One of the common approaches to categorizing warfighting methods is to define the categories of maneuver warfare and attrition warfare. Maneuver warfare is a means to an end, that is, the primary focus of maneuver warfare is to obtain a position of friendly forces with respect to enemy forces such that the end objective is easily obtained. Sometimes the end result is a geographical location, but maneuver warfare may also be used as a method of destroying the enemy's field forces by gaining an advantageous position from which to initiate a battle. Many of the reputations of the great military captains of modem history are based on their use of maneuver warfare in such a fashion. The early campaigns of Napoleon, Lee's campaigns in Virginia in 1862-1863, and in World War Two, O'Connor's offensive in the Western Desert in 1940 and Manstein's campaigns in France (executed by Guderian) and Russia are all sterling examples of using maneuver warfare.

One of the common approaches to categorizing warfighting methods is to define the categories of maneuver warfare and attrition warfare. Maneuver warfare is a means to an end, that is, the primary focus of maneuver warfare is to obtain a position of friendly forces with respect to enemy forces such that the end objective is easily obtained. Sometimes the end result is a geographical location, but maneuver warfare may also be used as a method of destroying the enemy's field forces by gaining an advantageous position from which to initiate a battle. Many of the reputations of the great military captains of modem history are based on their use of maneuver warfare in such a fashion. The early campaigns of Napoleon, Lee's campaigns in Virginia in 1862-1863, and in World War Two, O'Connor's offensive in the Western Desert in 1940 and Manstein's campaigns in France (executed by Guderian) and Russia are all sterling examples of using maneuver warfare.

There are times, however, when maneuver warfare cannot be applied. The foremost example of this was World War One on the Western Front for the first three years of the war where the combination of enormous national armies, narrow frontage and weapon technology development (i.e., effective control of indirect artillery fire and automatic weapons) resulted in the inability to use maneuver warfare effectively at both the tactical and operational levels. The result in World War One, as well as in any war when maneuver warfare is not possible or desired, was the adoption of attrition warfare.

The focus of attrition warfare is to force an exchange ratio of casualties that is acceptable to the friendly side. If the friendly side has a logistical advantage, this means that the exchange ratio need not be numerically favorable to the friendly side to be acceptable. Successful practitioners of attrition warfare tend to get unattractive nicknames ("Grant the Butcher," etc.) and in general are not as highly regarded as the practitioners of maneuver warfare. However, attrition warfare is an attractive option to the logistically favored side in war in that it is a method that can be managed almost as an accounting operation, with victory guaranteed as long as willingness to pay the price to finish the job (read: morale) remains. Maneuver warfare by its nature is less amenable to analysis, and its outcomes are far less certain.

The strategic plans, organization, and doctrine of the pre-WW2 United States army resulted in a real contradiction, well documented in Weigley's excellent Eisenhower's Lieutenants. That is; the US Army's organization, equipment, and doctrine at the tactical levels were based on maneuver warfare. However, the top level strategic planning was based on attrition warfare. David Eisenhower's Eisenhower at War confirms Eisenhower's view of attrition warfare as both acceptable and necessary. A consistent pattern of an attrition warfare phase is evident in all major campaigns under Eisenhower's direction; North Africa in late 1942 through early 1943, several times in Italy, and several times in France and Germany (pre-breakout Normandy and the winter Westwall campaign). In all of these cases, the Axis was weakened by attrition warfare to the point where an Allied breakthrough resulted in a transition to maneuver warfare.

What does this have to do with Europa? Does the Europa combat system model both attrition and maneuver warfare? If not, which one does it model? I would say the answer lies in the range of combat outcomes defined by the ground CRT. Most ground combat of significance in Europa is resolved on the odds columns from 1:1 to 6:1, inclusive. If we count the number of outcomes that result in casualties to the defender (which is of interest to the player who wants attrition) on the unmodified 1-6 outcomes, there are 17 desired results of the 42 possible outcomes. There are 28 outcomes that result in the defender losing the hex, so the loss of the hex is 65% more likely than losses and casualties. Consider the effects of die roll mods by adding in 1:1 (+2) and 1.5:1 (+2) columns, accepting the assumption that the attacker will not use those 1:1 and 1.5:1 columns often if he has a negative DRM, and consider that a DRM on the other columns in most cases is exactly equivalent to a shift to another column. Then there are 22 outcomes with defender casualties and 35 with loss of the hex, so the loss of the hex alone is still 59% more likely.

Based on the above, the fact that all defender casualty losses on the CRT automatically result in territorial losses, and that no defender casualties are possible without territorial losses (at least without the presence of the very limited number of political police units), I contend that the Europa combat system best models maneuver warfare.

Based on this, I think that it is very clear why the Desert games and Fire in the East are consistently the most played and most popular games in the system. Those situations are the ones that highlight maneuver warfare by at least one side without the scenario being hopelessly one-sided as in First to Fight. The combat system works best in those games because they emphasize maneuver warfare, and therefore the games themselves work best. The historical campaign in Italy and the ETO in 1943-1945, however, was primarily conducted as attrition warfare, and my Second Front playtesting experience has convinced me that the evolving play of that game would proceed more smoothly with an attrition warfare model added to Europa.

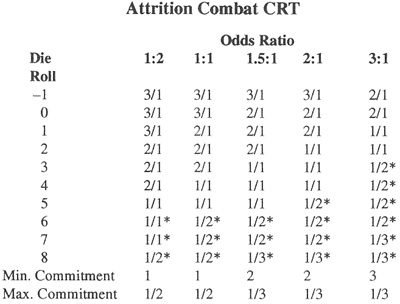

I believe that an attrition model is easy to implement by adding a separate Attrition Combat (AC) CRT as shown above. The AC CRT has no odds ratio columns below 1:2 (the assumption is that no attacks will be voluntarily made in attrition warfare at those odds), and no columns above 3:1 ( the assumption here is that odds beyond 3:1 are such that the attrition phase would be over quickly and that maneuver warfare would dominate at the Europa time scale).

To use the AC CRT, the following rules section must be added:

9A3 (addition). At the instant that an attack is announced, the attacker determines whether the standard or the attrition CRT will be used to resolve the attack. This determination is based on the following:

- 1) the attacker may choose which table will be used if the defender is

in a fort, Westwall hex, Maginot Line hex or ouvrage, a coastal

fortification, fortress, or behind a fortified hexside.

2) the attacker may choose which table will be used if all attacking units are in any or all of the above.

3) the attacker may choose which table will be used if he has more REs of c/m units in the combat than the defender. Selecting the AC CRT in this case triggers required losses for armor.

4) the standard CRT is used in all other cases.

In all cases the AC CRT may be used only if the odds at the moment of combat (i.e., after modification for ground support, naval bombardment, etc.) are between 1:2 and 3:1. If the AC CRT is used, the defender announces immediately prior to the die roll what level of force, in strength points, will be committed. Commitment does not effect the odds ratio, use of AEC or ATEC or their ratios, naval gunfire, or ground support.

The minimum number of strength points he must commit is listed in the Min. Commitment row at the bottom of the appropriate odds ratio column in the AC CRT If there are fewer strength points in the hex, then all must be committed. The maximum that can be committed is the total number of strength points in the hex, multiplied by the fraction in the Max. Commitment row, rounding fractions normally.

9A4 (addition). If the AC CRT is used, the defender loses the number of strength points he committed prior to the die roll multiplied by the number to the right of the slash. The attacker loses a number of strength points equal to the number of strength points committed by the defender multiplied by the number to the left of the slash. If the combat result shows an asterisk (*), and the defender is in a fort, behind a fortified hexside, or in any kind of printed fortification or fortification counter except a fortress, Westwall, or Maginot Line hex, the fort or fortification is destroyed and removed from the map or (in the case of printed fortifications) no longer considered to be present. All normal AEC, ATEC, and engineer die roll modifications are treated normally when using the AC CRT

9B9 (addition). If the AC CRT is used, the attacker may not advance into the defending hex after combat unless all defending units have been eliminated during the combat. Overruns during the exploitation phase may still occur normally.

Back to Europa Number 38/39 Table of Contents

Back to Europa List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by GR/D

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com