In January and February of 1995, Peru and Ecuador fought their third border war, this time over the Cenepa River Valley salient. The full story of this conflict may never be known, but enough details have emerged to make a fairly detailed analysis. Ecuador suffered humiliating efeats in 1941 and 1981. In the fourteen years since 1981, the Ecuadorian military has striven to correct the deficiencies that had led to the route it suffered in 1981. The most evident improvement was in the weapons, and equipment used by the Ecuadorian side. However, on top of the technological changes, the most important differences were in the tactics, logistics and communications enjoyed by Ecuadorian forces in comparison to those of 1981.

In January and February of 1995, Peru and Ecuador fought their third border war, this time over the Cenepa River Valley salient. The full story of this conflict may never be known, but enough details have emerged to make a fairly detailed analysis. Ecuador suffered humiliating efeats in 1941 and 1981. In the fourteen years since 1981, the Ecuadorian military has striven to correct the deficiencies that had led to the route it suffered in 1981. The most evident improvement was in the weapons, and equipment used by the Ecuadorian side. However, on top of the technological changes, the most important differences were in the tactics, logistics and communications enjoyed by Ecuadorian forces in comparison to those of 1981.

It is difficult to believe that there was not at least some planning on the part of the Ecuadorians for the last war. They may not have been intentionally picking a fight, but they seem to have carefully chosen the territory they would lay claim to so that it gave them maximum advantage in case Peru reacted violently. The maps show clearly that the terrain heavily favoured the Ecuadorian side.

The Cenepa salient is surrounded by high ground on three sides by recognized Ecuadorian territory. The Peruvians occupied the low ground on the southern end of the valley. On the right bank of the Cenepa River, at the center of the mouth of the salient, Peru occupied Border Post 1 (PV 1) at 845 meters above sea level. At the south-western corner of the salient, on the left bank of the Cenepa River, Peru occupied PV 2 at 1,218 meters above sea level. PV 2 was for all intents and purposes outside of the area of operations. To the west, facing PV 2 from the Ecuadorian side was border post Condor Mirador at 1,780 meters above sea level, a vantage of 562 meters. Further up the west end of the salient was observation post Zumbi at 2,571 meters above sea level.

This post was somewhat to the north of PV l and held a height advantage of 1,726 meters! At the northern end of the salient, the Ecuadorians had the Numbat Kayme landing strip for helicopters and light aircraft, and not too far north of this landing strip there was an aerodrome for heavier aircraft. On the south-eastern corner of the salient, Ecuador had border post Coangos at 1,617 meters. Coangos was pretty much in line with PV 1 and enjoyed a height advantage of 772 meters over PV 1.

This was important because the Ecuadorians posted artillery and heavy mortars at Condor Mirador, Zumbi and Coangos. This included Soviet designed BM-21 122mm multiple rocket launchers that Ecuador had reportedly obtained from Nicaragua after the fall of the Sandinista government. On the western side of the valley, Zumbi and Condor Mirador could be reached by road. On the east, a road reached border post Banderas, which was a short distance from the Coangos border post, by boat, along the Coangos river, or by helicopter. The Ecuadorians could reach their main outposts by land, air or water. The Peruvians could either use the river to move supplies or fly things in by helicopter. The only land connection were narrow foot paths. The height advantage of the three above mentioned Ecuadorian border posts mean that their artillery could dominate any location within the area of operations, and the roads and better logistical arrangements meant that Ecuador could pour more resources, men, supplies and equipment into the area than could Peru. This would play a decisive role in the conflict. There were essentially three locations being contended for, Tiwinza itself, at 1,061 meters above sea level, about equal distance between the Ecuadorian border posts of Coangos and Banderas. Further south were Base Sur and Cueva de los Tayos. A roughly straight line could be drawn between Coangos and PV 1, with Base Sur being about a third of the way on that straight line between Coangos and PV 1 and Cueva de los Tayos being about two thirds of the way along that straight line between Coangos and PV 1. A major trail ran between Coangos and Tiwinza. Somewhere between Coangos and Tiwinza, the trail split with one branch going to Base Sur. The point where the trail split would become a major land mark in the battle to come, known by both sides as the "Y.',

The War

The Peruvians claim that they began detecting Ecuadorian encroachment on the Cenepa river valley in the early 90's. There were a number of incidents with patrols from both sides running in to each other. The outcomes were friendly and cordial with no bloodshed. However, starting in the latter half of 1994, Peruvian patrols began running into Ecuadorian patrols building and occupying bases in the region. These usually consisted of a few huts and a helipad. The Peruvians began to send more patrols from the 25th Jungle Infantry Battalion (25 BIS) to confirm their information.

On January 9th, 1995, the Peruvian patrol "Rommel" (Peruvian patrols were code named after the name of the officer in charge) of four men was surrounded by twenty Ecuadorians and confronted. "Rommel" told them he and his men were lost and was escorted to Cueva de los Tayos and turned over to another Peruvian patrol under "Tono". On the 11th the Peruvian patrol "Tormenta," was ambushed at the "Y." The Ecuadorians challenged the point man, and when the officer responded they were Peruvians, there was a momentary lapse as the Ecuadorians cocked their rifles and machine-guns. This was just enough time to allow the Peruvian patrol of 20 men to dive off the trail and take cover.

As a result there were no Peruvian casualties from the incoming machine-gun and rifle grenade fire. The Peruvians answered with rifle fire, an RPG-7 rocket launcher and "Strim" rifle grenades. However, the Ecuadorians had them trapped in a hole. For three hours the fight continued with no victor. One Ecuadorian soldier that had climbed up a tree was shot and fell out dramatically, Hollywood style. After three hours of battle, another Peruvian patrol "Lince," arrived and laid down supporting fire which forced the Ecuadorians to withdraw. Two Ecuadorians were killed and two Peruvians wounded. Fourteen Peruvians went missing, although they made their way back the next day.

On the evening of the 11th, the two commanders of the opposing units spoke to each other on the radio. The Ecuadorian colonel Aguirre told the Peruvian Lt. Col Lazarte not to send patrols into the Tiwinza sector. The Peruvian commander told the Ecuadorian that if they didn't get out of Peruvian territory, they would be forced out by the bullet. Immediately afterward, the Peruvians began to prepare to eject the Ecuadorians from the valley. The very next day, the Peruvians ordered several patrols out to build helipads in strategic locations near the Ecuadorian positions.

Between January 12 and January 18, the patrols "Roosevelt" and "Tormenta" built their pads. "Tormenta" built theirs to the south of Tiwinza on hill 1274, on the west side, to keep their activity secret from the Ecuadorians at Coangos. From this helipad, named "Tormenta" the Peruvians could overlook the "Y" and observe activity at Coangos. "Roosevelt" built their helipad to the north of Tiwinza, at the intersection of the Fashin stream and the Cenepa river. The Ecuadorians began sending out a Remotely Piloted Vehicle at night to detect the nature of the Peruvian activity. Several Peruvian soldiers could hear the propeller of this small plane as it made it's nightly flights. It is probably in this manner that the Ecuadorians discovered the helipads of "Roosevelt" and "Tormenta." On January 19th, an Ecuadorian patrol conducted a probing attack of the "Tormenta" helipad. After a short time, they withdrew. An MI-8T began to fly in supplies and reinforcements to helipad "Tormenta." When the helicopter was overhead, the Peruvians on the ground would signal the craft and uncover the landing pad.

As soon as the helicopter took off again, the Peruvians would recover it with vegetation. The Ecuadorians knew the vicinity of the helipad, but not the exact location. The Ecuadorians, having detected the two helipads decided to take the initiative and push the Peruvians back. They were not going to wait to be attacked from the front and the rear by heliborne forces. On January 22, another Ecuadorian patrol, trying to locate where the Peruvian helicopter was landing, had another encounter with the forces of "Tormenta". Again after a short fight, they withdrew.

Meanwhile, the Ecuadorians located "Roosevelt's helipad at the headwaters of the Cenepa and planned an overwhelming attack. On January 24, 80 men from the Ecuadorian Quevedo Special Forces detachment divided into four patrols of 20 men each, left Tiwinza and began a two day march in search of the Peruvian "Roosevelt" patrol. They located the Peruvians on the morning of January 26. They immediately prepared to attack as the "Roosevelt" helipad represented a threat to the rear of the main Ecuadorian position at Tiwinza and one of the main logistical routes and lines of Communication from Patuca.

The Capture of Helipad "Roosevelt"

During the morning of January 26, the "Tormenta" patrol at their helipad observed the coming and going of numerous Super Puma helicopters carrying 120mm and 81mm mortars from Coangos to Tiwinza and Base Sur. There were six helicopters, one Bell and five Super Pumas. The Tormenta patrol observed that the Bell would go ahead as a reconnaissance machine, and once it was clear, the Super Puma's would go in carrying their cargo.

The Peruvians appear to have planned their own attack. Noticing the Ecuadorian's activity at Coangos, they ordered their two Mi-25 Hind helicopters to attack Coangos to prevent fire on Peruvian troops. However, the Mi-25s were not fuelled, so an Mi-17 lifted off from Jimenez Banda to carry out the mission. However, when they arrived over the target area, it was clouded over.

The Ecuadorians struck first, Before dark on January 26, the Bell hovered over the "Roosevelt" patrol. Then it retreated and the five Super Puma's, now armed with machine-guns and rockets began to rocket and strafe the patrol's position. This was followed by 81mm and 120mm mortar fire, and when this was lifted, the 80 men of the Quevedo group opened fire with four machine-guns, LAW anti-tank rockets and rifle fire. They fired for ten minutes and then assaulted. The Peruvian Lt. "Roosevelt" and two other Peruvian soldiers were killed. The rest fled into the jungle. The Ecuadorians took possession of this helipad and named it Base Norte.

Cueva de los Tayos

The loss of this position really stung the Peruvians, and they immediately began planning a retaliatory attack. The Peruvian High Command ordered BIS 25 to assault Cueva de los Tayos. There were already several BIS 25 patrols around this position, "Tono", "Lince", "Espartaco", "Cebra" and "Rommel". There was some urgency as the patrols had observed the Ecuadorians laying mines. At 5:30am on January 27th, the Peruvian patrols, "Cebra", "Espartaco" and "Tono", assaulted the huts at Cueva de los Tayos. After three and a half hours of combat, the Ecuadorians withdrew, supposedly leaving behind nine dead. At least one Peruvian officer and soldier were wounded. However, the Ecuadorians only abandoned the immediate position and continued in the surrounding area, using ambushes, and launching probing and harassment attacks with small arms and mortars. They also set up mines along the footpaths and made punji pits. These would become the characteristic tactics of the Ecuadorians throughout the war. The Ecuadorian forces avoided direct confrontation with Peruvian forces.

They withdrew in the face of heavy attack, but only out of the immediate area. They used artillery, mines, snipers and ambushes to harass the Peruvian troops in their former positions and would then seek to infiltrate back into the area at the first opportunity. These guerrilla tactics were highly frustrating to the Peruvians and caused many casualties. They were probably responsible for the fact that throughout the war the Peruvians would announce that they had taken a position, only to continue announcing that they were continuing to fight in the same location. For example, it was not until three days later that the Peruvians could claim they had consolidated Cueva de Los Tayos. On the 28th of January, a Peruvian Air Force Twin Bell 212 helicopter was hit by machine-gun fire as it flew over the combat zone.

One of the crew was wounded and the fuel tank was punctured. Also, the "Tormenta" patrol up on their helipad was heavily shelled throughout the night by mortars and artillery. Meanwhile, the "Tormenta" and "Cebra" patrols moved from Cueva de los Tayos toward Base Sur to begin the assault on this position.

On the morning of the 29th, the Peruvian Air Force struck Coangos. Two Mi-25s, an Mi-17 and an Mi-8T made multiple rocket and strafing runs. When Ecuadorian aircraft were detected taking off from their bases to intercept the helicopters, they retreated. Around mid-day, the same four helicopters went to make further attacks around Tiwinza in an effort to support the remainder of the "Roosevelt" patrol which was making its way back toward Peruvian lines. However, the Ecuadorians had set up a surprise of their own. Near the target area, one of the helicopter pilots saw a red ball streak toward the lead helicopter, the Mi-8T. It was a missile!

The Mi-25s fired diversionary flares, but the missile was not headed toward that machine. The missile struck the lead helicopter just as the pilot received warning from the Mi-17 pilot. Nothing could be done as the Mi 8T helicopter erupted into a ball of fire killing the three crew. As the other helicopters made evasive manoeuvres and tried to hit the deck they were greeted by machine-gun fire from the ground. The surviving helicopters returned, shaken, to their base.

Base Sur

On the 28th of January, a company or so of the 113th Armored Cavalry Regiment (RCB 113) was sent to Cueva de los Tayos to assist in the consolidation of that position and to relieve elements of BIS 25 that had been in the jungle over 45 days straight. On the same day eight patrols of the 19th Commando Battalion (BC-19) arrived at PV 2. The next day they moved up to PV 1. Three patrols were sent to conduct missions around Tiwinza and five patrols, plus elements of the RCB 113 were immediately sent to Cueva de los Tayos with the mission of attacking Base Sur. When they reached Cueva de los Tayos at 8:30 on the 30th, much to their surprise they met Ecuadorian troops that had re-infiltrated and again taken possession of the position. The BC-19 spent much of the morning driving out the Ecuadorians. After this was accomplished they searched the area and found fourteen rotting Ecuadorian bodies, probably most from the battles on the 27th and 28th.

While elements of the RCB 113 were left to consolidate Cueva de los Tayos, the five patrols of BC-19 and a patrol from RCB-l13 continued on to Base Sur. An error on the Peruvian map got all the units lost and instead of reaching Base Sur, they ended back up at Cueva de los Tayos. Using their GPS locators, the commandos corrected the errors on their map and set out again on January 31st. That evening they set up an advanced reconnaissance base on the western slope of hill 1406. They began to reconnoitre toward the Ecuadorian positions along a trail, and immediately ran into mines. One man lost his foot and the commandos returned to their patrol base to spend the night and plan their attack.

The next day, to avoid the mines they advanced up a meter deep creek under a light rain. As they advanced they found a little used trail with fresh foot prints. Two NCO's advanced up the trail to conduct a reconnaissance. 150 meters up the trail, the men ran into Ecuadorian bunkers with machine-guns and exchanged shots. The men returned to the stream and reported. The commandos sent a strong patrol of volunteers up the trail to take out the bunkers. If possible, they were to use silenced weapons that they carried. Instead they were ambushed by the Ecuadorians with sniper rifles in the trees. The lead officer of the patrol was killed. The patrol retreated.

The Peruvians decided that instead of the direct approach, they would first outflank the position and take the high ground behind Base Sur and cut off the trail to Coangos to prevent reinforcements from that side. Two commando patrols and one patrol from RCB-113 set out to take the heights behind Base Sur. Three other commando patrols set out to cut off the trail to Coangos. It took a four hours of constant firing and advancing to take the high ground behind Base Sur. The next day, February 3, the Commandos, having taken the flanks, now turned inward and attacked using everything they could including RPG-7s, rifle grenades, M-203 grenade launchers and MAG machine-guns.

This attack began at 7am. At 7:45, the Ecuadorians called in air support and Super Puma helicopters rocketed and strafed the positions of the attacking Peruvians. This was followed by mortar and light artillery fire. Six Peruvian soldiers, probably from RCB-113 or BIS-25 were killed, and an undetermined number wounded. At 11am Ecuadorian reinforcements came down from the Coangos base, and ran into the blocking positions of the Peruvian commandos. The Peruvians drove them off claiming 8 Ecuadorians killed.

By noon, the commandos had taken Base Sur and beaten off the reinforcements from Coangos. The Peruvian Commandos suffered eight wounded and two killed by mines. They captured nine bunkers and various types of equipment. However, although there was a helipad, the weather conditions did not permit the evacuation of the wounded by helicopter. The commandos left RCB-113 at Base Sur and withdrew to Cueva de los Tayos. On February 4th, the Ecuadorians blanketed Base Sur and Cueva de los Tayos with artillery fire, mostly from Coangos. Fire was particularly heavy on the southern side of both Base Sur and Cueva de los Tayos. Under cover of the bombardment, the Ecuadorians infiltrated patrols that conducted harassment and pin-prick attacks. This caused a number of dead and wounded to the Peruvian troops in this area including the Commandos and RCB-113. That afternoon, the Peruvians detected some Ecuadorian mortar batteries on Hill 1666 just in front of Coangos. A squadron of Mi-25s were sent to silence the position. According to the Peruvians, this mission was accomplished successfully.

Tiwinza: Phase 1

Cueva de los Tayos and Base Sur were relatively easy operations compared to what was to come. They had just been advanced positions on the south and eastern flanks of Tiwinza. Tiwinza is a small elevated plain. It is surrounded by hills. This area, a total of 15 square kilometres was completely fortified, surrounded by minefields and defended by an estimated two battalions of Ecuadorian troops according to Peruvian sources. While elements of BC-19, RCB-113 and BIS-25 fought for Cueva de los Tayos and Base Sur, other elements of BC-19, and BIS-25, began approaching Tiwinza. The Peruvian patrols "Tormenta", "Rommel" and "Lab" from BIS-25 attempted to advance on Tiwinza but were stopped by mortars and mines. On February 1 "Tormenta" and "Lab" had fire-fights with the Ecuadorians. "Lab" had two and "Tormenta" one. These fire-fights continued and on February 2, a Peruvian officer was killed. During February 4th the fire-fights continued.

In the afternoon, the "Rommel" patrol captured five LAW rockets and a radio in one fight. On February 5th, at 11:00pm, "Lab" conducted an attack they claimed caused 22 Ecuadorian dead. On February 6, the Ecuadorians attacked the Peruvians with Super Puma helicopters. Meanwhile they sent flights of RPVs overhead to locate the Peruvian patrols. At 6am on February 7, the Ecuadorians launched a mortar barrage that wounded four men of the "Lab" patrol.

Ecuadorian Retaliatory Raids

The Ecuadorians retaliated with preventive strikes. Up until that time, Ecuadorian artillery and air attacks had been directed at Peruvian troops in and around the former Ecuadorian positions of Cueva de los Tayos and Base Sur. Now they were concentrated on recognized Peruvian territory. On February 7, mortar barrages struck near PV l, PV 2 and PV 12. Meanwhile Ecuadorian troops from Condor Mirador, Potero and Zumbi sent patrols near PV 1 to harass the communications and logistics lines. Ecuadorian planes launched bombing attacks on PV l and Cueva de los Tayos. One air raid on PV 1 shortly after 1pm caught the Peruvian troops out in the open, getting organized. To add insult to injury, an Mi-25 helicopter was shot down by an anti-aircraft missile over the Tiwinza area killing all three of the crew. The Peruvians retaliated with an air raid of their own on Coangos.

On February 8th, the Ecuadorian deep strikes continued hitting PV 1, PV 2 and PV 12 with mortars, light artillery and BM-21 MLRS. They also hit Cueva de los Tayos and Base Sur. Just before noon, the Ecuadorian air force planes again bombed PV 1. On February 9 they continued their artillery barrages against PV 1 and Cueva de los Tayos. The Peruvians attempted to retaliate. That evening, the Peruvians carried out bombing mission over the valley with Canberra B(I) 68s. The next day, February 10, two squadrons of SU-22 fitters and an A-37 Dragonfly made raids against Tiwinza. The Fitters hit Tiwinza.

According to the Ecuadorians, two Mirage FIJE's from the 21st Fighter Group scrambled from Taura air force base established a combat air patrol at 17,000 feet over the combat zone. The first Mirage acquired an unidentified aircraft at 6-7 miles on his radar screen. After making a positive visual identification on two Peruvian SU-22 Fitters he locked on the closest Fitter and fired a Magic air to air missile. He then broke sharply and dived before the missile hit its target. As he did, the second Fitter turned towards his Mirage, but his wingman fired a Magic Missile which also hit its target. The Peruvians admit losing the two planes, but claim that both were brought down by anti-aircraft missiles, not air to air missiles. Because of the lack of detail and vagueness of the Peruvian account, the Ecuadorian version is probably correct. Later that same day, a pair of Kfir 2C detected the Peruvian A-37 and came in for the kill. One of the Kfir's fired an air-to-air missile which struck the A-37 in the tail, both of the crew managed to eject and after several arduous days in the jungle, make it back to Peruvian lines. The shooting down of three Peruvian aircraft by Ecuadorian aircraft without any reciprocal losses has caused the Ecuadorian Air Force to make February 10th the day of the Air Force.

Tiwinza: Phase 2

Meanwhile the Peruvians renewed their assault on Tiwinza. They had brought up new forces, particularly several counter-subversive battalions from Huallaga, Naval infantry and Paratroopers. This included a paratrooper artillery battery "Bravo" of Oto Melara 105mm pack howitzers. The new strategy was to use the counter-subversion troops to attack Tiwinza from the front, while the special forces would strike the enemy deep in his rear and flanks. On February 12, battery "Bravo" opened fire for 30 minutes just before dawn to support the Peruvian advance. The Ecuadorians responded with volleys of BM-21 rockets from Mirador and 105mm artillery fire from Banderas.

Finally, Ecuadorian aircraft came in to bomb the position. One Ecuadorian A-37 was hit by a SA-7 Strella missile, but managed to limp back to base and land safely. The bulk of the assault on Tiwinza was carried by BIS 314, Counter Subversive Battalion (BCS) 16, and Special Commando Company (CEC) 115.

Deep Raid Against Coangos

On February 12 the commandos passed through the positions of parachute battalion (BIP) 61 at Base Sur. There were 193 commandos of BC-19 and 17 naval commandos of the FOES, divided into seven patrols of 30 men each set out to conduct a raid against Coangos. They decided to set up an ambush on the trail just outside the main entrance.

On the afternoon of February 13th they reached their position and were just finishing setting up when a group of approximately 80 Ecuadorian soldiers came down the wooden stairs from Coangos. They did not suspect the Peruvian ambush and came forward as if nothing were happening. When the lead Ecuadorian was five meters away from the front end of the ambush position, the Peruvian machine-gunner opened fire. Peruvian RPG's, rifles, rifle grenades and hand grenades joined in. According to the Peruvians, the lead 30 to 40 Ecuadorian soldiers were completely annihilated. The rest deployed and returned fire. Ecuadorian mortars opened up and further groups of Ecuadorian troops deployed from Coangos to attack the Peruvians. The Peruvian commandos responded with 47 RPG rockets, 270 M-203 grenades and 18 Instalaza rifle grenades. Ecuadorian mortars joined in and finally Super Puma helicopters.

The arrival of the reinforcements forced the Peruvians to withdraw, carrying with them 1 killed and 18 wounded. Three Super Puma helicopters came out in search of the commandos, but they hid in the dense jungle and waited for the helicopters to give up the search before moving.

Meanwhile the 16th, 314th counter-subversive battalion and the 115th Special Commando company left helipad Tormenta to assault Tiwinza. BCS-16 was on the left flank, BCS-314 in the center, and CEC 115 on the right flank. They took up positions in front of Tiwinza on February 17th. Some probing action was carried out with Peruvians approaching Ecuadorian held positions and firing RPG-rockets, rifle grenades and grenade launchers at the Ecuadorians and then withdrawing. On the morning of February 18th these three units began their attack. The attack stalled as the Peruvians ran into minefields and the Ecuadorians rained artillery down on them.

At the individual positions, the Ecuadorians responded with rifle grenades and large quantities of grenade launchers. The Ecuadorians were deeply entrenched in bunkers and trench positions. The 28th counter-subversive battalion had taken the place of the 314th battalion at helipad Tormenta.

To support the attacking units, the 28th formed "Company B." This ad hoc unit was formed to provide close in support for the assaults on the fortified Ecuadorian positions. 11 RPG-7 launchers and 220 rockets were concentrated in this one unit along with machine-guns and rifles to protect the rocketeers flanks. On February 21, company B reached the front line just north of the Y. The Ecuadorians launched a raid and on the night of the 21st called down artillery, which fired all night long at the Peruvians. On the 22nd, the Ecuadorians attacked with artillery and aviation, bombing and strafing the Peruvian positions. Company B advanced and from a higher elevation saw Ecuadorian soldiers building a fortified line, digging trenches and building bunkers.

At that moment, another fire-fight began, apparently an Ecuadorian ambush against men of BCS-16. To provide support, the commander of Company B ordered his RPGs to line up and fire. Two RPGs fired simultaneously followed closely by the other nine. The effect was tremendous. Anywhere the Peruvians heard noise they fired RPGs. While the RPG's were reloading, the machine-guns fired providing cover.

However, despite the beating, Company B did not advance and take the trench line. At the end of the day, Company B was down to 12 RPG rockets. They had fired over 200 rockets in a single engagement. That night, 90 men of RCB 113 moved up to support. The Ecuadorians again gave the Peruvians their daily dose of artillery fire. The Peruvian advance apparently stopped shortly after this as no more advances were reported until the cease-fire. On February 24th, the RCB-113 killed three Ecuadorians and presented their military I.D.s to the press as proof.

Deep Attack against Tiwinza

While the BCS-314, BCS-16, the CEC 115 and "Company B" BCS-28 made a frontal attack on Tiwinza, the commandos of the 19th Battalion went around the flanks and into the rear of the position. On February 22, the commandos discovered an Ecuadorian mortar battery firing away at the advancing Peruvian troops. Part of the Peruvian troops attacked the mortar position, killing 12 Ecuadorian soldiers and capturing some 81mm mortars, 60mm mortars and several FAL rifles. A Peruvian commando patrol providing security to this attack to the north ambushed a group of Ecuadorian soldiers bringing supplies down the trail and killed another 9 Ecuadorian soldiers. During this attack the Ecuadorians confused the back blast of the RPGs for flame-throwers. The Peruvian commandos picked up their captured gear and began to withdraw. On February 23rd, another Peruvian commando patrol that had been left on the trail into Tiwinza to provide ecurity for the group that had carried out the raids of the 22nd, ambushed another Ecuadorian patrol, killing 7 and wounding 2 others. They captured FAL rifles, an RPG rocket launcher and grenades and night vision scopes. On the way back to Peruvian lines, one commando patrol ran into some mines, which wounded their lead scout. Later that same patrol was ambushed by the Ecuadorians and suffered two wounded.

Casualties

The Peruvians claim to have killed 180 plus Ecuadorians. They admit to losing four times as many men as the Ecuadorians did, This would imply that the Peruvians lost 720 killed and an undetermined number of wounded. This seems very excessive to me. The figure of 180 killed is probably much exaggerated. 90-100 killed seems much more reasonable, putting Peruvian killed at somewhere between 360 to 400. The Peruvian killed still seem somewhat excessive, but much more reasonable than the elevated figure cited earlier. This is also much more in line with the number of units involved in the fighting. The following Peruvian ground units have been identified as participating in the war:

- 5th Jungle Infantry Division

25th Jungle Infantry Battalion

19th Commando Battalion

113th Armored Cavalry Regiment

85th Jungle Infantry Battalion

28th Counter-subversive Battalion

314th Counter-subversive Battalion

5th Porters Battalion

Naval Commandos

61st Parachute Infantry Battalion

16th Counter-subversive Battalion

30th Counter-subversive Battalion

32nd Counter-subversive Battalion

115th Special Commando Company

39th Parachute Infantry Battalion

31st Naval Infantry Battalion

32nd Naval Infantry Battalion

Bravo Parachute Battery

Air Force anti-aircraft missile operators

If the average unit size (battalion) was 500, with a few adjustments this means approximately 8,000 ground forces in the area of operations. Not all were there at the same time, and not all of the companies of each battalion were forward at the same time. If we estimate that a third of these forces were in the combat zone at any one time after February 1 (the time of the most intense fighting) we are looking at a force of 2,700 to 3,000 at any one time. Probably in the early part of the conflict it was around 1,500 and toward the end around 5 or 6,000. If the Peruvians lost 720 men, then the death rate was 10%, the total casualty rate unknown, but one an estimate about 2 or 3 wounded for every man killed. This would equal a total wounded number of between 1400 and 4300. This is too excessive for the number of forces committed. The lower casualty figure is probably nearer the truth for Peru, if not even lower. At 360 killed, Peru would have suffered between 700 and 1,000 wounded. This is still excessive for the number of forces committed. My guess is that somewhere between 90 and 100 Ecuadorians were killed and between 200 and 250 Peruvians killed. This would still put Peruvian wounded at around 400 to 750 wounded. No matter what the truth, this war was far bloodier than the 1981 conflict.

Uniforms and Equipment

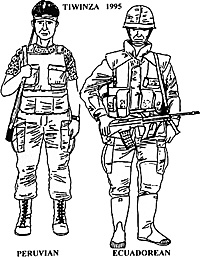

All Peruvian soldiers were dressed in a yellow green uniform and cap. Although Peruvian commandos wore camouflaged BDU uniforms, the use of this same uniform by the Ecuadorians dictated that the commandos wear the yellow-green uniform of the normal army. The cut of the uniform resembled the American BDU uniform, but the color resembles the Israeli combat uniform, perhaps a little lighter. Underneath the jacket, Peruvian soldiers wore a beige T-shirt with brown or black camouflage spots.

The preferred mode of dress seems to have been to just wear the T-shirt and pants, with the pants often cut off to make shorts. Often rubber boots were worn with these uniforms in place of the jungle boots, but not always. No helmets were seen except for some Israeli fibre helmets were worn by the Peruvian artillery crews, but not by other troops. Sometimes a light body armor vest was worn with two chest pouches and three or four waist pockets to carry various items of equipment. The pockets were about the right size to carry the 20 round FAL magazines carried by most regular troops. Peruvian troops carried their equipment in an Israeli designed H-harness, usually with two magazine pouches, one or two canteens, and a hand grenade pouch. These were in Khaki sand color. The standard rifle of the regular troops was the EN FAL. Support weapons included the Instalaza rifle grenade, the EN MAG machine-gun and the RPG-7 rocket launcher. Hand grenades rounded out the collection.

Peruvian commandos usually carried 5.56mm Galil or South African equivalent R-4 rifles instead of the FN-FAL. For support they carried M1 6/M203 combination weapons, rifle grenades, FN-MAG machine-guns and RPG-7 rocket launchers. Other than the individual weapons they carried, Peruvian troops were dressed alike. The Ecuadorian front line soldiers generally wore an American BDU camouflage uniform and carried an M-16A2 rifle or HK-33 rifle. About 10% of both types of rifle were seen fitted with the M-203 grenade launcher. Some South African MGL-40 multiple grenade launchers were also seen. Rifle grenades were also used. Second line troops carried FN-FAL rifles both in the full stock and folding stock versions. Some special forces troops carried Steyer Aug bullpup rifles. Anti-tank weapons carried by the Ecuadorians included M72A2 LAW disposable rockets and some form of RPG weapon. For heavier support there were EN MAG machine-guns and .50 caliber machine-guns. Indirect weapons included 60mm Tampella mortars, 81mm and 120mm mortars.

Ecuadorian soldiers usually wore their uniforms complete with tunic, M-1 steel helmet ( a few Israeli fibre helmets) and commonly, body armor. There were a number of types of armor vests, some with British DPM pattern covers, and some of Israeli origin with integral magazine pouches and butt pack. The average front line soldier was equipped with a copy of US Alice gear, nylon Y harness and magazine pouches with plastic quick release fasteners. Second echelon soldiers equipped with FN FALs carried Israeli designed harness and magazine pouches, similar to those used by the Peruvians. Israeli Galil harnesses and equipment vests similar to those manufactured by the Eagle company in the United States were worn, often by special forces or elite troops.

The Ecuadorians were well equipped with night vision devices, while the Peruvians did not have as many. While both sides were equipped with anti-aircraft missiles of Soviet design, the Peruvians had the old SA-7 Strella, while the Ecuadorians were equipped with the SA-16 or better. The Ecuadorians also generously used mines and booby traps. This was extremely frustrating to the Peruvians and was probably singly responsible for holding up the Peruvian advance. In addition, the Ecuadorians were supplied with artillery that the Peruvians couldn't match.

The Peruvians enjoyed 81mm and 120mm mortars and some Oto Melara pack 105mm howitzers, but not in the quantities enjoyed by the Ecuadorians. In addition, the Ecuadorians could blanket the whole conflict zone with artillery fire that was directed by RPVs which accurately located new Peruvian deployments. The Peruvians complained that most of their casualties were caused by mines and artillery and not in direct combat. This was true, but what they don't say is that because of this, less troops reached the front line, and those that did were in a less than ideal state.

On top of the disparity in weaponry, the Peruvians had logistical problems of all kinds. Food and ammunition was scarce, and casualties often had to be evacuated part way by foot. There were not enough helicopters to go around, and the anti-aircraft defences of the Ecuadorians kept Peruvian aircraft out of the combat zone. In contrast, the Ecuadorians had much shorter and more secure lines of communication and supply and enjoyed far greater quantities of food and ammunition.

The Soldiers

In general, the Peruvian troops were of superior quality than the Ecuadorians. This was not from lack of training, but rather, lack of experience. Most of the Peruvian officers had been in combat with the MRTA or Sendero Luminoso guerrillas, often on similar terrain, and many of the troops as well. The troops used to attack Tiwinza were the counter-subversive battalions and the commandos, those with the most combat experience. Some of the men in almost all of these latter units were turned terrorists. Despite their disadvantages in communications, logistics and technology, the Peruvian soldiers fought well. The Peruvians took the relatively lightly fortified and defended Cueva de los Tayos and Base Sur in fairly short order, although they spent more time consolidating the positions because of Ecuadorian tactics. However they did not take the much more heavily fortified and stubbornly defended Tiwinza. They did take some of the positions around Tiwinza and managed to send commando patrols in deep that carried out at least two fairly devastating strikes. The Peruvian soldiers should not hang their heads in shame, they fought well with the means they had.

The Ecuadorians also fought with skill, their main disadvantage being their lack of experience. They showed much innovation with what they termed "guerrilla tactics." These surprised the Peruvians and caused them no end of headaches. The Ecuadorians conducted hit and run attacks, ambushes and harassment. They did not defend minor positions except briefly, having mined and booby trapped their routes of retreat, and then stood outside and harassed the Peruvians occupying the just vacated position. The recently vacated positions were then saturated with artillery fire and at the first opportunity, the Ecuadorians would infiltrate back in, forcing the Peruvians to clean out two and three times, positions they thought they'd taken.

The Ecuadorians showed flexibility by also being able to defend well prepared, fortified positions. These consisted of trench lines with log bunkers containing heavy weapons. The positions were surrounded by mines and booby traps. These were very difficult to take and very difficult to locate until the Peruvian troops were right on top of them. A favourite weapon for breaking through this type of position up close was the RPG-7. The Peruvians also made locally improvised bangalore torpedoes to break through the mine fields and to blow new trails through the jungle.

The Peruvians entered the conflict with the mentality of the last skirmish. They thought they could set up their helicopter pads in strategic positions and repeat their success of 1981 of overwhelming the Ecuadorians with heliborne infantry assaults using a minimal commitment of men and resources. They were in for a rude shock, one that they recovered from, but not in time to secure victory. The Ecuadorians can rightly claim victory in this third Peruvian-Ecuadorian war. They held terrain and inflicted heavy casualties at a much lighter cost to themselves. They overcame their humiliation of 1941 and 1981, but it was no cake walk. Both sides fought long and hard. The next clash, if there is one will likely be greater than the 1995 war as both sides will have something to prove.

( Good to see that David keeps the society up to date details of modern conflicts in Latin America, my experience of trying to obtain details of this war, while it was happening and after, have not been a success, very few U.K. newspapers carried any information on it at all, if I was lucky then I might just see a couple of paragraphs which told me very little. No doubt U.S. newspapers were much the same, as for articles in military journals I have not been told of any or seen any, but there must have been some report or article published, other than by Peru or Ecuador, which again I have not seen. All of this lack of data makes this article, for me, a welcome addition to my files, thank you David. T.D.H. )

Large Illustration Uniform Figures (slow: 86K)

Back to Table of Contents -- El Dorado Vol VIII No. 3

Back to El Dorado List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by The South and Central Military Historians Society

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com