It is a surprise when the realisation comes that no-one in one's offices was born at the time one started one's first job in the book trade, although the first job still seems fresh.

In the spring of 1954 – an amazing forty-five years ago – I joined the Handel Smithy bookshop in Edgware at £ 3.20 per week (Saturday included, but with a half-day on Thursday). No, those were not the days of gas light, or the penny farthing bicycle.

The Handel Smithy Bookshop was a typical small independent shop run by a very untypical owner. The owner was Gerald Konyn, a wonderful bookman but a bad businessman. He was brilliant as a salesman, and could charm local ladies into buying books they wanted but could not afford. One fine series at that time were the Skira artbooks, which were the first of a new post-war generation of top quality artbooks. Those who looked upon them with admiration, but thought that they were out of their financial reach, were soon talked into a 'pay away' plan by Gerald Konyn, and loved the books and him for making it possible for them to acquire them. He was truly a bookseller customers could rely upon for recommendations, and at the time that Nicholas Monsarrat's The Cruel Sea was a bestseller, in its day without parallel, we were selling to his regular customers another book, which nobody had heard of, in greater quantity.

Soon after joining the shop I had to go to the warehouse of the bankrupt wholesaler Simpkin Marshall to buy books that were being sold off by the receiver. It was this event which sounded the warning to the book trade of Captain Robert Maxwell's way of doing business. Books that were first published in the middle 1950s, and which had to be sold without their current fame and critical acclaim, were Tolkein's The Lord of the Rings, Golding's Lord of the Flies, and the first Ian Fleming James Bond book. I was able to talk a number of regular customers into Tolkein's Lord of the Rings, although at the time there was no precedent for a book about a mythical world. There was indeed quite a remarkable credability gap, but those customers who took Lord of the Rings away were enthralled, and as there was a period of time between the publishing of the various volumes we received any number of enquiries from impatient cusotmers who were concerned about Frodo being left hanging over a cliff edge until the next volume came along.

In the 1950s there was a sensational radio serial called Journey into Space. The producer and writer Charles Chiltern lived close to the shop, and so too did one of the actors. The shop made an arrangement for an autographing party and as part of this, in order to set up a display in the window in Edgware's Station Road, the publisher Herbert Jenkins supplied what in the 1950s was regarded as a spaceman's suit. This was a white rubber affair, with rings of air which needed blowing up, plus a glass bubble helmet. This was made for display purposes only, but Gerald Konyn had the great idea that if I were dressed in it, and the suit was inflated, and I walked along Station Road, this would attract considerable attention, press photography, and so forth. And he was right. After I had got into the outfit and it was inflated my arms stood out by my sides, away from my body, rather like a Michelin man advertisement. The helmet was put over my head, and affixed by bolts to a ring around the neck of the suit, and I started my walk, or rather waddle, up Station Road. However I soon discovered a little problem. Because the suit had been made for display purposes only there was no air vent to the helmet. And then because there was no air vent, the air seemed to be getting a little thicker inside the helmet and the helmet started misting up. I started gesticulating towards the helmet, to try and get attention to this problem, but nobody understood and in fact they thought that my waving of my arms was rather funny, in an alien sort of way. It was only when I lowered myself to the ground and started beating the perspex bubble helmet on the pavement that the crowd realised that I had a problem. This was of course a good introduction into the perils of book publicity.

Most unfortunately Gerald Konyn's wife was seriously unwell, and even in those dark days of Cold War he managed to arrange for treatment at a spectaular centre behind the Iron Curtain in Hungary. This meant however that he was away from the shop for extended periods, and he left the running of it in the hands of a callow youth in his very first job in bookselling. Hence I had to take over the ordering of the books, which was a great experience in dealing with sales reperesentatives and learning how to control a sales presentation by taking from their hands the sales kit. The downward side however was that only Gerald Konyn could sign cheques, and with his extended absences this caused all sorts of problems, another introduction to the problems of commercial life.

I think that getting into book publishing via bookselling should be obligatory for all on the sales, marketing and commercial side of publishing, and probably editorial as well. One learns a great deal from handling books, speaking to the customers, seeing the reactions of customers and understanding their needs. Even after forty-five years one can still remember customer reaction (such as when the Guinness Book of Records was being newly published, and the shop was being used for test marketing), book jackets, and so forth.

In 1956 I moved on from bookselling to book publishing, and coincidentally joined Herbert Jenkins who were the publishers of Journey into Space. But that's another story.

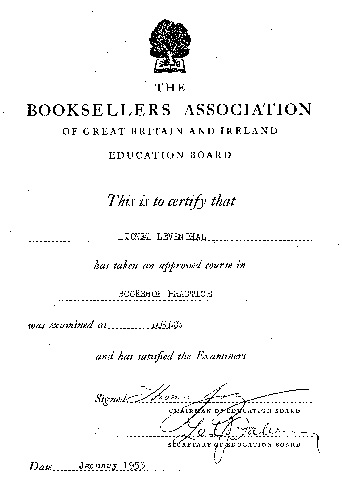

Levanthal's "Bookshop Practice" Certificate

Back to Greenhill Military Book News No. 89 Table of Contents

Back to Greenhill Military Book News List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Greenhill Books

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com