This year, 2004, marks the 150th anniversary of the uprising by gold miners on the diggings of Ballarat in Victoria that culminated in the brief but bloody storming of the Eureka Stockade by soldiers and police. A small affair by the standards of other military campaigns, nonetheless it was an event that had a dramatic impact upon political events in the Australian colonies of the day.

This year, 2004, marks the 150th anniversary of the uprising by gold miners on the diggings of Ballarat in Victoria that culminated in the brief but bloody storming of the Eureka Stockade by soldiers and police. A small affair by the standards of other military campaigns, nonetheless it was an event that had a dramatic impact upon political events in the Australian colonies of the day.

After Eureka the political landscape in the Australian Colonies changed forever. While there were other factors pushing the Australian Colonies along the path of more representative government at the time, the Eureka rebellion dramatically stamped the political reform process with an undeniably modern democratic character from which there could be no retreat.

In July 1851 rich deposits of gold were found in the Australian colony of Victoria. This led to an immediate and frenzied gold rush. Many workers and government officials abandoned their jobs and together with tens of thousands of gold seekers from elsewhere in Australia and around the world trekked to the gold fields to find their fortunes. Between 1851 and 1854 the population of Victoria grew from 77,345 to 236,798, whom 66,694 were on the gold-fields.

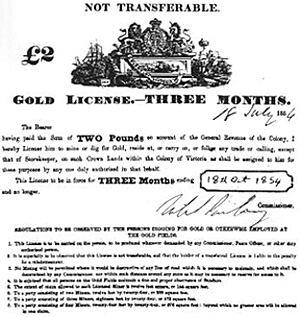

In an attempt to control the growing gold fever and raise some revenue to build the infrastructure necessary to service a booming population the Victorian authorities decreed a license fee of 30/- (30 Shillings) per month to search for gold. 30/- per month was more than the average man would earn in a month working. This fee was to be paid if gold was found or not and caused resentment amongst the Diggers, leading to the first examples of refusals to pay the license fees which were suppressed by the Police.

The Victorian government, dominated by the Crown appointed Governor whose tame Legislative council was the preserve of wealthy land-owners and crown appointees, decided to double the license fee to 3 Pounds per month. Massive protests at the Castlemaine and Bendigo diggings, forced the government to back down. However it was not in the nature of the colonial authorities to allow themselves to be cowed by the common people. Early in 1852 the Police begin raiding miner's camps, in what would become known as "Digger Hunts". Mounted Police, called “Joes” by the Diggers after the then Governor of Victoria Joseph Latrobe, conducted these hunts enthusiastically.

The Victorian government, dominated by the Crown appointed Governor whose tame Legislative council was the preserve of wealthy land-owners and crown appointees, decided to double the license fee to 3 Pounds per month. Massive protests at the Castlemaine and Bendigo diggings, forced the government to back down. However it was not in the nature of the colonial authorities to allow themselves to be cowed by the common people. Early in 1852 the Police begin raiding miner's camps, in what would become known as "Digger Hunts". Mounted Police, called “Joes” by the Diggers after the then Governor of Victoria Joseph Latrobe, conducted these hunts enthusiastically.

The fine for not having a Miner's License was 5 Pounds, an astronomical sum for a workingman at the time. Those apprehended were subject brutal treatment such as being chained to trees in the open to wait their trials, not a very pleasant experience in the hot Australian summers or freezing winters. Trials could be often delayed for weeks. Such humiliating treatment at the hands of the Police was bitterly resented by the self-reliant and independently minded Diggers, many of who had come to Australia to escape such arbitrary displays of coercive force by governments. Along with the government's laws the very nature of the Police force was at the root of the problem. Because most of the serving police had resigned and left for the gold fields and the lack of appeal for the job in an environment promising quick riches there had been a chronic shortage of recruits for the Police force.

The Victorian Government resorted to recruiting pardoned convicts or ex-convict overseers from Tasmania to serve as Constables (Troopers). Many of the police administrative were equally unsuitable people. Corruption amongst law enforcers was endemic. In contrast to the Troopers they commanded Police Officers were often young men from well to do British families, many with the aristocratic social attitudes of that class.

The Victorian Government resorted to recruiting pardoned convicts or ex-convict overseers from Tasmania to serve as Constables (Troopers). Many of the police administrative were equally unsuitable people. Corruption amongst law enforcers was endemic. In contrast to the Troopers they commanded Police Officers were often young men from well to do British families, many with the aristocratic social attitudes of that class.

Agitation

It was in 1853 that serious agitation for significant political change began. The initial protests by tens of thousands of Diggers resulted in petitions for representative government and a repeal or modification to the license laws. Typically the Victorian colonial government ignored the petitions and did nothing. It was to be on the Ballarat diggings, where the enforcement of the mining laws had been particularly harsh and authoritarian that violent opposition to the Mining Laws would occur.

In June 1854 Sir Charles Hotham, the new Governor of Victoria, announced that "Digger Hunts" would occur twice a week. This was against the direct advice of his Commissioner of Police. Hotham's "Digger Hunts" met with bitter resentment from the miners especially on the Ballarat diggings. The situation was becoming very dangerous and waiting for a reason to explode. This reason occurred on 6 October 1854 with the murder of James Scobie.

James Scobie was a former sailor who had come to the gold fields to seek his fortune. Following a late night altercation at the Eureka Hotel he was murdered. The circumstances of his murder were murky but it was accepted by all that the deed had been done by James Bentley the proprietor of the Hotel. Bentley was arrested but acquitted despite all the evidence pointing to his guilt. The Diggers reacted with fury.

On 17 October 1854 a crowd of 10,000 Diggers gathered outside the Eureka hotel. There was no obvious sign of violence but then a young lad threw a stone and smashed a lamp on the hotel. A large number of Diggers then went wild and surged into the building destroying everything. The hotel and its adjoining bowling alley was then burned to the ground. Desperate to find scapegoats and set and example the government responded by arresting three men and sentencing them to prison. It did not bother the authorities that the three men they had imprisoned had had nothing to do with the attack on the Hotel. Frightened by the palpable fury of the Diggers at these events the authorities for once took notice of the mood on the gold fields and responded by sending Bentley and his accomplices to Melbourne where they were retried and convicted of manslaughter. However, by this time the miners were so angry with the government that it just didn't matter.

Late in 1853 the Diggers at Ballarat had formed "The Ballarat Reform League". On 27 November 1854, a delegation to the Governor from the Reform League demanded that the three men who had been imprisoned following the burning of the Eureka Hotel be released. Governor Hotham objected to the miner's "demanding" anything from him and refused to release the prisoners. Hotham then ordered military reinforcements to Ballarat, a decision that was to have tragic consequences.

Attack

When the soldiers marched into the Ballarat diggings they were pelted with stones and abused. A drummer boy was shot in the thigh and by some reports later died, although this is disputed in some sources. Mounted police were called in to restore order. That night the Diggers kept big bonfires burning, shouted and fired shots into the air. The situation was rapidly getting out of control.

On 29 November 1854 the Southern Cross Flag, bearing a stylized white southern cross on a dark blue field, was raised on Bakery Hill. 12,000 Diggers gathered beneath the Southern Cross in full view of the army camp to hear that Governor Hotham had refused to release the three arrested miners. In response they piled up their licenses and burnt them.

On 29 November 1854 the Southern Cross Flag, bearing a stylized white southern cross on a dark blue field, was raised on Bakery Hill. 12,000 Diggers gathered beneath the Southern Cross in full view of the army camp to hear that Governor Hotham had refused to release the three arrested miners. In response they piled up their licenses and burnt them.

Incredulously given the circumstances Commissioner Robert Rede, who commanded the Police on the Ballarat gold fields, ordered another "Digger Hunt" assisted by the army to occur on 30 November. The day of Rede's "Digger Hunt" was a very hot and dusty. During the hunt shots were fired at Diggers who tried to run away and eight were arrested. This only caused large numbers the Diggers to gather and they began throwing rocks at the police and soldiers. Rede read the Riot Act to the crowd and the soldiers fired over their heads but this had no effect. Frustrated Rede and his men then withdrew to their camp.

Having got a taste of how the authorities intended to deal with the grievances the Diggers held another meeting was beneath the Southern Cross flag on bakery Hill. During this meeting Peter Lalor, a member of the Ballarat Reform League was elected as leader. Lalor addressed the crowd and proposed an oath be taken.

He ordered all those who did not want to take the oath to leave the crowd. When those men had gone he knelt down and took of his hat, the 500 remaining miners, many armed, did the same. Lalor then pointed at the flag and pronounced the oath, "We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other, and fight to defend our rights and liberties." All the diggers present replied with "Amen". They then paraded out of their meeting in military formations and bearing arms as a band played "La Marseillaise". That evening a delegation from the Diggers demanded that Rede release the eight men arrested that day. Rede rejected the delegation out of hand.

Later that evening he voiced his opinion that the Diggers were bent upon "democratic revolution". In the next three days a site was selected and cleared and a rough stockade using a barricade of slabs was constructed. This became known as the Eureka Stockade after the diggings where it was built. Miners went out and began collecting food and guns to add to their existing stocks of pikes and firearms.

Frightened by events, Commissioner Rede responded to a number of Digger's deputations with some conciliatory responses. This lead to some of the Diggers leaving the stockade and losing interest in fighting the police. However Rede's conciliatory responses were nothing more than a sham. On 2 December, the same day the stockade was completed, Rede revealed his true intentions when he wrote of how he was convinced the moment had come to "...crush the democratic agitation at one blow". Rede's actions were influenced by rumors that 1000 armed Diggers were marching to Ballarat from the diggings at Creswick, about one day distant. Subsequently he ordered that a military and police assault against the stockade be conducted the following morning.

During the night of 2 December, which was a Saturday, many of the Eureka Diggers had drifted away from the Stockade leaving only 130 men there. No one amongst the Diggers expected the authorities to attack the stockade on the Sunday, which was the Sabbath and was always strictly respected in the diggings, but they were wrong.

Attack

Shortly after 4 a.m. on 3 December two companies of the 12th and one company of the 40th Foot assaulted the stockade. 76 dismounted and 100 mounted Police remained in reserve, waiting for their chance to intervene pr cut down any fugitives. Advancing out of the early morning light the soldiers were spotted by one of the Diggers whose shot rallied the Diggers several of who began to fire at the advancing soldiers. It was at this time that Captain Wise, the Officer in command of the assault was shot through both thighs and fell. Wise would later die from his wounds. It was established after the event that John Joseph, an African American Digger, fired the shot that felled Wise. A volley from the soldiers cleared the defenders from the stockade's rough palisade and the troops surged forward with the bayonet.

Total pandemonium reigned within the stockade as many Diggers tried to flee and others stood their ground. As a group of about six soldiers crested the palisade they were met by a contingent of Diggers armed with pikes and in the ensuing melee several Redcoats fell wounded with one killed outright by a stab to the chest. The courage of the pike armed Diggers however could not delay the inevitable and they were quickly overwhelmed and either killed, wounded or captured by the soldiers as they surged into the stockade. Those Diggers who had firearms tried to resist but they too were killed, wounded or disarmed. The Police, who had been standing back then intervened, rushing triumphantly into the stockade. The Southern Cross flag was ripped down and many of the wounded Diggers lying scattered about the stockade were bayoneted, stabbed and bashed by the vengeful Constables. 34 miners died and 5 soldiers, including Wise, were killed. 12 Soldiers were wounded. Peter Lalor had been badly wounded in the arm was hidden under a woodpile from which he was recovered during the night by friends, who would arrange for the amputation of his arm that same night.

The attackers took 120 prisoners, some of whom had only been passing by and had nothing to do with the fighting. Many wounded Diggers were hidden by their friends and died later. That night the Police rampaged through the Ballarat diggings firing indiscriminately into any tent that showed a light. The full death toll of the Eureka uprising will never be known.

Rewards were posted for all the leaders of the Eureka 'rebellion' but many of them, including Lalor, were hidden by sympathizers and eluded capture. Eventually though 13 men were put on trial for Treason. The Government attempted to portray the uprising as a rebellion by Irish troublemakers. In fact of those for whom the nationality was known there were 19 nationalities present amongst the Diggers at Eureka including 38 Irish, 16 English, 9 Americans, 4 native born Australians as well as men from many other lands such as Italy, Germany, Canada and even the West Indies. The Governor's attempts to stack the juries and influence the judge all failed and eventually all the accused were acquitted. Not one of the 180 people empanelled for jury service would convict them. There was general

Two of the most important political aspirations of the Diggers were the desire for representation in government and the right to own land, both of these things had been denied to them by the Government of Victoria. After Eureka though things changed. Within one year of the rebellion Victoria had:

- Reformed the administration of the gold fields.

- Granted the vote to all adult men in the colony regardless of property.

- Allowed the sale of crown land to anyone who could pay for the land.

- Paid a salary to members of Parliament thus allowing ordinary people to serve as members.

- NSW followed Victoria in 1856

The events that occurred at the Eureka Stockade represent a most significant milestone in the development of truly democratic government in Australia. The vibrant modern democracy Australia now enjoys exist in no small part because of the stand made by the Diggers at Eureka in December 1854 against arbitrary and corrupt authority.

Map

Back to The Heliograph # 145 Table of Contents

Back to The Heliograph List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Richard Brooks.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com