Most historical gamers concentrate on the big periods: World War II, the American Civil War, the Napoleonic period. A few look to the Ancient or Medieval worlds, but even therein the frame of reference is usually restricted to popular, well known opponents and events (Roman campaigns, for example). There are, however, several very interesting periods and locations which gamers often ignore. One such, especially for medieval gamers, is the Hansa of northern Europe.

Most historical gamers concentrate on the big periods: World War II, the American Civil War, the Napoleonic period. A few look to the Ancient or Medieval worlds, but even therein the frame of reference is usually restricted to popular, well known opponents and events (Roman campaigns, for example). There are, however, several very interesting periods and locations which gamers often ignore. One such, especially for medieval gamers, is the Hansa of northern Europe.

This powerful merchant confederation not only reshaped the economic landscape of the north Europe, it had a profound impact on the political landscape as well; the Hansa fought several wars against sovereign national powers and won. The article below attempts to acquaint the reader with some basic history of the Hansa; and perhaps inspire the interested gamer into recreating some of the conflicts of this rather odd economic/political confederation.

Historiography of the Hansa

There is a wealth of primary source material for the Hansa, shedding light on most aspects of life, both within the Hansa towns and for the Hansa merchants abroad. These sources, both literary and archaeological, support the large amount of historical inquiry that the subject has inspired.

The archaeological sources have grown greatly in number during the past 30 years. The discovery of cogsites in varying degrees of preservation, and the redating of various older finds has given naval archaeologists large amounts of data that was simply unavailable before. This data has led to many to examine the continuity of the boat building tradition in Northern Europe and gain further insights in to the capabilities of the vessels which carried Hanseatic goods throughout the Baltic and North seas.

A large number of buildings from the era of the Hansa have survived, within the Hanseatic towns themselves as well in the Kontores established abroad. In particular, the London Steelyard and the Bergen German quarter remain in good repair, allowing accurate measurements of the size and estimates of the purpose of the various buildings. The most important kontores, that of Bruges, has left no buildings or structures behind. The merchants and journeymen of that community lived among the general populace, quite unlike the almost monastic sequesteringof the communities in London, Bergen and Novogorod.

The Hanseatic towns furnish us with a broad view of Hanseatic life. The surviving structures represent nearly every aspect of life in the Hansa. Cathedrals and town halls represent the centers of the towns both religiously and politically, they are balanced by the strong fortifications, warehouses, and cranes which show the practical working side of the Hansa merchants. The picture is rounded out by the many private homes which survive with their distinctive gabled roofs. Many of these are still occupied and they give us an excellent view of the environment in which the merchants conducted their trade and lived their lives.

We are equally fortunate in the range of literary sources which have survived. A large number of treaties, royal edicts, and other official correspondence between the various towns of the Hansa and the foreign governments with which they had dealings exists, alongside an equally copious amount of correspondence that remained internal. These official documents are complemented by many private letters and notes which have survived. These provide a glimpse into how the Hansa was perceived by the Hansa members and those they dealt with.

Our view of the culture of the Hansa come from very different sources. Several Hanseatic diaries have survived, these personal accounts not only provide us with details of the public activities but the everyday difficulties as well. Prose, poetry, song, painting, and sculpture all remain to reveal the soul of the community.

The historiography of the Hansabegan to grow from the infancy of modern historical research. A journal, Hansische Geschichtsblatter, began regular publication in 1871. Excepting the period of World War II, this journal continues to this day, Philippe Dollinger calls it the "...real backbone of Hanseatic historiography." Interest in Hanseatic scholarship was initially inspired by the search for identity that accompanied Bismark's unification of the Germany following the Franco-Prussian War. Certainly the timing of Hansische Geschichtsblatter's inception was not coincidental, early Hanseatic scholarship was tainted by the ideas of nationalism just as most other scholarship of the time. It has continued to change with the shifting intellectual fashions, moving through the economic theories of Marxism to the social histories of the mid-20th century.

The historiography of the Hansabegan to grow from the infancy of modern historical research. A journal, Hansische Geschichtsblatter, began regular publication in 1871. Excepting the period of World War II, this journal continues to this day, Philippe Dollinger calls it the "...real backbone of Hanseatic historiography." Interest in Hanseatic scholarship was initially inspired by the search for identity that accompanied Bismark's unification of the Germany following the Franco-Prussian War. Certainly the timing of Hansische Geschichtsblatter's inception was not coincidental, early Hanseatic scholarship was tainted by the ideas of nationalism just as most other scholarship of the time. It has continued to change with the shifting intellectual fashions, moving through the economic theories of Marxism to the social histories of the mid-20th century.

One constant in Hanseatic historiography has been the overwhelming number of German historians practicing in the field. With few exceptions, Philippe Dollinger being one of the most prominent, Hanseatic scholarship has been published in German, by Germans, and mostly for Germans. Those non-German scholars who do tackle the subject tend to choose narrow areas that impact upon their nation in some way. This tendency is understandable, but regrettable. The impact of the Hansa was international and had a great deal of influence on Western thought, it deserves a more through treatment by non-german scholars.

Archaeological scholarship is more international, the Bremen Cog was reassembled at the Deutsches Schiffahrts museum, but studies on her construction, characteristics, and other features have been undertaken by historians from a variety of other nationalities. The widespread use of the Cog during the Medieval period, ranging from northern Scandinavia to North Africa, inspires close studies of the vessel and the design relationships between the cog and later vessels.

History

The history of the Hansa can be divided into three distinct phases. The first is commonly called the Merchant's Hansa. This term covers a period from the founding of Lubeck in 1159 until the first general Hanseatic Diet in 1356. The second phase is called the Hansa of the Towns, running from 1356 until the closure of the Novogorod Kontor in 1494. The final phase can accurately be designated the decline of the Hansa, the actual date of dissolution usually being given as 1669, the year of the last Hanseatic Diet. These artificial divisions should not distract us from the essential continuity of Hanseatic history, they serve only as a means of organizing the information we have available into digestible servings.

The Merchant's Hansa was shaped by two distinct lines of evolution. The first was the founding of Lubeck and the rise of the urban centers in Northern Germany. Lubeck was founded in 1159 by Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony. He granted the town the iura civitatis Honestissima (Most Honorable Charter of Town Rights). Henry established Lubeck to encourage trade, he used the wealth thus gained in a revolt against the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick Barbarossa. Following the defeat of Henry the Lion in 1180, Frederick recognized the economic value of the town and confirmed the charter despite Lubeck's previous support for the Duke of Saxony. Frederick II made Lubeck an imperial city, this left the town with only one feudal overlord, the Emperor, and secured the town's independence.

Town law was the bedrock which allowed economic prosperity to grow in Lubeck and the other cities which followed its lead in gaining charters during this period. The motto "Town air is freedom" was actually a legal principle, a serf who managed to remain within town walls for one year was no longer a slave, but a town citizen. Citizens of a chartered town had the right to be tried under town laws, even in cases that were tried before feudal courts. The Hansa later extended this privilege to foreign shores as well, Hansa merchants were tried under the laws of the Hansa rather than the laws of the country where the case was heard. The influence of Lubeck grew through this process as many of the newly chartered towns simply followed the outline of Lubeck's charter. "Lubeck Law" thus became the legal standard throughout much of the Baltic and Northern Germany. The law was certainly biased in favor of the merchants at the expense of the craftsmen and laborers, but it was generally an improvement on feudal law for all walks of life.

The second thread in the development of the Merchant's Hansa was the establishment of the four Kontores. These were major trading posts established in the four main areas that German merchants traded within during the Hanseatic period: London, Novogorod, Bergen, and Bruges. Based on the idea of cooperation between merchants from the same lands, they provided a sense of community and familiarity for the merchants who were far from home. Three of the Kontores had their own compound which included living quarters, meeting halls, warehouses, and churches. The Peterhof in Novogorod and the German quarter in Bergen were both used to keep the merchants separate from the natives, the unity of the community was thus kept strong. This was not as strongly enforced at the London Steelyard, the Hanseatic merchants did not control as much of the export trade and there was a sizable native merchant class which resented their intrusion.

In Bruges there was no compound, the merchants acquired housing among the general populace. This was the largest and most economically important of the Kontores, the population spoke a language very similar to the Low German of the merchants and it was geographically closer. The result was that the Hansa had more problems with Bruges than any of the other Kontores. Disputes with Bruges led to a transfer of the Bruges Kontor to another town in Flanders four times. The importance of the town always brought the Kontor back, with assurances of privileges being granted to Hansa merchants.

It seems only natural that the cultural unity brought about by the spread of Lubeck Law and the common experiences abroad would lead to a more formal organization of the towns involved. The initial impetus was the opposition of the foreign governments and merchants to the privileges that the Hansa merchants enjoyed abroad. When these governments attempted to restrict the priviliges that the Hanseatic merchants enjoyed, the members of the Kontores naturally turned to their home towns for help. By this time many of the town leaders had made their fortunes in the Kontores, now their sons and nephews were continuing the same trade. The towns responded to these threats with economic embargoes and, in the case of Bruges, with transfer of the Kontor to a different location.

The economic clout of the German merchants allowed these tactics to succeed admirably. The first transfer of the Bruges Kontor in 1280 caused such a disruption in trade that Bruges was forced to grant new concessions above those initially stripped simply to return the Kontor in 1282. Norway became so dependent on the Prussian grain supply, which the shallow hulled Scandinavian vessels could not transport in sufficient quantities, that when the King tried to limit the influence of Hanseatic merchants in 1284, a blockade brought all of Norway to the brink of starvation. The negotiations which followed placed a stranglehold on the Norwegian economy, this lasted until the end of the Hanseatic period. The Hansa consistently held more influence in Norway then in any of the other nations they traded in.

As the concerns of the Kontores brought the towns into conflict, they began to desire better control over the actions of the Kontores. The various embargoes and blockades also required a greater degree of cooperation than the towns had previously mustered, these events thus led to the first Hanseatic Diet in 1356. The Hansa imposed more rigid membership requirements on the Kontores, requiring that their members be from a Hansa town. They also required that the aldermann or leader of the Kontor be a burgher from one of the Hansa towns. The Kontores were also restricted in the actions they could now take, in general being required to receive approval from the Hansa before taking any action that affected the whole.

The Hansa of the Towns was very successful, not only was it able to impose its will successfully through economic means, it also waged and won wars as a sovereign power. The most successful of these wars was against Denmark (1360-1369). After an initial Hanseatic fleet was destroyed by inept leadership, the towns banded together and collected a tax to pay for the war. While this was never completely enforced, it brought in sufficient revenues for the Hanseatic fleet to operate. In 1370, the Peace of Stralsund was concluded, the Hansa gained no new privileges within Denmark itself, rather the original privileges were restored and the freedom to sail the Kattegat straits was enforced by Hanseatic control of several key Danish fortifications. These were soon returned to Denmark, Hanseatic wars were not fought for territory, political motive or religious fervor, but rather for economic gain.

The Hansa did not fight land campaigns, its tactics consisted of coastal raids and piracy. This brought two gains, interruption of the enemy's trade and immediate gain for the Hansa. Used in conjunction with an embargo and blockade, this was a highly successful method of waging war. The Hansa used it to defeat Denmark in 1369, Denmark again in 1435, the Dutch in 1441, and England in 1474. As long as the majority of Hanseatic towns supported the conflict and paid their levies, the Hansa was victorious. The economic priorities of the towns insured that the wars were short, and that the members of the Hansa resumed trading with the enemy as soon as the war was over (actually before in many cases). One constant in Hanseatic peace terms was the payment of indemnities to the Hansa. This helped defray the costs of the war and was seen as legitimate by the Hansa, since the wars were fought over restrictions on privileges that the Hansa considered irrevocable.

In a sense, then the Hansa attempted to control the sea not through the traditional Mahanian sense of a superior naval force that physically prevents passage, but in an economic sense where the trade was blocked by high tariffs and restrictive laws at the destination. The Hansa could get around these same obstacles by virtue of the privileges they had secured. This in turn led to Hanseatic ships carrying the bulk of trade in the Baltic and North Seas. This meant that when the Hansa's privileges were threatened they could be defended by embargoes that could not be simply ignored. The ease with which early medieval ships could be converted between peaceable and militant uses meant that the huge Hanseatic merchant fleet was a source of military power as well as economic strength. At the technological level of the medieval world this method of sea control was much more practical and much less expensive than the Mahanian approach which would have required the Hanseatic ships to produce feats they were simply not able to perform, like remaining on station outside of a hostile port for even a short length of time.

The decline of the Hansa can be seen in closure of the Novogorod Kontor in 1494. Never known for great subtlety, Ivan III took a murder accusation and used it as an excuse to arrest 50 Hansa merchants and seized their goods valued at 96,000 marks. The Kontor never recovered from this, even when reopened 20 years later, the eastern branch of the Hansa was destroyed.

The destruction of the Kontor at Bruges was less dramatic but equally final. The gradual silting of the harbor began to reduce the city's importance as a commercial port. This led to a gradual shift of trade from Bruges to Antwerp. The Hanseatic merchants attempted to make this shift as well, but Antwerp was not as dependent on Hanseatic trade as Bruges had been and never started the cycle of privileges and embargoes which gave the Hansa so much of its power. Merchants from the Hansa towns traded in Antwerp in great numbers, but they did so on an equal footing with the merchants of other lands. When this trade led their towns into conflict with the rest of the Hansa, over embargoes usually, the towns had to ask themselves if the benefits of membership in the Hansa outweighed the disadvantages. This question was always present, Cologne especially often went its own way in defiance of Hansa policy, but began to really become critical when membership in the Hansa became an impediment to trade.

As the feudal states of north-western Europe became monarchies, they began to see the need for a strong native merchant class. The existence of privileged foreign merchants within the nation was a definite detriment to their formation and the monarchs began to take steps to eliminate them. Ivan III's closure of the Peterhof was only the first, Elizabeth I closed the London Steelyard in 1598. In Scandinavia, the Dutch began to offer an alternative to the Hanseatic fleets and this permitted Norway to come out from under the yoke of Hanseatic grain domination. The reformation placed further strains on the cooperation that was required for the Hansa to be effective. The military result of the Reformation, the Thirty Years War, placed strains on the economy of northern Germany that cracked the unity of the Hansa. The last Diet was held in 1669, but the alliance of Lubeck, Bremen, and Hamburg in 1630 spelled the actual end of the Hansa, as its most important cities abandoned it to form a smaller, more unified league.

Different Types of Cogs

Different Types of Cogs

The discovery of the Bremen Cog by Siegfried Fliedner in 1964 open up an entire new world for naval archaeologists. The recovery and reconstruction of this vessel allows a greater understanding of the capabilities of these vessels as well as establishing guidelines for the identification of future wrecks.

A cog was defined as a "...high boarded ship of clinker construction with straight stem and stern posts and one square rigged mast." by Paul Heinsius in 1956. This was enough to enable Fliedner to identify the Bremen Cog and bring to light an important characteristic of the design, twice-bent nails. These nails were driven through the planks and then twisted around twice so that they reentered the wood. This discovery allowed archaeologists to distinguish cog finds from longships, which were constructed with diamond shaped rivets, even when the hull did not survive.

There are four distinct hulltypes found in Northern Europe during this period, the Nordic clinker type, the cog type, the hulk type, and the punt type. Each of these styles has certain advantages and disadvantages. They all have excellent coastal handling qualities in common. The Nordic clinker type is best seen in the famous Gokstad ship. This vessel has often been hailed as an impressive sailing craft, beautiful and swift. In speed and handling, its design can hold its own with modern yachts, its Displacment-Length Ratio measures at 77.6, better than many modern racing yachts. This type of vessel was used by Scandinavian traders when they dominated the Baltic trade through the 10th and 11th centuries. Its freeboard and carrying capacity were both too low for the needs that came later, and it was almost completely supplanted in the Baltic by the Cog during the 12th century.

The cog was a far less graceful vessel, the Discplacement-Length Ratio of the Bremen Cog was computed as 51.6, much worse than that of the Gokstad ship. Her major advantage was in cargo capacity. A cog could carry up to 200 tons of cargo and required a smaller crew to sail. The relatively flat bottom made the Cog well suited for the same fjords the longships used, with deep channels and short shelving beaches. The Cog also enjoyed a military superiority over the longship. Lacking the development of of a ship killing ram, the standard tactic for the longship was boarding. The high sides of a Cog were excellent platforms for this sort of fighting. The development of the crossbow granted a further advantage to the relatively small crews of the cogs.

The most likely line of development of the cog flows not from the longship, as previously believed, but rather from Frisian boats. Many of the vessels that the cog descended from are still in use, one the "Kahn" has a distinctive steering mechanism. Instead of a rudder, it uses a "firrer." This is a simple board which is raised and lowered in the water like a leeboard. This causes the ship to twist into the wind as the lateral resistance changes. A medium position which changes with the speed and direction of the wind keeps the craft in a straight line. This "firrer" seem to appear on cogs seen in 13th century Lubeck seals, and combines with structural details of the Bremen cog to indicate a Frisian origin.

Bibliography

Christensen, Arne Emil. Viking Age Rigging, a Survey of Sources and Theories

The Archaeology of Medieval Ships and Harbors in Northern Europe. B.A.R. International Series 66, 1979.

Crumlin-Pedersen, Ole. Danish Cog Finds

Dollinger, Philippe. The German Hansa. Stanford Univ. Press. Stanford, California.1970.

Ellmers, Detlev. The Cog of Bremen and related boats.

Gillmer, Thomas. The Capability of the Single Square Rig-A Technical Assessment.

LLoyd, T.H. A Reconsideration of two Anglo-Hanseatic Treaties of the 15th Century. English Historical Review v102. 1987.

Mersden, Peter. Medieval Ships of London

Parker, Geoffrey. The Military Revolution. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge. 1988.

Pryor, John. Geography, Technology and War. Cambridge Univ. Press. Cambridge. 1988.

Reinders, Reinder. Medieval Ships: Recent finds in the Netherlands.

Smith, Roger. Vangaurd Of Empire. Oxford Univ. Press, New York. 1993.

Editor's Note:

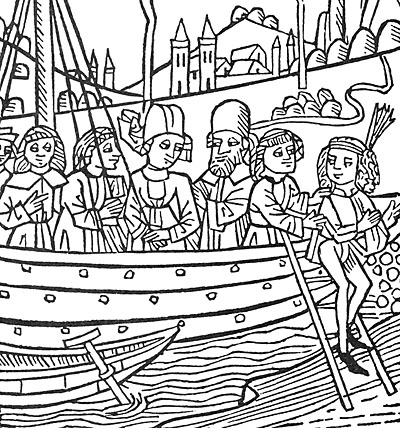

Paul submitted this excellent article to me quite some time ago, and I apologize for taking so long to print it. I also apologize if the images I used to accompany his story are NOT accurate portrayals of Hansa. I used Dover Publications, Inc.'s, "The Middle Ages" to give more of a FEEL for the period, rather than an accurate depiction of the ships and people Paul is describing. So, blame any inaccuracies on the editor rather than the author.)

Back to The Herald 63 Table of Contents

Back to The Herald List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by HMGS-GL.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com