Second Front playtesting is progressing well. The 1944 campaign scenario, which lasts from spring 1944 to the end of the war, has been played through to completion about 15 times so far, with many more games in progress. Fourteen games have ended in the collapse of Germany and one game has seen an Allied defeat.

The usual course of the game is that the Allies grind away in Italy and land somewhere along the English Channel from France to the Netherlands in May or June. The Germans contest the landing, and both sides pound away during the summer: the Allies relentlessly expand their beachhead while the Germans plug the gaps and counterattack wherever possible.

By autumn the Germans run out of troops and fall back to Westwall. In Italy, the Allies usually can break the Germans in 1944 - especially if no troops are siphoned off to France - and reach the Alps, where they face a long mountain campaign. On the Westwall, the Germans hold on until their final reserves run out, whereupon the Allies sweep across Germany. This usually occurs in early 1945: the quickest Allied victory happened in late 1944, while the longest went into the summer of 1945.

The sole German victory occurred in autumn 1944. The Italian front stalemated early and permanently. In France, the Allied invasion was sealed off and never managed to break out. Massive panzer attacks slowly dented the perimeter, and the Allies gave up when they started losing their invasion beaches. It's unclear whether the Allied players were inexperienced or were very unlucky.

Playtest

In Issue #12, I covered the start of the Virginia playtest group's first game. I left them at the end of July, with Allied beachheads in Normandy and Brittany and with the Germans in collapse in Italy. Continuing their story...

Aug I 44: The Germans fall back to the Seine River, forming the line Le Havre-Paris-Orleans. Following up, the Allies surround an entire panzer army at Orleans. In Italy, the Germans are caught between the main front in the central Apennines and the major landing around Genoa. They pull back what they can, but the Allies surround or smash 14 divisions near Florence. The Genoa beachhead breaks out, taking Milan and crossing into France toward Lyon.

Aug II 44: German counterattacks extricate most of the Orleans pocket, but two infantry corps are cut off at Le Havre by new Allied attacks. Emergency forces in Wehrkreis XVIII (the part of Austria next to Italy) activate, but Allied air power prevents them from reaching the front. The Allies reduce the Florence pocket.

Sep I 44: The Germans retreat in France, as the Allies liberate Paris and pocket many withdrawing forces. In southern France, the Allies invest Lyon and will link up with the main forces shortly. The Germans form a line west of Venice, which the Allies pierce in the north and south.

Sep II 44: German counterattacks in France cause American losses but fail to relieve surrounded panzer forces. The Germans fall back to Belgium in the north and close up to the Westwall elsewhere. The Allies mop up the pockets, while an American rush pierces the Westwall and the Rhine at Freiburg. In Italy, the Allies grind toward Venice.

Oct I 44: In Germany, counterattacks force back the Westwall rupture, but the Americans hold onto the Westwall hex itself. Elsewhere in the west, lines form up in central Belgium and along the Westwall. In the MTO, Allied forces push into the Alps, heading toward Austria.

Oct II 44: The weather turns bad. A massive attack pushes the Americans out of the Westwall and back across the Rhine. In the north, Allied airborne forces land in the Netherlands in an attempt to open a road into Germany. The British drop near the coast fails to link up and is subsequently destroyed. The American drop west of the Ruhr succeeds, and U.S. motorized forces enter the western Ruhr in exploitation. The Westwall is penetrated near Luxembourg, and Germany once again faces a crisis on its borders. The Italian front continues to slow as the Germans form a line in the Alps.

Nov I 44: The Germans scrape up every panzer formation they can rush to the Ruhr, counterattack, and cut off the Allied spearhead, trapping five divisions. The U.S. Army immediately breaks through to the pocket, but withdraws its forces from the Ruhr to consolidate its lines. Allied forces reach the German border in the Alps.

Nov II 44: An Allied carpet bombing attack blasts the Allies a path back into the western Ruhr, but otherwise progress is slow on all fronts.

Dec 44/Jan 45: The Allied push through the Netherlands and into northern Germany, as the bulk of the German forces protect the Ruhr. South of the Ruhr, the Allies surround portions of the Westwall and push toward Stuttgart. In the Alps, the Allies enter Austria and take Innsbruck. Only bad weather prevents Allied armor there from breaking out into Bavaria.

Feb 45: The German Army is exhausted and gives way everywhere, trying to form a line on the Elbe - the only possible defensive line before Berlin. Pockets hold out in Stuttgart, Mannheim, and part of the Ruhr, while the Allied advance reaches the outskirts of Hamburg, Nuremberg, and Munich. American troops take Magdeburg, only 80 miles from Berlin.

Mar I 45: The Allies gain three bridgeheads across the Elbe in northern and central Germany one is only about 60 miles from Berlin. The rest of Bavaria falls, with the Allies reaching the 1938 Czech border and having two spearheads within 100 miles of Vienna. Facing a hopeless situation, the Germans unconditionally surrender.

Scenarios

I get many requests for scenarios for existing Europa games, from everywhere, including the editor of this magazine. I'd love to have more scenarios. Trouble is, it takes tons of time to do a large scenario right - almost as much as it takes to do a game. Sure, the units are already rated and the rules exist, but that's only the beginning. You almost have to do the research all over again, to pin down where the units are on the scenario start date, what condition they're in, and (if the scenario covers only part of the maps) when off-map forces arrive as reinforcements on-map.

For example, I've got almost everything I need to do a 1941-42 Crimea scenario for Scorched Earth, except for a good Soviet order of battle of their forces there. After a tough fight, the Soviets ended up getting their clocks cleaned by Manstein, and their histories are accordingly spotty about this campaign. German intelligence estimates aren't much help here, either. With time and patient work, I can eventually put together the Soviet OB for the scenario. I have the patience, but not the time. Currently, Second Front, Balkan Front, and For Whom the Bell Tolls are my Europa priorities.

So, how about a really small scenario? It's short, simple, historical, and, in true WW2 tradition, completely unbalanced. (Well, we can't have everything!)

Here's the background: In the years preceding World War II, the bomber gained prominence as a warwinning weapon in the military theory of various countries, particularly in Britain and the United States. Why, you could build a fleet of bombers, fly over the enemy, and then obliterate him with bombs, without raising mass armies to fight deadly battles of attrition. And, the enemy couldn't defend against the bomber - AA was inadequate, and fighters couldn't catch it. (In the 1930s, bomber technology surpassed that of fighters. Multi- engined bombers were faster than the fighters of the day, which led many nations to believe that bombers would always be able to evade fighters.

Of course, the technical edge was only temporary, and fighters regained their advantage as soon as highhorsepower engines became available.) Many countries set their basic air strategy believing in the superiority of the bomber, and paid the price when theory met reality.

For the R.A.F., reality set in on 18 December 1939. From the outbreak of the war, Britain had waited for the dreaded "knockout blow" from the Luftwaffe, expecting an immense swarm of German bombers to ignore the small R.A.F. and smash British civilization in a hail of bombs. Of course, nothing like this happened. Instead, German warplanes were rarely seen over English skies, and the British started on the road to launch their own knockout blow.

There was only one problem - Bomber Command (BC) wasn't big enough. BC knew what it wanted to do, and had ambitious plans to build enough bombers (they thought) to do the job, but in the meantime they had to get by with limited resources. They didn't want to antagonize Germany into launching a retaliatory blow as long as the Luftwaffe remained superior. Hence, BC was limited to dropping propaganda leaflets and bombing purely military targets, especially naval ones.

On 18 December 1939, the R.A.F. launched a large (for 1939 R.A.F. standards) daylight raid of Wellington 1C bombers against Germany. Intercepted by single and twin-engined fighters, bomber theory met fighter reality. Before I tell you the results of the engagement, here's the scenario:

This is a two-player scenario, involving air units only. Given the scale of forces involved, air units are shown at half-group size (half Europa standard size). No map is needed, since all the scenario consists of just an air combat phase between the two sides. Use the Scorched Earth or Torch air rules, but don't allow either side to abandon their missions. This is a day air combat.

British Forces:

British Forces:

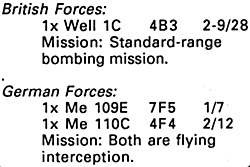

1x Well 1C 4B3 2-9/28

Mission: Standard-range

bombing mission.

German Forces:

1x Me 109E 7F5 1/7

1x Me 110C 4F4 2/12

Mission: Both are flying

interception.

(Editor's Note: The above air

units reflect the most recent air unit

ratings and thus require some new

counters, as provided below.)

(Editor's Note: The above air

units reflect the most recent air unit

ratings and thus require some new

counters, as provided below.)

Victory Conditions

- British Major: Well 1C survives

with no ill effects to bomb target.

British Minor: Well 1C turned back

German Major: Well 1C shot down

German Minor: Well 1C aborted.

The historical outcome was a German major victory. The Luftwaffe severely mauled the Wellingtons, shooting down over 12 of the 22 aircraft, and damaging many of the others (two of which crashed upon landing). While this engagement may not rank up there with late-war 1,000 plane raids, it wasn't insignificant.

The R.A.F. woke to the reality of the situation and abandoned flying daylight bombing raids over Germany three years would pass until large scale Allied bomber formations again flew by day over Germany. Bomber Command had to switch to night bombing, in essence abandoning its reason for existence. With the immense problems of trying to fly to, find, and then accurately bomb targets at night, nothing resembling a knockout blow was possible, and by mid war, British strategic bombing had degenerated into little more than nighttime terror bombing raids on civilians.

Asking and Answering

I think there should be some sort of limits on parachute drops - perhaps no drop further than 10 hexes from the front line, except for commandos. I'm tired of the Nazi sky gangsters dropping all over Russia when the Germans never launched any large drops there. How about it?

So sorry, no. I've heard all sorts of schemes on why para drops should be limited and how to do it. None are convincing, and the proposed rules end up prohibiting what was possible, what was planned but not executed, or what actually occurred.

For example, your limit (supposing we can define "front lines") makes some historical drops illegal, such as the German drop on Crete. If you extend the range to cover Crete, then what about Cyprus? Cyprus was a legitimate objective for a drop, and the British stuffed the island with troops in 1941 after the lesson of Crete, to guard against this. The cities of Cyprus lie about 25 hexes from the nearest Axis forces and airbases (on Rhodes). Increasing the limit to allow Cyprus means there isn't much of a limit at all. And, give me a limit of 25 and I'll find an island 30 hexes away that likewise should be a target.

So, the next "fix" I often hear is to limit drops to so many hexes on the mainland and allow unlimited range for islands. This gets silly quickly: you could liberate Copenhagen (on Sjaelland Island) by a drop from Britain, but en route you couldn't release the paras on the Jutland Peninsula! Also, the rule would preclude a serious proposal for D-Day: rather than dropping near the coast, airborne forces would drop on Paris, liberating the city and clogging German communications to Normandy. Allied forces would hold out in Paris for the time it'd take Montgomery to break out from the beaches and link up with them. (While we know from history that Monty would need a couple of months even to break out of a paper bag, this wasn't as evident then.) Finally, what about the island of Britain? Everywhere is wide open because it's an island? Geography simply isn't the answer.

About this point, the paralimiters usually drop the pure range limit argument and switch to "linking up". Unlimited-range drops are allowed for islands, but on the mainland you can drop in a hex only if your ground forces can conceivably link up with it, through overland movement by the end of your drop turn. I'm not sure how you'd figure this ignoring the presence of enemy forces when seeing where you can move overland doesn't seem right, but trying to calculate your best moves, attacks, and exploitation in advance to see if it's legal to drop in a hex is hopeless complicated.

In any event, the rule would probably make the Paris option impossible. Also, what about all those island-like features on the mainland? The Crimea Peninsula is about as close to an island as you can get without actually being one: the only land access is one hex at the neck, a nearby causeway, and the Kerch Straits. Seal off these points when you drop, and you essentially have an island campaign. As some Soviet players who neglect the Crimea have found out, the Nazi sky gangsters can land, block off the place, and hold it until Army Group South arrives. Also, what about a place like Gibraltar? Do you really want to make it airborne-immune as long as Spain remains neutral (hence precluding an overland linkup)?

Rather than a contorted rule that limits paradrops, let's model what went on in WW2: airborne troops can drop anywhere their transports can reach. Garrison important rear-area points to guard against the paras, and hit hard those paradrops that are out on a limb during your turn. Do this, and the enemy will either run out of airborne troops (due to their low replacement rate) or will avoid risky drops unless the potential payoff is high enough.

Get rid of resource points! When you play the games, you are a General in charge of armies. Having to shepherd the resources to build forts and airfields is something handled by your staff, and not directly by you.

Resource points impose a top limit to the number of forts and permanent airfields you can build. Without this limit, players would marshal their engineers and build forts and airfields until every hex they control was stuffed. This is incorrect - doing this would exceed the actual capabilities of any nation, and it would have a bad impact on the play of the game. We can usually ignore this in short games, as players rarely can take maximum advantage of unrestricted construction over just a few turns. In longer games, limits are necessary.

Given the need for a limit, resource points fulfill this need. A less flexible approach would be to set a maximum limit on the number of forts and permanent airfields a player can start to build each turn. This does get rid of resource points, but at the cost of being able to build things as the situation demands.

There is an acceptable way to speed up the resource point rule: don't put the suckers on the map. Instead, keep them in a pool off map and expend them as needed. But, be warned: you'll need a reasonable group of players to play this way. If you've got a crybaby in your group, then all you'll hear is how "no way you'd be able to spend a resource point in THAT hex if we were using the REAL rules."

If you feel like experimenting, the next time you play Fire in the East/Scorched Earth, drop the resource point costs for operations in the Arctic. I suspect the game won't play significantly different, but I've never had the luxury of testing this minor point. If you try it out, let me know what effect it has.

Why do motorcycle units have heavy equipment? You should be able to fit them on an air transport.

Yeah, and what happens when they run out of gas? You can't fit their supply trucks in a Ju 52 or C-47! Seriously, there are very few completely "pure" unit types at Europa unit sizes. An infantry division has much more than infantry in it, a tank brigade often has a battalion of motorized infantry in, and so on. Motorcycle units had very different compositions, depending upon nationality, but anything larger than a battalion almost always has a mix of heavy equipment.

While the bulk of the troops will be equipped with motorcycles, often the unit headquarters will be truck-borne, as may be various of the unit's heavy weapons. Also, a motorcycle unit may have some armored cars or light tanks in it, too. Finally, the unit's support services will be in trucks, such as its signals section and supply column. All this adds up to enough heavy equipment to keep the motorcycle formations off the air transports.

Why don't U.S. construction engineers have heavy equipment? Their TO&E gives them bulldozers and dump trucks.

- (Editor's Note: Although these

units were listed as possessing heavy

equipment in War in the Desert, this

has been revised in Second Front.)

While the U.S. had the resources to lavish heavy construction equipment in the individual construction units, this doesn't mean that only American engineers had use of such machinery. Other nations would often pool their construction equipment at a higher level and parcel it out as needed, rather than permanently give it to individual units whether or not they needed it at any particular time. It keeps the game simple to treat the U.S. the same as everyone else here: the construction engineers represent the troops with the skills and abilities for construction, and the heavy equipment needed for the job is assumed to be on hand if and when needed.

OK, I'll buy the U.S. being treated like everyone else here. Shouldn't all construction engineers, however, have HE, since they have heavy equipment on call?

The skill and abilities of the engineers themselves are the important consideration, not their particular equipment. I assume you are concerned about flying them around. If so, then the crucial question is: Should you be able to fly in the troops with the knowledge of how to build forts and airfields, even if some of their equipment can't come? I say yes.

The troops will be able to accomplish their tasks through manual labor and local resources even if their equipment doesn't show up - while if the equipment is on hand but not the skilled troops, nothing of consequence is going to get built.

What about having light and heavy antitank units, like light and heavy AA?

Nah. It'd complicate the game without adding much of value. Light and heavy AA is a useful distinction, since heavy AA has ATEC. I suppose light and heavy AT could have half and full ATEC, respectively, but this isn't a useful distinction. AT units had one job - shoot tanks - and all nations continually upgraded their AT units to the demands of the job. For example, a German AT battalion that started the war with 37mm AT guns didn't stay that way throughout the war. The 37mm gun was a powerful gun at the start of the war, capable of handling most types of tanks it encountered. As the tanks improved during the war, the gun became less and less able to handle them, until the Germans re- equipped the battalions with more powerful guns, such as towed 50mm, 75mm, and 88mm guns or even self- propelled guns such as Marder III, Sturmgeschutz IIIG, Hetzer, and so on.

While it's true that a nation's AT units would occasionally lag in comparison to an enemy's tanks, this rarely becomes significant at Europa scale. The most famous case is the German 37mm "door knockers" being ineffective against Soviet T-34s and KVs in 1941. This is handled in Fire in the East/Scorched Earth by making German AT units 1/2 ATEC rather than full in 1941.

And, I'm not even sure that this is the correct way to do things - I'm inclined to make them full ATEC anyway. While the 37s had trouble with T-34s and KVs, most tanks the Soviets fielded in 1941 were other types with much lighter armor, which the 37s could handle. The Soviets had limited quantities of T-34s and KVs and parceled them out carefully.

In general, no more than a third of the tanks in a unit would be T-34s or KVs, and the rest would be lighter fare. (In 1942 higher production allowed the Soviets to increase the proportion of T- 34s in their units, but the Germans were also issuing better antitank guns by then.) Before you start sending in the war stories of the Germans facing hordes of T-34s in the 1941 Soviet winter counteroffensive, let me remind you that Allied soldiers were equally convinced that every German tank they saw on the Western Front in 1944 was a Panther or a Tiger. In both cases, 'twern't so.

On top of most Soviet tanks not being T-34s/KVs in 1941 is the fact that almost all Soviet tank crews were inexperienced. While the Germans could see that the 37s had little chance of penetrating T-34s except at short ranges, this wasn't as obvious to the Soviet tankers. Being hit by a 37mm round was noticeable inside a T- 34, even if the round didn't penetrate. It served notice that you were in range of the enemy, who might be able to punch through with their next shot - especially if some 88mm AA guns were also in the neighborhood. While there were many heroic Soviet tankers who charged into battle regardless of the odds, there were many more who'd break off the attack once they came under fire.

With the above two considerations, I'm inclined to think that full ATEC is more appropriate than 1/2 ATEC for German antitank units in Fire in the East/Scorched Earth.

If you fly extended range, you get double range but your air combat strengths are reduced. If you fly transfer, you get triple range and your air strengths are unmodified. Shouldn't strengths be reduced for transfers, too?

No. The range of an air unit is based on how far it can fly under normal conditions, using a standard combat and fuel load.

For example, a bomber with its standard crew, armament, fuel, and bomb load might be able to fly 800 miles from point to point under these conditions. Of course, it wouldn't ever fly a bombing mission to a target 800 miles away, as it would run out of fuel over its target and crash. Since aircrew were somewhat leery of crashing, they usually turned back with enough fuel to return to their base. Also, it couldn't just fly out half its range, drop its bombs, and then fly home. Aircrew were suspicious about arriving back at base with no fuel at all left, as they thought this might lead to crashing.

More importantly, this strategy leaves no fuel for anything else, such as forming up, loitering over target, flying deceptive courses, adverse flying conditions, and so on. Europa takes all these factors into account, making an air unit's range rating somewhat less than one third its normal one-way range.

In order to extend flying range, an air unit has to carry more fuel. The weight of the extra fuel has to be compensated for by reducing the weight of other items being carried. Typically, this means carrying fewer bombs, less armament, and/or less ammunition for the armament. Hence the bombing and air combat reduction for an extended range mission.

The same isn't true for a transfer mission. You don't have to worry about returning to base, since once you're at your "target" you're already home. Also, there's fewer fuel- wasting maneuvers. There's no need to loiter anywhere, for example. Also, there's less need for zig-zag flying or other deceptive measures, as you can usually pick a good time to transfer, such as at night, when the enemy's less likely to be around. So, you can transfer at triple range - which, remember, is still slightly less than your normal one-way range - with a normal load. Hence, no combat reduction is needed.

But, if your transfer mission is intercepted, you can abandon the mission and return to any base within triple range of the target hex, even to a hex six times your range from the base you took off from! How can this be?

This is so insignificant that it's not worth having any special rules to cover it. In order to abuse the rule, you'll need a situation along these lines: You have two pockets of territory, and you want to transfer an air unit from one to the other.

Unfortunately, there's no safe route from one to the other where you can do a multihop transfer to get there. Instead, there's this airfield you own that's triple range between both pockets, but the enemy can intercept you there. So, you fly a transfer mission to that airfield. If the enemy intercepts you, you abandon your mission and fly to the other pocket to land. Now, when was the last time something like this occurred or even could have occurred in one of your games? And, in the unlikely event it did happen, did it really matter?

If we need to add more rules to remember, let's add them on something significant. If you really need a special rule here, then the transferring air unit must land at its target hex, even if turned back by air patrol, upon abandoning its mission, or taking an "R or "A" result in air combat.

On second thought, the likelihood of rules abuse in a situation like the above seems even more remote. Why go through all that bother when you can transfer at night? Now, your intermediate airfield is only blocked if it's in the patrol zone of a night fighter. Sure, you do have a minimal chance of crash landing a day air unit if you transfer at night, but again this is something I can't get worked up about much.

Even without a dirty trick such as above, you can usually transfer anywhere safely by leapfrogging about, avoiding enemy patrol zones. Why not let a transferring air unit go to any friendly airbase on the map regardless of range and forget about patrol attacks? It'd make things simpler and faster-no counting triple range routes or calculating patrol zones.

If you want to play this as a "quick" house rule, go ahead. Unfortunately, it has some problems in some games. For example, it allows the British to transfer between Malta and Egypt in Western Desert. With the current rules and as was the case historically, the British had major problems getting aircraft, fighters especially, from Egypt to Malta since the Axis controlled the intermediate airfields.

(And here's a free "sick trick" for that game: Transfer a Well 1C from Egypt to Benghazi, have the Germans intercept it, and thus "return" it to Malta. Let me know if you ever get away with this, and if you win the game because of it.)

Beyond this example, there will be numerous similar situations in Grand Europa: The Italians will have problems getting to Rhodes from Italy until they control Crete. The British will have trouble getting from Britain to Gibraltar, Malta, or almost everywhere once the Germans sweep France. So, use this house rule only for situations where you don't have remote enclaves.

In Scorched Earth, it seems that partisans have no effect on enemy units moving through the area they occupy. Wouldn't they try to harass the unit moving through, slowing it down? Maybe you could have a partisan counter count the same as a harassment hit for enemy movement.

Good try, but you overestimate the effectiveness of partisans. Even a small combat unit, such as a battalion, is too tough for the partisans under most conditions. Instead of trying to harass the unit, the partisans in its vicinity will do their best to hide from it. Unless the partisans have overwhelming force or complete surprise, an encounter between partisans and regular combat units is going to be bad news for the partisans, not the regulars. The standard procedure for partisan warfare is to avoid the regular troops and hit the enemy where the regulars aren't around, and the rules cover these considerations.

Back to Europa Number 14 Table of Contents

Back to Europa List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1990 by GR/D

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com