Her operators called it the "Pig," but its official name was the

"SLC Human Torpedo," for "slow speed torpedo." She was 6.7 meters

long, 53 centimeters in diameter, and was ridden by two men, a pilot

forward and his assistant astern. Their legs were held in place by

stirrups, and a windscreen was used as a human breakwater. The

maximum speed was 2.5 miles per hour, action range, about 10 miles,

limit of submersion depth 30 meters. The "pig" was driven by an

electrical motor, with a battery of 60-volt capacity. The rudders were

controlled like an airplane. The pilot had a panel of control instruments

which were illuminated so as to be read by night.

Her operators called it the "Pig," but its official name was the

"SLC Human Torpedo," for "slow speed torpedo." She was 6.7 meters

long, 53 centimeters in diameter, and was ridden by two men, a pilot

forward and his assistant astern. Their legs were held in place by

stirrups, and a windscreen was used as a human breakwater. The

maximum speed was 2.5 miles per hour, action range, about 10 miles,

limit of submersion depth 30 meters. The "pig" was driven by an

electrical motor, with a battery of 60-volt capacity. The rudders were

controlled like an airplane. The pilot had a panel of control instruments

which were illuminated so as to be read by night.

The business end of this curious device was a 300-kilogram warhead of explosive at the bow, which could be detached from the rest by an easily manipulated mechanical clutch. After that came the body of the torpedo, the fore trimming tank, the first pilot's seat, the guide and control instruments. Then the batteries, motor compartment, and second man's seat. The assistant leaned his back against a chest containing wire and net-cutters, and clamps used to tie the torpedo to an enemy ship. Behind that came the propeller.

The pilots wore a special diving suit which covered them entirely, which had a six-hour supply of oxygen.

The "pig," in theory, would be clamped to the deck of an Italian fleet submarine, and released near an enemy harbor. The crew would then guide it by luminous compass, usually by night, into the enemy harbor. The co-pilot would use his net-cutters to punch holes in enemy booms. Finally, the crew would reach the target.

A "pig" crewman wrote "You see the outline of your target against the sky. You have dreamed of this moment for months, you have been training for it for years. This is the decisive minute. Success means glory; failure, a unique opportunity lost for ever."

The crew would then pilot their "pig" under the enemy ship, the pilot's assistant would clamp the torpedo to the target, set a two and-a- half hour timer, and the pair would sail away.

Such was the Italian midget submarine. a weapon Italy used with immense courage and panache against the British in Gibraltar, Malta, and Alexandria, knocking out two battleships, earning the admiration of their enemies, and redeeming Italian valor.

First Used

The Italians first used stealth weapons of this sort in World War I, when a doctor and a naval engineer teamed up to sail a tiny torpedo boat into the Austro-Hungarian port of Pola on 31 October, 1918, and sink the massive Austrian battleship Viribus Unitus.

After Benito Mussolini came to power, the Italian Navy continued to experiment on midget submarines, seeing them as a weapon to use against the Royal Navy's huge battleships and carriers. Italy lacked carriers and naval aviation.

In September, 1940, the Italians set up the Training Center of Sea Pioneers at San Leopoldo, near Livorno, to train midget submarine crews. Officers of all arms volunteered and were trained on underwater breathing gear. They were also heavily interrogated to find out why they had volunteered. Applicants who had suffered financial reversals, or love or family quarrels, were bounced out. Extensive medical screening was followed by a personal interview with the unit's commanding officer. Secrecy was absolute.

The first attempt to use "Pigs" came in August 1940, before the school was set up. The submarine 1ride, loaded with three "Pigs," set off to attack Alexandria, where two British battleships and an aircraft carrier were at anchor. However, British torpedo planes caught and sank Iride off Tobruk. Only 14 men survived.

In September, the Italians tried again, with the submarines Gondar and Scire, the latter commanded by Prince Valerio Borghese. The former was to attack Alexandria, the latter Gibraltar. Gondar ran into trouble, an RAF Sunderland and HMAS Stuart. After long depth-charging, Gondar surfaced, her crew abandoned ship, and the sub and its midgets went to the bottom. Amazingly, the submariners kept their mouths shut.

Scire's luck was little better. She was 50 miles from Gibraltar when the Supermarina in Rome radioed that the Royal Navy had left harbor. Scire headed home.

Scire tried again in October 1940, with three Pigs. After several attempts, Borghese penetrated the Straits on 29 October, and entered the Bay of Algeciras. The target was the battleship HMS Barham. After attacking, the Pig crews would flee to neutral Spain. Amid total silence, at I a.m. on 30 October, Borghese released the three Pigs, and headed for Italy. One team found its compass jammed, had its torpedo squashed by water pressure, and its motor broke down. The team headed for Spain to rendezvous with an Italian agent. The second team had problems with its breathing apparatus and also had to abort. The third team's trim pump and batteries didn't work; Lieutenants Gino Birindelli and Damos Paccagnini were determined, but soon Paccagnini began to suffer carbon dioxide poisoning. Birindelli ordered his co-pilot to head for Spain and carried on alone.

Birindelli came within 30 yards of Barham, set his torpedo to explode, and tried to escape to a Spanish ship moored in Gibraltar harbor. The Spaniards tried to hide Birindelli, but when the warhead exploded (doing no damage, but frightening the British), British troops searched all ships in Gibraltar Harbor, and caught Birindelli.

10th Light Flotilla

On 15 March, 1941, the Italians formed the "10th Light Flotilla," the usual nebulous codeword for a highly secret formation. 10th Light Flotilla, better known as Decima Mas, ran all Italian midget submarine and midget torpedo boat operations and their training. Decima Mas sailors were only given information on a need-to-know basis, and secrecy was tight. Crews practiced in La Spezia on the elderly battleship Giulio Cesare. When not practicing, Decima Mas sailors were not allowed to talk in the mess about politics, news, or women. Walls were covered with photographs of Alexandria and Gibraltar harbors instead of pin-ups.

Scire tried again to attack Gibraltar in May 1941. This operation called for the Pig crews to be flown to Spain under false diplomatic papers, and brought aboard the Italian merchant ship Fulgor, interned in Cadiz since the war's outbreak. The crews would thus endure less fatigue and danger from an extended submarine cruise. Scire would join Fulgor, take the operators and their supplies aboard, and enter Gibraltar from Algeciras Bay.

Scire was in position on 23 May, and slid into Cadiz harbor, past merchant ships, reaching the 6,000-ton tanker Fulgor. After handshakes, Borghese showered on Fulgor while the tanker provided the submarine with fresh vegetables and Pig crews.

The two Pig crews were launched late on the 25th, smeared with lanolin. Lt. Decio Catalano's three-man crew paddled off to attack a steamer of medium tonnage. While his crewmen tried to attach their warhead to the target, Subit. Antonio Marceglia lost oxygen and in turn lost consciousness - and the torpedo. SubIt. Licio Visintini did little better, as his torpedo and compass were not ftinctioning properly. The first ship he saw was a fally-lit Red Cross hospital ship. The second was a storage tanker.

As Petty Officer Giovani Magro tried to tie the torpedo to the ship, he too ran out of air, and so did Visintini. They jettisoned their warhead and were able to return to the Fulgor and Italy.

Progress

Italy's midget submarines weren't making much progress - their midget speedboats did no better in a July raid on Malta that ended in failure, killing Moccagetta, the head of Decima Mas. But they did attract the attention of British intelligence, which fori-ned the Underwater Working Party in Gibraltar as a countermeasure.

Borghese replaced Moccagetta, and in September he tried again at Gibraltar. A determined character, he improved the Italian midget submarines, changing everything from boots to warhead, and recruited for more volunteers. He amazingly found highly capable swimmers in such unlikely sources as the Army's alpine troops.

Borghese, still commanding Scire, took the sub back to Gibraltar in September, using the same cast as the previous attempt, and the same procedure. He reached his target on 19 September, dropped off his crews, and left. Intelligence reported two hot targets, a British battleship and aircraft carrier.

Lt. Amadeo Vesco attacked at 12:30 a.m. on 20 September, and sneaked into Gibraltar harbor. He spotted a Nelson-class battleship, but it was too well-guarded, and he had trouble with his breathing set. He tried a merchant ship moored in the roadstead, and successfully fastened his charge to the hull in line with the funnel position, then sailed back to Spain, where his team was picked up by Spanish coastguardsmen. From captivity they saw their target, the 2,444-ton British tanker Fiona Shell, "split in two, slightly astern of the funnel. Her stem disappeared, her bows rising high out of the water" at 7 a.m.

Lt. Decio Catalano couldn't locate an aircraft carrier, but found a large, empty tanker, and moved in. This turned out to be the captured Italian tanker Pollenzo. Catalano didn't want to destroy an Italian ship, so he found a large armed motorship near it -- the British Durham, 10,900 tons -- and set the fuses at 5:16 a.m. At 5:55, he tooled off, and landed in Spain at 7:15 a.m.

"At 9:16," he wrote in his report, "a violent explosion took place at the stem of the motorship I had attacked; a column of water rose to about 30 meters. The motorship settled slowly by the stem, the entire structure of her bows emerging from the water. Four powerful tugs came to her assistance and towed her ashore, with considerable trouble."

Finally, Lt. Visintini's Pig survived an ordeal of depth-charge shocks and patrol boats. He planned to attack a cruiser, but picked a less-guarded tanker, figuring the explosion would do more damage. He detached the warhead and set fuses at 4:40 a.m., and again managed to worm through patrol boats to Spain to meet their Italian contact agent.

At 8:43 a.m., the 15,893-ton tanker Denbydale exploded and sank. 30,000 British tons had been destroyed, and the Italians had escaped to Italy, where they received the Silver Medal for gallantry in war (along with Borghese) from King Victor Emmanuel, who had not known of the operation until it was over. A week after the ceremony, in civilian suit, he visited Decima Mas's training base, and watched an exercise in the pouring rain. He was very impressed, and presented Decima Mas with a wild boar from his estate.

Not so impressed was the Royal Navy, which had to clean up Gibraltar Harbor, and work on their defenses. They did so, and the Italians decided to switch targets from Gibraltar to Alexandria.

By December 1941, Royal Navy fortunes were approaching their lowest. Two battleships (Barham and Prince of Wales), two battlecruisers (Hood and Repulse) and one aircraft carrier (Ark Royal) had been lost, and the war was expanding to the Far East. The Navy was thinly-stretched.

Alexandria

To add to this tension, Decima Mas planned an assault on Alexandria Harbor, where two of the Royal Navy's toughest battleships, Queen ElLabeth and Valiant, were based. If these two ships were out of the game, Britain would literally have no capital ships in the Mediterranean. Italy had five.

Once again, the submarine Scire was tasked with the mission, and three teams were picked. The boss was Lt. Count Luigi Durand de la Penne. Absolute secrecy was maintained, and planning was finely detailed. After laying the mines, the Pig crews were not to return to Scire directly, but beach themselves at a poorly-guarded area, make their way into Alexandria, and then make their way to a rendezvous point with Scire. Borghese's Scire left La Spezia on 3 December, and the Pig crews joined her at Leros on 14 December. Scire headed south, her machinery muffled with blankets to reduce her sound signature.

After a heavy storm on the 16th, Scire sailed through mined waters and surfaced at 6:40 p.m. just off Alexandria harbor. Borghese was amazed to be right on target, right on time. His three attack teams prepared their Pigs, and got underway.

De La Penne's target was Valiant. He and his co-pilot, Petty Officer Emilio Bianchi, motored off just below the surface through the boom defenses. De La Penne could hear British guards at the end of the pier talking and saw a PT boat cruising around, dropping depth charges.

Next, he cruised on the surface over Valiant's torpedo net' approaching the 32,000-ton dreadnought. De La Penne's suit was leaking and he didn't know how much longer he could hold out. At 2:19 a.m., he was 30 meters from the hull. When he touched it, his Pig took on extra weight and dropped to the bottom, tossing Bianchi into the harbor.

De La Penne dived to the bottom and tried to start his Pig's engine to get it underneath the hull, but it didn't start ... a steel wire was entangled in the propeller. Using all his strength, he dragged the craft, making a superhuman effort to pull it under Valiant. With his last vestiges of strength, goggles fogged, he set the fuses to go off at 6 a.m.

Then De La Penne swam up to the surface, away from the ship .... and was picked out by a British searchlight. Defeated, he climbed onto Valiant's mooring buoy to await capture, and found Bianchi, who, after fainting, had risen to the surface like a balloon and so on regaining consciousness hid himself on the buoy to avoid causing an alarm.

At 3:30 a.m., the two were hauled aboard Valiant and interrogated by a British officer. The two Italians handed over their Navy ID cards, making it clear they were military men, not spies, and refused to answer questions. The British took them ashore to be interrogated, but the Italians refused. So the British took them back to Valiant at 4 a.m., a busy morning for the whaleboat crews.

Valiant's Capt. Charles Morgan had not achieved command of a battleship by being a fool, and he deduced that De La Penne and Bianchi were midget submarine crews. He demanded to know where the charge was located. No dice. Morgan shrewdly had them placed between the two gun turrets below, figuring that proximity to the mine would loosen their tongues.

De La Penne sat quietly until 10 minutes before the explosion, then asked if he could speak to Morgan. "I was taken aft, into his presence," De La Penne wrote. "I told him that in a few minutes his ship would blow up, that there was nothing he could do about it and that, if he wished, he could still get his crew into a place of safety. He again asked me where I had placed the charge and as I did not reply he had me escorted back into the hold."

But Morgan pulled the alarm rattler anyway, and Valiant's sailors trooped up topside. A few minutes later, the explosion came. "The vessel reared, with extreme violence. All the lights went out and the hold became filled with smoke. I was surrounded by shackles which had been hanging from the ceiling and had now fallen. I was unhurt, except for pain in a knee, which had been grazed by one of the shackles in its fall."

Valiant listed four degrees to port, and hit the harbor's shallow bottom. De La Penne and Bianchi were taken ashore to a PoW camp.

Meanwhile, Engineer Capt. Antonio Marceglia and PO Spartaco Schergat had an easier time, pursuing Queen Elizabeth. They sailed in through open net gates, to their surprise, and "in no time at all I found myself face to face with the whole massive bulk of my target," Marceglia wrote. He laid his mine at 3:15 a.m., battling the water's intense cold. Marceglia sailed off, his teeth chattering, and landed on the beach at 4:30 am. Marceglia and Schergat, posing as French Sailors, wandered round Alexandria for some time, until they made their way to the train station to get to their rendezvous point at Rosetta. There they spent the night in a squalid little inn, but the English currency they had was the wrong variety, and attracted attention. Soon Egyptian police picked up the pair and turned them over to the Royal Navy.

Their bomb worked. As De La Penne and Bianchi were waiting to debark from Valiant, they saw Queen Elizabeth rise out of the water and fragments of iron and other objects fly out of her funnel. The immense ship drifted to the bottom of Alexandria harbor.

The last pair, Capt. Vincenzo Martellotta and Petty Officer Mario Merion, were to attack an aircraft carrier reported in harbor. Martellotta had no luck ... his Pig took a lot of shocks from depthcharges. Then it rammed a marker buoy, having been driven against it by a passing destroyer. When he finally entered Alexandria, there was no sign of any carriers, but he spotted a 16,000-ton tanker, and figured that was good enough.

He and Marino set their weapon and fuse at 2:55 am, and got ashore with no further incident. Once ashore, they were stopped at a control point by Egyptian customs officials, who summoned the Royal Marines. They took the pair in custody.

Martellotta and Marino were being interrogated (to no avail) at 5:54 am, when a violent explosion was heard, which shook the building. That blast was followed by two more.

Strategic Victory

It was the greatest victory of the Italian Navy in the entire war. Valiant and Queen Elizabeth were both out of the game for months, at a cost of six men captured. The Italian Navy had crushing superiority in the Mediterranean and could resume supplying Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps with impunity. In fact, had Italy's Supermarina been less timid (or so insisted Valerio Borghese) it could have launched the planned invasion of Malta. But neither the Italian nor the German high commands grasped the real potential of seapower, and the glittering chance passed. Italy controlled the Mediterranean, but did nothing with it.

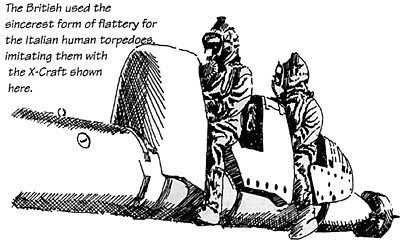

Perhaps they were fooled by the British. They only admitted the loss of the tanker and that both battleships were damaged. As they had not sunk deeply in harbor, they did not appear damaged. The two ships maintained battle-ready appearances - steam was kept up, bands played on the quarterdeck, and Valiant even hosted a reception - and it was not for months that the two dreadnoughts were pulled out of the water. Queen Elizabeth spent even more months in a floating drydock. But the British were most impressed with Italian valor. Winston Churchill minuted his chief of staff, General Sir Hastings Ismay, "Please report what is being done to emulate the exploits of the Italians in Alexandria Harbor and similar methods of this kind." By the middle of 1942, Churchill had his answer: X-Craft, the famous British midget submarines, that put the Nazi superbattleship Tirpitz out of business.

Meanwhile the war went on. All six Pig crewmen on the Alexandria raid spent the next two years in an Allied PoW camp, writing their reports. Borghese yielded command of Scire to devote all his energies to Decima Mas, as chief of the underwater department. Decima Mas hurled its torpedo boats at Malta and dispatched 10 speedboats to the Crimea, to help Germany defeat the Sevastopol fortress. Soviet ships were running supplies into the fort by night, speedboats were brought in to sink them.

The Germans were highly impressed by Decima Mas, and sent naval officers to study their operations. Borghese found the Germans far behind in developing midget submarines and warheads, but that they had superior incendiary devices and fake documents.

In May, Queen Elizabeth was in the floating dock at Alexandria. Three Pigs were sent in, but all three had to abandon their craft under heavy depth-charging. The feat of December could not be repeated.

On 10 August, the Scire, Italy's sole submarine for carrying Pigs, was sunk off Haifa. Her 50 crewmen and 10 Pig operators drowned.

By now, Borghese was focused again on Gibraltar. The Italians now came up with an ingenious plan. The Villa Carmela in Algeciras was a waterfront Spanish villa rented by Italian expatriate Antonio Ramognino. The villa was a mere half mile from Gibraltar by sea. This house stood near the beached and scuttled Italian 4,900-ton tanker Olterra. When Italy entered the war, the crew had scuttled their ship, leaving most of it above water and certainly immobile.

Borghese and Vinsintini hit on the idea of using the stranded tanker as a base for Pig boats. Engineers were sent, ostensibly to repair 01terra, but actually to cut a section five feet wide from the steel bulkhead separating the bow compartment from the cargo hold and hinging it such that it could swing open like a flap. Then the flooded forward tanks were pumped out until the bows rose out of the water, allowing a four-foot hinged door to be cut in the side of the ship, opening into the bow compartment about six feet below the waterline.

When the ship returned to her former position, the hold was dry and the bow compartment flooded. Pigs, assembled in the hold, could be lowered into the bow compartment, and could then pass out of the ship through the hinged flap six feet below the water.

Borghese ingeniously shipped the torpedoes in pieces under Italian Foreign Ministry seal to the Italian consul in Algeciras. To obtain the seal in the normal way would have leaked the plans to the indecisive Mussolini or British intelligence, so Borghese had some of his men burgle the Foreign Office by night, make off with the stamp, and mark the critical boxes. The Foreign Minister, playboy Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini's son-in-law, was unaware that his office had been burgled by his own Navy.

The villa became the storehouse for explosives and spare parts, as well as a dormitory for the operation. Crewmen assigned to Olterra (which was moored under the noses of the British consulate) were trained in merchant ship deck technique, slang, etiquette, even the proper way to spit like a merchant seaman.

Spanish guards ignored these Italians, who wore long beards and chased Algeciras prostitutes like Olterra's real crew.

Attack

On 13 July, Italian swimmers set out from the villa to attack various ships, each swimmer carrying his own mines on containers on his back and chest. Each mine weighed 5 lbs., enough to blow a four-foot hole in ship plates. Despite British efforts, four ships totaling 9,468 tons were damaged. All swimmers returned to Spain.

15 September, and swimmers tried again, sinking the British steamer Raven's Point, 1,787 tons.

Late on 7 December Visintini, by now a veteran Pig operator, led three human torpedoes into Gibraltar Harbor, which was packed with the battleships Rodney and Nelson, two carriers, Formidable and Furious, and American troopships, loaded with reinforcements for the invasion of French North Africa. "The craft are ready and the charges are fused," he wrote in his diary. "The three torpedoes stand in line: they look like three tiny, but powerful ships of war. We are going to sea and whatever happens, we are determined to sell our skins at a very high price."

But the British were alert, and picked up the advancing Pigs at I I p.m. The base went to full alert. PT boats lobbed depth charges in all directions. The first team was critically damaged by depth charges dropped on suspicion, and its two-man crew captured. The second was machine gunned, and the co-pilot killed, the pilot returned home alone. The third team, Visintini's, practically reached their target when depth charges killed them. Visintini and Magro's bodies washed ashore and were buried at sea with naval honors.

The British were impressed, but did not suspect Olterra. But despite these heroics, Italy was losing the war. Allied troops were in French North Africa, squeezing Rommel. Italy converted the submarine Ambra to carry pigs, and sent it to Algiers with Pigs and attack swimmers.

On 12 December, Ambra released her attack force amid six steamers. Lt. Giorgio Badessi tried five times to attack a target, failed, destroyed his craft, and surrendered to a French sentry. Lt. Guido Arena battled a splitting headache and fastened mines on one of his targets. He too had to beach his craft and surrender, this time to Scottish troops. Midshipman Giorgio Reggiloi and Petty Officer Colombo Pamolli laid mines on a 10,000-ton tanker and a 10,000ton motor ship, also couldn't find their way back to Ambra, and went ashore to surrender.

The swimmers also laid their charges and were also forced to surrender. They sunk steamers Ocean Vanquisher (7,174 tons) and Berta (1,493) and damaged two ships, Empire Centaur (7,041 tons) Armatlan (4,587) - in all 20,295 tons put out of action.

Olterra made another attack on 8 May, using newly-delivered men and equipment. Three teams attacked, under Lt. Cdr. Ernesto Notari. This time the crews met with heavy defenses. Lt. Camillo Tadini had to try six times to plant his mines. After a night of exhausting toil, three steamers blew up, the American Liberty Ship Pat Harrison (7,000 tons), the British Mahsud (7,500 tons), and the Camerata (4,875 tons). The British were infuriated and stupefied.

Despite these setbacks, Allied victory rolled on. British and American troops invaded Sicily on 10 July, 1943. Decima Mas was given a gold medal the month before, but the force was running out of time and ideas. Swimmers were sent to neutral ports to be based out of interned steamers, sinking three ships. Ambra was sent with three speedboats to attack the Allied-held Sicilian port of Syracuse. She was sunk just outside of the harbor.

One Last Attack

Mussolini fell power on 25 July, and Italy's war effort began to disintegrate, but not before one more attack on the night of 3 August, by three Pigs from Ollerra. Lt. Cdr. Notari sneaked into Gibraltar harbor and three ships were sunk: the 7,000-ton Liberty ship Harrison Grey Otis; the 6,000-ton British cargo ship Stanridge; and the I 0,000-ton Norwegian tanker Thoshovdi. Notari, who attacked Otis, ran into trouble when his co-pilot, Giannoli, developed oxygen poisoning, and was forced to leave the craft, which immediately went out of control.

Notari held on while the Pig fell 112 feet. At last the Pig turned upwards, but only to make a wild dash for the surface, still out of control. Notari's Pig nearly hit the bottom of Otis, but he missed it by half a yard. All Notari could do now was sail home on the surface. Incredibly, he was surrounded by a school of porpoises, which swam with him all the way back to Algeciras, which confused British radar operators.

Giannoli landed on Otis's rudder, and was captured. He was transferring from Otis to shore when his mine went off, severely wounding Giannoli's American guard.

That feat ended Olterra's war. Decima Mas planned new attacks on Gibraltar, and even to use a midget submarine against New York harbor in December 1943, but in September of that year, Italy surrendered and switched sides. Decima Mas didn't. Borghese, a loyal Fascist and a charismatic leader, kept his unit on Mussolini's side, and it rallied to the puppet Italian Socialist Republic that Hitler created with Mussolini as the figurehead dictator. Decima Mas's highly-motivated and well-trained frogmen, swimmers, and midget submarine pilots became a ferocious brigade of naval infantry, used against pro-Allied Italian partisans, massacring civilians.

As the war rumbled on and turned more and more against Hitler, Borghese tried to offer feelers to the Allies in which his Decima Mas brigade would cover an Allied invasion of Istria to prevent the Communist Yugoslav partisans from invading the province.

Instead, when the war ended, Borghese stood trial in an Italian court for war crimes, and did a prison term.

De La Penne and other Italian Pig crews did better. They assisted British midget submariners in immobilizing two Italian cruisers being operated by the Germans, Gorizia and Bolzano.

After this feat, De La Penne was involved in clearing harbors that had been demolished and mined by German forces during their retreat. In March 1945, paperwork finally caught up with De La Perme, and he was awarded Italy's Medaglio D'Orio, that nation's highest decoration, for his attack on Valiant in 194 1.

At the ceremony, Morgan, now an admiral and a knight, took the medal himself and pinned it on the uniform of the man who had sunk his battleship four years before.

It was a chivalrous note upon which to end the career of Italy's most daring operations of World War II.

Back to Europa Number 56 Table of Contents

Back to Europa List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by GR/D

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com