Like many others I once believed the Battle of Omdurman was an easy victory for the Kitchener’s Anglo-Egyptian army. I had heard the popular version of events, that of a foregone conclusion of modern weaponry against spears and swords.

Like many others I once believed the Battle of Omdurman was an easy victory for the Kitchener’s Anglo-Egyptian army. I had heard the popular version of events, that of a foregone conclusion of modern weaponry against spears and swords.

Some years ago I was enlightened by Churcill’s “The River War”. His account of the actions of McDonald’s Sudanese Brigade was exhilarating stuff indeed. More recently I acquired Phillip Ziegler’s excellent book, “Omdurman”, and learned of the largely unsung part played by the Egyptian Camel Corps and Cavalry in the Kerreri Hills.

Overview

The bulk of Kitchener’s army formed a semi-circular defensive position with its back to the Nile. Their front was protected in part by a thorn bush ‘zareeba’ barricade and by trenches. To their right, the Kerreri Hills were held by the Egyptian cavalry, Egyptian Camel Corps and Horse Artillery under Colonel Broadwood.

Terrain

The Kerreri Hills rose to a height of 250 feet and dominated the plain in front of Kitchener’s army. Their slopes were rocky and rough, hard going for both horses and camels. The going was over sharp stones, thorns and holes.

The first ridge faced South Eeast, behind was a valley perhaps 1000 yards wide, rising to a further rocky ridge of hills. Behind this lay the Nile and the village of Kerreri.

Both ridges were about 1000yards from the Nile.

Deployment

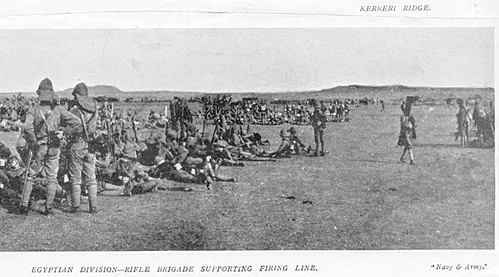

Churchill gives the position of the Egyptian force as lining the Southern-most ridge. The dismounted Camel Corps held the right, nearest the desert. Nine squadrons of dismounted cavalry were in the centre, with Horse Artillery on the left nearest the Nile. A cavalry reserve as well as the cavalry horses and camels were in the dip between the ridges.

6.45a.m., the Dervish attack.

The main Dervish force advanced to attack the British line by the Nile, but a separate massive force surged towards Broadwood’s troops lining the Kerreri Hills. Broadwood’s small command was suddenly faced by a huge attacking army of at least 15,000 men, commanded by Sheikh el Din and a further 5,500 under Ali Wad Helu.

Kitchener sent word for Broadwood’s force to withdraw to the zareeba and join the main British force. Broadwood considered this a risky move at best. Even if he could do so, his withdrawal would bring the massive pursuing wing of the Dervish army down upon the weakest link in Kitchener’s line, the Egyptian battalions. He was by no means certain the Egyptian infantry would stand in the face of such an attack. If they failed the entire flank of the army could collapse.

Instead he ordered a fighting withdrawal Northwards, hoping to draw the Dervishes in front of him away from Kitchener’s main force. He sent word to Kitchener that it was too late to rejoin.

The fighting withdrawal

“We opened fire, but failed to check their advance.”

- --Captain Green-Wilkinson, Rifle Brigade. Attached to the Camel Corps

The Dervishes closed quickly. By the time the defenders had quit their ridge and reached their camels below, their enemies had already swarmed over the positions they had just abandoned. The action now became a race, and he price of delay was death. The laden camels could manage perhaps six miles an hour over the treacherous, rocky ground, the Dervishes came on at almost eight miles an hour.

The Horse Artillery delayed their departure too long. One horse was shot, and while the crew tried to cut it free another gun crew galloped up to assist. Their 7 ponder Krupp gun became entangled in the wreckage and capsized. With the Dervishes now within a hundred yards and closing fast both guns had to be abandoned. It was the narrowest of escapes. Hanging from a friendly stirrup or doubled up on horseback, the gun crews fled in the nick of time, their triumphant enemies claimed the abandoned guns.

As the artillery and Camel Corps made their escape the cavalry harried their enemies wherever they could.

The squadrons in contact with the Dervishes were commanded by Douglas Haig, and with great coolness he and his men did what they could to impede and harass the massive force bearing down on them. They kept always within a few hundred yards of the onrushing army, firing, retiring and dismounting to fire again. They stung their opponents but could not halt such overwhelming numbers, it was enough to keep heir attention and lead them on towards the North, away from Kitchener’s army and the fleeing Camel Corps. It was finely done, and finely judged. They baited their opponents with their own lives.

By now the Camel Corps had reached the open plain and fled towards the Nile and the shelter of the main army. Enough of the Dervish force pursued them still, more than enough to massacre them if they could catch them. The Camel Corps still had 2000 yards of open ground between them and safety, and it was clear they could not make it.

Broadwood had crossed the valley between the two lines of hills and now held the bulk of his cavalry on the forward slope of the second ridge. He was faced with an impossible choice. He must either stand by while the Camel Corps was destroyed or else charge his cavalry across difficult ground into impossible odds in a desperate, perhaps suicidal rescue attempt.

Into this crisis steamed their deliverer, the gunboat Melik. Kitchener had signalled to his gun boats on the Nile, and even as the Camel Corps was cut off and about to be surrounded, the Melik arrived with guns blazing. She carried two Nordenfeldt machine guns, a quick-firing 12 pounder, a howitzer and two maxim guns, and she poured a storm of fire into the masses of charging Dervishes.

In an instant the situation changed. The Dervishes could not stand in the face of such firepower and had no answer to it. As a second gunboat, the Abu Klea neared the scene and began firing a Krupp gun from the range of a mile, the Dervishes gave up the chase and moved away.

The Dervish force was still intact and very dangerous, but now they turned their attention back to Broadwood’s Egyptian cavalry. The emirs were unable to hold them back, and they surged away to the North after the irritating, infuriating little bands of horsemen.

“The Horse Artillery Battery, in perfect order, stopped and fired, then retired, then stopped and fired again.”

- --Major Newcombe, commanding the gunboat Abu Klea

This time the artillery fared better, and likewise the cavalry fired volleys before mounting and falling back in turn. Major Mahon led one squadron in a counter charge and saw off a band of Sheikh el Din’s cavalry.

“The cavalry, intensely relieved by the escape of the Camel Corps, played with their powerful antagonist, as the banderillo teases the bull”

- --Winston S. Churchill, ‘The River War’

It was a mobile battle, and Broadwood’s force gradually drew many thousands of Dervishes several miles away Northwards. They could not now threaten Kitchener’s army by the Nile. The cavalry eventually rejoined the main army, moving South along the Nile covered by the gunboats. By 8.30 in the morning this phase of the Battle of Omdurman was complete.

Gaming the action

The action around Kerreri Hills is loaded with possibilities for the gamer. Some will want to stage a refight as accurately as possible, and this would make an exciting and unusual spectacle. But there are other options. The incidents described will doubtless suggest many variants to the dedicated colonial gamer.

Actions involving a small, mounted force pitted against a far stronger one on foot can be set in many lands and eras. The crucial factor is speed. As we have seen, eye witnesses estimated the speed of the Camel Corps at six miles and hour over rough terrain, and that of their pursuers at eight miles per hour. This gives us something to work with.

The rocky terrain would also cause problems for cavalry and horse artillery. Then there is the problem of rescuing casualties in the face of a rapid enemy advance. (The Egyptians were under fire from the enemy mass throughout the action.) The fact that two guns had to be abandoned gives an indication of the nearness of the thing at Kerreri Hills.

Our local gaming group uses “The Sword and The Flame” rules, and the variable move distance according to die rolls works well in such situations. While the mounted troops have the edge in speed, the advantage falls away due to rough terrain deductions and the increased speed if Dervishes charge. Add to this the fact that the Dervish will cross rough terrain without movement penalty and suddenly we have a foot race on our hands.

Artillery has the option of either moving, or moving a reduced distance and firing.

It will take a cool and brave Anglo-Egyptian player to toy with his enemy as Broadwood and his men did. As long as this element of risk is present in the game the players should have an exciting time of it. And you may get to use a gunboat!

References and suggested reading:

Churchill, Winston S. The River War Prion Books Limited, 1997

A classic read by one who was there. Loaded with drama and detail for the gamer.

Neillands, Robin The Dervish Wars John Murray (Publishers) Ltd., 1996

Covers both the Gordon and Kitchener eras, this edition includes some amazing photographs taken at Omdurman.

Ziegler, Philip Omdurman

Collins 1973

A very detailed account of the whole campaign as well at the great battle. Highly recommended.

Finally, thanks to Old Comrades, Leith for the loan of his “River War” and Don Featherstone for his inspirational collection of prints and maps.

Back to The Heliograph # 134 Table of Contents

Back to The Heliograph List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Richard Brooks.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com