"It is with artillery that war is made!"

--EMPEROR NAPOLEON

Recently, (by that I mean the Australia Day Long weekend), I

was participating in a HUGE multi-player Napoleonic battle

and discovered how little many players actually know of the

effect artillery played on the 18th & 19th Century battlefields.

"SHOCK and HORROR!!!… This situation must be

addressed!" I thought, and who better to do than I; being an

artilleryman in real life.

Recently, (by that I mean the Australia Day Long weekend), I

was participating in a HUGE multi-player Napoleonic battle

and discovered how little many players actually know of the

effect artillery played on the 18th & 19th Century battlefields.

"SHOCK and HORROR!!!… This situation must be

addressed!" I thought, and who better to do than I; being an

artilleryman in real life.

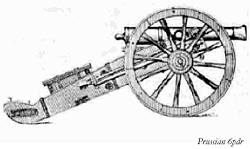

Prussian 6pdr.

So I sat down and set fingers to keyboard and what follows is the result. I originally penned this paper as part of an essay I had to write as a sergeant in the Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery ("Effective Writing Training" they call it), but figured that with some modification it could easily be adapted to the understanding of the "masses". So, without further ado…

INTRODUCTION

In this paper I intend to explore the use of artillery during the Napoleonic Wars and in doing so hopefully give the reader some insight into how artillery impacted upon the horse and musket battlefields of 1800 to 1815. I will use the British Royal Artillery as an example to explain most of my points, but I will also refer to the employment of the big guns and howitzers of the other continental powers of the day. As well I will include the pieces massed by the armies of Austria, Prussia, Russia and of course, Imperial France; commanded by the man whom many regard as the greatest of all gunners, Napoleon.

THE EQUIPMENT

The artillery pieces used during the Napoleonic Wars can be divided into two major groups, guns and howitzers. You could also add to this rockets used by the Royal Horse Artillery and also the Austrian artillery , these early rocket systems were never widely used nor that effective. It was in fact at Quatre Bras on the 17 June 1815 that the rockets of one Royal Horse Artillery Troop demonstrated just how erratic these weapons could be. On this occasion the Anglo-Dutch army was withdrawing towards Waterloo and being harassed by French cavalry and horse artillery. As the English horse guns had ran short of ammunition it was decided, reluctantly, that the rockets of the Rocket Troop be used to conceal the shortage.

Apart from a lucky initial shot that destroyed one of the French guns, most went astray. Bernard Cornwell described the situation in his novel "Sharpe's Waterloo" thus, " …the first rocket arched in fire across the damp valley to leave a serpentine trail of smoke. The missile fell toward the French guns, then the fuse inside its head exploded and a rain of red hot shrapnel crashed down to slaughter every man in a French gun crew…. Encouraged by their success, the rocket artillery fired a whole barrage. Twelve rockets were fired from twelve metal troughs angled upward on short legs… they wobbled at first then acceleration hurled them on. Two streaked straight up into the clouds and disappeared, three dived into the wet meadow where their rocket flames seared the grass as the missiles circled crazily, five went vaguely towards the French but dived to the earth before they could do any real harm, and two circled back towards the English Cavalry who stared for a second before scattering in panic….."

Gunner, the Honourable Artillery Company, 1804.

Gunner, the Honourable Artillery Company, 1804.

The variety of guns and howitzers was immense: "Adye's Bombardier and Pocket Gunner" (London 2nd Edition, 1802) the artillerist's vade mecum of the period lists no less than 64 distinct types of ordnance (including mortars), though only ten of these were in common use for field service. For the field batteries the light 6 pdr and the 5-1/2 in. howitzers were the standard weapons.

After failing in the Peninsular War the original 8 and 10-in. were withdrawn from service, the 4-1/2 in. and 5-1/2 in. remaining in use. Eventually, the 6 pdr. was replaced in the foot batteries by the vastly superior 9 pdr although it remained in service as a horse artillery piece. These details apply only to the Royal Artillery and the Royal Horse Artillery however, similar situations prevailed in the artillery branches of the other major European powers.

For example; Napoleon's favourite arm was equipped with 4, 8, and 12 pdr guns, 6 and 8 pdr howitzers in the field artillery, while the position and siege artillery consisted of 12, 16, and 24 pdr's and 24 pdr howitzers. The horse batteries were equipped similar to the foot gunners. Apart from the actual guns and howitzers the batteries would also have a large train attached to them consisting of mobile forges and wagons for forage, spare parts, spare barrels and wheels, artificers tools and farriers equipment.

CONSTRUCTION OF GUNS/HOWITZERS

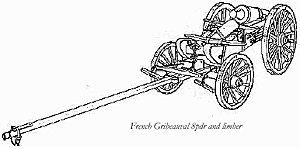

In discussing construction let us look now at the artillery arm of France. As Napoleon was to declare, "The finest and best composed corps in Europe!" The Emperor was not only commenting on the esprit de corps of the highly trained officers and men, all versed in the scientific art of gunnery, but also on the equipment. Designed in a simple, sturdy yet interchangeable form by the great master of artillery, Jean Baptiste de Gribeauval (1715-89); as far back as 1768 guns were normally made of bronze, although iron guns, (less prone to distortion when hot) were employed for siege work.

The carriages were made of two suitable shaped pieces of wood or "cheeks" parallel to each other and joined with horizontal sections of wood. At the front the lowered part of the cheeks were bolted to the axletree to which the wheels were fitted and the rear part of the carriage was designed to sit firmly on the ground. Any areas on the carriage that were prone to hard wear were reinforced with iron strapwork. The barrel was attached to the carriage via its trunnions resting in iron reinforced trunnion holes. The barrel was kept firmly in place by closing over the top of the tunnions a thick metal strap know as a capsquare and held in place by a hinge at one end and a loop and pin at the other.

The carriage was also fitted with various bars and loops for manhandling and for stowage of drag ropes, rammers, sponges, buckets and other equipment. Howitzer carriages maintained the same overall appearance and construction, differing in having a slightly shorter trail (and barrel - of course!).

ORGANISATION

The Royal Artillery was not strictly part of the army during the period we are exploring in this paper. It was in fact under the direction of the Master General of Ordnance and the Horse Guards. Thus this branch had greatly different characteristics most notably in the level of training given to their officers whose promotion was by seniority and not, as was the case with the infantry and cavalry, partly dependent upon the purchase of commission system.

The Corps HQ at Woolwich, where the artillery depot and academy were situated, was controlled by the Deputy Adjutant-General, Royal Artillery, whose staff consisted of one assistant and five clerks - four of whom were mere sergeants. Amazingly, it ran the entire artillery establishment. Consequently, the Royal Artillery resembled a close knit, if somewhat large family, justifiably proud of its professional competence, an attitude which tended to distance artillery officers from those of the other services.

Compared with the vast numbers of cannon fielded by the armies of continental Europe, Britain's artillery arm was quite small, despite the expansion that occurred during the Napoleonic Wars (there was 274 artillery officers in 1791, rising to 727 by 1814). The necessity that all officers of the RA be highly trained meant that expansions could not be effected quickly. The initial shortage of trained officers led to the retention of battalion guns long after they had been recognised as being outmoded (more on this later). In 1803 the Royal Artillery consisted of eight battalions each of ten companies. A ninth was formed in 1806 and a tenth in 1808. Battalions did not serve in the field as complete units but were deployed in company sized brigades and attached to infantry or cavalry brigades.

The term "battery' - a 'brigade' usually consisting of 6 guns was used to describe a gun position rather than in the modern sense.

The establishment of each of these brigades or companies in 1808 was officially 2 captains, two 1st lieutenants, one 2nd lieutenant, 4 sergeants, 4 corporals, 9 bombardiers, 3 drummers, and 116 gunners. These would be divided between 5 guns and 1 howitzer, although units composed entirely of guns or howitzers were not unknown. The Royal Horse Artillery was formed in 1793 as a support for cavalry, and all gunners were either mounted or riding upon unit vehicles, (as opposed to the 'foot' gunners marching). Foot companies were generally known by the name of their commander (eg. Geary's company) and horse brigades either by this method (eg. Mercer's troop) or by their designation-letter, (eg. 'A' Troop). To add to the confusion, the Austria's referred to their artillery sub-units as 'batteries' either "position"', "brigaden" or "kavallerie".

French and Russian artillery units were, generally speaking, larger than their British or Austrian equivalents.

Battalion Guns

Now to the battalion guns but first, what were "battalion guns"? Basically they were light field pieces attached to the infantry battalions and cavalry regiments to provide immediate fire support for that unit. Infantry battalions trained an officer and 34 men to handle the unit's two 6 pdr guns and cavalry regiments had an officer and 18 men to man their 2 'galloper guns'.

The system was not a success and had become virtually extinct by 1799. Generally the guns became more of an encumbrance than an asset. French General Lespinasse wrote in 1800, " If you want to prevent your infantry from manoeuvring, embarrass them with guns". Until 1798 the RA provided personnel to train and supervise the battalion gunners. Another reason for the demise of the battalion guns would have to be the theory of massing your guns, (battalion guns being contrary to this). The Prussian's persisted with the battalion guns up until the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Does this sound familiar?

More recent examples include the German Wermacht's "Kampf Gruppen" of the 2nd World War and even the Australian Army's recent trial of embedding guns in its battalions. It would be hard to make such a comparison today in regards to the impact on the mobility of an infantry battalion - it didn't seem to effect the movement of the Wehrmacht's 'Kampf Gruppen'! But surely the theory of "Mass your guns!" still holds true …or does it? Early in the Napoleonic Wars the Austrians failed to subscribe to this theory and they paid the price in suffering crushing defeats at the hands of that great gunner, Napoleon, Austerlitz being the obvious example.

EMPLOYMENT

Let's look at the employment of the artillery during this period. Firstly, just how effective were the guns and the howitzers of the day? To give just one example, at Austerlitz in 1805 the fire of the Imperial Guard artillery was described by Russian and Austrian commentators as "ploughing through our long columns, carrying with it death and consternation". At the battle of Eylau in February 1807 a "Grand Battery" of seventy two Russian guns opened fire on a French division at close range and inflicted 5,200 casualties in just over 5 minutes. The French described the Austrian bombardment of Aspern village in 1809 as if it had been "…erased by a hail of (cannon) balls, burned by howitzer shells, choked by the intermingled dead…" From these descriptions you can readily see that artillery had a devastating effect on the Napoleonic battlefield.

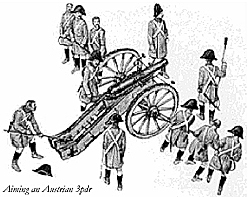

Aiming an Austrian 3pdr

Aiming an Austrian 3pdr

As is the situation today, the role of artillery was to provide fire support on the battlefield. In the attack the guns were mainly used as a battering ram, ie. they would be massed at one point on the battlefield and literally blow a hole in the enemy line prior to the infantry assaulting, who in turn were usually supported by the cavalry and the horse artillery. Once the breach had been made by the artillery and infantry, cavalry would flow through, complete the victory and then conduct the pursuit. Favoured tactic of the day was to threaten the enemy infantry with cavalry and force him to adopt a battalion square formation.

Once this was done the horse artillery (and foot artillery if applicable), would in turn reduce these large targets into piles of dead and maimed soldiers. If the infantry attempted to change into a formation less susceptible to artiller y fire the cavalry would rush in and hack the foot soldiers down with sword, sabre or lance. This tactic was only viable, however, if the enemy lacked cavalry of his own to counter this manoeuvre or if he sufficiently supported his infantry with his artillery. The role of the guns in defence was to break up or counter these attacks, with the horse artillery serving as a mobile reserve, used to help stem any breakthroughs or assist in any counter-attacks.

This all sounds very simple but as we know the application of a theory on a fluid, dynamic and confused battlefield is never that easy. Firstly, there were the problems of bringing the fire of a massed battery to bear on the target. In most battles of the period the fighting would fall into phases lasting approximately one half-hour each. At the end of that time either one side would have achieved its objective or its attack had been halted, and there would be a pause as each side attempted to regroup before starting the next phase of the battle. During this phase of combat an individual would fire something in the vicinity of 20 to 30 rounds of ammunition. In theory, the guns could fire up to 60 rounds in this time however is unlikely that so many rounds would be correctly laid (aimed) with the many problems that the detachment commanders had to contend with. In particular dense clouds of white gunpowder smoke would engulf the battlefield and obscure the target at frequent intervals.

So who was primarily responsible for the performance of each gun? The answer is the "Number 1". The battery commander and one other officer were of course on the gun position, and they would give the initial orders but they could not be everywhere. They certainly correct gross errors, but with the deafening noise, swirling clouds of white smoke associated with each discharge and the general excitement, it was impossible for them to exercise more than general supervision. The perfor mance of each gun and the matter of whether it was a contributor or simply consuming ammunition depended almost entirely on the Number 1 gunner, the gun's detachment commander.

So what did the "Number 1" have to do? To begin with, he was in command of the gun detachment or crew and in the days of highly explosive and exposed gun powder, that meant the complicated drill of sponging, loading, priming, and firing had to be carried out meticulously. Any failure to carry out the correct drills could have disastrous consequences - assuming that he had a competent detachment requiring no more than a watchful eye to ensure they didn't do more harm to themselves than the enemy!

Next, he had to lay (or aim) the gun himself. Laying for line wasn't any real problem as it was simply a matter of aligning the gun with the target by use of a handspike, but laying for elevation required a great deal of skill and experience. The round being fired, the main problem for the Number 1 was observing the fall of shot. This was frequently a real problem as many guns were likely to be firing on the same target which was frequently hidden by smoke or moving over broken ground, nor in the days of solid shot were there any shell bursts to catch the eye.

From this we can see it was not simply a case of lining the guns up wheel to wheel and cutting loose. In actual fact the guns were normally deployed in a staggered alignment, normally 30 or more yards apart; an 8 gun battery would occupy up to 300 yards frontage. This was done for two main reasons; to allow for a greater play of the individual guns and to keep guns far enough apart to protect them from adjacent explosions or direct hits. Conversely, guns could be jammed into an area about 15 yards frontage each - 14 yards was about the minimum space that allowed the gunners to work efficiently between guns.

French Gribeauval 8pdr and limber

French Gribeauval 8pdr and limber

Generally speaking, a gun could throw a round about a mile with a maximum effective range of 800 to 1200 yards. An experienced Number 1 would aim for first graze to occur just in front of the target, allowing the ball to go careering through the target at shoulder height or less. The idea was that the round would strike the first man at the ankle or shin then the rank behind him at the knee. The next chap would wear the solid shot in the groin or belly and the next soldier would be cut fairly in half at the belly. Hardly slowed, the projectile would crash into the next unfortunate at chest hight and then start taking heads off. The round would sail safely over the next few ranks and then reverse the trend as it descended amongst heads, shoulders, chests, bellies etc, etc…

Casualties were not only caused by direct hits, but also by bone, sinew, broken and busted muskets, entire limbs, and rocks flying at hundreds of miles an hour into nearby soldiers. If all went well (from the gunner's perspective) a roundshot could continue to bounce through to formations further back and cause still more casualties.

As general rule, artillery doctrine of the day mandated that targets be confined to infantry and cavalry as it was very difficult to suppress an artillery battery. On occasion, however, massed batteries could silence enemy guns by sheer weight of fire.

BIBILOGRAPHY

P. Haythornthwaite "Wellington's Specialist troops." OSPREY Men at Arms Series

W.Y Carmen "The Royal Artillery" OSPREY Men at Arms Series

R Wilkinson-Latham "Napoleons Artillery" OSPREY Men at Arms Series

B Cornwall "Sharpe's Waterloo" COLLINS 1990

Back to Table of Contents -- Kriegspieler #10

To Kriegspieler List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by Kriegspieler Publications.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com