It was just after 11am on Monday 24th July 1643, when a lone trumpeter rode towards the magnificent city of Bristol. The trumpeter was the King’s nephew, Prince Rupert’s, but the city wasn’t.

England in 1643 was like a stranger to the ghosts of the Armada days, who remembered a glorious nation, ecstatic at its victories over foreign Princes and joyful in its love of its Monarch, who had helped them save the country from Spain.

The unthinkable had happened and England was now at war, but not with Spain or France, with itself. Brothers and friends fought each other and families’ split apart after a decision, King or Parliament, was made; perhaps the most difficult question in someone’s life.

England tore itself apart over the question of power, should the King be allowed to exercise his lawful right to control the army and have a Parliament subservient to him, or should Parliament have the power, with the King as a hollow figurehead, risking the petty squabbles of jumped up commoners?

The question of course was more in depth depending on what men thought was important. Which side would best defend their religion, which was more autocratic, who had God on their side and even who would be more likely to win. These questions shaped peoples decisions, but it was not at all an easy decision to make.

After lagging behind, the Royalists eventually caught up to Parliament in recruiting and the sides were evenly matched when the first battle was fought. Now, nearly one year into civil war, the Royalists looked as thought they would put a timely end to the dispute.

The King had missed out on several chances of capturing London, but in 1643, he had still won a string of six battles. Now Rupert and his army stood before Bristol, the second city of the Kingdom, ready to pounce.

The trumpeter, Richard Deane, was a mere formality and carried a demand for surrender to the Governor, Nathaniel Fiennes.

Fiennes replied he, “Could not yet relinquish that trust until he was brought to more extremity.” Rupert and his fire-eating spirit commenced the preparations of placing his guns on the city and skirmishing with the garrison until well after night fell. Little was achieved that day, or during nightfall.

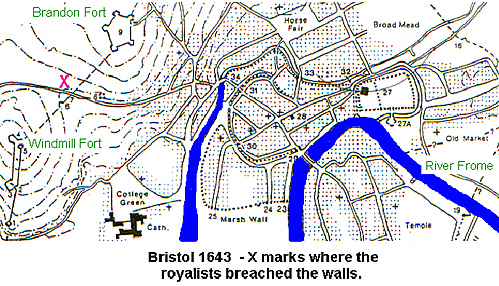

Bristol was surrounded by the River Frome, which flowed into the larger River Avon. As such, the natural defences complemented the man made ones and several forts interspersed the city walls.

After fighting on the Tuesday around the north side of the city, Rupert crossed the river to meet his brother, Maurice and Lord Hertford, the commanders to the south.

Eyeing Up

They opted for a full assault the next morning, rather than the full drawn out siege. Rupert wanted a quick victory; he knew Bristol was at its most vulnerable after the recently nearby defeat for the Parliament. He knew well that Fiennes was not the strongest of men and most importantly, his keen sense of intuition would have spotted the half hearted, defiant response to his demand for surrender.

At the meeting of officers, Rupert told them all his plans. They were to keep the enemy awake all night by synchronised small attacks in different places, weakening their spirit and energy.

At dawn, they would mount a full assault, the signal being the firing of a cannon. Once the tactics were out, the next thing was recognising their own side. Rupert’s password for the day was, “Oxford,” and all men would wear a white strip or necktie.

All was set and now it was a waiting game until the morning. The plans were reinforced and everyone knew their job and mission. By dawn, the men would have got into their positions under the blanket of darkness and cannons and equipment would have been brought up. Unfortunately, over enthusiasm gave the first problem to the Royalists.

At 3am, the Cornish under Maurice and Hertford went in far too early, causing all Rupert’s careful planning to be thrown out of the window. As the Cornish in the South advanced, the Royalists in the North, began to rally and get into their positions to advance, caught out by their counterparts. Rupert hastily ordered the signal shot of advancement and the whole army then began their attack.

As Rupert began to attack in the North, he was unaware that in the South, the impetuous but brave Cornishmen were being mauled.

The Cornish officers suffered losses and Maurice rode through them, rallying and telling them that Rupert had broken through. Rupert had not had any more success than Maurice in reality. Lord Grandison and Colonel John Owen were wounded, two good officers under Rupert. For one and a half gruelling hours, the whole of the Royalists fought with no showing of a breakthrough.

As dawn approached, the Royalist attack in the South had failed and they had come to a standstill, with two out of three of the brigades in the North in the same position.

Then after time out for planning and assessment, the Royalists of Wentworth's brigade decided to attack the weak line between Brandon Hill and Windmill Hill forts. Exposed like a sore thumb, the exhausted but furious Royalist’s eyes were drawn to a resolute stand and the dead ground at the base of the forts gave protection and cover. Rupert rode through his army, bolstering moral and contaminating his men with his own fearless determination to succeed despite the desperate turning of the battle.

Knife Edge

After a while, the Royalists soon managed to cross over the wall and enter the defences, although still in an uncertain position. A series of luck and well-times actions catapulted the cavaliers into some of the forts, driving the defenders back into the city.

One officer, Lieutenant Colonel Littleton rode along the walls with a fire pike, setting panic into the moral of the defenders. At last a breach had been made, enabling the rest of the cavaliers to follow it up.

His good friend Will Legge carried the jubilant news to Rupert. Rupert was with Belasyse’s tertia of foot and once he learned of the advantage and the ambiguousness it was in, he quickly led the foot up to the breach himself. One he had seen them re-enforced, Rupert rode back for more men. It was on his return journey that his horse was shot from under him and Rupert, without any hint of interruption or inconvenience, marched away on foot to complete his mission.

As another fort, Essex-work fell, the cavalry had entered the breach in support of the foot. By now, Wentworth and his men had got as far into the city to be able to set alight to the ships and houses. After he sent word asking for permission, Rupert replied with a definite negative; he wished to preserve the city as best he could.

In the Bag

As the fight moved further into Bristol, the cavaliers found they could move their guns closer to the city in support and Rupert soon used his keen eye to push his command post into the breach made earlier. He then rode on a fresh horse, directing the operation and moving men to support the main area’s of attack; that on Frome Gate.

Rupert’s command post was still within range of two forts, which had been cut off by his troops relentless advance. Deciding discretion being the better part of valour, they only put up token firing. Each fort knew the more they fired, the worse would be their treatment when the inevitable Roundhead defeat came.

Rupert saw that although the assault seemed to be going well, that events could just as easily turn, so he ordered 1000 Cornishmen from the South to march North and attack the forts still holding out within the Royalist lines.

Meanwhile inside the town, Governor Fiennes was having a nightmare with the moral of his defenders. Although he issued orders, which made sense, he failed to inspire any confidence and men saw his unease and inexperience.

Fiennes delayed and then ordered a retreat from the line, which the Royalists had breached, causing widespread dissatisfaction. After soldiers cried out of their dishonour, Fiennes commanded the retreat to within the main city upon pain of death.

At this point, Fiennes seems to have been overcome with inertia, for he left the men in the streets of Bristol without further order, for over two hours. During this time, many rode away and others went for food, so that when his orders finally came, only 200 of the whole pre siege numbers of 1000-1200 turned up. Fiennes was reduced to blind panic.

For Rupert’s men, the going had again become tough and they were pinned down in street to street battles, cavalry and soldiers exhaustingly trying to fight their way through narrow streets, being picked off by determined resistance.

Fiennes sent a drummer with an offer of parley, but Rupert suspecting foul play, declined to halt his troops and lose the advantage, as well as give the enemy time to recover. Only at 11am that morning did Fiennes order his garrison to make a sally against the royalists, which they did with some success, forcing the fatigued royalists to stop. Fiennes then sent another drummer asking for negotiations, which Rupert seized on.

Fiennes found the terms harsh but agreed to them, his men handing over all their arms and colours, ammunition and cannons.

As the Roundheads marched out the next day, they left earlier than agreed, causing the Royalists to jeer and attempt to plunder them. The guard assigned by Rupert to Fiennes and his men were unaware of their early start, but Rupert and Maurice soon learned and rode out amongst their men, drawing their swords to them and threatening them to obey the honours of war.

After nearly 10 hours of fighting, Bristol, England’s second greatest city had surrendered to the King, providing stores, supplies, money, moral and it allowed the Kings war effort to continue.

Tribute to the success should be paid to the able and brave Royalist commanders who failed to see the fruits of their proud work; Lord Grandison, Sir Nicholas Slanning and Henry Lunsford. A great loss combined with a great victory.

Map

Back to Table of Contents -- King or Parliament #2 GJ

Back to King or Parliament List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Mark Turnbull.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com