Marketing: Specifically, Packaging

The Word has finally come to the Wargame Industry. And it has come with a big bang!

Several years ago it was not too uncommon to see new companies bring out games that Shopping Bag Ladies would reject. The scenario was that a couple of fellows had some good ideas for a game. They pooled their resources, whipped up a nice system on a good subject (or a mediocre system on an obscure subject), ran to their friendly printer, slammed the thing together, stole some brown bags from the local 7-11, and Voila! there it was ready for shipping. The "important" thing was that they (thought they) had a good game. The practical thing was that no one ever bought it.

Now almost no one spares the expense when it comes to the graphic end of the game. The Era of Packaging has arrived, and it's all a result of an increasing awareness in what is ubiquitously called Marketing. Very generally, it's not so important what you have as how you sell it.

The new companies, like OSG and, especially, Yaquinto, have jumped on the bandwagon with nary a look backward. Even at SPI, where marketing is still in the Neolithic Age, the awareness of packaging has grown to the point where they are even going outside the company to do some covers. All this may sound ultra-cynical, and in one sense, perhaps, it is. These companies, however, are in the business to make money. They are not, despite the deluded ravings of some of our vociferous letter-writers, here for the benefit of the gaming public; they are here to Make the Buck. And if they want to make good games, first they have to make good money. (Of course, what eventually happens is that making good games fades into limbo and The Big Buck starts to chew the scenery like crazy, but that's a management problem ... ).

In order to make that money these companies want you to pull their product off the shelf, and, given the number of companies out there scrambling for dollars, this can be a tough battle. So the boxes are now fourcolor process and the titles more emotional, more gut-level.

And the product itself -- the actual pieces of the game (not the game, per se) -- has also benefitted from this revolution. The old two-color, hand-drawn maps have been replaced by multi-colored phantasmagoric exercises, and the counters look like giant boxes of Crayolas. If the game looks good, the emotional reaction is that it must be good, and if the publisher can get you to start actually playing the game with this feeling, he's two points ahead. (All of this is borne out by studying trends in the various feedback surveys conducted by companies, especially concerning correlations between ultragraphic games and their ratings.)

Avalon Hill: War and Peace

The undisputed Wargaming Marketeer is Avalon Hill. Almost all of their ex pertise is in marketing, where they feel they know what it takes to sell a game; the worth of their games - which are, in the long view, surely no worse or no better than any others - is virtually secondary to their selling of these games.

The publication of the Mark McLaughlin/Frank Davis War and Peace (AH's game on the Napoleonic Era) thus comes as somewhat of a surprise, given AH's track record and perception of its buying public, because War and Peace, like the title itself, is simply one giant paradox in terms of marketing and designing for public consumption.

The most important area of marketing - an area that admittedly assumes less significance in terms of playability - is the appearance of the game, and with War and Peace it is hard to believe that Messrs. Greenwood and Shaw would ever let this visual disaster out the back - no less the front - door. The box itself is very nice: four color process reproductions of 19th Century paintings always look good, and this one is especially appealing (although not as attractive as the ones that OSG has been using on the same subject).

Taste and ability, however, take an immediate sabbatical upon opening that box. You have the standard AH rules booklet, perhaps a bit starker than previous efforts, but certainly easy to read and functional, as well as some nice charts that are pretty useful and only a bit cluttered. The major problems are the map and counters.

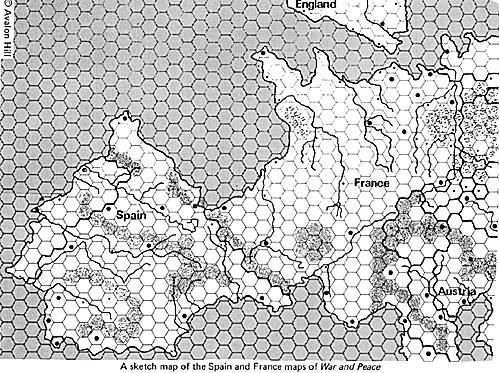

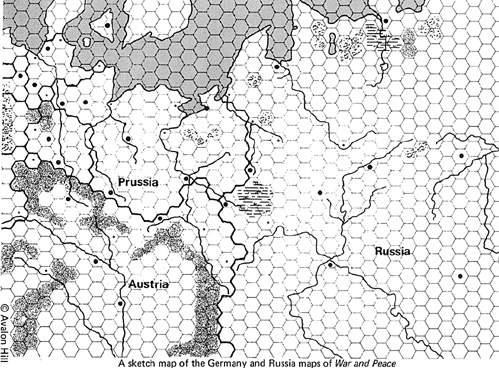

The map bears a startling resemblance in style to Russian Campaign, which may be all right for WWII but is definitely not for a nineteenth century strategic game covering a multitude of countries, duchies, and states. The map itself is drab if neat, and it is divided into four separate, mounted (and in my copy somewhat warped) sections covering Spain to mid-Russia.

Each map is 11" by 17", and almost all the scenarios take place on about one and a half of these maps. For a game of this scope that's not much of a playing area; in terms of graphics this produces even more problems.

Firstly, in several sections of the map there are a plethora of little countries and states. Given the small map surface they are so crowded together that they are impossible to read when covered by units. And this leads to a second, and major, question. Given the above problem plus the era being simulated, why was not a map produced with some color, some visual excitement, some way of telling "A" from "B".

After all, this is the Napoleonic Era: troops strutted into battle wearing brilliant, if somewhat non-functional, uniforms, and at least a part of the romance of the era is the swirl and panache of this very mixture of colors. Nowhere on the map is this evident, nowhere does one get the striking visual impact of a Kingmaker, a Diplomacy, or even A Mighty Fortress - games all helped immeasurably by their graphics.

To those who say, ". . . well, what difference or effect does this have on the game itself; you can still play it as well without color as with it, hmmm?", I insist that it is more fun, more exciting, and more evocative when the game has some zip, some empathy with its subject, than when it just lies there like cold spaghetti.

All this would, perhaps, be ephemeral if it weren't for the counters. Quite simply, they are the worst I have seen in the hobby in ten years. They are not only downright ugly, they are relatively functionless and readable only if you have an electron microscope or use the bottoms of cola bottles as contact lenses. I would expect better from a Casciano game (which, believe me, is saying a lot). I don't know who designed these or worse, who okayed them, but both (or all) should be considered for simulation euthanasia or, at the least, be locked in an airless garret with past volumes from the Famous Artists' School.

The colors are garish and primitive, the printing is miniscule and illegible (it is virtually impossible to tell the "C" for Cossack from the "G" for Guards on the Russian units), and the symbology non-informative. Amateurish would be a compliment, burning would be a relief.

Game Play

OK, so the map is bland and the counters are turkeys. Never mind that, how's the game? Generally speaking, it is a paradox. I feel that the problem is in that trying to cover both ends of the gaming spectrum - the player versus the historian/buff - the designer and the developer will please neither.

The game is pretty simple, and old war-horses should have little trouble with most of the rules. There are nine scenarios covering the individual campaigns, such as Spain, Waterloo, Austerlitz, Russia, etc. These use, usually, two of the four maps and a minimal number of optional rules. Playing time runs from an hour (Austerlitz) to a long run (The Peninsula War), and most scenarios are geared for two players. The massive campaign scenario utilizes from two to a bunch and probably takes about 100 hours to complete.

The basic system is simple, yet effective. Movement is fairly commonplace, except to note that because of the map size movement rates are fairly slow. This is augmented by the use of Forced Marching. Virtually all movement is through Leaders, who also figure greatly in the combat system. Supply uses the time-honored "trace three hexes back to supply source" idea, and attrition occurs without supply. Combat is handled simply but nicely, with the maximum odds available being 2:1! Leadership and morale are very important, as is the rule covering concentration of forces and the ability to add previously uncommitted units.

The latter is one of the few nice Napoleonic touches available. Combat results are in losses of strength points, dependent upon the total strength of the force. There is a rule covering committing the French Imperial Guard that sounds nice but allows the Guard to act as a sort of deus ex machina; it needs toning down.

There is a basic rule on the many possible alliances, and although this rule is fairly opaque, all comes relatively clear in the individual scenarios. (in fairly involved games alliance rules can become quite complex and a bit of a drag.) There are also many special rules throughout each of the scenarios, and the compaign game has a host of them, including naval warfare, creation of minor states, prisoner exchanges, and even exiling Napoleon! The basic system rules are fairly short, covering about 7+ pages, and the emphasis is on playability.

In terms of just that, playing the game can be good fun. Some of the scenarios, such as Austerlitz, are a bit too quick (one mistake and you're gone), but others, like the Peninsula War), offer many opportunites for bluff and strategy. For example, in the latter, the British/Spanish player has to try constantly to pull the French out of position grabbing a city here, a position there, trying to get the French player to extend his supply just a hex or two too far. With the constant (if somewhat arbitrary) shuffling of reinforcements and replacements arriving and leaving, both players are constantly on the lookout for the quick opportunity, and play evolves around positioning, rather than decisive battles.

To this extent this scenario manages to capture the flavor of that difficult campaign. On the other hand, there is still a curiously empty and detached feeling about all of this. There is little player identification with what is going on (and, to be sure, the role- playing aspect of pre-20th century games should not be underestimated in its effect on playability and pure enjoyment) and all of it is happening over such a small area (almost all action takes place on one map) that the sheer lack of size severely restricts the impact and import of the goings-on. In effect, it's a mini-game.

(Ed. note: sorry, but we've been informed that we can't use the term "micro-game" any more without Howard Thompson of Metagaming descending with mace and summons.)

This is further exacerbated by the fact that all jockeying for position eventually deteriorates into a game of musical cities: the French leave Madrid to take Cordoba, the British move into Madrid from Ciudad Rodrigo, whence another French force then sidles on over to the now poorly-guarded C.R., etc., ad naseum. It's like watching a giant, multilingual square dance, with a handful of poorly-colored pieces of cardboard dosey-doing all over the map.

There are other, albeit minor, problems. The Terrain Effects Chart is rather poorly explained, even given the fact that the map is relatively bare (and uninteresting, in that aspect). Some of the rules could be written a little more clearly, and in certain sections the main thrust of the rules is added as a note or an aside (viz., Section H on Alliances and the last sentence of paragraph "7"). The old AH tactical matrix pops up again. It is optional, and, lord knows, somebody must like it, but I always feel that AH is kicking a dead horse on this one. The designer's notes state that this rule was ". . . made popular in 1776"; despite my fondness for that worthy title, I would point out that nothing was made popular by 1776.

Ultimately, I focus on the designer's printed intent: "In recreating this classic military era, we have endeavored to design a classic wargame, a player's game, not an unmanageable historical treatise masquerading as a game." Aside from the fact that many "unmanageable treatises" type productions rarely "masquerade" as anything but dinosaurs (e.g., in my own CNA I go to great lengths to point out that the damn thing doesn't even approach being a game), the designer, and his usually capable developer, seem to have run into a problem practicing what they preach.

And there lies the playing paradox of War and Peace: it is a game that will leave both the player as well as the historian with an empty, unsatisfying feeling. As history it has only cursory flavor, flavor totally dissipated by a less than mediocre production approach. As a game it fares somewhat better; yet, it is not strong enough or consuming enough to warrant the repeated playings that define a player's classic. The scenarios that could do in this area are far too long, and the ones that can be played in one sitting are devoid of anything but the most circumspect interest.

The end result is a game of obvious merit in many areas that ultimately satisfies no one. The paradox is that a company with the marketing skill and lengthy development schedule of Avalon Hill could or would allow this to happen.

Back to Grenadier Number 9 Table of Contents

Back to Grenadier List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Pacific Rim Publishing

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com