Introduction

Tanks churning across the sands.

Bombs raining down on hapless Malta.

Grim-faced Aussies in Tobruk waiting

for the next assault. Monty. The Desert

Rats. O'Connor. Rommel. What more

could you want in a game?

Tanks churning across the sands.

Bombs raining down on hapless Malta.

Grim-faced Aussies in Tobruk waiting

for the next assault. Monty. The Desert

Rats. O'Connor. Rommel. What more

could you want in a game?

What more, indeed? Games on the campaign in North Africa are immensely popular for rather obvious reasons. Western Desert is superior to most of the other games covering this same topic. It includes a longer span of time than most; it includes some of the other important areas of the theater of operations such as Malta and the Levant; and it has an order of battle detailed enough for even a Campaign for North Africa grognard (if there be such a beast).

Among Europa games as well, Western Desert has advantages. The most obvious is the low number of counters, which increases ease of play and makes the game a perfect introductory game. Western Desert also forces a player to understand how to properly utilize his diverse forces; both sides get to be on the offensive and defensive (often more than once), and both sides must learn how to reach distant goals with few forces.

If any Europa game is chesslike, in being easy to learn and difficult to master, I would suggest that Western Desert fits the bill. Despite my America no-centric prejudices, Western Desert is my favorite Europa game. And one of the reasons I like it is that it forces players to think in terms of strategy. One must be able to think on one's feet, but one also has to be able to look ahead, to weigh different variables, to have a plan, and maybe alternate plans. To win requires effort.

Victory Conditions

Okay, what is winning? Like most Europa games, Western Desert uses victory points to determine a winner. Essentially, victory points are awarded for control of territory and destruction of enemy units. These criteria produce a much simpler distribution of victory points than some of the other games in the series, and this simplifies the strategic goals of both players.

The Axis player can periodically receive victory points for control of Cyrenaica and/or for control of a city in Egypt. He can also receive one-time awards for the capture of Malta, Cyprus, the Levant, or Palestine (good luck), and may earn victory points for successfully bombing the Suez canal as well. The Allies, on the other hand, only receive territorial victory points for control of Cyrenaica and/or a city in Libya outside of Cyrenaica.

At first glance, it would seem that the Axis player has an advantage in accruing victory points. He gets slightly higher victory points for territorial control than does the Allied player, and has the possibility of receiving the additional one-time awards as well. However, the fact that the Italian units lost on the opening turn count as scrapped units means that the Axis player will inevitably start with a large victory point deficit which he must make up. Since the Axis player would be in a tight situation in any event, this puts even more pressure on him.

The Forces

With what can the Axis player accomplish his goals? With what can the Allied player stop him? Proper utilization of one's forces in Western Desert is a necessary key to success.

Axis Forces

Because of the victory point deficit with which the Axis player starts, and because of the nature of the terrain (discussed below), the Axis player must be on the offensive for a considerable part, if not most, of the game. However, the Axis forces are fragile. In the first place, few Axis units have cadre sides. More importantly, they have - compared to the Allies - few replacements. Thus the Axis will find it difficult to replenish combat losses. This means that even though the Axis player must be on the offensive, he must be conservative about taking losses, unless automatic victory is on the horizon.

The Italians form the backbone of the Axis army. As Italians, they have some severe disadvantages: weak offensive power, poor mobility, and an ineffective air force. They are, however, strong in supporting arms, especially artillery. In this respect the Axis is much better off than the Allies.

Moreover, the replacement system does add a little flexibility to the Italian army: an infantry replacement can be used to replace motorized infantry or artillery, meaning that the Axis player can easily replace some of the best Italian units. And some of the weaker Italian units often possess initially unseen strengths.

For example, two 0-8 light tank units and a 3-4-6 artillery regiment are actually a full AECA stack that can thus defeat or inflict losses on an enemy twice or even three times its size. Small units such as these are often referred to as "ants"; in Western Desert this appellation is particularly correct, since they can carry two or three times their own weight, if used properly.

If the Italians are the backbone of the Axis, then the Germans are its fists. They provide the main striking force of the Afrika Korps, embodied for the most part in two incredibly precious panzer divisions.

Even in defeat, the Axis maintains substantial striking power as long as its panzer divisions are intact or relatively so. They are fast and powerful - the best land units in the game. On the other hand, they also serve to underscore the fragility of the Axis. If these divisions are gone, the Axis has lost the majority of its offensive power, and a good portion of its defensive power.

One probably never sees an Axis player praying over his Malta rolls so much as when he is initially shipping over the components of his panzer divisions. Even the loss or significant delay of one panzer regiment can change the course of a game substantially, since it is a long time until the next armored replacement.

In addition to the armored forces, the Germans possess other important assets. The most important of these is the air force. The Luftwaffe is the most powerful weapon in the Axis arsenal; stronger than the panzer divisions and faster, too. The problem for the Luftwaffe is the multitude of tasks that face it. The Luftwaffe will be stretched too far too fast.

One of the primary headaches for the German player will be trying to manage his too-few (and sometimes capriciously available) air assets. Should the Luftwaffe attack powerful Malta to ensure supplies and men get through? Or should it aid the Afrika Korps directly? Or should it bomb the Suez canal, and thus garner more victory points?

The problem is that is must do most of these things, but it can't do all of them. For instance, if the Axis player is on the offensive, he needs both substantial ground support for his troops and he needs to insure a steady flow of supplies from Europe. In all probability, however, the Luftwaffe can't attempt both effectively. It will make the Axis player gnash his teeth, spit out umlauts, and wish that Malta could be invaded.

And that brings us to the last major component of the Axis forces, and perhaps the trickiest, the Special Forces. Unlike the Allies, the Axis player can mount airborne or even seaborne operations, although at a cost. The prime target for these forces is Malta, although there are numerous alternatives. Are the Special Forces worth their cost? The answer to that question depends partially on your own proclivity for using Special Forces, and on the nature of your opponent as well; these factors aside, the answer is only maybe.

The primary potential target for the Axis Special Forces is Malta. In an early issue of ETO, Bill Stone demonstrated pretty convincingly that chances for a successful invasion of Malta in 1941 are slight indeed, and they only improve minimally in 1942. And a 1942 invasion is so far down the line that much of the damage caused by Malta (which in my opinion is much more potent in this game than historically) has already been done. However, such an invasion might still be worth trying, given the immense rewards of success.

Well, what other targets are there? Cyprus is perhaps the most important alternative, and one that is frequently forgotten by the Allied player. Invading Cyprus is less a risky than Malta, but consequent gains are lower as well.

What would it take to capture Cyprus? To insure success, one would have to capture both of the ports on the island. Thus, at a minimum, one would need 2 regiments of parachutists and the requisite transport (say, two transports and two gliders). This means even if the island is completely undefended, one must spend 10 victory points in order to gain 15. If the Allies send even one very weak unit to Cyprus, the possible cost becomes much higher.

The third utilization of Special Forces would be to interject them on the battlefield, presumably from bases in Crete. Depending on the situation, this might be beneficial, especially in constricted areas such as the Qattara Depression. (Remember as well, that unlike most other Europa games, these units exert a zone of control, thus affecting retreat. They do not, however, exert this control on the turn in which they are dropped.)

An alternate ploy might be to drop a regiment onto an Egyptian city to insure the 10 VPs for control of a city in Egypt. Such a move would cost at most 8 VPs, assuming the regiment was destroyed and a glider transport expended.

So there are numerous uses for Special Forces, and though all may not be practical or desirable, at the very minimum they must keep the Allied player guessing. A regiment in Cyprus for the duration of the game is virtually as good as a regiment destroyed.

The Allies

The Allied forces are initially very small. To accomplish significant goals they must take risks, which can be dangerous since at the beginning the Allies are themselves fragile. Losses taken will not be replaced for a long time. The Allies also have poor supporting arms. Throughout much of the game their air power will be inferior to that of the Germans, and for the length of the game they will have a paucity of artillery. Moreover, the Allied forces possess a limited amount of flexibility, generally due to their multinational nature. Though Allied divisions do not have to be built up from particular brigades, they do have to respect nationalities.

This fact, when coupled with the low replacement rate for many nationalities, limits the formation of effective division-sized units. It is quite likely at some point that in one hex the Allies might have a New Zealand HQ, two New Zealand brigades, two Australian brigades, and one British brigade. Their inability to be formed into a division not only denies them the additional strength point that a division possesses, but also means, because of stacking considerations, that less strength can stack in that hex.

On the other hand, the Allies have considerable strengths as well. First of all, they receive generous supplies. They receive as well significant amounts of armor, especially later in the game. And perhaps most importantly, the Allies can sustain substantial losses because of their superior replacement rate.

This gives an Allied player a certain latitude of action; he can, for instance, make a risky attack, without having to worry about severe consequences for the next eight months. It doesn't give the Allied player leeway to make many outright mistakes, but there is a definite cushion.

The Terrain

It cannot be emphasized enough that understanding the nature of the terrain is crucial to winning at Western Desert. Desert warfare is (too) often likened to war at sea, in that the absence of terrain features presents a sort of "pure" warfare, devoid of considerations such as terrain. Well, of course, this is at best hyperbole, and even the most casual glance at a topographical map of the North African Desert (or the Europa maps) shows that there are varied types of terrain almost everywhere in the desert. Utilizing that terrain effectively is extremely important. For Western Desert there are three major considerations (and a host of minor ones, which we will not delve into).

The major terrain consideration is simply the fact that Africa is a continent. That is, it is huge. Even the tiny corner of Africa on which the opposing armies in this game face each other is large. Too large, in fact, for the relatively small forces.

This situation is what made warfare in the desert unique. In general, a player in Western Desert can only have one secure flank - that flank which rests upon the Mediterranean Ocean. The other flank will always rest in the open. Given the relatively high mobility of most units in the game, especially units with high offensive power, this means that an army can almost always be easily outflanked. This in turn places an enormous pressure on both players to retain the initiative. Why? Because only a player with the initiative, presumably forcing the other player to retreat, can afford not to worry about his flanks. There aren't any good ways to defend against this condition, either.

You can stretch out your units far to the south, in hopes that the opposing player cannot move far enough to outflank you, but this usually means that your defending stacks are individually vulnerable. And you still might be flankable. You can adopt a "turtle" defense, placing your units in a concentric circle so that although a player can flank you, he can't at least gain any tactical advantages from doing so. This is essentially the Italian starting position, and is hardly more desirable. And you can keep a powerful striking force to the rear to remove flanking threats. However, because Europa games do not have any reaction phase, this option possesses less value than otherwise, and it also means that your front line will be consequently weakened by the absence of those strong units.

What does all this mean, then?

It means that warfare in the desert will be very fluid, and it will tend to move back and forth between those few point in which there is an alternative to an open flank. The main such location, of course, is the Qattara Depression, which is Santa's big gift to the Allies. Here the British can occupy a front line of just 3 hexes in three different hex rows and 4 hexes in two more hex rows. It is a perfect - and vital - bottleneck for stopping the Germans.

Tobruk is the next important feature, especially when completely fortified, but the terrain is such that an entire army cannot effectively remain on the defensive here. For the next defensible position one must travel all the way west to Benghazi, where the terrain (hopefully complemented by a couple of forts) does present some serious obstacles to an attacker.

An attacker will find that his lines of advance are often not mutually supportable and that the terrain greatly impedes most lateral movement, lessening the attacker's flexibility. Benghazi's main weakness is that it is not a supply terminal, and so it can be cut off. This means that Benghazi can generally be held for only a limited amount of time, assuming a determined attack.

West of Benghazi? There is no equivalent Qattara Depression, unfortunately for the Axis. Near El Agheila, the terrain and the nearness of the map edge provides a minimally defensible position. So, too, does the rough terrain around Tripoli. Neither one, however, is particularly suitable for the defense, as Rommel himself discovered.

These geographic conditions provide the fluidity to desert warfare. At the beginning of the game, for instance, the Axis must face a precipitate retreat, and the Axis player will look in vain for a suitable defensive position east of Benghazi. Thus the long retreat. Usually, the arrival of the panzers and the ill- fated departure to Greece of much of the Allied army means an equally lengthy retreat back towards Egypt.

A situation that many players of Western Desert will probably find familiar is one in which the two armies are locked in a death grip at the Qattara Depression. Neither is quite strong enough to prevail and neither can afford to retreat - an Allied retreat would then open wide the Nile Delta and an Axis withdrawal would be looking at disaster during the long retreat back to (fill in the blank).

Generally, if you feel you have to retreat it is because you are weaker than your opponent. However, if you begin to retreat, you will find that your weaker and slower units will probably be picked off by the other player (if you haven't already deliberately sacrificed them to allow the rest of the army to get away).

Thus, you might make your situation even worse by retreating. The only time this is not true is when your opponent has severe supply problems and can not attack (a problem faced more often by the Axis, of course). In any case, the ability to manage the ebb and flow of the game is extremely important.

A second important terrain consideration really involves the absence of a terrain feature the absence of communication lines. In most instances, supplies will depend upon a single transportation line, one easily cut. Because so many units possess high mobility and because armies can be easily outflanked much of the time, it is not difficult to cut an opponent's supply line, forcing him either to a) retreat, b) burn supply, or 0 waste time, energy, and possibly supply hunting down the offending units. It is often well worth the sacrifice of a 1-10 or 1-8 to deprive an opponent of general supply for a turn or two. This is very difficult to defend against, as well.

Ports

The third major terrain consideration involves the location of ports. Ports are crucial elements of Western Desert. All supply units and reinforcements must pass through them, and so it is very important to have nearby ports. An Axis player just pushed out of Benghazi, for instance, will have to bring reinforcements and supplies over an incredibly long overland route. Ports, because they can bring supply units in, are also an alternative source of supply. Tobruk is perhaps the best example of this; the Allies frequently use it as a bastion, bringing in supply (translation: corned beef and bullets) for the troops as needed.

The most important ports in the game are Tripoli, Benghazi, Tobruk, and Alexandria. However, even the smaller ports along the North African coastline can be crucial - they can at the very least bring in a supply unit or two REs of reinforcements. Because ports can be so important, it is imperativet to deny them to the enemy. Destroy ports in your rear if you know you will be retreating past them. Bomb important enemy ports.

This is often a better tactic for the Allies, since the air units they have are generally not very useful in offensive or defensive ground support. Valletta is also a port, of course, and can be bombed, but repair points will easily fix the damage. Temporarily destroying a port (or ports) on Cyprus would mean the Axis need only take one city to effectively capture the island; on the other hand, such action would also telegraph Axis intentions.

The Campaigns for North Africa

Western Desert opens with the British Wavell/O'Connor offensive against the Italian positions in Egypt. The Allies in Western Desert will spend much of the game in a superior position, or in anticipation of a superior position. Conservative Allied play is usually rewarded in the end; this happened historically, too, as Montgomery (not the dashing, adventurous sort) proved. An Allied player must keep this in mind at the beginning of the game, because for a while his situation is quite different.

How do I mean this? Well, the Allies must open with an offensive, and it will behoove them to be very aggressive and daring on this offensive, in order to reap maximum benefits. On the other hand, in many respects it is a false offensive. Unlike the historical participants, the Allied player knows that in a relatively short period of time a) his forces will be denuded and b) the Germans will show up in force. This means that the goals of the first Allied offensive should essentially be negative.

That is, they should destroy as many Italians as possible and take as much territory as possible.

On the surface these goals do not sound negative, but they really are. Although destroying Italian units on the first turn will yield you victory points, essentially you want to destroy Italian units at the beginning to avoid them augmenting the Afrika Korps later. By the same token, you do not want to take territory for its own sake so much as to deprive the Axis of a suitable base from which it can counterattack.

Thus, though the Allied offensive must be daring, the Allied player must never lose sight of the fact that the offensive is a limited one (because the Allied player will, barring very poor play, eventually lose the initiative) and its success should be measured by how much it managed to handicap the subsequent Italo-German counteroffensive.

How can the Allies achieve these goals? I will not go into the tactical details of the initial Allied attack (early issues of ETO cover this, for those who are interested), but there are a number of things to keep in mind for the first turn or so. The first tactical goal of the Allies is to cut the Italian 10th Army off from supply, so that it will be halved in defense. The Allies will also want to make certain that the construction unit does not escape.

The Allied player may find it extremely tempting to try and bypass the encircled 10th Army to go on to bigger and better things, but this might well be a mistake. The 10th Army, even if just one or two remaining units, is a huge pest to have in your rear. Even if the Axis player, because of supply and zone of control considerations, can only move a unit one hex, it might easily be able to block your line of supply, forcing you to wait, burn extra supply, or take some other action.

A better, though more risky solution, would be to initiate as many attacks as possible on the surprise and first game turns, even at relatively low odds, with the goal of completely destroying the 10th Army. If successful, such a stratagem, though it might cause some losses, will open the way to Tobruk and beyond. The Italian player will not have had time to either retreat far enough or to mobilize more than a scratch defense.

What can the Italians do?

The goal for the Axis player is to stave off or slow down the British army as much as possible. Additionally, he should certainly try to save as much of the Italian army as possible, since much of what dies just won't get to come back. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, the Axis player should always keep in mind the future counterattack.

The 10th Army can be pretty much written off. Although it is possible for a motorized unit or two to escape, much of it will eventually fall. The 10th Army should strive, then, to slow the British down as much as possible before it disappears. A unit with a possible avenue of escape might in the long run help more through sacrificing itself by sitting on the Allied supply line.

In his retreat, the Axis player must deal - as always - with the lack of adequate defensive positions. Tobruk cannot be held by the Italians, especially since it is unimproved. Benghazi then becomes the key position for the Axis player. It is not only reasonably defensible, but is the perfect location from which to launch the eventual German counterattack the next nearest port is Tripoli, which would mean an incredible delay in getting men and supplies from Europe to a beneficial offensive position.

The Axis player should then put up a more-than-spirited defense of Benghazi. By no means should it be a last-ditch defense, since you will need every unit later, but it is worth the loss of some units to retain Benghazi. And keep in mind that all you have to do is delay the Allied player. Eventually the Brits will be flat-out unable to continue the attack. And the initiative will shift inexorably to the Axis. The main danger to defending Benghazi is the risk of being cut off from supply. To this end supply should be husbanded as much as possible in Benghazi.

The Fifth Army construction engineer, as soon as it becomes available, should be sent to Benghazi, not only to build forts if possible, but so that it can remove damage to the port caused by Allied air strikes. Sending a unit or two down to Agedabia might help in deterring or clearing Allied attempts to cut supply.

[Note: If playing with "War in the Desert" rules, an Axis player can simply open Benghazi as a supply terminal, if he is willing to risk losing some victory points. -RG)

An Italian defense of Benghazi is feasible (as a recent issue of TEM demonstrated) and, for the Axis, desirable. -Consequently, it is to the advantage of the Allied player to deprive the Axis of that port. Doing so would delay any Axis counteroffensive measurably, and would give you more time to improve Tobruk, build airfields, and work on the El Alamein line. There are three main approaches to Benghazi: from the northeast, the east, and the southeast. The safest, but most difficult route is from the north. It is, however, an advance easily channeled by the Axis because of the constricting terrain. The Axis can moreover by this point usually form at least one stack and often two that have significant ATEC capabilities, which together with the terrain can hobble your attack further.

The middle route is harder for the Axis to defend against, but a heavy thrust in the middle leaves covering forces in the north vulnerable to Italian and especially German counterattacks. An approach from the south would cut the Axis supply route, but any such Allied force would also be out of supply.

However, even a small diversion can force a substantial Axis response. In any attack at Benghazi it is important to insure that the Axis can't ship units to the port. This is accomplished through bombing and through increasing as quickly as possible the anti-aircraft strength of Malta. I have found that Benghazi is a difficult nut to crack if the Italians have saved some supply and haven't wasted their army. It is not by any means impossible to take, however.

Even assuming that the Allied player takes Benghazi, at some point he will notice that the initiative has started to slip away from him. It is extremely important for the Allied player to realize when to quit pressing the offensive (or the stand-off, as the case may be) in Libya, because it is difficult to retreat successfully, and the Allied player will need to preserve every possible Allied unit (because the next few months will be by far his most desperate period).

The Allied player is thus faced with the typical Western Desert quandary: if he does not retreat, he will probably be cut off and might lose most or all of his army; on the other hand if he starts a retreat he will certainly lose at least some of his army, and might be unable to stop retreating. It is a real dilemma.

Probably the key sign to note is the ability of the Germans to form a complete panzer division. However, since the Axis player turn is after the Allied turn, the Allied player cannot be certain when this will occur. If the Malta status table is unfavorable to the Allies, then definitely a retreat of some sort should begin; otherwise the Allied player might be able to risk waiting. If Benghazi has been captured, then retreat becomes easier because of sea transport. If the Allies are still outside Benghazi, the retreat is dicier.

One situation that both sides might easily face at some point during a game is where a player has few (or even no) units in his army, and the enemy is barreling down the coastal highway towards his objectives. The natural reaction is to hit the panic button, but things might not be that desperate. I witnessed a game a couple of years ago where the Axis, holding Benghazi, counterattacked and surrounded virtually the entire Allied army north of the port.

Having no forces at hand, the Allied player panicked, and so to save Egypt he scrapped large numbers of units in the replacement pool and brought in all possible garrisons in order to form a line along the Qattara Depression. What happened? Well, it took the Axis a long time to advance all the way up and around the coast, especially the poor tired Italian infantry, and in the meantime the Axis started having some pretty serious problems getting enough supply through. Thus by the time the Axis was in a position to attack, and had the ability to attack, the Allies had already received numerous replacements and reinforcements, including the remnants from Greece.

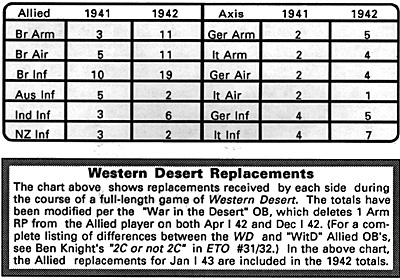

The replacement points

generated from the scrapped REs were

handy but hardly needed; the lost

victory points hurt the Allied player

more than the reinforcements helped.

The replacement points

generated from the scrapped REs were

handy but hardly needed; the lost

victory points hurt the Allied player

more than the reinforcements helped.

The game Torch presents a similar situation initially, with the German player looking at every unit in the world heading towards Tunisia. The moral? The Clausewitzian concept of friction applies even in cardboard wars. Africa is big, as mentioned before, and things may not be that bad.

So - the Allies are probably retreating. They must retreat a long way. Tobruk is not a tenable position for the army as a whole to defend, but it is important that Tobruk be held. While it is probably not as crucial in Western Desert as it appeared to be in the actual campaign, an Allied-held Tobruk behind the main Axis advance provides numerous important advantages:

- 1) Most obviously, it denies

the Axis use of that port.

2) Tobruk also sits astride the coastal road. For the Axis to supply the Afrika Korps, then, it must garrison the three hexes surrounding Tobruk with units. Moreover, these stacks must be substantial enough that an Allied sortie from Tobruk can't easily destroy one or more. This, of course, decreases greatly the Axis strength at the major front line, probably along or near the Qattara Depression.

3) Lastly, Tobruk can serve as a base for a counterattack. And any successful counterattack might throw all or most Axis forces out of general supply.

Tobruk is very defensible, but not immune to Axis attack. Ben Knight's article in ETO #25, "How to Break Tobruk," illustrates how the Axis might successfully prosecute the capture of this fortress.

If an Axis attack succeeds, or if the Allied player abandons Tobruk because he feels too weak to defend both it and the El Alamein line, then any Axis thrust eastward will have more impetus.

The line at El Alamein then becomes the final line for the Allies. There is no point to think about retreating from El Alamein; it all goes downhill from there. As Stalin might have said had he been British: "There is no land beyond Qattara." Western Desert reaches a fever pitch of excitement whenever the two players butt heads at the Qattara Depression, because although things often turn into a less-mobile slugging match, the outcome is usually crucial. For the Axis player especially, it is essential to crack this line, because the Allies will never be weaker. Moreover, the risks of failure will be great, and unlike Rommel, the Axis player will probably not get a chance for a second great offensive.

At this point the analysis should probably be stopped. Games of Western Desert span a period of time long enough that after a certain point no two games retain much similarity. It becomes too difficult to predict the ebb and flow of hypothetical games past this point, as too much depends upon the individual players and their actions. In games I have played or witnessed, it seems that if the two players fight it out along the El Alamein line, and the Axis does not break through, what often follows is a long stalemate along that line, followed by a long, slow Axis retreat (eventually to Tripoli). However, it is impossible to predict such occurrences.

I hope, therefore, that this article has illuminated some of the more important strategic considerations to keep in mind when playing Western Desert. I didn't discuss certain areas, such as an invasion of the Levant, or Axis involvement in that area, because of the relative infrequency of such occurrences. Instead, I concentrated on what I felt were the more important areas. Western Desert makes me appreciate the ability of Rommel - and Montgomery, too - to understand the nature of the war being fought, and it is my desire that this article has helped readers to appreciate the nature of Western Desert.

See you next time in more northerly climes.

Back to Europa Number 15 Table of Contents

Back to Europa List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1990 by GR/D

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com