Finally, I have had the chance to put finger to keyboard and write the long awaited second

part of the 1066 invasion of England (gasps and sighs from my legion of loyal fans, I wish).

On the surface, writing a piece on such a famous battle may seem easy. However, the

process of sifting the 'fact' from the fiction can be time consuming and fraught with danger.

In most cases the "road less travelled by" has been taken in the search for historical enlightenment, sometimes coming

up with bizarre alternatives.

Finally, I have had the chance to put finger to keyboard and write the long awaited second

part of the 1066 invasion of England (gasps and sighs from my legion of loyal fans, I wish).

On the surface, writing a piece on such a famous battle may seem easy. However, the

process of sifting the 'fact' from the fiction can be time consuming and fraught with danger.

In most cases the "road less travelled by" has been taken in the search for historical enlightenment, sometimes coming

up with bizarre alternatives.

Norman knight.

As far as the battle of Hastings is concerned there was a temptation to once again pursue the bizarre, investigating things such as Harold's survival of the battle and living his remaining years as a monk. But as this is a historical gaming magazine, that subject may be just out of the subject range except as a Fantasy article (perish the thought). This article really begins with a statement, that on the surface may appear to be quite bold, that the superiority of the mounted Norman knight was not the decisive factor in William the Bastard's victory at the Battle of Hastings.

The decisive factor in the battle was the Norman use of archers, in particular one very lucky shot that felled the English King. This shot was the critical moment that determined the fate not only of Harold, but also his army, which until that moment had withstood the flower of Norman knighthood for nearly a full day.

Harold's image as a military commander has been tarnished by his alleged poor performance in this battle. However, his campaigns against the Welsh in 1063 and his march against Harold Hardrada at Stamford Bridge add lustre to his image rather than tarnish it. Even when his Hastings campaign is examined closely his speed of movement and 'eye' for ground justify him being placed on a military skill level equal to or perhaps even higher than William of Normandy. William's performance at Hastings reeks of pure luck and rather than establishing him as a great military commander, actually questions that status.

The story of the Battle of Hastings has been told, in various forms, far too many times to be repeated here. However, there are certain aspects of the battle that have become 'standards', but as far as this writer is concerned they are standards that deserve critical assessment.

Harold and his army were caught by surprise

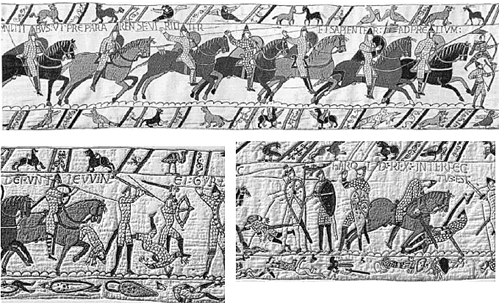

Top: Detail from the Bayeux Tapestry, Norman knights charge past a skirmisher screen of archers

Top: Detail from the Bayeux Tapestry, Norman knights charge past a skirmisher screen of archers

Left: Detail, Bayeux Tapestry. The death of Harold's brothers Gyrth & Lefwyne

Right: Detail, Bayeux Tapestry: the death of Harold.

When the sun rose on that fateful October morning in 1066, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us that Harold found William's army in "full array" on Telham Hill. This part of the story is used to argue that Harold was surprised and forced to deploy his army rapidly. However, Guy of Amiens in his work the 'Carmen de Hastingae' suggests the opposite.

He suggests that the English suddenly dashed from their hidden position in the woods to take up position ready for battle. The timing for this is early in the morning indicating that Harold had made a night march so as to be in a position to ambush William. The Bayeaux Tapestry indicates that on the morning of the battle much of William's army was out foraging, which hardly suggests his army was in full array for battle. Combine these two descriptions with the ability of Harold, with his army, to occupy unmolested, the most defendable piece of ground between Hastings and London and you have an argument that suggests perhaps that William was the one left surprised.

The Feigned Flight

Much has been made of William using the 'feigned flight' tactic to draw Harold's men from their strong defensive position. However, the use of this tactic has been called into question. Delbruck makes a strong argument against the tactics use, suggesting that there is a great danger that the tactic may be mistaken for a genuine flight by the remainder of the army who may then turn and flee as well!

Furthermore, to orchestrate such a manoeuvre indicates that William had a high level of command and control, a level that was exceedingly rare in the individualistic character of feudal battle. Even Harold, whose army was in a compact stationary shield wall formation, is critisied for not being able to maintain control, yet Williams army was spread over a much wider area and constantly moving. In the case of both armies, any orders would have had to be given amoungst what Robert Wace calls "the noise and cry of war".

Saxon Housecarl, spearman.

Saxon Housecarl, spearman.

William of Poitiers elaborates this point when he says that "the shouts of the Normans and of the barbarians were drowned in the clash of arms and by the cries of the dying" making the issue of verbal orders neigh on impossible. Also it must be remembered that William had such great control of his army that at one stage of the battle the Normans thought him to be dead!

Perhaps the most interesting thing to note about the story of the 'feigned flight' is that it is a consistent story among the Norman chroniclers. Granted most of the English who would have been capable of writing the story were dead, (a significant impediment for writing history) but neither William of Poitiers, Robert Wace or Guy of Amiens, all considered major sources of infor mation on the battle, were ever there. They all relied on the stories of those who were at the battle however, there are significant inconsistencies between each account. William of Poitiers credits William with the idea of the 'feigned flight' after seeing the French and Bretons break with Harold's men in pursuit. Guy however alleges that it was the Normans themselves who broke and fled while Robert Wace makes no comment in regard to any troops of William's army breaking.

Of course the story of the 'feigned flight' may have been created as a cover-up for a genuine flight later in the day. For both William of Poitiers and Guy of Amiens one genuine flight may have been sufficient for their stories and the men they were written for. A second story of brave knights running away may have called the bravery of their knights in to question, this may also account for why Wace does not mention the genuine flight earlier in the day.

Harold's Army

The last area to be reviewed relates to the make-up of the armies, particularly that of Harold. Certainly this is an area of much conjecture as we know significantly more about the composition William's army than we know about the army of Harold. This is quite understandable, as many of those who fought with Harold also died with him.

Apart from his force of Huscarles, allegedly numbering approximately 1000 men, the army of Harold is portrayed as being of very poor quality, lightly armed with little or no protective armour. This portrayal ignores two important factors. Firstly, it ignores the existence of the armed retainers of both Gyrth and Lofwyne, Harold's brothers and the retainers of other English nobles in attendance at the battle. These armed retainers were hardly a shire levy but rather trained soldiers.

Norman cavalry line up for another charge up Senlac Hill.

Norman cavalry line up for another charge up Senlac Hill.

The second factor relates to the nature and timings of the battle. Take the following quote from Wace:

- "From nine o'clock in the morning, when

the combat began till three o'clock came,

the battle was up and down this way and

that, and no one knew who would conquer

and win the land. Both sides stood so firm

and fought so well, that no one could guess

which would prevail."

Do you see the problem? The problem lies in that we are asked to believe that an army comprised mostly of unarmoured shire levy would stand firm against the flower of Norman soldiery for six hours. Then the only break for the Norman's comes in the shape of an alleged 'feigned flight' after which the battle still continues till nearly dark.

Furthermore, these same levy troops inflict such devastating casualties on the Norman army that William stays at the battlefield for two days then, rather than advancing toward London, retires to his base at Hastings and spends two weeks reinforcing his army. This must rank as one of the most remarkable feats, by raw unarmoured infantry, in the history of warfare!

The intention is to debunk the myth that Hastings was not just a quick battle but a battle won by superior generalship and better troops. As Oman points out, the critical moment that led to the disintegration of the English army was the wounding of Harold. Certainly, by this late stage both armies, not just Harold's, were significantly weakened. The Normans knights themselves were so weakened that they could not force the English off their ridge. It took a moment that would weaken the resolve of the English, that moment was the wounding and death of Harold not by a noble knight but by a humble low-born archer.

Hastings as a DBA Game

This is, quite rightly, a very difficult scenario for the Normans to win, knights just don't like the guys with pointed sticks.

Terrain

The terrain board should be set up according to the following description. Harold's position is on Senlac Ridge, which is protected on his right by a steep ravine. To his right front is a small detached hill which has to its front a marshy stream. On the other side of the board is Telham Hill. All hills have gentle slopes except for the sides of Harold's ridge where they are steep and impassable. The marshy stream is treated as bad going but is not a defensible feature as it is crossable along its length.

Special Rules

Special Rules

Neither army need to deploy a camp. English elements that force a Norman element to recoil in close combat will pursue one base-length on a roll of 1or 2, but only up to the time where the English lose its 2nd element.

Armies

Norman (#102c): 3x Sp, 4x Kn, 2x Cv (Breton) & 3x Ps.

English (#113) 3x Bd, 8x Sp & 1x Ps.

Deployment

Normans should be deployed in 3 commands up to 900 paces from their base edge. The English should deploy first as a single command on Senlac Ridge. The Norman player moves first.

Campaign Participants in a campaign may include Harold Hardrada (#112) Malcolm of Scotland (#111) as well as the Normans (#102c), Harold of England (#113) and the armies of the Northern Earls (#113).

In a campaign situation Harold's force may mount all his Bd elements and half his Sp elements. Standard practice in the English army was to ride to the battlefield but fight dismounted. This is how Harold arrived at Stamford Bridge so quickly.

Harold Hardrada and William may not communicate with each other for the purpose of synchronising their attacks. Even a simple DBA game of Hastings highlights the problems faced by William and how difficult it is to overcome solid infantry formations. The DBA game also highlights Harold's ability to select a defensible battlefield. When looking at Harold's battle site it is not hard to replace Harold's spearmen with Wellington's squares or William knights with Napoleons Cuirassiers. The only difference is that Wellington had the firepower to defend his ridge while Harold had none.

Sources

Barker P, & Bodley Scott R, De Bellis Antiquitatis, Wargames Research Group, Devizes, 1995.

Contamine, War in the Middle Ages, Basil Blackwood Ltd, Oxford, 1985.

Delbruck. H. History of the Art of War; The Middle Ages. Greenwood Press, Westport,1982.

Denison, G T. A History of Cavalry from the Earliest Times. Greenwood Publishers, Westport,1977.

Fuller, J F C. A Military History of the Western World; Volume 1; From earliest times to the battle of Lepanto. Da Capo Press, New

York, 1954.

Freeman E A, The History of the Norman Conquest of England, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1875.

Howard, M. War in European History. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1976.

Lemmon C, The Campaign of 1066 in the Norman Conquest, Eyre & Spottswoode, London, 1966

Logan H R, The Norman Conquest, Hutchison University Library, Oxford,1965.

Oman, C W C, The Art of War in the Middle Ages: AD 378 - 1515. Cornell University Press, London, 1976.

Wood M, In Search of the Dark Ages, BBC, London, 1981.

Note on Sources

So much has been written about this battle that it is often difficult to separate good from rubbish. The sources used here are a mix of more modern thoughts as well as works by writers such as Oman and Delbruck that are from the 1890's. Some critically examine while others focus on one particular person and argue that persons role in the battle as pre-eminent. Most of these sources do quote extensive sections of primary source material such as the 'Anglo Saxon Chronicle' or the work of Robert Wace for example. However, that doesn't mean that writers using the same source come to the same conclusion, but that's history for you!

Related:

Back to Table of Contents -- Kriegspieler #10

To Kriegspieler List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by Kriegspieler Publications.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com