GAME CREDITS

GAME CREDITS

Publisher:

West End Games, Inc

Helena Gail Rubinstein, President

PO Box 156

Cedarhurst, NY 11516

Copyright 1977 by The Morningside Game Project, Inc

Designed by The Morningside Game Project, Inc:

Vincent J. Cumbo, Albert A. Nofi, and John Prados

Developed by Daniel Scott Palter for:

The Morningside Game Project, Inc.

Graphics by Albert Zygier

Playtested by Matthew Aid, James Dingeman, Charlie

Elsden, Lenny Kanterman, Peter Kemp, Daniel

Scott Palter, Ricky Philips, and Joe Tysliava

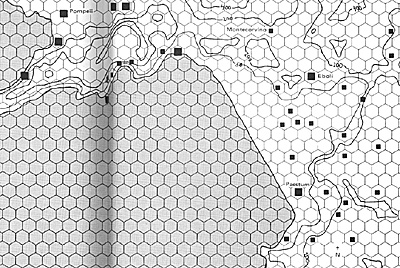

Sketch map of Salerno: Operation Avalanche; copyright West End Games, Inc.

While fans of the Russian front or Napoleonic campaigns enjoy a vast array of games from which to select, students of the WW II fighting in Italy have few titles to aid their understanding of this theater of operations. The major companies have rationed themselves to one game apiece, so most of the offerings have been produced by the smaller companies.

Recently, one of the newest companies, West End Games, has published the latest offering in this area - Salerno: Operation Avalanche. Salerno recreates the Allied invasion of southern Italy at Salerno in September of 1943. Regiments and battalions battle over a folio-sized map scaled at about one mile per hex. Each game turn represents twelve hours of real time, and the non-campaign scenarios last no more than eight game turns. Victory points earned by destruction of enemy units and occupation of geographic objectives determine the winner.

To digress momentarily, not until I exhibited Salerno at a university club did I understand why the Italian campaign gains so little attention from the major manufacturers. As I passed the game around, one fellow looked up from his Napoleon at War folio and declared that Salerno was not far from Wagram. A brighter lad, after much effort, managed to narrow down the time frame of the battle to between the invasion of Sicily and the battle at Anzio.

Apart from being a symptom of the declining quality of college undergraduates, this anecdote indicates that the Italian campaign has a low recognition value, hence low market appeal.

Unfortunately, Salerno will do nothing to enhance the average wargamer's interest in this area. Nearly every facet of the game has amateurish qualities in the disparaging sense of the word. In fact, Salerno is so easy a target for criticism that the temptation is just to unleash verbal broadside after broadside at it. But it does possess enough interesting aspects to warrant a close examination.

The components are responsible for the first impressions received from a game. For Salerno, the first impression is disappointment. Frankly, for eight dollars you don't get much. The ziploc bag contains a colorful cover sheet, a drab 16x2O inch unmounted map, 108 counters in German blue, American green, and British pink, an eight page rules booklet (though rules text covers only four pages), and the inescapable errata sheet.

The map is rendered in shades of gray and green on land and blue at sea. The land area includes the Salerno beaches, the surrounding mountains, and most of the Sorrento peninsula. Like GDW's Avalanche, contours of elevation define terrain types, although unlike Avalanche contours conform to hexsides in the same manner as rivers.

Clear terrain lies in the range 0- 50 meters, fair between 50-200m, poor between 200-400m, and bad terrain above 400m. (A friend of mine read these classifications and wondered if they were a subliminal comment on the quality of the game.) Towns, villages, roads, and streams complete the terrain types.

The accuracy of the map is acceptable but not outstanding. For some reason, the ruins of Pompeii cover a larger area than Salerno, and the supplemental contour lines in poor terrain are for decoration rather than information. Also, the TEC reverses the symbols for towns and villages. Not immediately obvious is the use of Italian names for the terrain features.

The village of Fattoria puzzled me until I used an unabridged Italian dictionary to learn that the name translates to "farm buildings", i.e., the Persano tobacco factory, a hotly contested location in the historical fighting. Unfortunately the Battipaglia tobacco factory, an equally important locale, is not included. Incidentally, despite the small size of the mapsheet, almost half of it is unplayable due to being sea.

Physically the counters are unusually easy to handle. They are large-sized, quite thick, and have rounded edges. In fact, they closely resemble the counters in the now- defunct Rand series of games (the significance of which will be discussed later). The counters have the standard format for type, size, and so forth, and have separate factors for attack, defense, and movement. All the German units are battalions, but in the Allied camp only armor, parachute, and shore engineers are battalions (about half the order of battle). Most of the Allied strength is concentrated in brigades and regiments. The evaluation of the unit strengths resulted in cookiecutter uniformity - 3-4-7 panzergrenadier battalions and 9-10-5 infantry brigades/regiments.

Accuracy in the order of battle receives much lip-service amoung wargamers, but few besides myself seem to enjoy long lists of unit designations. So I'll spare the reader a detailed account of OB shortcomings.

Let it suffice to say that the accuracy of unit designations is good for the Yanks, fair for the Tommies, and poor for the Jerries. Still, I can't resist pointing out one interesting flaw. The game has 3/351 reinforcing the three battalions of the 531st Shore Engineer Battalion; "351" seems to be a misprint in the U.S. Army's official history of the battle, a transposition of "531 ". Factors and not unit designations determine the order of appearance in the game. Once again accuracy ranges from best for the Americans to worst for the Germans. In particular, the Germans seem to be short-changed in receiving the correct number of units.

The first paragraph in the rules booklet sets the theme for the entire game: "Any reasonable disputes over the precise meaning or application of any specific rules should be settled by a friendly roll of the die". Beginners will roll the die about a dozen times, though experienced players should have little difficulty in arriving at reasonable solutions to the deficiencies. Some inconsistencies in the rules leave one wondering if anyone proofread the completed game.

The stacking rules provide a prime example: "Germans may not have more than two regiments plus two battalions or one regiment plus three battalions or five battalions on a hex at one time". As mentioned previously, the Germans have no regiments, only battalions.

The sequence of play cycles through arrival of reinforcements, amphibious movement (Allies only), ground movement, combat, and supply judgment (for the next player turn). Turning first to the minor rules, Allied reinforcements land at previously- invaded beach hexes except for some U.S. airborne battalions which paradrop anywhere "behind Allied lines" in clear or fair terrain. German reinforcements appear on map edge roads. The choice of a particular road is flexible enough that the Allied player can not detach lone units to sea[ off the "edge of the world" and prevent the reinforcements' arrival. Using amphibious movement, the Allies may transfer a limited number of units from one previously-invaded beach hex to another in a two-turn process.

For each unit the Allied player must pay a victory point penalty - one of the few good ideas in the rules. In Italy the tactical use of sea movement was as a delivery service, not a taxi service. Supply lines consist of a path five hexes long to a road leading to a previously invaded beach (Allies) or the map edge (Germans). The Allies may extend their supply radius by tracing a path to a beach engineer battalion which is itself in supply. In practice this is rarely necessary, and the battalions end up defending quiet sectors of the front. Lack of supplies prevents attacking and halves defense strengths but does not cause elimination.

For both movement and combat purposes, units are divided into "leg" and "mech" classifications solely on the basis of their movement allowance - a MA of 7 or greater defines a mechanized unit. On this basis the entire German contingent is mechanized, and almost all the Allied troops are leg. The TEC distinguishes between leg and mech units for MP costs, so that the latter enjoy a road bonus but expend more MPs to penetrate the higher elevations.

Thus the Germans have plenty of speed in clear terrain and on roads, but above the 50 meter contour line the Allied infantry becomes more maneuverable. For both leg and mech units, a good rule in the movement section prohibits a unit from attacking if it has expended its full MA. A major shortcoming to the realism of operational level games is the situation where a unit meeting no enemy opposition moves, say, 4 hexes, but in the same period of time it can move 4 hexes, fight a battle, and then advance after combat!

The mechanics of combat are fairly standard: fighting between adjacent units is voluntary and resolved on an odds-ratio CRT. But the procedure is considerably enlivened through the use of fire support, points added to the total attack and defense strengths of the units involved. The German player receives air fire support for both attack and defense, a grand total of points fixed according to a particular scenario. Out of this allocation, he may expend no more than ten points (in up to four 11 missions") per game turn. The Allied player receives naval fire support for attack and defense (for use within 8 hexes of the coast) plus a lesser amount of air fire support for attack only, again with maximum expenditure limits per game turn.

After the phasing player has allocated his attacks, both players secretly note down the fire support committed to each battle. The application of this procedure causes tense second guessing of one's opponent, for the expenditure of a few points may drastically change the odds of the battle, and the expenditure of many points may have no effect. Factors beyond the current fighting complicate the decisions: fire support may be needed in the following player turn, and use of fire support at the maximum rate will exhaust the allotment well before the end of the scenario. From the players' viewpoint, this is the most enjoyable part of the game. But from the historical viewpoint, how these point totals reflect the presence of air and sea power is anybody's guess.

Unfortunately, two other aspects of combat negate the satisfactions obtained from the fire support rules. One is the CRT itself. Plenty of IDEs and EXs force units to evaporate far faster than either the game or the history books can justify. In game terms, both players have relatively few units to simultaneously maintain security in quiet sectors, defend threatened areas, and mass for attacks.

By the end of a typical scenario, attrition has run so high that cohesive formations dissolve into scattered pockets of units incapable of carrying out these tasks. In historical terms, at no point during the battle were whole regiments wiped out to the last man in a single, twelve-hour engagement.

Apart from streams, which halve attacks across them, terrain benefits the defender only in modifications to the die roll, to a maximum of -2. A serious shortcoming of the CRT is that at 1:1 odds, a defender with full terrain benefit is in greater peril than if the die roll was unmodified. With no modifications, the probabilities of EX, AR, and DR are equal (33.3% each). But with a -2 modification, the probabilities shift to 33.3% AR and 66.7% EX! The defenders - usually the Germans - thus suffer an inordinate amount of casualties in relation to the amount of force used by the attackers.

The second shortcoming involves advance after combat. A rule straight from the dark ages of wargaming limits advance to mech units only. This bears directly on the victory conditions, which in part require occupation of four towns/villages. If the armored battalions have been victimized by exchanges or German counterattacks, the Allied army is essentially incapable of advance after combat. Thus the Germans can control a town/village indefinitely as long as a fresh unit can enter that hex before the Allies get a chance to move.

The choice of town/villages in the victory conditions was seemingly guided more by game balance than by history. The vital port of Salerno, for example, has zero value. Montecorvino Airfield is worth 15 VPs, but the rules place it in the same hex as Montecorvino village. Strictly speaking this is nonsense - the airfield lay on the coastal plain near the invasion beaches, not up in the mountains. But there is a grain of truth, perhaps unintentional, in the game's assignment. During the battle, shelling from the German-controlled mountains overlooking the airfield rendered it unusable.

The game provides three scenarios.

One covers the beach invasion with the help of some additional rules. In order to land the initial wave of units the Allied player must secretly record the beach hex each particular unit will invade. At the same time the German secretly picks half a dozen beach hexes for "defensive fire", an automatic 1:1 attack on any Allied unit landing there.

The Allied player may allocate a portion of his fire support to a preliminary bombardment before committing his forces, and if the hex bombarded is designated for defensive fire the attack is reduced to 1:2 odds. To add even more uncertainty to the invasion, each stack has a one third chance of drifting to the left or right of the intended hex.

The invasion scenario is short and basically balanced. After a successful invasion, the game usually comes down to a contested British advance across the poor terrain to Montecorvino, and a bloodless British/American thrust towards Eboli (delayed by German armored recon units which can retreat before combat).

However, a successful invasion is no certainty. In one game as the Allied commander, I ordered landings at six beach hexes. Drifting occurred at three. A U.S. infantry regiment met defensive fire at an unbombarded beach hex and was wiped out. In the other two cases, British brigades drifted onto already-occupied hexes. Because of overstacking these units could not move.

In the following turn, because of overstacking no reinforcements could land at these hexes and the units on the beach could move only half their MA. By the time the British sorted themselves out, the Germans had crushed the American landings and went on to a crushing victory.

The battle scenario begins where the invasion scenario ends. The Allies have a narrow beachhead and must expand it against a strong German defense. This scenario tends to favor the Allies because of the inadequacies of the CRT discussed previously. In an average game the Allies make no geographical progress for several turns but cause serious attrition for both sides. Suddenly the German player runs out of units and fire support points simultaneously; for the remainder of the game he must frantically juggle his positions to stave off collapse. A campaign scenario links the invasion and battle scenarios and adds some extra turns, but the outcome seems identical to the battle scenario. The Germans' "unit hunger" is worsened by the loss of five battalions which are included in the initial forces for the battle scenario but do not appear in the order of appearance tables.

All three scenarios include various "what if" options. In an admirable attempt to balance the game most of the options carry a victory point penalty. The penalties for using extra units are remarkably well chosen, but increased fire support seems too "cheap" for its effect on the game. In the haste to publish games nowadays, the playtesting necessary for such fine-tuning is all too often skipped.

Those familiar with the historical events may be somewhat puzzled by the scenario descriptions - why are the Germans on the defensive? In the battle, the Allies had to fight for every meter in order to establish a shallow beachhead, and then crushing German counterattacks nearly pushed them back into the sea. Only the leisurely arrival of the British Eighth Army from the toe of Italy finally forced the Germans to retire. In the game, the German battalions are usually no match for the Allied 9-10-5 brigades and regiments, and as noted previously the German player controls too few troops. On the other hand, if the lack of historical flow and the irritating rules omissions are over- looked (admittedly a tall order), then Salerno is rather enjoyable. The fire support guessing calls for clear thinking, and unlike the vast majority of wargames the rules can be described verbally in ten minutes. Perhaps secret, simultaneous plotting is a key contribution to enhancing player appeal in a game (as opposed to pure simulation): the less a game is playable solitaire, the better a game-player will like it.

Postscript

As a postscript, all the ills from which Salerno suffers seem to originate from its convoluted ancestry. The rules booklet lists only West End Games as the publisher. The Morningside Games Project holds the copyright, and printed on the countersheet, carefully obscured by magic marker, one finds "Rand Game Associates"! The counters themselves are certainly Rand format. For those who may not be familiar with Rand, the company appeared in '74 or '75 with a unique sales approach: customers subscribed to a series of games published (theoretically) at six to eight week intervals. The situation was analogous to receiving Strategy and Tactics with a game but no magazine. Rand later expanded into the retail market. Although some titles received good reviews, the quality of most was low; for instance, Hitler's Last Gamble became synonymous with the wargaming pits. Eventually Rand folded.

Morningside publically appeared soon after Rand disappeared, but it had actually designed part of the Rand product line. Morningside apparently gained the rights to these games, including Great War (for which Rand itself accepted orders and money but never released). Morningside then disappeared before it published anything, but West End Games surfaced and actually released Great War several months prior to Origins 79.

The evidence indicates that Salerno had been in the Rand pipeline through Morningside's efforts when Rand dissolved, and somehow the rights passed along to West End. Thus Salerno is an orphan - and the quality of the game suffers in consequence.

Back to Grenadier Number 8 Table of Contents

Back to Grenadier List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Pacific Rim Publishing

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com