In the last months of 1854 the gold fields of Ballarat in the colony of Victoria in Australia were in turmoil. Long seated grievances held by the thousands of gold diggers at Ballarat against a miner’s licence tax, the methods it was collected, and the refusal of the colonial government to consider allowing the diggers a vote or the right to own land, boiled over into armed rebellion. The insurgent diggers formed their own army and began drilling with firearms and homemade pikes. Alarmed by this show of armed defiance and fearing it presaged a “democratic revolution” the authorities reacted decisively and attacked he main encampment of the insurgent diggers, a stockade built on the Eureka gold lead, at dawn on Sunday the 3rd of December.

In the last months of 1854 the gold fields of Ballarat in the colony of Victoria in Australia were in turmoil. Long seated grievances held by the thousands of gold diggers at Ballarat against a miner’s licence tax, the methods it was collected, and the refusal of the colonial government to consider allowing the diggers a vote or the right to own land, boiled over into armed rebellion. The insurgent diggers formed their own army and began drilling with firearms and homemade pikes. Alarmed by this show of armed defiance and fearing it presaged a “democratic revolution” the authorities reacted decisively and attacked he main encampment of the insurgent diggers, a stockade built on the Eureka gold lead, at dawn on Sunday the 3rd of December.

The fight was brief, but hard fought. The 120-150 insurgents within the stockade gave a good account of themselves against the 276 soldiers and police sent against them. Defeat was however inevitable for the diggers, and after about twenty minutes the stockade had fallen to the military. More than forty diggers lay dead. There were eighteen military casualties, twelve being wounded and two being killed outright with four who would later die from their wounds, including two officers. One police trooper was wounded. In one swift stroke the insurgency was crushed but ironically for the colonial government the war was lost. Public reaction to what was seen as a heavy handed and unnecessarily brutal response by the government to the situation at Ballarat was overwhelming negative. The press turned on the government with a vengeance and great public meetings occurred at which the government was heatedly criticised. After a failed attempt to try and convict some of the participants of the rebellion for treason the government capitulated. Within a year of Eureka all of the political demands being made by the diggers would become law.

The insurgent army raised by the radical “Physical Force” faction of the Ballarat digger’s ‘Reform League’ movement consisted of about 1500 armed men, although numbers were never fixed or for that matter actually counted. For a variety of reasons only a fraction of those men were present at the stockade the morning it was attacked. The members of this army represented every class and nationality of digger at Ballarat.

One group that joined the rebellion on the day before the stockade was stormed were the Independent Californian Rangers Revolver Brigade. As the name implies this formation was composed mostly of “Californians” many of whom were native born Americans, and also quite a few who were known as “Whitewashed Yankees”, mostly Irishmen who had lived in the USA and been at the Californian gold fields during 1849 and the early 1850s. These men were well armed each having a Colt revolver and many also carrying large “Mexican” knives, as they were described by one observer. These would have been Bowie knives, a weapon favoured by American diggers. There were about 200 Californian Rangers who were “commanded” by James McGill, a 21 year old who claimed to have attended a military academy in the United States. The night before the stockade was stormed McGill and most of the Rangers as well as several hundred others of the best-armed insurgents left the stockade and moved south about ten miles to ambush an expected column of soldiers and capture their artillery guns. Unfortunately for the insurgents the report of the imminent arrival of these troops was a ruse, it would be another two days before they would reach Ballarat. Only 20-30 Rangers remained inside the stockade where they carried out sentry and picket duty.

When the attack occurred the Rangers were in the thick of it and noted by other diggers as running straight at the soldiers firing their revolvers. One Ranger, a man named Burnette, claimed to have fired the first shot that started what a Ranger comrade of his later described as “The Ballarat War”. Another, known as a “Captain”, impressed many with his energy even after being shot in the thigh.

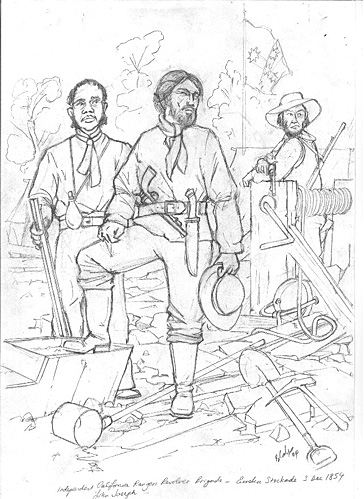

The illustration accompanying this article depicts typical Californian Rangers at Eureka. One leans on a mine windlass while the other stands with his foot up on a mining cradle used to sift the dirt. Scattered about them are various implements necessary for gold mining at the time. In the background is the Southern Cross flag of the insurgents.

The figure standing to the left represents John Joseph, an African American, digger who was captured during the fight for the stockade and later put on trial for treason. Despite the best efforts of the Attorney General to convict him the case failed and Joseph was acquitted. The rejoicing in the court at this result was so loud that two men were jailed for contempt as they were cheering too loudly.

The Independent California Rangers Revolver Brigade existed for about two days. Only a fraction of it ever saw action and after the fall of the stockade the rest quietly dispersed, its members mostly returning to mining for gold. Nevertheless the Rangers role at Eureka was not an insignificant one and therefore their contribution to the colonial history of Victoria and Australia deserves to be acknowledged. It is by modest memorials such as this that one hopes this may occur.

Back to The Heliograph # 147 Table of Contents

Back to The Heliograph List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Richard Brooks.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com