His Majesties' Sailing Rules (HMS Rules) are a set of quick naval rules from the age of sail. They are intended to be used to play single ship actions and squadron actions from 1650 to 1820. They show case the uses of the calculated risk idea presented in EGG #23.

His Majesties' Sailing Rules (HMS Rules) are a set of quick naval rules from the age of sail. They are intended to be used to play single ship actions and squadron actions from 1650 to 1820. They show case the uses of the calculated risk idea presented in EGG #23.

CALCULATED RISK

What is a calculated risk? This is a vital question since the following set of rules are centered around this one idea. The answer is obvious, really. A calculated risk is just that. It is a risk that one chooses to take that involves danger and reward. The player/general decides/calculates how much risk he wants to take versus the amount of risk he will face. That's the simple answer.

In life we make calculated risks all the time. When I am driving down the highway at 60 MPH (where the speed limit is 55 MPH) I am taking a calculated risk that any police I run across will not pull me over. I am very likely to get away with this risk. But what will happen if I push it a little further, say up to 65 MPH? What about 70 MPH? 80 MPH? Eventually I will push it too far and get nailed.

Battle situations parallel such like experiences in many ways. For instance, how long can an army go without food before it is no longer an effective fighting force? What about pay? How long will men stay loyal to an army that is in arrears in pay? How long can a unit be kept in continuous combat before its men crack up? All of these occurrences call for the leader to make calculated risks about what he thinks he can get away with. So how can a calculated risk be done in a game? Well in fact they already are. The idea of balancing risk with reasonable gain has been in gains from Tactics II in the 1950s.

The combat factor odds result table (1d6 rolled on an odds column based on relative strength of the two sides) is clearly a calculated risk. The trouble with this calc risk is that it is too simple. Number gamers figure out in 5 minutes that you have to be a fool to fight at 1:2 odds. In effect this calc risk allows players more control over the battle outcomes than ever exists.

Chainmail used a 2d6 combat system that took account of a calculated risk by making it easier for unarmored men to be hit. It also judged the relative effectiveness of weapons compared to armor. Obviously a unarmored man with a dagger was at great disadvantage compared to a man in plate armor with a two handed sword. Again there is a weakness. One would have to be a fool to want to play an unarmored man with a dagger! They aren't really choices since to chose the first option is suicide.

My approach to calculated risk is to allow the players to roll as many dice as they wish. 6's score hits against the enemy, BUT 1's score hits against the firer! So go ahead a roll 20 dice. That may well blow away the enemy in front of you, but it is just as likely to destroy your own men at the same time.

I presented this ideas in EGG 23. I know that it doesn't make a whole lot of sense to people as it stands. To rectify this I've written the following set of rules that apply these ideas. DESIGN GOALS

I would like HMS Rules to achieve a few goals...

- 1. They are to apply the calculated risk idea so that other gamers can understand what I am talking about.

2. They should allow inexperienced players to game single ship actions in 10 to 15 minutes, without excessive referee involvement.

3. Squadron level actions should be able to be played out in 30 minutes.

4. Record keeping should be kept to a minimum.

5. The game should have the look and feel of a "Ship of the Line/ Wooden Ships Iron Men" game.

6. It should yield results that roughly parallel historical accounts of ship actions.

7. And finally, if most of the above requirements are met, it should be able to be used to resolve battles in a 4 hour convention naval MG campaign game! (Really my primary goal)

HMS Rules appears to meet these goals.

PHYSICAL COMPONENTS

1 sheet of Blue vinyl cloth with 1x1 inch squares drawn on it (a 30x30 grid should do but a 90x90 grid is better)

12 six sided dice

10 or so miniature ships 1 inch long

paper and pencils

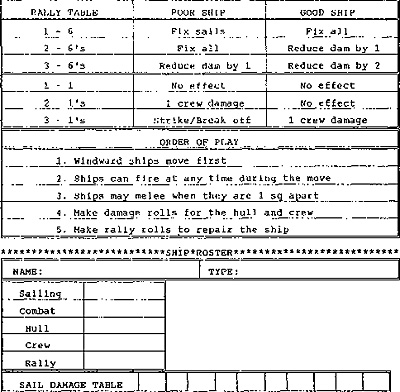

ORDER OF PLAY

1. Windward ships move first (ties are settled by comparing ship size and sailing quality)

2. Ships can fire at any time during the turn

3. Melee occurs when ships are 1 square apart (ie next to one another).

4. Make damage rolls.

5. Make rally rolls.

This order of play is pretty standard to most games. The only differences might be in that the most windward ships move first. This gives them the weather gage advantage. But sneaky little maneuvers like sliding in behind someone do not work since ships can fire at any point during their turn. If a ship moves across another ships line of fire then they can fire. This makes it easy to shoot and difficult to evade being shot. Damage rolls and rally rolls involve keeping the ship afloat.

DICE ROLLS

The calculated risk idea allows players to roll "as many dice as they want to." Obviously this could get stupid, since it would encourage Lebanon style suicide attacks. The HMS solution to this is to have a set number of dice on the board. In this case there are 12 dice out. The player chooses how many of these he wishes to roll.

Calc risk dice rolls always use 6's as positive results and 1's as negative results to the rolling unit.

Risk is rolled for in 1. sailing, 2. combat, 3. damage rolls, and 4. rally rolls. In damage rolls only the negative results matter since the roll is made to determine if a ship sinks or not.

SAILING

Sailing is a difficult thing to simulate in a board game. I've actually never seen a game do it justice (this one included). In yacht racing for instance there is a lot of chance and strategy involved. For simplicity, most games make sailing easy/simple. Calculated risk, keeps sailing easy but adds in a level of uncertainty that makes it anything but simple.

All ships have a base move of 1 square and one turn a turn. So a ship making its base move can do the following...

All ships have a base move of 1 square and one turn a turn. So a ship making its base move can do the following...

To move more than the base move the player must decide how much risk he wants to take. Ships are divided up between good sailors and poor sailors. Good ships move more easily and are less prone to troubles (ie low risk).

Poor sailors are hard to get going and more prone to trouble (ie high risk). It is possible for a poor sailor to out maneuver a good sailor if the captain takes more risk and it pays off.

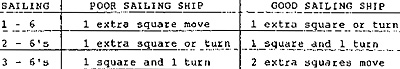

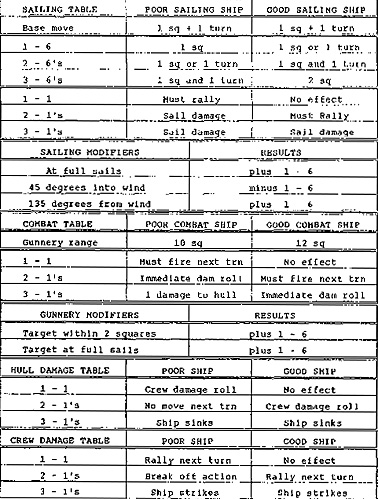

Players roll up to 12 dice on the following table

Players roll up to 12 dice on the following table

If a player tosses 6 dice and rolls 3 - 6's then he could move his ship 3 squares in a straight line (if it is a good sailor) or 2 squares and make 2 turns (if it is a poor sailor). The player may always chose to move at a slower rate in order to get the turns. For example, the above good sailor the rolled 3 - 6's could move at the 2 - 6's rate (2 sq and 2 turns) in order to maneuver.

Rolls to move also may yield problems if ones are rolled.

Rolls to move also may yield problems if ones are rolled.

Ships can begin to have problems if only 1 - 1 is rolled (if it is a poor sailor). The first problem that is likely to occur is for the ships crew to fall into disorder. A rally roll in the next turn will fix this (regardless if any 6's are rolled). Disorder only ties up a crew for one turn. Sail damage on the other hand is more serious. A sailing ship is really nothing more than a bunch of wood, rope, and canvas put together in a certain way.

If the ropes are out of place, then the sails don't work right. Lose lines or worse broken lines are just as much of a problem. So ships with sail damage may only make their base move until their sails are repaired (see fix sails and fix all in the rally section). So you can see that since poor sailors are so prone to sail damage they are much more likely to move more slowly.

Sailing is modified by only 2 things: what facing a ship is into the wind and whither it has full sails up or not. Since the game is about sailing ships, no forward movement can be made if a ship starts its turn pointing into the wind. But if ships have movement and turns they may tack across the face of the wind.

If a ship is 95 degrees into the wind then it gets a minus 1 - 6 on any sailing rolls it makes. So if a ship scores 2 - 6's then it would lose one of them. If a ship is running 135 degrees away from the wind then it gets a plus 1 - 6 to its move. This only applies if a ship scores at least 1 - 6 in its roll. A ship at full sails also gets a plus 1 - 6 to its move (if it scores at least 1 - 6 in its roll).

- SAILING MODIFIERS : RESULTS

Sailing 45 degrees to wind : minus 1 - 6

Sailing 135 degrees to wind : plus 1 - 6

Sailing at full sails : plus 1 - 6

If a ship for some reason gets stopped pointing into the wind, it is caught in irons. It loses its base move. It must make a sailing roll to try and get out of this. What they are doing is back sailing to gain a turn to reposition the ship. If the ship gains a turn it may make it in place to be able to sail off the next turn. A ship can not make this turn and move off (even though its sailing roll may have given it extra move). That is the penalty of getting caught facing into the wind.

Ships may move and turn as they wish. But I recommend that ships not be allowed to move and then turn 90 degrees. It would be better for the ship to turn first in its starting square, move a square and then turn again. I don't want to put an out right prohibition on this though since small ships (sloops and brigs) probably could do this.

COMBAT

Naval combat is the purpose of these rules. It is handled in almost the same way sailing is done. Combat is divided into 2 types: gunnery and melee.

Ships are divided up between ones that are good in combat (like ship of the line and frigates) and ones that are poor at it (like sloops and merchant ships). A ships fighting quality applies both to gunnery and melee.

GUNNERY

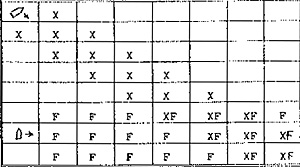

Ships in the age of sail lined their cannon along either side of the ship. Thus the term "broad side" of fire. The trouble with this arrangement is that it greatly restricts the ships arc of fire. Ships basically fire straight out away from either side of the ship. HMS Rules use the following arcs of fire.

Ships in the age of sail lined their cannon along either side of the ship. Thus the term "broad side" of fire. The trouble with this arrangement is that it greatly restricts the ships arc of fire. Ships basically fire straight out away from either side of the ship. HMS Rules use the following arcs of fire.

Gunnery range is based on wither a ship has good or poor fighting qualities. Good ships can fire out to 12 squares. Poor ships can only fire out to 10 squares.

The purpose of gunnery is to pound the enemy ship into submission or to sink it. Consequently gunnery can be directed towards doing crew damage or hull damage. The player chooses which he wants to target. The player then chooses how many of the 12 dice he wants to roll. 6's score hits on the target (see the damage section).

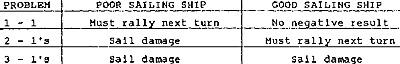

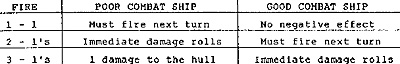

Problems can arise in gunnery when 1's are rolled.

Problems can arise in gunnery when 1's are rolled.

The first problem that always arises in combat is a loss of control over the men. When this happens the ships crew is forced to continue rolling for the gunnery duel (even if the target is out of range!) They are so engrossed in firing and loading that they disregard any orders to stop. If no target is at had, the player does not have to roll any dice but his crew is still allocated to the gun regardless! The next problem that can arise from shooting is the damage it can do to ones own ship. Immediate damage rolls (see the damage section) require the player to check and see if the ship strikes or sinks. In poor ships shooting can actually damage the ship. This is due to cannons breaking lose and from the vibrations of fire. Obviously firing cannon is not as safe as it looks.

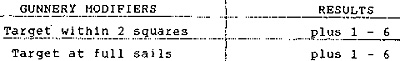

Gunnery is modified by 2 factors: the range to the target and if the target is at full sails. If the target is 1 or 2 squares away from the firing ship then the fixer gets plus 1 - 6 (ie 1 extra hit) to the target.

As with sailing, the firer must first score at. least 1 - 6 in the roll to be able to use this modifier. If the target ship is sailing at full sails the firer also get plus 1 - 6, with the same restriction as above.

As with sailing, the firer must first score at. least 1 - 6 in the roll to be able to use this modifier. If the target ship is sailing at full sails the firer also get plus 1 - 6, with the same restriction as above.

MELEE

When ships are 1 square from one another they may engage in melee. They do not have to do so, but if even one player wants to then they both must do it.

In the age of sail, boarding parties were the climax of battle. Brave sailors armed with cutlasses and boarding pikes. Steady marines firing their muskets from the rigging. Soon the 2 sides threw grapple hooks and the fighting commenced. Melee in HMS Rules is handled just like gunnery, except that only crew are effected (the hull is unaffected by musket shot).

The player chooses how many of the 12 dice he wants to roll. 6's score hits on the enemy crew. While 1's cause problems. The same problem table is used for melee as is used for gunnery, with roughly the same effects.

Ships that must fire again, are forced to melee again next turn. Immediate damage rolls stay the same, as does the 1 damage to hull on poor combat ships.

Ships may chose to stay in melee (or be forced to stay) on subsequent turns. If one side want to break off though, it may do so by sailing away during the movement phase. Melee can be decisive or the prey can elude one at the last minute.

DAMAGE

Sailing ships are remarkable machines. They are capable of sustaining large amounts of damage while still remaining afloat. They have been known to remain in active service for up to 100 years! But they can also be blown out of the water by massed artillery fire.

Ships damage is recorded in two ways: damage to the hull and damage to the crew. Hull damage can cause a ship to sink. While crew damage can cause a ship to surrender.

Each player must keep a running total of his ships damage in these two areas. Each 6 scored by an enemy gun or melee causes 1 hit. The number of hits a ship has in an area tells the player how many dice he will have to roll when damage rolls are made.

If a ship takes more than 12 hits it does not have to roll more than 12 dice for damage rolls, but the extra hits will make it harder to repair the ship while the battle is underway.

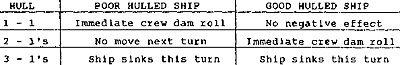

At the end of each turn (and whenever a combat result calls for immediate damage rolls) the player must roll his current damage roll for both the ships hull and crew. The player will not want to roll more dice here since there is nothing good to be gained and much to be lost. Consequently 6's count for nothing in this roll, while 1's count for everything.

Some ships are much larger than others and are able to withstand much more damage. other ships are poor at withstanding damage. Crew and hull abilities may be different due to the size of the crew. For instance, Merchant ships are very large (a good hull tolerance) but have small crews (a poor crew tolerance). Ship of the Line meanwhile are good in both hull and crew.

Some ships are much larger than others and are able to withstand much more damage. other ships are poor at withstanding damage. Crew and hull abilities may be different due to the size of the crew. For instance, Merchant ships are very large (a good hull tolerance) but have small crews (a poor crew tolerance). Ship of the Line meanwhile are good in both hull and crew.

As noted above loss of order is the first potential problem that can arise as a ship begins to sink. The immediate crew damage roll can cause a ship to strike, so that the men can get down to the real Job of saving the ship. Poor ships can be so damages as to be dead in the water for a turn. And lastly, of course a ship can sink. (see rally section on how to stop a ship from sinking).

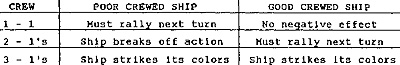

The first problem arising in crew damage is disorder. The ship must make a rally roll on the next turn to fix this. No 6's need to be scored to reorder the men but they might be needed to fix some of the damage that is obviously present: Poor crewed ships may decide to break off an action. If this happens then the player must move them away from the fight. If they are pursued they still may have to fight, but they will not voluntarily move back into gun range. Finally a ship can strike its colors (ie surrender). A surrendered ship must sit and wait to be boarded the enemy. All that they may do until then is to try to fix the ship (see the rally section).

The first problem arising in crew damage is disorder. The ship must make a rally roll on the next turn to fix this. No 6's need to be scored to reorder the men but they might be needed to fix some of the damage that is obviously present: Poor crewed ships may decide to break off an action. If this happens then the player must move them away from the fight. If they are pursued they still may have to fight, but they will not voluntarily move back into gun range. Finally a ship can strike its colors (ie surrender). A surrendered ship must sit and wait to be boarded the enemy. All that they may do until then is to try to fix the ship (see the rally section).

RALLY

When the crew is in disorder and the deck is covered with debris, the bowson calls out "Avast you swabs! Clear the deck!" The officers can then instruct the men on what they want done next. Holes can be mended, and wounded attended. The end result is that the ship returns to a state of order, it just takes time. Yet rallying a ship is not also without certain risk. In the thick of combat it might send the crew the wrong message if a majority of their members-were put to manning the pumps! They might start getting the idea that they had lost or something. And we don't want that to happen, do we?

Rally rolls can fix the ships sails, rally the men, keep a sinking ship afloat, and even reduce the ships total damage number. The player decides how many of the 12 dice he wants to roll. 6's will help him, while 1's hurt.

Ships have varying abilities to effect damage control. Good damage control is the hallmark of a large well manned ship. Smaller ships do a poorer job due to lack of man power.

Ships have varying abilities to effect damage control. Good damage control is the hallmark of a large well manned ship. Smaller ships do a poorer job due to lack of man power.

Damage control can most easily fix what was most easily caused. Sail damage occurs frequently so it requires only 1 - 6 to fix. Other damage (like sinking!) is a little harder to fix. The fix all result means that the ship is not sinking this turn. Fix all also has crew morale effects that are discussed later. The most difficult damage to fix is that which was caused by combat. The rallying player may chose to reduce the ships damage total by 1 or 2 in one of the two areas by rolling 2 or 3 - 6's. Consequently, ships can conceivable repair all of the damage to their ship if given long enough to make rally rolls.

Crews can be forced to break off from action or strike, by bad dice rolls. A rally result of fix all, can rally a crew bad up. Such a rally can not be made while the ship is still under fire or being pursued. If a ship does rally back, and is forced to strike or break off a second time then they can not rally again.

Once a ship has scored a sinking result on a hull damage roll, it will sink that turn, unless a rally roll is made. If a crew can not rally (see the crew allocation section), then the ship sinks. If the crew can make a rally roll, then the player chooses how many of the 12 dice he wants to roll. This is a calculated risk that he can not afford to lose so 12 dice is what is normally rolled. If the rally results in fix all or damage reduced, then the ship remains afloat for another turn. On the next turn another rally will be needed to keep it floating again. If a sinking ship can reduce its hull damage to zero, then it is saved!

Damage control can also cause some problems.

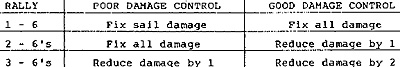

| Rally | Poor Damage Control | Good Damage Control |

|---|---|---|

| 1 - 1 | No Negative Effect | No Negative Effect |

| 2 - 1s | One Damage to Crew | No Negative Effect |

| 3 - 1s | Strike or Break Off | One Damage to Crew |

When damage control goes wrong men lose their heads. Some dive overboard, some run bellow decks, some just stop functioning. Whatever the action, the effect is that it depletes the crew and causes a hit. Another problem that can happen is that the men decide that the ship is too damaged to continue the fight. If they are in a fire fight or melee with an enemy ship then the ship strikes. If the ship is not being fought then it breaks off and sails back to port. Naturally, large military ships are not vulnerable to this problem.

CREW ALLOCATION

This is an optional rule, but one which I think makes a lot of sense.

Ships in the age of sail, were manned by relatively small crews. HMS Victory, for example, had only 800 men on board. To reflect that ships could never do everything at once, HMS Rules allow players to make only 1 calculated risk a turn. The player has to chose if he wants to sail, combat, or rally. This is often of critical importance! Some bad results will force players to make certain decisions regardless. This reflects the needs of order maintenance in running a ship. Sometimes one has to fix the car before it will drive.

The player may reallocate his crew every turn. Damage rolls are not part of this rule since no one wants to make them. Also if a player chooses combat as his calc risk then this allows him to both shoot his guns and fight a melee in the same turn.

SHIP CHARACTERISTICS

SHIP CHARACTERISTICS

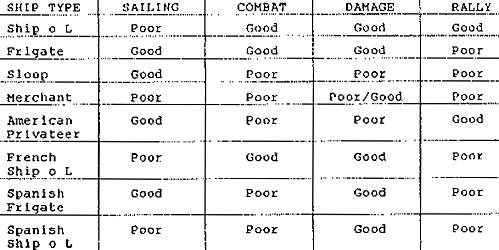

The following table lists some suggestions on what different ship's characteristics should be. I feel this is open to all manner of modification, as you see put.

These estimate are whole based on my biases. By my reading, British and American frigates were very tough (sometimes as tough as SOL). Frigates lack staying power though, so I give them poor damage control. American privateers were not noted for their great fighting qualities but they could sail like not tomorrow. They also had disciplined damage control. Spanish and French SOL are cut down from the British model. I rate Spanish frigates higher than Spanish SOL since I've read a lot about the Spanish Garde Costa in the Caribbean being very tough. Other ship types can certainly be added. Slave ships running the British anti slave blockade off West Africa, Chinese junks, Arab Dhows, what ever you want. The rules should work the same.

Back to Experimental Games Group # 25 Table of Contents

Back to Experimental Games Group List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 by Chris Engle

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com