The leading image of the Soviet Union's war effort in World War II has remained the same over the years: swarms of infantrymen clutching submachine guns, riding T-34 tanks into the streets of European cities.

This image is close to the mark, as the Blitzkrieg warfare of 1941 on the Eastern Front gave way to vicious close actions in the streets of ruined cities like Rostov, Sevastopol, and Stalingrad, where gains were measured in yards and trophies were buildings reduced to rubble. The great mass of the Soviet steamroller that stormed across Eastern Europe in 1944 and 1945 was an infantry army. The final battles of the East Front were again house-to-house actions that reduced great cities like Berlin and Budapest to rubble. These battles were decided by the personal weapons carried by the average Soviet infantryman.

Pistol

Pistol

The primary Soviet pistol was a simplified version of the 1911 Browning, rechambered for 7.63mm Mauser ammunition. The Soviets had large stocks of these weapons on hand, and the weapon was named the Tokarev, after its designer. It was a robust and effective weapon, that worked well in Russia's difficult weather. However, despite the pistol's glamour in the West, the Soviets were not too keen on them. Pistols seemed a defensive weapon, and were used by vehicle crews for selfdefense and by staff officers.

The favorite Soviet weapon was the submachine gun, which could spew out a high volume of fire at close range, a fact appreciated by gangsters, commandos, and producers of action movies.

The Soviets produced their first military design in 1934, the PPD 34, by Degyarov, which was a wooden stocked weapon with a long barrel and a loaded weight of 12 lb. That was extremely heavy, but it carried a respectable reserve of ammunition. The weapon fired a 7.62mm round, like Soviet pistols. The weapon could be sighted at up to 500 meters, but probably had a range of a good deal less, as the light bullet traveled quickly, but also lost momentum quickly.

In 1940, the Soviets brought out the PPD 40, which was a simpler weapon, using good quality steel and chrome barrel. This weapon only lasted until 1941, as it proved inferior to the Finnish Suomi submachine guns in the 1939-40 Winter War.

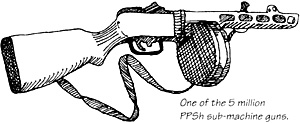

PPSh

PPSh

To compensate, Georgi Shpagin developed the submachine gun that would be carried by more Soviet troops than any other weapon: the PPSh-41 submachine gun. More than 5 million of these weapons cranked off production lines by 1945, and production went on in the Soviet Union and its client states for many years. It had a wooden stock, long barrel, perforated barrel jacket, and drum magazine. The weapon weighed 8 lb., was 33 inches long (838 mm), and could put out an incredible 900 rounds a minute. Muzzle velocity was 488 meters per second (1,600 feet per second).

The PPSh, known as the "Pay-Pay-Shah" to its users, was more accurate and easier to hold on automatic fire than the PPD, because the bolt was more carefully designed and balanced to its spring, and some care taken to get the buffer right. The end was sloped to deflect muzzle blast, which instead increased its noise.

One of the attractive features of the PPSh was its ease of maintenance. It could be fieldstripped by opening the receiver and taking out the bolt. Daily maintenance was restricted to cleaning and oiling, and the weapon could survive long periods of mud, dirt, water, ice and snow, and still go on firing.

The PPSh was stamped and either seamed, welded, or pinned together, but the chromed barrel of pre-war submachine guns was retained, as was the drum magazine, which carried 71 rounds.

The PPSh, however, was a complicated weapon to load. Soviet infantrymen had to remove one of the cover plates, wind the spring, lock up the spring, insert each round individually, release the spring under control, replace the cover plate, and straighten the first round or two to be pushed out. A very difficult task under fire. Soviet troops preferred to replace guns, not drums.

PPSh dominated the Russian submachine scene for the duration, but there were others. The PPS 42 was designed by Sudarev in Leningrad, during the great siege. Soviet troops holding the city lacked submachine guns, so they were made in an arms factory on the spot by famished workers.

PPS 42 was entirely metal in construction, except for the pistol grip, which used either wood or plastic. It only fired on automatic, with a box magazine of 34 rounds. The 71-round drum was beyond the besieged city's resources. The weapon weighed 8.5 lb., fired 7.62mm ammunition, and was 32.72 inches long with stock. More than a million PPS 42, and its successor, the PPS 43, were made.

The Soviets put PPSh 41 to good use, and by 1945 led the world in tactical use and employment of submachine guns. Their main development was the "tank rider battalion" of 500 men, all armed with PPSh 194 Is. Each squad traveled on its own tank. When the tank was knocked out, the squad climbed onto the one behind. Casualties were immense. Traveling on the outside of a tank in peacetime is extremely difficult. In wartime, under heavy enemy fire, with the tank gun firing and the turret traversing, it seems suicidal. The life expectancy of such outfits must have been short.

A British officer who met up with such a unit in 1945, and wrote that they seemed little better than animals with an almost total disregard for human life and suffering, and a simple and brutal disciplinary system. Supply seemed to have been based on looting and capture. It was these battalions that gave rise to the "Bolshevik Horde" image of Soviet troops raping and looting their way through Germany.

Tactics and training were equally simple. Tank rider battalions only practiced offensive maneuvers. Any time they ran into opposition, they charged it, whether on foot or on tanks, regardless of weather, relying on numbers, firepower at close range, and shock to dislodge the enemy.

These tactics worked, as the submachine gun is the weapon of a determined soldier, and the Soviets showed ample determination in battle after battle.

Rifle

Rifle

The Soviets used four different types of rifle during the war, but all used the same ammunition. The basic weapon was the MoissinNagant 1891, developed by a French-Belgian team. The a bolt-action five shot rifle that dated back to 1891, and was one of the oldest designs to be used by a major combatant. The bolt was a two-piece weapon, and its sighting system was based on airshins, the pre-1917 Russian measurement unit.

The Soviets swept this away with the 1891/30 model of the rifle in 1930, which used the metric system on its leaf sight. it also had a circular foresight guard to protect the blade. A sniper version was produced, which the Soviets put to good use. Soviet propaganda glamorized their snipers.

It was fitted with either a PY (x3.5) or PE (x4) telescopic sight. The rifle was 1.304 meters long (51.25 inches) and quiet heavy at 4.43 kg (9 lb. 10 oz.) Barrel length was 802 mm (31 inches).

On the whole, the weapon was cumbersome but robust, gaining a reputation for reliability, but obsolescent. Many Moisin-Nagants fell into German hands, and were used by Wehrmacht formations, most notably the "Ost" battalions that faced the invasion of Normandy. In German hands, the Moisin-Nagant M 1930 was renumbered the Gewehr 254.

In 1936, the Simonov AVS M1936 appeared, a self-loading rifle, followed by Tokarev's SVT M1938. The former was gasoperated and locked by a vertical block, capable of semi or fully automatic fire. But it was too fragile for heavy combat.

The SVT, its replacement, had a 10-round magazine and a twopiece stock, incorporating a perforated steel sheet hand guard designed to aid cooling, and similar holes were cut in the furniture above the barrel. This made it fragile, and its performance in the Russo-Finnish War was disappointing. It was not easy to strip and did poorly in winter. Numerous rifles fell into Finnish hands, and they sold them to arms collectors as curios.

SVT 1938 was replaced by SVT 1940 in that same year, a stronger weapon, which weighed 4.9 kg (10.8 lb.), was 1,222 mm (48.1 inches) long, with a muzzle velocity of 830 meters per second (2,720 fps). The barrel was 635 mm (25 inches) long. Thousands were made an used, but it could not compete with the MoisinNagant, and the SVT production line was shut in 1944.

Machine Gun

Machine Gun

Each Soviet rifle squad was to have a light machine gun for backup fire, and the Soviets demanded a new machine gun in the 1920s, after the Red Army was reorganized.

The result was the Degtyarev DP 1928, invented by D.A. Degtyarev of the Tula Arsenal in 1927. The entire weapon had only six moving parts, a model of simplicity, and weighed barely 26 lb. The DP 1928 used a thin flat metal magazine with 47 rounds of 7.62 mm ammunition, to lie in one layer with only their bullet points inwards to the center. Three pans were carried in a tin box that protected them, but the box was unwieldy. Later in the war, machine gunners used canvas bags.

The DP 1928 was 1,290 mm (50.8 in) long, had a 605 mm (23.8 in) barrel and weighed 9.12 kg (20 lb. 8 oz.). It fired fully automatic at 550 rpm and had a muzzle velocity of 840 m/sec (2,760 fps).

The DP was blooded in the Spanish Civil War and was a success-it became the standard weapon of the Soviet Army and another one of their enduring images with its distinctive pan magazine.

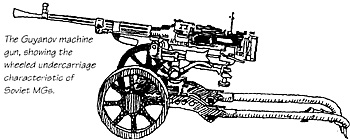

Another distinctive Soviet weapon image was the heavy, wheeled machine gun. The standard weapon was the Maxim PM 1910, a standard Maxim medium machine gun that entered Russian production in 1905, and versions continued to be built until 1945.

Firing 7.62mm ammunition, this weapon topped the scales at (23.8 kg) 52 lb. for the bare gun. That made for poor mobility. The weapon's action was recoil toggle-lock system and the weapon was reliable. It was 1,107 mm (43.6 in) long and had a 721 mm (28.4 in) barrel, firing at about 550 rpm off a 250-round fabric belt. To move it, the Russian slapped little wheels on the mount.

In the early days, Soviet machine gun units moved with horse teams and all, field-gun style, but one could not bring horse teams in close proximity to the enemy.

The Soviets added a bullet-proof shield and the weapon now weighed 152 lb., which made it a struggle to move, even with the wheels, through Soviet mud, ditches, and sand. After six months of fighting, Soviet machine gunners tossed the shield onto the steppes. This machine gun was clearly a failure.

An attempt to replace this weapon was the Guryunov, but it never completely displaced the Maxim. The Guryunov was an air-cooled gun, about 20 lb. lighter, and offered a quick-change barrel. It could stand up to 500 rounds of continuous fire before needing replacement.

Hand Grenades

Hand Grenades

Hand grenades were an important tool of the Soviet infantrymen, who regarded them as "pocket artillery." In World War 1, Russian troops fought with stick grenades. This was improved into the Model 13130, a simple blast grenade. A sleeve could be added to provide splinter or fragmentation effect. The explosive used was trinitrotoluene. Weight was 0.6 kg (1 lb. 5 oz.) and was 230 mm (9.3 ins) long. This grenade was simpler than its replacement, the Model 1933.

The Model 1933 required manual dexterity, as the handle needed to be pulled, turned, and a safety catch slid over, before throwing the thing. Not a very popular weapon, as in the heat of combat, there was too much to remember about which way to turn it and which steps to follow in which order.

The next grenade was the F-1 fragmentation grenade, which looked like Western grenades, a neater and easier weapon to throw. Filling consisted of TNT. The lever flew off horizontally when the grenade was thrown, removing the cap and releasing the striker as it did so. This grenade weighed 0.56 kg (1 lb. 4 oz.). It was the most reliable and best-used of their grenade designs.

For anti-tank use the Soviets first used a high-capacity stick grenade, which was superseded by a hollow charge pattern RPG 43, which used a rifle rod and blank cartridge for launching. A hollow drum tail helped to stabilize it in flight; this tail unit was carried on the grenade body when loaded, and the shock of launch loosened it from a spring retaining clip so that it slid down the tail rod when fired so as to give the desired length of tail for great stability, a complicated manufacturing proposition. It weighed 1.24 kg (2 lb. 12 oz.).

The collapse of the Soviet army in 1941 left behind most of its heavy guns for the Germans to capture and the Russians in need of a replacement. Mortars, being cheap and easy to produce, soon filled in. The first Soviet mortar was an unusual 47mm weapon which included a spade that rested up on the ground when the weapon was being fired. If the troops weren't fighting, they could use the spade to dig foxholes or firing pits. It did not seem to work in either area, although it apparently could hurl a bomb of 1.5 lb. about 400 meters.

More conventional were the Model 1938 and Model 1939 mortars, which were both drop-fired and operated at a fixed elevation. Their range was altered by bleeding off gas through a valve leading to an exhaust pipe which lay beneath the barrel. Little else is known about these weapons.

They were replaced by the Model 1940, which had an improved baseplate and stamped-steel bipod. Two fixed elevations of 45 degrees and 75 degrees were available.

The company weapon was Model 1936 or Model 1937, both 82mm mortars. The former was issued in small numbers and superseded by the latter. The 1936 was a conventional drop-fired weapon based upon the original Brandt designs, while the 1937 version improved it by clamping the barrel to a bracket which was held to the bipod by two spring shock absorber units. This allowed the barrel a certain amount of recoil back on to the baseplate without transmitting too much disturbance to the bipod. The finned bombs had a six-part charge, which enabled mortar crews to change range by adjusting which charge they wanted. Maximum range with an 8-lb. bomb was 3,300 yards. The whole equipment weighed 111 lb. and stripped into three loads.

Mortar

The Soviets also produced the best German mortar of the war, a 120mm weapon, which fell into Axis hands. The Nazis, impressed with it, put it into production as Granatwerfer 42. However, the weapon was perfectly useful in Soviet hands, firing a 34 lb. bomb to 5,700 meters and weighing only 600 lb. in firing order. The baseplate was fitted with wheels, and it could be brought into action without dropping the wheels. It was simple to operate, which meant gunners needed little training; cheap to make, making it easily to produce in large numbers, and the ammunition was relatively simple. It was probably the best mortar of the war.

The Soviets, impressed with the power of their 120, spewed out heavier mortars, a 160mm weapon and a 240mm mortar, which could rmch as far as many artillery howitzers and do a lot more damage with their heavy bombs and high rate of fire. The 160 mm could send an 88 lb. bomb to 8,000 yards at a rate of three rounds a minute, while the 240mm fired a 300 lb. bomb every 30 seconds to 12,000 yards.

The Soviets created regiments and brigades of these weapons, which are undoubtedly familiar sights to FitEISE players, and with these, the PPSh 1941, and the DP 28, rolled the Germans back across Europe.

Beyond all this home-produced firepower, the Soviets also benefited from Lend-Lease routes through Persia, the Far East, and the Murmansk convoy run, which brought in all kinds of weapons from Studebaker trucks to P-39 fighters. Also brought in was a considerable quantity of small arms and ammunition. which was put to use.

The Americans provided the Soviet Union with one single MI Garand rifle during the war. It is presumed that this weapon was tested on firing ranges, and did not see combat, but it would be interesting to see what the Soviets thought of the weapon so familiar to the American GI.

Back to Europa Number 58 Table of Contents

Back to Europa List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by GR/D

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com