In the early months of World War II, the Allied High Command

devised a plan to defeat Germany in a bold, decisive stroke--by

attacking the Soviet Union.

In the early months of World War II, the Allied High Command

devised a plan to defeat Germany in a bold, decisive stroke--by

attacking the Soviet Union.

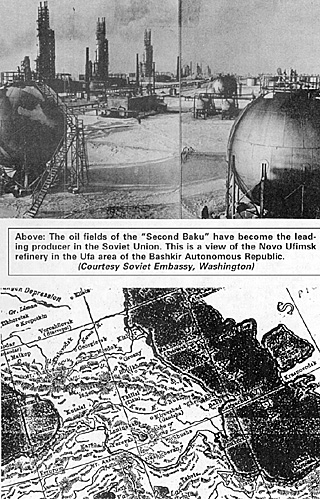

The oil fields of the "Second Baku" have become the leading producer in the Soviet Union. This is a view of the Novo Ufimsk refinery in the Ufa area of the Bashkir Autonomous Republic. (Courtesy Soviet Embassy, Washington)

The "Phoney War" of late 1939 and early 1940 gave Allied strategists plenty of time to ponder indirect approaches to the defeat of Germany. British and French planners identified not one but two vulnerable commodities in the German economy--iron ore and oil.

For her iron ore supplies, Germany depended on the Swedish mines at Lulea. Ore from Lulea traveled by rail to the Norwegian port of Narvik. From Narvik, sea transport moved the iron south along the Norwegian coast to Germany. The Allies' attempt at blocking the flow of Swedish iron ore to German ports is well known.

It started with Allied plans to mine Norwegian coastal waters, evolved into the April, 1940 landing, and ended with the withdrawal of the British and French expeditionary forces from Narvik in early June.

Less known than the Norwegian episode are the early Allied plans to hinder Hitler's oil supplies. Later in the war, Rumanian oil received much attention from the Allies, but in 1940 another prime source of oil for the German economy was her ally, the Soviet Union.

As early as January 19, 1940 the French premier, Edouard Daladier, asked General Maurice Gamelin, the Allied Supreme Commander in France, and Admiral Jean Darlan, the French naval commander, to "work out a memorandum on a possible intervention to destroy the Russian oil fields."

It may seem incredible now that the Allies could have conceived an attack on the Soviet Union as in their interests. At the time, though, the Soviet oil fields looked like a key to success.

Gamelin and Darlan submitted their report on February 22. It stated, "an operation against the Russian oil industry would make it possible to strike a heavy, if not decisive blow against the military and economic organization of the Soviet Union." The report even raised the possibility that the destruction of the fields could push the Soviet Union to the brink of "total collapse." The Allies began developing more detailed plans for the operation, centering on the destruction of Batumi and particularly Baku.

These plans probably became known to the Soviets fairly quickly. On March 6, Kliment Voroshilov, People's Commissar for Defense, publicly visited the Caucasus and Caspian Sea region. At the same time the Soviets began transferring military units into the area. It is even possible that evidence of the Allied threat to the Caucasus played a part in the hastily arranged Russo-Finnish treaty that ended the Winter War on March 12.

On March 14, Turkish sources informed the French that the Soviets had retained a group of American petroleum experts to determine possible effects of bombing raids on the Baku oil fields. The Americans were also to advise how the Soviets could combat the fires resulting from such an event.

Events were developing quickly on the Allied side, also. A three-way conference between Britain, France, and Turkey began on March 15. Representatives of those nations discussed many issues, among them how best to respond to possible German or Soviet moves into the Balkans, and how the Allies should aid in the buildup of the Turkish armed forces.

Presumably, they also discussed the raids on the oil fields-specifically the Allied use of the Turkish airfield at Cizre for the duration of the operations against the Caucasus. French and British air staffs stayed on at Aleppo after the conference with the Turks was finished. They met on March 20 to develop their plans for attack.

One of the first Allied priorities was intelligence, and for this the RAF turned to Sidney Cotton, an Australian aerial photography expert. Cotton had performed reconnaissance missions for the British over western Germany, Libya, and Somaliland before the outbreak of the war, sometimes in a quite daring manner. Three days later, Cotton and the Air Department of MI6 dispatched a civilian Lockheed 12A aircraft from Heston, England. Hugh MacPhail, a personal assistant of Cotton, piloted the plane through Malta and Cairo to the RAF air base at Habbaniya, Iraq, not far from Baghdad.

On March 30, MacPhail took off for Baku accompanied by three RAF personnel. Their flight crossed northern Iran and approached Baku from the Caspian Sea. The Lockheed circled the oil fields and refineries for over an hour at 23,000 feet, with no interference from the Soviets.

The photography completed, MacPhail turned for home and reached Habbaniya ten hours after takeoff.

MacPhail was airborne again on April 3, this time heading for Batumi. Batumi was particularly important as a seaport and as the terminus for an oil pipeline from Baku. The Lockheed overflew Turkey and approached the target over the Black Sea. This time the mission met opposition. Just after exposing the last of their film, Soviet antiaircraft batteries opened fire. MacPhail dove his Lockheed into clouds and successfully evaded the flak. Again they returned safely to Habbaniya.

The film was sped back to Cotton in England and quickly analyzed. The Allies finalized their plans. The primary targets would be storage tanks and refineries. Baku had 67 different refineries, Grozny owned 43, and Batumi another 12--a total of 122. Nine squadrons of Allied bombers would participate in the raids.

The French Armee de l'Air would fly from Cizre, in southeastern Turkey, operating two squadrons of Farman 221 long range bombers, and four squadrons of American built Glenn Martin 167s. The French would primarily deal with Batumi. The RAF would attack Baku and Grozny with three squadrons of Wellingtons flying from Mosul, Iraq. The date was set for June 21, 1940 and the operation was expected to last from 10 to 45 days.

Of course, the German invasion of the West on May 10 changed everything. The disastrous Allied defeats of May and June relegated adventures like the Caucasus raids to the file cabinets, but the story was not quite closed.

Even though never carried out, the Allied plans for the bombing of the Caucasus would have influence on the war. An incident late in the French campaign ensured this.

By Sunday, June 16, the French front had collapsed for the last time. Fleeing French transport trains were jammed in disarray in front of the Loire River, prevented from crossing south by German bombing of the Loire bridges. Many of the trains were simply abandoned. In one, near St. Chariti, German scouting parties discovered carloads of documents from the French General Staff. Included in the papers were the complete Allied plan of the attack against the Caucasus, including copies of the actual reconnaissance photos of Batumi and Baku taken by MacPhail almost three months before.

The Germans forwarded the documents to the Soviets soon after their seizure. The captured plans surely erased any doubts the Soviets may have had about Allied intentions. Stalin's knowledge of the operation suggests one more reason for the high degree of mistrust he showed for the British throughout the war.

In The Air War, 1939-1945, Janus Piekalkiewicz suggests that the apparent British willingness to attack the Soviet Union as shown by the captured plans of the Caucasus raids may also have provided some motivation for the ill-fated flight of Rudolph Hess.

Hess flew to Scotland with his bizarre "peace offer" in May, 1941, only one month before the opening of the German invasion of the Soviet Union.

Most post-war writing is silent on the subject of attacking the Soviet Union. The Germans would launch their invasion of Russia only a year after the proposed attack, and the Russians would become Britain's only ally. Few would admit that they almost went to war with the Soviet Union only a year before Hitler himself invaded. This was especially true in the tense atmosphere of post-war east-west relationships. The British official history does not mention the plans at all, although it discusses other subjects of the March talks with the Turks in some detail.

For example, Churchill, in The Gathering Storm, describes part of the meeting of the Supreme War Council in London, March 28. The meeting took place only two days before MacPhail took off on his first reconnaissance flight. Churchill, at that time First Lord of the Admiralty, uses somewhat cryptic terms: "[Chamberlain] unfolded with precision the case for intercepting the German iron-ore supplies from Sweden. He dealt also with the Rumanian and Baku oil fields, which ought to be denied to Germany, if possible by diplomacy. I listened to this powerful argument with increasing pleasure..."

Writing only three years after the war's end, Churchill obviously had to use care in describing the consideration of a British attack on their later ally, the Soviet Union. It is hard to imagine what diplomatic means the Allies might have possessed in the spring of 1940 that could have succeeded where the Allied diplomacy of August 1939 had so utterly failed.

If the French campaign had been less disastrous for the Allies the attacks on the Caucasus could have been launched. Could the plan have worked? Could less than 200 Allied bombers have brought the Soviet economy to a halt? Even if this were possible, could destroying the Caucasus oil fields have affected the German military might?

Looking at the operation itself, the Allies faced the challenging prospects of operating on a logistical shoestring in Turkey and northern Iraq. As planned, the operation was not to be an extended campaign--the Allies hoped to destroy the targets with only a few raids. The French even expected to get away with no losses.

Logistics problems would have been compounded by Italy's entry into the war on June 10, but Mussolini's declaration of war was prompted by some of the same events that ensured the cancellation of the Allied operation--decisive German victories in northern France. Easing the situation was the proximity to fuel sources; major refineries were located in Haifa, Palestine and Abadan, Iran. Without opposition in the Mediterranean and African fronts, the Allies could probably have sustained an operation of the planned scale for some time.

The distance of the proposed targets from Allied air bases also posed a problem. One estimate states the Allied force could have delivered only 70 metric tons of bombs per mission.

In the Allies' favor was the state of the opposition. In June of 1940 the Red Air Force was still the same organization that had been stymied by the Finns. In addition, the Soviets did not have radar. Throughout the war, radar provided the key element in the successful defense against enemy bombers. The Soviets would have had to rely on crude listening devices, on agents in Turkey and Iraq, or on naval forces in the Black and Caspian Seas to provide early warning of Allied raids. These measures would have taken time to develop. The only alternative to this was standing patrols at high altitude, somewhat questionable as an effective means of defense. The most important part of the Soviet defense would probably have been antiaircraft guns.

The Soviets would have been completely unprepared to deal with night raids. If initial raids succeeded in starting large fires, as it was hoped, night navigation to the targets would have been eased.

In a strategic sense, it is difficult to guess how the Russian leadership would have responded militarily. The Turks were considered capable of containing a Soviet move into that country. One British fear was that the Soviets would seize northern Afghanistan. From there, the cities in northern India would be within range of Russian bombers. India had almost no air defenses.

The most serious counter would have been a Soviet move into Persia, threatening the Anglo-Iranian oil fields and the Iraqi oil fields at Kirkuk.

It is tempting to try and extrapolate the results of later massive American and British bombing of German oil resources, mainly Ploesti and the synthetic fuel plants, to predict results of a small force of mid-1930s vintage airplanes flying against the Caucasus. Such an attempt will obviously lead to prediction of complete failure. Such an estimate would be in line with history; prior predictions of strategic bombing effects have always overestimated the results that would be achieved from the bombing.

The American consultants hired by the Soviets reached a far more serious conclusion on the effects of bombing on the Baku fields.

Piekalkiewicz states: "Allegedly the US experts replied that, given the output of the oil fields so far, the ground must be so saturated with oil that a blaze would be bound to spread instantly to the entire neighboring region; it would be months before the fire could be put out, and years before oil production could be resumed."

Although this could certainly be an honest answer, it is easy to question the motivation of the US experts in giving it. A gloomy out-look such as the one the Americans gave could have resulted in new consulting business on how to implement some sort of damage control or fire fighting at the fields. Answering that fires could be easily controlled and that damage would be minimal would not. Economically, the Allied High Command was probably overestimating the short-term effect of Soviet oil on the German economy. This is somewhat understandable since Allied strategists desperately wished for some "magic bullet."

In their planning scenarios the Allies were always haunted by the specter of a replay of the Great War's stalemate on the Western Front. At times, it seems any plan for defeating Germany with an indirect approach was looked on with favor. Defeating Germany by economic means such as interdicting iron and oil was always an attractive option.

Soviet oil could not have been immediately decisive against the Germans in the way the Allies wished. Only a year later, Hitler voluntarily forfeited the Caucasus oil when Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Although they assumed it would be available again after a quick campaign, Germany maintained an impressive effort for almost four years without it.

To be effective at all, denial of the Rumanian oil fields would have had to accompany the destruction of the Caucasus oil. It is unlikely that any sort of diplomacy could have reduced Rumanian oil shipments to Germany. No adequate bases existed to launch similar bombing raids against Ploesti. Even had bases been available (in Greece for example), Ploesti would have soon been guarded by the Luftwaffe's fighters and flak. That would have provided an insurmountable obstacle for the 1940 Allies.

It is remotely possible that the British had other means against Ploesti available. In 1940 it was actually British petroleum companies that were still running the Ploesti oil fields. It is unknown what covert options were open to British intelligence that might have reduced Rumanian oil output.

Depriving the Soviet economy of its Caucasian oil could have been devastating to it, indeed. In 1940, the Soviet Union was the second largest oil producer, behind only the United States. This gives the impression that the USSR was awash in Caucasian oil, but such was far from the case. The Soviets were also the world's second largest oil consumer, again behind the United States. At the same time as Stalin was exporting 700,000 barrels of oil monthly to Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union was actually a net importer of oil. Unlike the coal-based industrial nations of Western Europe, the Soviet economy was primarily oil-based.

Soviet agriculture particularly was heavily dependent on mechanized equipment. In 1940, the USSR imported over one million barrels of oil from the United States alone. The massive exports to Germany were for political purposes, not economic ones. General Gamelin's assessment of the situation may not have been far from wrong.

Politically, of course, the attack could only have been a disaster. At the time, though, the Allies regarded Josef Stalin with little more trust than Hitler. Stalin had signed the non-aggression pact with Hitler, cooperated with him in carving up Poland, and invaded Finland entirely on his own. To some in the Allied command, the Allies appeared to face a fight now or fight later decision with regards to the Soviet Union.

At the same time as planning for the Caucasus raids was beginning, the Allies were also exploring ideas to aid the Finns with troops and aircraft in their Winter War against the Soviets. Perhaps the most frightening scenario is not that the Allies could have attacked and failed, but that they could have attacked and succeeded. Even with the complete destruction of the oil fields and refineries, the French campaign was over too soon to have been greatly affected. The conquest of France and the low countries actually netted the Germans over seven million barrels of oil, much of it high grade fuel. It was primarily these captured stocks that fueled the Battle of Britain.

The question becomes one not of the German economy, but of the Soviet. Could the Soviets have successfully resisted a German invasion without their oil reserves? Equally important, given a more anti-Allied Stalin, would Hitler have turned east at all in 1941, or would he have continued and concluded his war against the British?

Had the French campaign gone even marginally better for the Allies, the oil field raids could have become reality. Facing a hostile Soviet Union in a friendlier alliance with Germany, the prospects for the Allies would have been bleak. Only the disastrous outcome of the French cam paign may have saved the Allies from their own impending folly and a fate far worse than merely the fall of France.

Sources

Winston S. Churchill, The Gathering Storm, Houghton-Mifflin, 1948.

Robert Goralski, and Russell W. Freeburg, Oil & War, William Morrow & Co., 1987.

Janusz Piekalkiewicz, The Air War, 1939-1945, Translated from German by Jan van Heurck, Blandford Press,

1985.

Playfair, I.S.O., et al., The Mediterranean and the Middle East, Volume I. Her Majesty's Stationer's

Office, 1954.

Back to Europa Number 19 Table of Contents

Back to Europa List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1991 by GR/D

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com