My first experience with Marita-Merkur came in the spring of 1978 when the game consisted of nothing more than two hand-drawn maps and a sheaf of notes on OBs. At that time, wisdom held that Marita-Merkur might be impossible to crack. There would be no difficulty in putting maps, counters, and operational rules into a box labeled Marita- Merkur, but whether the sum of the components would equal a game was doubtful. Eager Europa-addict and newly arrived in Illinois, I was able to take the drafts home for study and play.

One week and several tests later, I returned the maps and notes with a report claiming that a game was actually lurking in the box. I'm not sure how much credence anyone really put in my evaluation, but everyone seemed pleased. Marita-Merkur went back on the production schedule a few weeks later.

I've learned that the production schedule at GDW is not the unyielding monster that it seems to be at other game companies. At GDW, it is relatively easy to get games on the schedule; it is considerably more difficult to keep them on track and release them when the timetable demands. Marita-Merkur, for example, had been on and off theschedule so often since 1973 that no one could count the number of times it had been aborted. Mounting public pressure to publish the damned thing, expansion of the Workshop R&D staff, and a general feeling that the game's time had finally arrived made it possible to break the production jinx. It was targeted for publication in January 1979, then March, and then Origins ... but this time it never actually fell off the schedule.

The project was a collaboration of efforts. Building on the basic Europa research and systems work of Frank Chadwick and Rich Banner, the team for Marita-Merkur included Frank, Rich, Marc Miller, Wayne Matthews, and Frank Prieskop, with John Astell handling much of the day-to-day design and development responsibility. I slipped out of my other Workshop duties enough to participate in most of the playtest sessions and development meetings.

Italo-Greek War

The first in-house game pitted me against Rich Banner to test the Italo-Greek War. Using the basic Europa system with which we were both very familiar, the contest rapidly degenerated into an Italian romp. We had come to our first hurdle. By rating the Greek forces on the same "pound- for-pound" basis by which all Europa forces were judged, they were unable to hold a defensive line . . let alone drive the Italians back into Albania. Historically, the Greeks -- while not really qualifying as Europa mountain troops - were much more flexible and adept at campaigning in mountainous terrain than were the Italians.

We promptly set out to discover a suitable game mechanism that would not require tinkering with the fundamental balance of combat factors. Several combinations of doubling, halving, attack mods, defense mods, and ignoring mountains were tested before a viable Solution was reached. This was the Greek mountain capability rule which modifies the die roll of Greek attacks into mountain hexes by +2. More playtests were run until we were confident that the Italo-Greek War worked within historical parameters and still allowed each side a chance of success.

Even so, some anomalies showed up in later stages of development. For one thing, the Italian Air Force proved too effective with the use of the increased bomb load rule. All the Regia Aeronautica machines tended to operate from quite short range in play and carry a doubled bombing factor that proved murderous; this seems to be at variance with the historical evidence of considerably poorer performance.

It has recently been proposed that the increased bomb rule be deleted from the game. John Astell experimented with "perfect plans" and found an optimal Italian first turn offensive that had a 4 in 6 chance of ripping open the Greek line and threatening to end the war with the early capture of Thessalonike.

A quick development huddle decided that it was not unwarranted to allow free set-up of some reseve units. Judicious placement of these troops prevents all but the luckiest Italian opening thrusts from overwhelming the Greeks before they can react. Such free set-up also helps prevent repetitious, standardized game openings.

With the first segment of the game locked up, attention turned to the German invasion. The first rehersal started with the historical situation at the time of the invasion and quickly pointed up the need for some modifications. The Yugoslav Army proved too resilient to the initial impact and it was decided to add a rule representing the rapid dissolution of the army due to defections by various ethnic groups. At the same time, the Germans found it impossible to blitz Greece on anything like the historical timetable.

The solution proved to be a Case White-style German invasion turn prior to the first full game turn. Several tests later, these conclusions were deemed satisfactory and the Yugoslav defection rule was finalized. (Co-designer John Astell has lately suggested a change in Yugoslav defection based on the ethnic makeup of each unit. Details appear elsewhere in this issue.)

Naval System

Up to this point, there had been considerable uncertainty about the naval system and the invasion of Crete. Playtesting the opening phases of the campaign continued while much thought was given to the naval problem. TFH had tackled some of the problem but there was (and is) no definitive Europa naval system. It looked like a tremendous task to finalize a practical solution for all of Europa with the man- hours available. Some initial work was done but scrapped when it became apparent that the game was beginning to resemble the Byzantine labyrinth of rules that characterized Their Finest Hour. Instead, we opted to go with a less definitive, more abstract, and immediately workable system that could serve Marita-Merkur and be fleshed out for later Europa games. The new transport rules were also plugged into the Italo-Greek scenario, reinforcements now appearing in Italy instead of Albania.

The combined air/land/sea nature of the Balkan campaign required a hard look at not only the naval system, but also the air transport and air assault rules of previous Europa titles. In Marita-Merkur, it became evident that specialized transport of divisions was usually done in piecemeal fashion with organic heavy equipment often left behind.

Using breakdowns with supported/ unsupported sides (as in TFH), it became much easier to simulate the requirements of air transport. No longer can entire divisions, replete with heavy artillery, tanks, and other equipment, be flown intact to a new location. With all this in mind, the air assault and transport rules were updated and the Merkur phase of the operations tested.

A lesson learned quickly testing the campaign game was the potential for turning Crete into an impregnable Allied fortress by transporting key troops there at the beginning of the game. The political restraints on naval transport are an outgrowth of this lesson.

The game was largely ready with the exception of the partisan campaign. The original plan had been to put the guerrilla operations into the box, but several factors prohibited it. The partisan campaign of Marita-Merkur needed to be compatible with the partisan campaign of Drang Nach Osten! and Unentschieden, however, those were (and are) undergoing revision and the partisan rules had not been finalized. The many conflicting interest groups and the hideously complicated political entanglements also seemed difficult to handle with just two players. With the Origins deadline beginning to loom in the distance, the decision was made to save the partisan campaign for an independent game.

With the bulk of the game completed and tested, the attention of the design staff and playtesters turned to finalizing the political concepts of assistance, intervention, and evacuation, and to settling the victory conditions. With five major belligerents, the victory conditions presented something of a challenge.

Each nation had its own goals, but the goals had to be compressed into objectives for two players: the basic political and military requirements for victory were set for overall Axis and Allied commanders. As in Case White, victory conditions were framed in game terms instead of military terms. Yugoslavia and Greece were doomed, but a gallant defense could earn a game victory. Trial and error was used to determine the correct weighing of victory points to create a balanced game. Frankly, there may be some question of how close we came.

My personal feeling is that it is a moot point. Europa games are complex historical models, not toys. I play Europa for the instructive value of historical content, not for the keen challenge of competition. To quote myself from a previous tirade, "the subtleties of historic necessity must suffice. Or, as someone else remarked, "if you have to look at the victory conditions to know who won, you're playing the game wrong". It was even suggested that Marita-Merkur (and other Europa games) dispense with victory conditions entirely. The rules for "how to win" were included, but that is no reason to obey them.

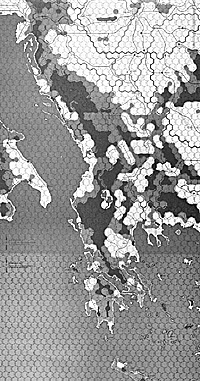

What did we finally get in Marita-Merkur? One and a half maps cover Hungary, Yugoslavia, Albania, and Greece with pieces of Italy, Greater Germany, Rumania, and Bulgaria. The coast of Cyrenaica is just off the southwest corner of map 15A. The color scheme follows the pattern set by Case White with green forests, brown hills, and dark brown mountains. A new Europa terrain feature is karst, effectively the same as impassable high mountain hexsides. Also making its premiere is weather line 'D'. All in all, the Europa maps continue to be faithful cartography rather than merely game boards.

There are 600 counters representing the entire air, naval, and land forces of both Yugoslavia and Greece, German Army, Luftwaffe, and SS contingents, Hungarian divisions, the British and Commonwealth expeditionary force, the Italians and four Albanian brigades along with numerous forts, airfields, and miscellaneous markers. The Europa color scheme for Italy is a lighter, screened version of German feldgrau, the Yugoslavs are white on chocolate brown; the Greeks are black on tasteful orange; Hungary uses black on bluegray. Other national colors are unchanged.

In addition to 20 pages of rules, there are two pages of notes, a map legend, two copies of the CRT/TEC, four pages of other charts, and five pages of OB/OA listings. The rules are in the traditional Europa format and, without a table of contents or index, are notably lacking in ease of access when seeking a specific rule. (The latest printing of Marita-Merkur includes an errata sheet with an extensive table of contents and a complete sequence of play.)

Ground System

The basic Europa ground system - as evolved through DNO, TFH, and Case White - is refined only slightly in Marita-Merkur. Notably, divisionsgruppen, cadres, and non- divisional units do not exert zones of control. New stacking limitations have been imposed in mountain hexes. Armor effects have undergone minor alterations, limiting the number of armor neutral units that can work effectively with armor.

A new class of engineers appears: assault engineers. The air rules are largely in line with Case White and the DNO air draft, adding a new type of airfield but differing importantly only in the air assault sections. Naval transportation, as mentioned earlier, is new and the political restriction rules for assistance, intervention, and evacuation are, of course, unique to Marita-Merkur. Weather is simplified; the Europa rules were just too complex to justify inclusion in a game with limited scope of time and geography.

My experience with playtesting has been that no matter how much I enjoy a game, I'm usually sick of it by the time it is published; I seldom get around to playing a game with "real" components until long after it is on the market. No so with Marita-Merkur. I looked forward to playing the finished product and did so at my earliest oppor- tunity after its release at Origins 79. (As traditional with Origins releases, there was not enough time to play in the few moments that elapsed between arrival of the last components and our departure for the con.)

My first post-publication contest can serve as a model of a fairly average campaign.

The Italians opened with a two- fisted assault on the center of the Greek line and the coastal road. There was no breakthrough; both sides took light losses and the Greeks lost two or three hexes. The orange units began immediately withdrawing from Alexandropolis, filling the Metaxas Line, and deploying to the Albanian front. The Italians made more headway on the second turn and occupied Corfu, but their bolt was shot.

By the advent of snowy weather in December, the Greeks were liberating their lost soil and penetrating into Albania. The Italians, continuing to pump fresh units into Albania, tried a flanking move along the Yugoslav border but came to a bad end in the clear terrain of hex 4216 ( ... dubbed the "Valley of Death" in playtesting). Losses continued to mount for both sides as the Italians were pushed back. The Metaxas Line looked very brittle and there was only the British 14th Brigade on the Aliakmon Line. The Greeks watched over their shoulders cautiously, but there was no German intervention or assistance.

By March, both the Italians and Greeks were exhausted along a line across Albania at the edge of the mountains where the Italians had thoughtfully built prepared positions beforehand. If playing with historical hindsight, the Greeks could easily have decided to penetrate less deeply and to pull more units out of the line to defend against the inevitable German invasion. This being a simulation and not a game of Old Maid though, most of the defense of Thrace and Macedonia was left to the newly arriving Commonwealth troops.

On April I, the blitzkrieg was unleashed across the Balkans. Albania was suddenly a sideshow, inconsequential beside the juggernaut that swept the Balkans. In the German invasion phase, the Yugoslavs deserted in droves along the entire frontier.

By the end of the regular Axis turn, the Allies were doomed. German mechanized elements knifed through the southeast corner of Yugoslavia and flanked the Metaxas Line. Thessalonike fell. The Aliakmon Line defenders were forced to retreat. The Allied airbases at Larisa were overrun and every airplane was destroyed on the ground. The entire rail line from Sofiya to Nis to Skoplje to Thessalonike was cleared and in German hands. The Hungarians were in control of the Backa. The Yugoslav Air Force was seriously damaged. Beograd was threatened. Zagreb was cut off and the Ljubljana gap was forced.

Most importantly, lightly garrisoned Athens was seized by elements of the 7th Flieger Division.

With both supply cities taken, the Greeks capitulated. The Commonwealth units of W Force began to fight their way towards Volos and the Royal Navy. The Yugoslavs attempted their own version of the national redoubt at Sarajevo while holding on to Beograd and trying to cut the Sofiya-Thessalonike line.

On April II, much of W Force was destroyed, and the Germans began withdrawing panzers from Greece and setting up forward bases for the invasion of Crete. The remnants of W Force abandoned their weapons and were withdrawn to Egypt. Over the next few turns, the dwindling Yugoslavs were handled mostly by the Italians.

On May II, Merkur was launched. Three regiments of 7th Flieger assaulted the airfield west of Khania while other elements of that division and 22nd Luftlande landed adjacent to the field to attack with air support should the initial assault fail.

Three other regiments were loaded in transports to land at the field as soon as it was captured. The air assault took the field and eliminated the garrison at a cost of a parachute regiment. The Royal Navy interdicted the coastal waters of Crete for the remainder of the campaign, putting the German invaders out of supply and turning back attempts to transport reinforcements by sea.

Hampered by lack of supply and support, the Germans managed to take Khania (with the loss of more paratroopers) after flying in regiments of the 1st Mountain Division, but the surviving British garrison held out successfully in the mountains on the final game turn. As the Balkan campaign ended and Barbarossa began, the island of Crete was disputed but doomed to fall.

Victory point totals were not tallied, but the game was obviously a resounding Axis success. I've also taken part in a decisive Allied victory ... though admittedly on the wrong side. (And I'd like to point out that my play turned somewhat whimsical after a 1 in 6 chance of poor weather in April delayed German intervention and I failed to capture the final Yugoslav supply city in April on another 1 in 6 chance.) The game offers ample opportunity for either player to win a major victory.

Campaign Game

The campaign game divides itself into four separate but interdependent operations: the Italo-Greek War, the invasion of Yugoslavia, the invasion of Greece, and the Crete landings.

The Italo-Greek campaign resembles the slow and ponderous process of war in the trenches during World War I. The Italians are able to launch an initial strike that should gain several hexes (the "Astell" plan utilizes every Italian ground and air factor to make four 3:1 attacks against the usual Greek deployment), but the timely arrival of orange reserves usually shuts down the Italians.

After the second or third turn the Fascist army can generally make but one effective attack per turn and a competent Greek commander can take the initiative. The key to the Greek offensive is the combination of the +2 die modification and the optional (often called "bloody") columns of the CRT. Originally included in DNO for use in desperate low odds breakouts from encirclements, the optional columns and the die mod allow the Greeks to lever their opponent northward slowly but surely. At 2:1, an attack with +2 mod automatically takes the hex, and at 1:1 there is a 5 in 6 chance. Given these odds, the best the Italians can hope for is to bleed the Greek and lure him into Albania, conserving strength and giving ground no faster than necessary.

Italian success, however, is not impossible. Depending on the Greek deployment, there is a chance that the center of the line can be crushed immediately and the 133rd Armored Division can rumble towards Larisa. This takes most of the fighting out of the mountains and the Greeks lose their advantage. Alternately, it is possible to turn the Greek flank and push the armored division down the less mountainous terrain along the coast; this does stretch the front and expose the Italians to the chance of isolation if the Greeks can pierce the center of the line. Both of these strategies have worked for the Italians, but the experianced Axis player will be sure to erect a solid chain of fortifications across Albania along the northern edge of the mountains ... just in case.

Players with the original printing of the game may be wondering just how wise it is to penetrate all the way to that chain of fortifications with the Greeks. According to the original rules, it is possible for the Allied player to keep a careful tally of victory points and try to win without penetrating so deeply and thus not gaining enough victory points to trigger German intervention. By making just sufficient headway that the Allied victory point total is greater than the Axis total but not double that total (admittedly, not an easy task), there can be no German intervention. Presto. Al I ied victory.

(But this is only a marginal victory and depends upon the Italians, with their later reinforcements and probable German assistance, not being able to push back into Greece in the last few turns - the editor)

Likewise, by playing carefully to minimize the probability of the Yugoslav coup, the Greeks can write off the German threat even if intervention does occur. Why? No Yugoslav coup means the Germans may not enter that nation; without the Yugoslav rail net, the German intervention army can not be supplied in Greece. Presto. Allied victory.

Both of these anomalies have been removed from Marita-Merkur in the current edition of the errata sheet. Basically, there is always a chance of German intervention anytime the Allied total is ahead of the Axis; if there is no coup, then then Germans can trace supply through Yugoslavia.

German Intervention

Assuming the Germans intervene, as they almost certainly will, their work is cut out for them. Yugoslavia may appear a temptingly vulnerable target at first glance, but there are important facts to consider:

- 1) It is often possible for the

Allies to set up a "national redoubt"

around Sarajevo which preserves a

supply city and keeps the Yugoslavs in

the war indefinitely.

2) If the Yugoslav coup is triggered ahead of intervention, the defensive posture of its entire army can be radically improved.

3) The importance of blitzing Greece draws off the majority of German troops and leaves only limited forces to deal with Yugoslavia.

Under all circumstances, Yugoslavia must play second fiddle to Greece. Beograd may look vulnerable to a pincer attack, but the responsibility for everything north of Nis is strictly that of the German Second Army, the Italian Second Army, and the Hungarians.

If the Axis player has hopes of clearing the mainland and seizing Crete by the end of June, every effort must be made to seize (and protect) the SofiyaNis-Skoplje-Thessalonike rail line, as this is needed to supply the formations in Greece. The panzers should flank the Metaxas Line through southeastern Yugoslavia, slip into Thessalonike, and attempt to race across the peninsula far enough to isolate the Greeks in Albania. Originally, the German 7th Flieger was sometimes dropped on the first turn to seal off Athens and isolate all the Greeks in the north (see the battle report above).

Actually, evidence indicates that the division was not actually combat ready that early and could not drop (see the new errata). Nonetheless, it is still entirely possible to bag immediately large quantities of orange units by isolating them.

The Allies may conduct a fighting withdrawal from the Aliakmon Line in the north or initially attempt to stand near Thermopylae on the Sperkhios River. In either case, it is imperative to destroy airfields and railroads and to hold Athens and the Peloponnese as long as possible to disrupt the German timetable. It becomes mandatory at the end of the game to decide whether it is possible to maintain a toehold on the mainland or if it is necessary to declare the evacuation and attempt to hold Crete.

Crete

While simulation at the Europa scale makes the Crete landings quick and sketchy, they are not unfaithful to the tense and risky histoical undertaking.

The German paratroopers must seize an airbase to land air transported reinforcements; without reinforcements, they are weak and vulnerable. The Allies must defend the airbases and also hold one port to keep themselves in supply. Unless they have managed to maintain aircraft in the game and based on Crete, the Allies, however, have no need for airbases and can destroy the Heraklion and Maleme fields.

This leaves only the less useful fields of the reference cities: any number of air units may land there but only one unit may take off in a turn, creating a jumble of parked and useless aircraft. The parachutists should select one or two target hexes with some kind of landing facilities and seize the target with an in-hex air assault to permit the immediate build- up of airlifted reinforcements.

Once established on a field, the Germans must conquer the entire island with limited strength in a short period of time - not an easy task. The difficulty is that the Axis units are almost always halved for lack of support and often halved again for lack of supply due to Allied naval interdiction. This puts a premium on the Axis airpower advantage which can provide the punch that makes the difference in what will otherwise prove to be a featherweight "slugging match" along the lines of 1.75 attack factors against 1.50 defense factors.

In trying to summarize my feelings about Marita-Merkur I am somewhat hampered by being far from an objective observer. I am after all a Marita-Merkur playtester, a Workshop staffer, and a writer for this magazine. I don't think any of that colors my thinking when I say that Marita-Merkur is the best game I have played in many months.

I am not blind to its flaws, though. Perhaps I am merely an old Europa dog unable to learn new tricks, but there is much about Marita-Merkur that is poorly presented and difficult to assimilate. The basic concepts of Europa movement and combat systems are finetuned and readily usable. However, the special political/diplomatic background required a layering of unique rules that suffered the double drawback of having the least rooting in previous Europa games and the least independent testing. This led to the anomalies (now corrected) in the rules for intervention, German supply, and Greek dissolution. Had these rules received more testing (or had I grasped them earlier), they might have been repaired before publication.

The naval system (not greatly used in play) also bothers me, though this could be strictly a personal prejudice against naval systems in general. (And I have to add that during development and testing, my position was that the present system was the only one feasible under the circumstances.) Nevertheless, from a player's viewpoint, I'm sorry not to have a final Europa naval system.

Much of the difficulty in learning and playing Marita-Merkur resides in the inaccessibility of the rules - everything is there, it is just difficult to locate. For example, the airborne rules are given partly under Special Air Rules - Gliders, partly under Airborne Operations, and partly under Air Missions - Air Assault. Without a table of contents or index, searching for a particular ruling can be time-consuming and infuriating.

Rewards

One of the most rewarding aspects of post-publication play and writing this article has been the immediate response to get trouble areas cleared up. The new errata features a complete table of contents and a complete sequence of play. These should help tremendously to facilitate the flow of the game. The same errata takes care of the other problems uncovered in post-publication play.

Within the framework of the rules, it is possible to explore every facet of the campaign. A historical outcome can be achieved without resorting to choreography, and there is a great premium on thoughtful, innovative play. Players must learn to handle a wide assortment of unit types under a variety of conditions; all in the face of a capricious (but historically conceivable) diplomatic future. Historical lessons are faithfully taught at every turn.

What this gives us is a richly detailed and accurate simulation of the Balkan campaigns.

Marita-Merkur is definitely not a beginners' game, and perhaps not a game at all in the sense of a superficial, relaxing contest. Instead, the same complexities that make Marita-Merkur difficult to unravel and learn also make it a subtle and supple tool, an engrossing, educational and enjoyable model of the multi-national air/land/sea operations in the Balkans, an opportunity for imaginative manipulation of cardboard armies.

That may sound like an

advertisement, but I mean it. Fans of Europa

and fans of historical simulations should

enjoy Marita-Merkur. I know I do.

An Apologia

Being both editor of this magazine and co-designer of Marita-Merkur, I find it irresistable to comment on one point of the preceding article. Mr. Stone is entirely correct in the fact that the rules absolutely need a table of contents. I had drawn one up but had to discard it when the air rules were reformatted. In the pre-Origins rush, I simply forgot to write up a new one. A table of contents and the latest errata (dated 24 Oct '79) is available.

Back to Grenadier Number 8 Table of Contents

Back to Grenadier List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Pacific Rim Publishing

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com