Royalist

Royalist

Fieldword: "King and Queen"

Prince Rupert of the Rhine

6500 Men

Parliamentarian

Fieldword: "Religion"

Sir John Meldrum

6000-7000 Men (Outnumbered in Cavalry)

During mid 1644, a hastily assembled ďarmyĒ sped through the countryside, a mission in their minds, but unknown to their oblivious enemy.

Prince Rupert was at the head of this Royalist prong, which cut sharply through enemy territory like a knife. No rebel commander seriously took this force as a threat, nor did they imagine in their wildest dreams that it could mix together and fight effectively.

This crack force had been assembled on the move, to allow the Royalists to move North freely and raise the siege of York. Newark, which was a key in the Royalist communications with the North, was under siege and needed urgent help.

King Charles I had backed the forceís objective, writing with great concern on March 7th, asking Rupert to what he could to save Newark.

From this summons, Rupert despatched hasty orders to Henry Hastings, Lord Loughborough, whose family held lands in the midlands. Ordering Loughborough to send 700 horses to Bridgnorth, Rupert was preparing in advance, for the need to carry soldiers across to his rendezvous with speed.

Preparations

Rupert himself was in his command post at Chester, when another letter arrived for him from the King. He read that the King wanted him to send immediate aid, without delay. The King was fully aware of how important Newark was to his cause. After he had scanned the letter, Rupert sent Sir William Legge (Honest Will) his close friend, to Shrewsbury, telling him to collect up as many musketeers as he could from its garrison, despatching them to Bridgnorth.

As Rupert himself rode into Bridgnorth, towing along 3 pieces of artillery and his own and another regiment of horse on 15th March, he found 1100 musketeers loyally waiting for him.

Legge had done his job well and the musketeers and their commander, Colonel Henry Tillier, had been despatched by Legge, down the River Severn in barges for speed.

From their launch pad in Bridgnorth, Rupertís force catapulted through Wolverhampton and Lichfield, to Ashby de la Zouch, taking additional men from each garrison as he went. Although dangerous for the garrisons, this force was only temporary and the only enemy threat was the force which he was aiming to encounter.

Rupert scanned his men in Ashby on 18th March, and after nearly 50 miles march, he counted 3400 men. At that point, Lord Loughborough joined him with 3000 men, bringing the total force to an equal split of 3000 foot and 3300 horse.

So far so good and the enemy commanders were still blissfully ignorant. Sir John Meldrum, the rebel commander who was besieging Newark, was aware of Loughborough moving around the area, but he did not believe it could be any threat. Even the Roundhead Lord General, the Earl of Essex, knew of Rupertís initial movements, but had not suspected or at least gave much concern to them.

Indeed Rupert had gone to great lengths and used his vast skills at improvising and leadership to prevent any enemy suspicion. Once more Loughborough was given the task of carving gaping passages through the hedges and fields, creating a clear and direct route to Newark, avoiding all the major roads and monitored points.

By evening on 20th March, Rupert and Loughborough were a mere 10 miles away from Newark, at Bingham. Still the enemy were ignorant, it seemed amazing to the Royalists that their Prince had pulled off such a bold move and this faith in their commander would have been the strongest force in bonding several groups of fighting units, which had not fought together before. Even greater about this fact, was that some raw recruits, some who had never been off garrison duty and above all, men from many different counties.

Ever planning ahead, Rupert was determined not to stop until he had seen a full success, which included defeating Meldrum as well as relieving Newark. Deciding on an early start, Rupert told his officers of his intention to cut off Sir John Meldrumís line of retreat, by launching his attack from the South of the town.

Meanwhile in the Roundhead camp, Meldrum was in panic stations. That night, very late in the day, he had just received his first piece of news, which told him Rupert was definitely aiming at him.

John Hutchinson, the Governor of Nottingham, had sent the message and Meldrum immediately decided to draw up his forces to the North East of Newark, hoping to secure his retreat to Lincoln.

So as Meldrumís men moved to this point, Rupertís observed and informed their Prince. Rupert was asleep at the time and as he awoke, he saw Will Legge and told him of a dream he had, in which Meldrum had been defeated.

Thinking the worst, that Meldrum was fleeing, Rupert set out from his headquarters at 2am, with the ever present Loughborough and some troops of horse, intending to hold Meldrum in place, until the main Royalist army could arrive.

Battle Positions

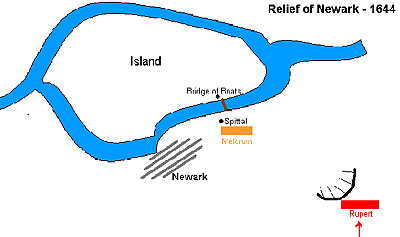

Meldrum had fortified a medieval hospital called the spittal, just behind his position and also formed a bridge of boats to secure his retreat onto the island if necessary.

As Rupert reached this situation at Beacon Hill, dawn was just breaking when he chased off some of Meldrumís horsemen, who had begun occupying the high ground of the hill.

Once it was lighter, Rupert got the chance to observe his prey squirming below, but by no means an east target. Meldrum had two large bodies of 1500 foot in his front, while he was moving his gums around behind. Ever impatient, but correctly confident, Rupert grasped at the nettle of surprise and formed up his horsemen in three lines, as can be guessed, leading the first himself. Loughborough headed the second, whilst Gerrard headed the third.

The Royalist main body hove into view by 9am, just in time to see Rupert charge down the slope towards Meldrum, getting faster by the bottom and slamming full force into the front of the enemy horse. Although superior in numbers, Meldrumís men recoiled from this famous assault tactic of Rupertís and dispersed to the wind. Two regiments were made of sterner stuff however and put up a fight, trying to counter attack.

During this attack, Rupert and a few men found themselves surrounded. The crucial point in the battle was now and to many, it seemed as though Rupert would be killed.

Three enemy horsemen assaulted him, but during the melee, he thrust one down with his sword, whilst his loyal French attendant Mortaigne, who had followed him since the start of the Civil War, shot another with his pistol.

Just then, the last man grabbed hold of Rupertís collar and as Rupert battled like a lion, his situation was grave indeed.

At that moment, Sir William Neale saved the Princeís life by cutting the enemyís offending hand clean off, with one swipe of his sword.

Without further ado and any hint of inconvenience, Rupert gathered his men together and led them to a charge, scattering the enemy once and for all.

Meldrum seeing that the tide of battle was chasing him, ordered the remains of his horsemen onto the island, crossing via the bridge of boats, but left his foot supported by his guns, in the spittal.

On top of the hill, Tillier took the Royalist musketeers and tried unsuccessfully to capture the bridge of boats. Assaulting the spittal would be costly and Rupert paused for the first time, to weigh up the situation.

During the break, Rupert managed to get 500 horsemen over to the island, before Sir Richard Byron sallied out from Newark, capturing the fort which would cover Meldrumís retreat to the North. By now, in effect, Meldrum was bottled up on the island, under siege and in a fruitless position.

Suing for terms next day, he marched away with pikes, swords and colours, but left 11 brass cannon, two mortars and 3000 muskets. The equipment was welcome to Rupert, who was before this march, trying to fit out an army to save the North of England for the King.

Victory and jubilation was not enough to make Rupert sway from his strict moral code of honour and in marching away, the Roundheads were plundered by the Royalists, but Rupert rode in amongst the offenders in his army, sword drawn and personally returning an enemy standard to its officers.

Rupert had lost 100 men, but gained much needed equipment for his impending march North. He had relieved Newark, wiped out the threat of a major enemy force and also caused Lincoln, Gainsborough and Sleaford to be abandoned by the Kingís enemies.

Back to Table of Contents -- King or Parliament #2 GJ

Back to King or Parliament List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Mark Turnbull.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com