the streets behind busily loading and passing forward muskets, thus creating a continuously discharging line of fire. Men fell by the score but others stepped forward to take their place, even standing on their fallen comrades to get a level shot against the chateau’s windows and loopholes.

Gradually the firing from the chateau diminished until Légeré sappers were able to charge at the gate and axe their way inside. At the same time other sappers had found another side entrance that was undefended and hacked their way through the wooden door; with French simultaneously coming through the front and from behind the remaining defenders quickly capitulated.

While the action at the chateau was in progress the remaining battalions of Legrand’s first brigade (forming the 18 Ligne) had crossed the bridge. The first battalion was sent to clear out the remaining Austrian marksmen in the town while the other two battalions advanced around the town to turn the Austrian’s left flank. Coming to the heights behind the town they formed up in line but came up against fresh Austrian formations that had not been committed to the fighting. The Austrian cavalry, unable to operate in the confines of the town, were stationed so as to stop any French attempt to circumvent the main Austrian defences. Without their own cavalry in support the French advance was once again brought to a halt.

The struggle for the town now over, the fighting centred around the Vienna Gate at the top of the town. Beyond the gate were a series of hedged gardens where the Austrians had deployed most of their uncommitted infantry. Massena himself had by this time crossed the bridge and rode up to the French troops at the top of the town to inspire them to even greater efforts to break the Austrian defensive ring along the heights behind Ebelsberg. Yet again GB Coehorn led his intrepid Corsicans and Italians in a determined bayonet charge through the gate into gardens. Musket fire wiped out the first rank but those following drove the Austrians out of the ga rdens at bayonet point. The Coehorn’s voltigeurs came within 80 paces of the seried ranks of white-coats and proceeded to inflict serious damage on the solid lines of Austrians however, without cavalry the French attack again ground to a halt.

Further French and allied units continued to cross the bridge at the same time as the 26 Légeré, who had advanced to the fields on the northern side of the town, found themselves under heavy Austrian pressure. The Baden Jäegers, who had just made the nightmarish crossing of the river, formed up about 4.00 p.m. and advanced with cool determination to join the beleagered Légeré and threw back the Austrians who were about to overrun them. So relieved to see his German allies was the commander of the 111/26 he exclaimed to his counterpart: “You have saved my honour and my life!” Together the French and Badeners managed to halt the Austrian advance that had briefly threatened French success in the town and managed to secure the French left flank.

A PYRRIC VICTORY

Hiller, seeing that no further progress could be made, ordered the town set ablaze (that is to say those bits not already burning!) in order to stop further French reinforcements from joining their forces already over the river. Confident in the knowledge that the French were successfully contained and little of their cavalry had been able to cross the river, Hiller ordered a general withdrawal. The Vienna Volunteers continued to fight courageously even in retreat, managing to reenter the town and save several artillery pieces that had been deployed earlier at the top of Ebelsberg’s streets.

The French, exhausted by their efforts, conducted only a cautious pursuit; here the Baden Jaegers again acquitted themselves well in their first major action by bringing in over 50 prisoners.

The final part of Legrand’s division, the Baden Line regiments, had by this time also made the crossing but finding the town engulfed in flames were unable to follow the Jaegers and were forced to retire back over the bridge. The Baden horse artillery had deployed on one of the islands in the Traun to the north of the bridge and kept up a heavy fire on the Austrians deployed on the heights throughout the battle. That night the cavalry and the artillery were able to cross the hastily repaired bridge to join Legrand and Claparede’s divisions on the far shore.

The same strong wind that had saved the French by blowing out the flames under the bridge also blew the sounds of the battle away from the ears of th e Emperor who was less than three hours away the entire time the battle raged. At dusk when he entered what was left of Ebelsberg the scale of the carnage and the sight of densely packed blackened prostrate forms lining the streets shocked even the hardest veterans. For a man not noted for his concern for casualties, Napoleon was so horrified by what he saw he ordered all units in the vicinity to cease pursuit of the Austrians and put their efforts into rescuing the wounded of both sides from the still burning town. Although history did not record it, one might well imagine what Napoleon might have said to Massena.

Casualties on the French side are hard to calculate due to the vagaries of French bookkeeping and their tendency to play down their losses. Various sources estimated that they lost in excess of 4,000 men, three-quarters of who came from Claparede’s division. The loss of officers was particularly severe with two colonels killed and three others wounded; because of the high proportion of conscripts officers felt compelled to lead by example and consequently paid a high price for doing so. Of Coehorn’s brigade it was said that the survivors of four battalions had to be combined to make one unit. Losses amongst the Tirailleurs du Po and Corse were so severe that after Wagram these units were disbanded. It must also be remembered that these were amongst the only veteran units on the French side at Ebelsberg, the rest being composed mainly of conscripts (albeit lead by veteran officers and NCO’s).

Austrian army archives put their losses at Ebelsberg at 4,495 with 29 officers and 537 men killed, 56 officers and 1,657 men wounded; and 31 officers and 2,185 captured. This would probably not include all those lost on the other side of the Traun during the retreat from Linz.

Postscript

Napoleon, knowing that the main Austrian army had still to be brought to battle and defeated, had specifically ordered Massena from forcing any heavily defended river crossings in order to preserve as much of his force as possible. He demanded to know just what Massena had tried to achieve by this pointless bloodbath, especially in view of the fact that Lannes had crossed the same river unopposed just a few miles to the north. Massena argued that he had been forced to ‘take the bull by the horns’ because Hiller was close to making good his escape.

Witnessing the ‘butcher’s bill’ for this dubious achievement, Napoleon was less than impressed with this excuse but as Massena was one of his most experienced marshals, whose services he would need, he let it go with no more than a verbal chastisement for ‘poor judgement’. As it turned out, despite the losses at Linz and Ebelsberg, Hiller did manage to cross the Danube with the bulk of his force intact and eventually united with Archduke Charles’ main army. Neither commanding general covered themselves with glory in the action at Ebelsberg: Massena behaved in an uncharacteristically rash way when he ordered a frontal assault against a heavily defended position - he gambled on the confused Austrians panicking and continuing to retreat.

When they did not his gamblers luck very nearly ran out; in the least case his action condemned hundreds of his men to certain death and was at best a callous decision. For his part, FM Hiller lost what should have been a readily winnable battle. As one critic put it, “A man who could fail so hopelessly in such a position…is not worthy of the name of general.”

Hiller’s only saving grace was that he did manage to conduct the rest of his retreat without further serious losses and managed to avoid both the pursuing Lannes and Massena, getting his force largely intact back over the Danube to join the main army under Archduke Charles. Hiller was a soldier of the old Marie Therese school (and, unusually for an Austrian, was a commoner that had risen through the ranks), having been in service since 1763. Old and curmudgeonly, he was a difficult subordinate to Charles with the animosity between them finally surfaced the evening before Wagram whereupon Hiller resigned ‘for reasons of health’, Charles must have been much relieved!

Massena went on to prove his worth and, in spite of a debilitating injury from falling off a horse, successfully conducted operations at Wagram from a magnificent carriage. His cool, calm performance here in direct contrast with (and more than made up for) the rash error of judgement he displayed at Ebelsberg.

More Ebelsburg

Back to Table of Contents -- Kriegspieler #9

To Kriegspieler List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by Kriegspieler Publications.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com