German Attack

At 4 p.m., Hitler signed "Directive No. 25," and soon mimeograph machines were rolling out the plans for "Operation Punishment." The invasion of Russia was put back four weeks. Italy, Hungary, and Bulgaria would join the assault. Ante Pavelich's Ustaschi would be invited as well. No ultimatum or message would go to Belgrade ... the declaration of war would be served by 250-kilogram bombs from the Luftwaffe's Stukas.

As 27 German divisions massed in four nations for the assault, euphoria swept Serbia. The citizens cheered King Peter 11, sang patriotic songs, and waved flags. They were certain Britain, America, and Russia would come to their aid.

Simovic was not so sure. Already he got word that the Croats were not supporting the coup. He put out feelers to Russia and Britain, asking for supplies and aid. The talks were inconclusive, although he got a "Treaty of Friendship and Non- aggression" with the Soviet Union. He told reporters that Yugoslavia was neither ratifying nor denouncing its agreement with Germany.

Grimly, Simovic ordered the Yugoslavian army of 28 infantry and three cavalry divisions to mobilize, planning to defend every border crossing into the kingdom, a 1,020-mile frontier. On the evening of April 5, Simovic drove to the suburbs for the wedding of his daughter.

The Yugoslavians were still mobilizing at dawn on April 6 (Palm Sunday) when an observation post phoned Belgrade to report 50 bombers heading for the capital. New York Times correspondent Ray Brock saw more than 60 bombers slanting in out of the sun at 7:06 a.m., 30 Ju 87 Stukas peeling off to whack Zemun Airport.

More than 1,500 tons of bombs fell on the city, disintegrating buildings, spreading sheets of flame and clouds of smoke. The Luftwaffe scattered one of their favorite weapons, foot-long incendiary bombs, about three inches in diameter and 2.2 lbs. in weight. When the IB hit the ground or a roof, its magnesium core burst into life, throwing a glittering shower of white, molten splinters in a radius of 10 feet. After a minute it stopped sputtering and began to glow intensely, at about 4,000 F for 10 minutes, before burning itself out. Each bomb came in a cylindrical container called "Molotov's Breadbaskets," with 36 bombs in each container. A single He 111 bomber could carry five of these containers, totaling 180 bombs. Once released, the "breadbasket" burst open at a pre-set altitude, scattering the IBs over a confined area. They could be doused with a sandbag or a shovel of earth. But, as the British had learned, if you threw a bucket of water on a burning incendiary, it would explode and throw burning fragments in all directions.

Incendiaries scattered all over on Belgrade, burning with a blue-white light on the trolley tracks. High-explosive 250-kg bombs detonated, too, adding to the destruction and the din, which was joined by the cadence of church bells, the wail of ambulance sirens, and honking car horns.

All over Belgrade were scenes of horror. One man saw a grocer's delivery van, impressed as an ambulance, piled high with bodies, including a young girl wearing one silver slipper on her right foot. Her left leg had vanished altogether. The Terazia was hit by a bomb that left a 30-foot wide crater full of 300 shredded bodies. A parachute mine hit the Kralja Milana shopping district, just as merchants were raising their shop shutters. After the bomb went off, a body lay in front of every single store, as if arranged by a stage director.

Bombs rained down on the zoo, and sent panic-stricken animals stampeding into the streets. A polar bear, moaning piteously, hobbled towards the Sava River.

The Luftwaffe reached the capital ahead of Simovic, who drove back to his ministry in top hat and tails amid a fearful air attack that was the beginning of two days of continuous bombardment.

By Sunday evening the center of Belgrade was a mass of rubble. Anywhere from 3,000 to 17,000 lay dead. 10,000 buildings were flattened. Simovic evacuated the government to Uzice.

By noon, the cabinet met. Unity fell apart right away. The deputy premier, Vladko Macek, a leading Croatian, resigned to head back to Zagreb and share the sufferings of war with his beloved Croat people. The ministers declared a state of emergency and called on the country to mobilize.

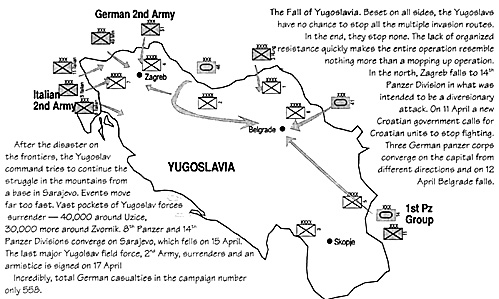

It didn't matter. Nazi tanks blasted through thin Yugoslavian defenses. Panzer divisions snaked in 60-mile long columns. Croatian troops mutinied rather than fight for Serbia. Only five infantry and two cavalry divisions of the whole army actually took the field to fight the Nazis, creaking into battle on oxcarts. Hitler's panzers roared into Greece, cutting the Yugoslavians off from the British. Italian troops stormed into Dalmatia and Ljubljana, Hungarians into the Banat, and three prongs of panzers drove on Belgrade.

"The German soldier answers the traitors," blared the Volkischer Beobachter on April 7. "Our Wehrmacht has begun to deal with the warmongers in the southeast. The fortress of Belgrade has been bombarded." The idea that Belgrade was a fortress would have surprised its citizens.

On April 8, the Yugoslavian cabinet met. It released certain political prisoners, gave salary advances to civil servants in areas threatened by invasion, and withdrew all 10,000-dinar notes from circulation. All pointless decisions.

None mattered. The 14" Panzer Corps drove all the way to Nis. Yugoslavian soldiers had no anti-tank guns, and helplessly hurled hand grenades at Mark III tanks. Snow fell that evening, slowing down the Germans for two days.

Meanwhile Yugoslavia fell apart. The German-speaking minority in Maribor seized public buildings. Two whole regiments went over to the Germans, a third to the Hungarians. Croatian officers welcomed German troops to their bases and officers' messes for some serious drinking. Other troops waved white flags at Luftwaffe aircraft and passively waited to surrender. A German motorcycle company found an entire brigade ready to surrender.

On April 12, the mayor of Belgrade officially surrendered his city to an SS captain who had driven his company ahead of the main column. The government had fled to Pale, a small town in Bosnia just east of Sarajevo, and scrambled for spaces in surviving Yugoslav air force Dornier 17s and Savoia-Marchetti 79s to flee to Greece. The King escaped on April 14, the rest of the government the next day, leaving behind the chief of the general staff, General Kalafatovic, to conclude an armistice. He sent two junior officers under a white flag to ask for truce.

Armistice

The Germans insisted on the signature of a representative of the civilian government. Most of those people were on their way to Athens. The buck was passed to the luckless Cincar-Markovic, who had been disgraced and out of a job since the coup. As the last representative of a Yugoslavian government recognized by the Nazis, he was flown to Belgrade on a Luftwaffe plane. There, 12 days after the invasion, 24 after Yugoslavia signed the Tripartite Pact, Yugoslavia surrendered. Yugoslavian casualties were never worked out, but 254,000 Yugoslavian soldiers found themselves PoWs. 15,000 Yugoslavian soldiers, some small ships, and a squadron of bombers, fled along with the government to Greece and Egypt. King Peter moved to Cairo, then London. German casualties were 151 killed, 558 overall. The victory was bloodless.

Cincar-Markovic was pretty much also the last representative of the Yugoslavian government. As early as April 10, Zagreb radio proclaimed a "free and independent Croatia" under Pavelich, who was still in Rome.

With Yugoslavia prostrate, the Nazis divided the nation. Carinthia became part of the Reich directly. The Germans took over responsibility for occupying Serbia, as it stood astride the Orient Express, which shipped Rumanian oil -- half of Germany's wartime supply -- to the Fatherland. Bulgaria annexed Macedonia. Italy occupied Dalmatia, Slovenia, and Montenegro. Hungary gained the Backa and the Banat, populated by Magyars. Yugoslavia would provide Germany with 60 percent of its bauxite (raw material for aluminum) and a quarter of its copper and antimony.

That left Croatia and Serbia. The former was already a nominal kingdom under the Italian Duke of Spoleto, with Pavelich providing the real political base. He arrived in Croatia with fewer than 100 loyalists, but the Italians provided the muscle. His first move was to organize a political army of 15 battalions, and a Ustaschi Guard of an infantry regiment and a cavalry squadron. Manpower came from conscription, but enough Croatians joined up to fill out three divisions in the Germany army, the 369, 373, and 392; and two SS divisions, the 13th and 23rd Mountain.

In Serbia, the Germans found Gen. Nedic, the former chief of staff of the Royal Yugoslavian Army, pliable enough to form a puppet government. He created a State Guard of five battalions (53,560 men) to defend the rump state. To this was added the Russian Guard Corps, three regiments of 4,000 men, largely of anti-Soviet Russian emigres who had fought in World War I.

As the Wehrmacht's first team pulled out to attack the Soviet Union, the second team moved in to carry out occupation. The Italians deployed 22 divisions into their provinces, while the Germans appointed Field Marshal Wilhelm List to head Armed Forces Command Southeast. Four divisions, 704, 714, 717, and 718, took up occupation duties, the first three in Serbia, the last in Croatia. The officers and NCOs were World War I veterans, and the division lacked motor vehicles and logistical services.

However, what the Germans lacked in firepower, they made up in policy. Their policy was stern, but consistent. Maximum economic exploitation. The Italians, on the other hand, were wavering and inconsistent, doing little to restore the economy of their areas. Worse, Pavelich's Croatian Ustaschi forces carried out vicious massacres of Serbs and members of the Orthodox church, killing between 350,00 and 750,000 of their countrymen.

Soon Yugoslavians were taking to the abundant hills to battle the overlords. The real war in Yugoslavia was about to begin.

WWI to WWII

Back to Europa Number 57 Table of Contents

Back to Europa List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by GR/D

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com