These look like a fun set of rules to play. I am certain

they would be even more appealing if Steve Dake painted the

miniatures, since he does beautiful work. And they are obviously

simple. Do they have anything to do with the Indian Mutiny? I'm

not certain, but I'm also not certain that that matters ...

These look like a fun set of rules to play. I am certain

they would be even more appealing if Steve Dake painted the

miniatures, since he does beautiful work. And they are obviously

simple. Do they have anything to do with the Indian Mutiny? I'm

not certain, but I'm also not certain that that matters ...

Steve starts off his article by describing the process he went through to create a convention game. This process record is actually more interesting than the set of rules (which are as Steve admits stolen from everywhere).

The project arose due to the presence of a body of painted little men crying out to be used. This is where many projects begin. It seems likely that a lot of us buy miniatures without any particular game in mind. They often go unpainted for years in a closet somewhere. Then when reviewing ideas of what game to do next, we look at what we already have and are inspired by some figures that would be just right for a Crimean War game. If they are painted, great, but one seldom has all the figures needed for a project ready so some painting or borrowing inevitably happens.

Steve, like many miniature hobbyists, put most of his energy into the physical presentation of the game. Eventually though rules needed to be gotten. "Devil's Wind" and Steve's modified successor, fit in with the many "Sword and the Flame" types of games. These games seem to fit into the style of gaming pushed forward by Donald Featherstone. They clearly have no "objective" research to show that they are historically accurate. Instead they rely on movie imagery of what a given event should "feel" like. Fast action, thrilling chases, and dangerous melees are the stuff of movies. That fits in well with Steve's wonderful figures but is that why he chose this type of game?

The game had to be "easy to learn", not be "too bloody", "to reflect the desperate, fast moving, danger-from-every-corner type of action one expects from city fighting", and lastly let "the Brits ... have a bit of an advantage so that the battle would flow from one end of the table to the other." The game had to reach a conclusion in 3 to 5 hours, and be easily learnable in one or two turns by a novice. These are tall orders from a game.

Steve talks of looking at only one set of rules, but this leaves unsaid a number of decisions he made (possibly without even being aware of it). He opted away from any board game format. This is a natural choice, coming from a miniatures gamer. He also opted away from a role play approach and free kreigspiel. These are both very referee Intensive and are probably good approaches to avoid if one is ready to "machine-gun them all on the spot with a smile on my face." MGs also got rules out, though I can't imagine why.

Steve was left with the option of using a very detailed set of rules (I imagine that any detailed set of ACW rules could be :modified to do the mutiny) or more simple rules. Complex rules already violate some of the prerequisites of the convention game: 1. reach a conclusion in 5 hours, 2. be learnable in one or two turns of play, and be 3. fast moving. So there he is, firmly in Featherstone territory. If his requirements had been slightly different like say, be historically accurate and detailed, TSATF type games would be out.

Rules as we all know are every where. one can't swing a dead cat at a game convention and not hit fewer than two rules writers. Articulate rules writers, on the other hand are harder to find. Hobby journals, though, are full of simple rules sets that can work. Steve picked one and analyzed it, much as I do in EGG. It looked good on the surface. But all this means is that it is adequately logical, and easy to read. As Steve found out this is not always a good test of a game.

I've run games at conventions that I have not adequately play test. Sometimes they work, but more often they fail. Logic is no substitute for experimentation. Aristotle thought it was logical that heavy objects fall faster than light ones, unfortunately he was wrong. On playing the game, Steve found that "Devil's Wind" was wrong as well. He wanted a game that would give the players a "desperate" feel and not be "too bloody." By playing the game, Steve found that units were destroyed by fire in one or two turns. These kind of casualties lead one to despair not desperation. They also do not give players a chance to have the one or two turns to learn the game. Surgery was definitely called for.

Steve appears to have a few assumptions about the way casualties should work. For instance, a unit should not inflict more casualties in one turn of fire than it has figures! This fits the recognizable pattern of musket fire. It is not that accurate.

Now if this were a 20th century game, the assumption would be different. Machine-guns being what they are. There is also a recognizable pattern in melee. Melee is adjusted due to certain tactical factors like defending walls, and attacking in the flank. Steve kept it simple so that the players could spend most of their time moving little men around rather than consulting the rules.

What is of more interest to me is how Steve handled morale. A units morale starts at 20. It decreases by 1 for every figure lost in an infantry unit (or by 2 with cavalry). Morale is checked every time a casualty is taken. A 20 sided die is rolled. If the roll is less than or equal to the morale factor then the unit passes morale. If morale is failed, the unit retreats back 10 inches and AUTOMATICALLY RALLIES. This will cause fights in which positions are rushed repeatedly, followed by a repulse and a lull. I like this! It is though repeated tries and near misses that desperation is created. As the fight goes on units become less and less reliable to stand and fight, but rather than run off the board, they must be herded. (Another pattern I believe is a factor in war, often missed by game rules).

Units rout only on the roll of 20 on a 20 sided die. It does not matter if a unit has taken 50% casualties or none at all. So breaking become truly unpredictable. British units get to rally the first turn after a rout, which reflects their higher standard of morale and discipline. This also gives them that slight advantage that Steve wanted to balance the game in their favor. As Pandie morale drops, newly rallied Brit units can try again to push them out of yet another position.

All in all, Steve's rules look like they meet all his game prerequisites. So I'm not surprised that he got good reviews from the gamers at the convention. He knew what he wanted in the event and scripted it out in the way the rules worked. Nice job.

HOW COULD A MG BE ADDED TO THIS?

"The Devil Breaks Wind" is a simple set of rules that could easily incorporate a Matrix Game.

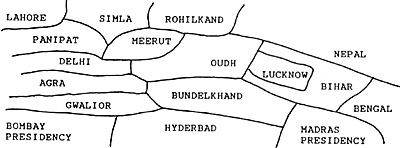

Say one wanted to run a mutiny campaign game. TDBW looks too simple to serve in this way but that is not true. The campaign area of the mutiny was really quite limited. It could be gamed out on the following area map...

The game could start off as a political game in which the Indian players try to start the mutiny, and see how many different units could be pulled into it. or the game could start as the mutiny begins. Individual colonels could try to keep their units loyal by riding into them and making a matrix argument. But the price of failing is death. The Indians could try to swarm the various isolated. British units, until reinforcements come up from Lahore, Nepal, Bengal, Madras, and Bombay. Hyderbad was ruled by the Nizam, who was already Independent and so remained neutral in this affair.

Defenders could hold up in Lucknow. Stemming they tide of revolt from spreading to Bengal. These actions could all be handled by using either the campaign or the Political matrix (or better yet by combining the two. If the players so chose, they would not have to use a matrix deck at all. Just write down arguments using the matrix format (ACTION, RESULT, THREE REASONS) and resolve the turn as normal.

Most campaign rules try to give guide lines for the effects of the rigors of the campaign on the troops. Such rules are always complicated and involve lots of book keeping. Forget them. If a negative event occurs in the campaign, let the players make arguments on how the combat rules should be changed to reflect the new situation. Say that the Indians find a strong central leader to unify their action. This might lead to their being able to try rallying after rolling a rout. Or maybe an argument to improve the works at Lucknow might result in that forts melee adjustment to be higher to reflect the Improved position. Desertion, battle loses, and disease, could cause units to start out battles with less than their 20 figure compliment (an so be weaker in morale).

Their is no need to have exhaustive rules to tell how to resolve every problem that can arise in a campaign. That is impossible to do anyway, and always limits players choice of actions. A Matrix Game does all of this with out all the work.

The fact that TDBW is a simple set of rules actually makes them better for a MG monitored campaign, since they are easier to modify in matrix arguments. Generals can keep focused on the business of campaigning, i.e. fishing for advantages over the other side while trying to reach the objectives, rather than futzing around with book keeping.

This could be a fund campaign game to run in a local club. It could generate a lot of exciting battles, and give a good excuse to give the little men a work out! Try it out!

Back to Experimental Games Group # 21 Table of Contents

Back to Experimental Games Group List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 by Chris Engle

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com