An exciting new manual on the art of hostage rescue is being published by Greenhill this summer.

Hostage Rescue Manual: Tactics of the Counterterrorist Professionals is a comprehensive, illustrated source on the dynamic operations which have saved hundreds of lives. It is based on strategies which have proved successful in hostage incidents around the world, including the landmark SAS rescue at Prince’s Gate, London. The author, Leroy Thompson, has trained military and police hostage rescue and VIP protection teams around the world and has written a number of books and articles on the subject. He writes:

“When hostages are taken, the incident evokes a combination of horror and empathy among a country’s population. At the same time, unless a response is carefully planned and successfully carried out, a government can appear impotent or non-responsive to the dangers facing its citizens. Often, the details of hostage incidents are kept from the press and the population to protect the hostages and those tasked with saving them. As a result, though incidents may end through negotiation or through armed action by security elements, only the sketchiest details of how the operation was carried out are normally available.

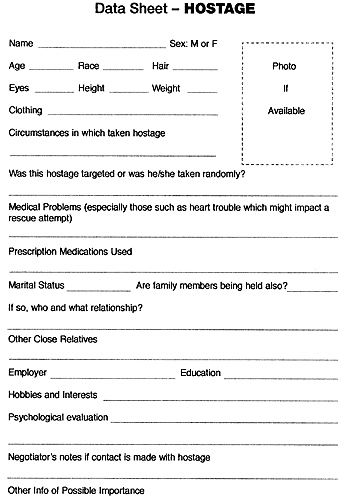

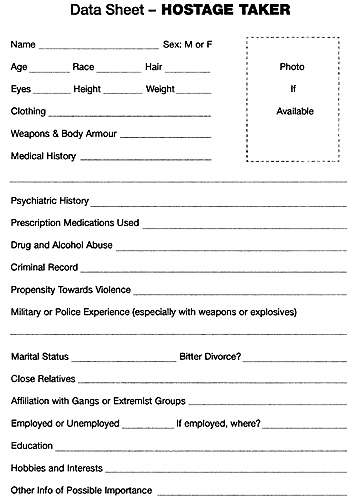

In this new book I’ve attempted to assemble a guide through the process of hostage rescue both for those who work in security-related fields and those who want to understand better the missions and skills of those who silently protect society from those who would use the threat to innocents to extort concessions. Much of the information contained in this work is based on my own experience in training hostage rescue units in various parts of the world, while other information is based on standard operating procedures of some of the most successful international, national, state and local SWAT or Tactical Teams.

Rescue tactics and standard operating procedures differ from country to country based upon form of government, culture, religion and a myriad of other factors. In some countries, for example, hostages of a certain race, sex, or caste might be considered more valuable hostages than others. Even in democracies where theoretically all are equal, a rich, influential hostage will naturally be regarded as valuable by hostage-takers hoping to prompt a significant response from the authorities, who will experience the added pressure of media scrutiny. Cultural influences may also play an important part in how an incident transpires. For example, at least one incident in the United States was resolved because the leader of the hostage-takers was disconcerted by the necessity of performing bodily functions in close proximity to the hostages. His fastidiousness influenced him to end the incident peacefully and more quickly than would have been likely otherwise.

The differences in police authority will also influence the handling of a hostage incident. In Great Britain where only a limited number of police are armed, for example, it may take longer to have armed containment per-sonnel on the scene, though the use of armed response vehicles has allowed a much faster response than formerly. The weapons culture in the United States is such that as many as 50% of homes contain firearms of some kind. The likelihood of encountering an armed suspect in a ‘hostage’ or ‘barricade’ situation is therefore much greater than in the UK and US HR units train accordingly, placing greater emphasis on the need to secure a site on entry and confront - rather than simply contain - the terrorist. The issue of investment generates further distinctions in practice. It may be surprising to the layman to learn that one of the largest markets for HR work is occupied by smaller teams with tight budgets, who are often tasked with maximising the limited resources they have access to. On the other hand, wealthier countries with highly trained police or military rescue units will also be more likely to have access to the most modern and most sophisticated equipment and weapons as well as intensive training programmes. The more authoritarian the government, generally the more likely there will be pressure on response units to act quickly to end the incident to prevent the perception of the government as weak. More democratic gov-ernments, on the other hand, will be under pressure to place great emphasis on the lives of the hostages.

I have endeavoured to help the reader und-erstand that a successful hostage rescue operation is a mosaic composed of many skills and many individuals, each of vital importance. While the negotiator attempts to use his empathy and understanding of psychology to end an incident peacefully, he is also gathering intelligence which may assist an entry team if they are needed. The intelligence experts are constantly upgrading and updating their intelligence about the hostage-taker, hostages and site, through technological and other means. Silently observing the incident, prepared to end it with one precision shot, are the snipers and observers. Meanwhile, the entry team-the men in black wearing gas masks and carrying submachine guns-refine their plan in case they are called upon to provide the ‘final option’.

From the initial establishment of a perimeter to contain a hostage incident, until its successful conclusion through negotiation, the ‘green light’ order to a sniper, or a dynamic entry, the Hostage Rescue Manual allows the reader to follow the progress of a hostage rescue incident in detail.”

Back to Greenhill Military Book News No. 107 Table of Contents

Back to Greenhill Military Book News List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Greenhill Books

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com