I am prompted to write this as a result of John Astell's EXchange letter in TEM #49. John asserts that the Ist British Airborne Division seized the Italian port of Taranto on 9 September 1943 in an amphibious operation, the follow-up forces landing at the port itself. This put me to thinking as I recalled this was not truly an amphibious operation at all, at least in the Second Front sense of the term. Somewhere in my several hundred books on the Second World War, Operation SLAPSTICK must be covered in some detail. Well, it seems to be one of the more obscure operations of the war, as it did not involve a protracted fight with Axis forces. But what is available contradicts John's thought on how the operation was conducted, and points out a hole in the Europa system.

When the planning for an invasion of Italy began, a large scale amphibious operation was contemplated at Taranto as the planners believed it would catch the Germans off guard, being a bold venture beyond the range of most supporting aircraft. It was ultimately rejected for the very reason it was considered so bold, being beyond the range of Spitfires flying from Sicilian airfields.

Thus the Allies finally settled on Operation AVALANCHE, to occur in the Gulf of Salerno (having rejected all operations north of that location for the same reason as at Taranto).

When the Italian negotiators signed the secret surrender agreement on 3 September 1943, the delegation informed the Allies that few German forces were in the heel of Italy (Apulia) and they were expected to withdraw. Thus the Italians offered to open the ports of Taranto and Brindisi to the Allies, if they could be occupied in conjunction with the announcement of Italy's surrender.

This offer was totally unexpected, and the Allies had no plan to capitalize on it. Admiral Cunningham informed General Eisenhower that if the General could make the troops available, the Navy would provide the ships to transport them. After brief contemplation, Eisenhower agreed to move 1st British Airborne Division (concentrated in two widely separated locations, 400 miles apart in Tunisia) and a limited amount of equipment to secure the port and establish minimal air defense.

Orders were issued on 4 September 1943 to the division's commander, Major General Hopkinson, who happened to be in Sicily investigating future airborne operations for his unit. His unit, the only one immediately available, was to board vessels supplied by the navy to occupy Taranto on or about 11 September.

The ground forces were to embark on four British light cruisers commanded by Commodore W. G. Agnew aboard HMS A urora.

As the days passed, the transportation requirements varied wildly, as no standard loading plans existed for light cruisers. Planning became such a nightmare for the staff, that the operation took on the nickname "Bedlam" due to the rapidly changing conditions. The British added the 2600 ton fast minelayer Abdiel to the transportation fleet. On 7 September ' Hopkinson was ordered to embark his force the next day for a 9 September arrival in Taranto to dock after the departure of the Italian fleet to Malta to surrender.

Even with the addition of the Abdiel, it was feared that some troops of the first echelon would be left behind. Admiral Cunningham appealed to Rear Admiral Davidson, who was leading a column of light cruisers towards Salerno. Davidson agreed to detach a cruiser and at 1914 hours on 7 September, signaled the commanding officer USS Boise "Return at once to Bizerte, report to CINCMED." Boise did so immediately and embarked 788 officers and men, including a curious mixed unit commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Peniakof (Popski's Private Army). Seaplanes were put ashore to make room for 60-70 jeeps stacked in the hanger and on the fantail.

Embarkation was completed on the 8th, the six warships departing Bizerte that evening. The initial echelon comprised the Advanced Division Headquarters, 4th Parachute Brigade, elements of Ist Parachute Brigade, 9th Field Company and "Popski's Private Army". Vice Admiral Power (RN) was directed to provide escort with British battleships Howe and King George V and six destroyers, all sailing from Malta.

As the warships approached Taranto on the afternoon of the 9th, the Italian battleships Doria and Duilio with three cruisers were standing out of the port. The convoy of warships entered Taranto harbor in the early evening. Each ship took on board an Italian harbor pilot to guide them to berths. USS Boise was directed to a mooring by its pilot, but Captain Theboud declined, preferring a berth at the mole. Once docked, Popski's Private Army immediately debarked and moved into the city. The remainder of her passengers followed. Meanwhile, Abdiel moored in the location Boise had declined. Shortly after midnight, while unloading was underway, a contact mine beneath Abdiel exploded and sank the minelayer, killing 48 of her crew and 10 1 soldiers.

There was no enemy opposition to the landing. The cruisers departed Taranto immediately after unloading was completed and returned to Bizerte where the second echelon of the division awaited transport. This consisted of the remainder of the 1st Parachute Brigade, 1st Airlanding Brigade, and the Glider Pilot regiment. These arrived at Taranto aboard the light cruisers on 12 September.

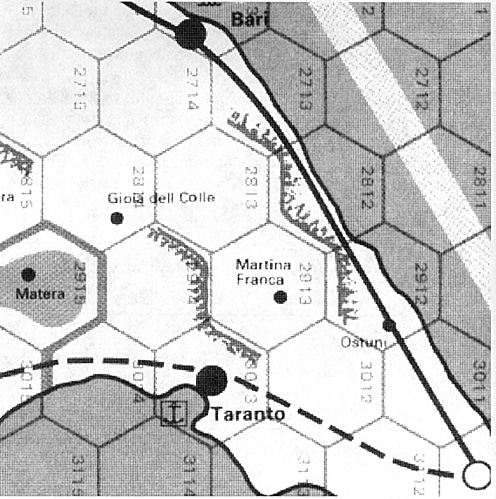

1st (Br) Airborne Division secured Taranto and the airfield at Grottaglie on the 9th. Monopoli and the Adriatic coast were found clear of the Germans the next day. 10th Parachute Battalion had a sharp encounter with Axis troops at Castellonata on the 11th, but other forces entered Brindisi the same day.

This operation is significant in that it outflanked whatever defensive positions the Germans may have planned for the toe and heel of Italy. At little cost, it placed 2 excellent ports in the Allies hands. However, this must be balanced against the tactical immobility of the 1st (Br) Airborne Division, as it was rushed to the scene with virtually no transport assets and little artillery. Due to shipping commitments elsewhere, primarily supporting 5th (US) Army operations at Salerno and 8th (Br) Army operations across the Straits of Messina, no force could be moved immediately to exploit the success of the airborne division.

SLAPSTICK in Europa

Now let's turn to Europa. There are no provisions for a naval task force to transport troops without heavy equipment in Second Front. In this respect, Operation SLAPSTICK cannot be replicated in the system. Naval transport was not used for this operation, therefore using NTs will not satisfy the requirement. Further, this oversight has additional implications for Grand Europa, as warships were used on a number of occasions by the Allies to transport troops (landing in and evacuation of Norway, evacuation of Dunkirk, evacuation of Crete, landing in Taranto to name only a few).

The only way to resolve this issue is to allow a task force to conduct emergency transportation of unsupported units only, at a rate of 2 task force factors to every RE so lifted, but only allowing half of the TF to transport units. Transporting naval strength points cannot fire in combat. Thus a 16 point task force could lift 4 REs of troops, (the size of 1st Airborne Division broken down with its headquarters allowed to be transported in its parachute capacity, without heavy equipment). The remaining factors in the task force would fulfill the role of escort. The TF would fire with a strength of 8. Costs to embark and debark the force are as per those for naval transports, and amphibious landings (in enemy-owned hexes) may not be conducted.

Having proposed a method to allow a landing at Taranto to occur, we must still consider whether such an emergency transport capability should be limited. Naval commanders were loath to use their forces in such a capacity unless it was a true emergency. The only method I can propose to limit its usage is to couple it to the calendar. As a proposal, limit the capability to twice in each half year (I would not propose once a quarter, as I can think of some instances where this sort of transport occurred in rapid succession, Dunkirk and Norway for instance).

Further, I would not limit it to a specific theater of operations, but the entire area of play covered by Europa. A capacity of this type probably is not merely to be limited to the Allies, but should be available to the Soviets and Axis as well.

The other issue is the rules governing Italian surrender. Clearly, Italian troops that go over to the Allies gain control of the facilities (ports, airfields etc.) they occupy. The only method by which Italian forces in Taranto can secure the port is for an Allied unit or units to be within 3 hexes. The rules do not state that these must be land forces, but only land forces can gain and retain control of terrain. Thus I would assume that a land unit aboard naval transport or amphibious units would fulfill the requirements of Rule 38132 (page 58 of the Second Front rules) if it were within 3 hexes of Italian units in Taranto at the time of surrender.

Selected Bibliography

History of the Second World War, The Mediterranean and

Middle East, Volume V, BG C. J. C. Molony, London, 1973.

History of the Second World War, B. H. Liddel Hart,

G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1970.

History of United States Naval Operations in World War II,

Volume IX Sicily - Salerno - Anzio January 43 - June 44, Samuel

Elliot Morison, 1954.

Monty, Master of the Battlefield, 1942-1944, Nigel

Hamilton, Scaptre, 1983.

The Second World War 1939-1945, Army, Airborne

Forces, Lt Col T. B. H. Otway, 1990.

Tug of War, Dominick Graham & Shelford Bidwell, St.

Martins Press, 1986.

U S. Army in World War II, Mediterranean Theater of

Operations, Salerno to Cassino, Martin Blumenson, U. S. Army,

1969.

White Ensign, The British Navy at War, 1939-1945,

Captain S. W. Roskill, United States Naval Institute, 1960.

About the Author

Lieutenant Colonel Cory Manka is a US Army Officer currently assigned to the International Military Staff of the Headquarters, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), in Brussels, Belgium. As a field artilleryman, he has broad experience of artillery operations at the battalion, brigade, division, and corps level. In addition to his current Joint Assignment, he has served a two-year tour in the United Kingdom as an exchange officer at the Royal School of Artillery.

Col. Manka has been an avid wargamer and historian since the age of 12. No stranger to Europa, he has contributed several articles and EXchange items to TEM over the years.

Back to Europa Number 56 Table of Contents

Back to Europa List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by GR/D

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com