Following the new of the death of General Godon at Khartoum in 1885, a storm of loyal indignation swept the the Bristish Empire. In the young colonies of Australia, military forces were raised to be sent to the Sudan to assist Britain in avenging Gordon.

Australia was not yet a nation, still consisting of separate colonies. Of these colonies, New South Wales made the following offer in a cable to London, "This Government offers to Her Majesty's Government two batteries of our permenant Field Artillery, with ten sixteen-pound guns, properly horsed: also an effective and disciplined battalion of infantry, five hundred strong. Can undertake to land Force at Suakim within thirty days of embarkation. Reply at once."

Four times as many men applied to go as were needed for the force. Imperial military spirit was running high in the colony.

The military experience of the men was mixed. Private Robert Hunter wrote "some of our men wear the Crimean Madal and Turkish and Indian Mutiny Medals, some the Afghan Medal while other wears the Ashantee and Zulu Medals. Some of our men also had just left the British Army and was present in Egypt during the late campaign in 1882-3. Taking the whole Contingent into consideration they look a motly crowd. Some never handled a Rifle before while othres were fellows who niver was 50 miles from home in their life before."

The selection process continued throughout training, as fresh volunteers arrived, those already enrolled were still liable to be rejected in favor of a fitter or more suitable candidate.

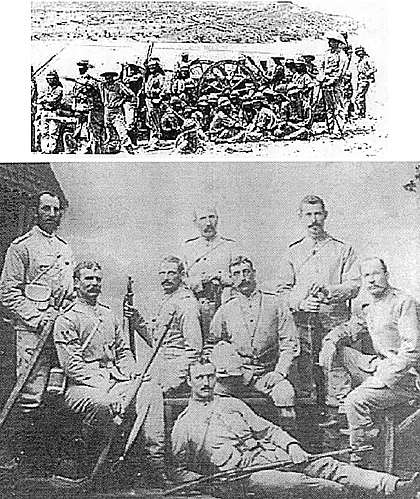

The contingent arrived at Suakin aboard the Iberia on the 29th March, and marched through the town in their scarlet jackets. They soon traded these for more practical khaki uniforms from London. White helmets and belts were stained with tea, coffee and tobacco juice. Goggles were issued, along with puggarees, neck flaps and spine pads. The continget was paraded with the Scots, Grenadier and Coldstrean Guards under the command of Major-general Fremantle.

The Australians had been at sea at the time of the battles of Hasheen and McNeill's Zareba. General Graham had awaited their arrival before leading a new attack. The combined force advanced to Tamai in hollow square, with Coldstream guards making up the front face, Sikhs the rear and New South Wales infantry with the Imperial regiments along each side. The Australalian artillery were left at Suakin. At McNeil's Zareba the troops breakfasted among the dead of the battle there eleven days before. The march was continued through 'rough and tough country', and great heat. At dusk a zareba was constructed, the only enemy to be seen all day were sighted from observers in the first balloon used by the British army.

During the night there was some sniping from enemy who crept up to the camp. The British 'replied with a few volleys and a couple of shells which quieted the enemy'. The British force suffered three fatalities, including one from friendly fire.

The advance towards Tamai resumed in the morning. The British force marched through the deserted village and encountered the enemy in the hills beyond. "Bengal Lancers rode to engage them, field guns got their range, and as the square lumbered through the dust across hilly ground, men in the front line fired volleys."

The Australians, now in the rear face of the square, suffered three men wounded. The Australians assisted in the firing of the village of Tamai and the whole force returned to McNeill's Zareba "after a gruelling day." Sporadic sniping continued during the night. On return to Suakin the Australians were ordered to a redoubt built to protect work on the railway.

General Graham wrote that the Australians 'bore themselves admirably', and showed a 'soldier-like spirit and endurance', and visited their camp to pay his compliments.

The Australians then began work on the railway, cutting their way through the prickly scrub and working in pairs. One man stood guard with his rifle while the other wielded the axe. Each night the troops camped within a zareba.

On the 18th April the contingent joined a reconnaissance in force from Handoub to Debberet. The march of 14 miles through very rugged terrain took nine hours but no enemy were seen. They moved further along the railway on 24th April but apart from the usual sniping there was no contact with the enemy. Osman Digna did not seem anxious for another battle. On 27 April the men were asked if they would volunteer to serve in India to counter the perceived threat from Russia. The majority of the Artillery, Regulars, did so, but the opposite was true of the infantry. The officers felt that, if ordered to India to oppose the Russian threat, the men would do their duty, but given a choice most preferred to return home. Back in Australia fears of a possible Russian invasion forced the politicians hand. As most British forces abandoned the campaign the Australians would sail for home.

Fifty Australians volunteered for the Camel Corps and went on reconnaissance with it to Takdul on 6th May. Fire was exchanged with parties of the enemy but the only real action was seen by two correspondents, Lambie of the Herald and Melvin of the Melbourne Daily Telegraph and the Bulletin, who shot and galloped their way out of a close encounter with enemy camel riders, Lambie being wounded in the skirmish.

On 15th May the Australians returned to McNeill's Zareba to bury the dead from the battle in March.

The New South Wales Artillery Battery saw even less action than their comrades, being based at the headquarters camp at Suakin then posted to Handoub. There they drilled. General Graham considered the battery "fairly efficient considering the many difficulties it had to contend with." They were withdrawn from Handoub on 15th May to join the rest of the contingent at Suakin.

In his final review the Commander-in-chief Lord Wolseley spoke well of the Australian's performance, "Australia, putting such a fine body of troops in the field, is a warning to any quarrelsome nation that they will have to fight not only Great Britain and Ireland, but also England's most distant colonies."

The next day Sir Gerald Graham also congratulated the men, and stressed the good discipline of the Colonial troops in his final dispatch to the war office. The Queen sent a message, expressing her satisfaction that her colonial forces had served side by side with British troops in the field.

The contingents horses were spared another voyage, being gifted to Her Majesty's government for the Royal Artillery. In return British made a present of the field guns supplied to the New South Wales Artillery. The troops embarked at Suakin on the 17th of May for the voyage to Australia. Losses for the campaign had been relatively light. Two men died aboard the hospital ship Ganges at Suakin, another of disease as the contingent reached Australia.

Gaming Notes

Though the contingent saw little real action, they were present and should be represented in a historical order of battle. They also make a colorful unit for those who like to play history's "might have beens".

Classifying the troops quality also requires some thought. Though never severely tested in battle they were reported to be steady under fire and well disciplined. They were also good at hard marching and stood the difficult conditions well. It also speaks well of the British assesment of them that they were brigaded with the Guards. Perhaps this was done for political reasons. But would the British risk exposing their best troops by brigading them with risky material?

Another factor is the high proportion of experienced soldiers in the infantry, drawn from many hard fought campaigns thrroughout the Empire. Perhaps if the contingent is to have any advantage over their British allies it may be they were more used to hot, dry conditions. If the gamers rules allow for a wide range of troop classes some tinkering is possible. Should they be rated as highly as the best British regulars? Perhaps steady but inexperienced? The choice is yours.

The artillery never seemed to be regarded as highly by the British. They were kept in the rear and constantly drilled. Conversely they were the only regulars with the contingent.

Perhaps if the contingent is to have any advantage over their British allies it may be they were more used to hot, dry conditions. If the gamers rules allow for a wide range of troop classes some tinkering is possible. Should they be rated as highly as the best British regulars? Perhaps steady but inexperienced? The choice is yours.

Miniatures

The idea of gaming a British square on the march through the desert, taking a tethered observation ballon along with it, is an attractive one.the Guards I'm currently unaware of any specific figures for the New South Wales contingent, but as they were quickly issued with British uniforms and equipment this should not present any great problems. If you feel you must raise figures that look the part, I suggest the addition of milliput neck cloths and curtains, painted on sand goggles and any other local addaptations to the hot dry climate you can think of.

Sources

Ingliss, K.S. "The Rehearsal", Kevin Weldon & Associates, McMahons Point. 1985

Sutton, R. "Soldiers of the Queen, War in the Soudan", New South Wales Military Historical Society, Sydney.1985

Australian Artillery and Infantry

Back to The Heliograph #118 Table of Contents

Back to The Heliograph List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by Richard Brooks.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com