EGG is a forum for new game ideas. It is also a place to play a

yearly PBM. This coming year the game will be a Matrix Game of Arthur

Wellesley's 1808 campaign in Spain. It promises to be fun for all who

play or follow it.

EGG is a forum for new game ideas. It is also a place to play a

yearly PBM. This coming year the game will be a Matrix Game of Arthur

Wellesley's 1808 campaign in Spain. It promises to be fun for all who

play or follow it.

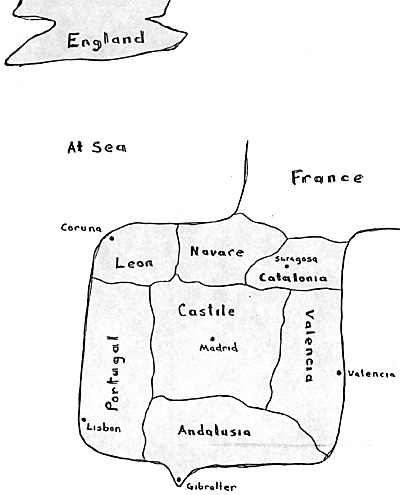

The Peninsula Campaign is of particular interest ot historical wargamers. Why is this so? For one, the battlefields of Spain are the proving ground of the Duke of Wellington. Goya added to this with his pictures depicting the French Invasion, which remain some of the most potent images of war ever. And then there Is that word "Guerrilla." 1808-13 is indeed a period with depth. My hope is that an MG will be able to do it justice.

French Forces:

- France - 1 large army, Napoleon

Madrid - 1 small army, Murat

Lisbon - 1 small army, Junot

British Forces

- At Sea - 1 small army Wellesley

Andalusia - 1 guerrilla, El Incognito

Leon - 1 guerrilla

Valencia - 1 guerrilla

Saragosa - 1 guerrilla

THE MATRIX

Actions

1. Normal March

2. Forced March

3. Rest/Prepare

4. Rally

5. Ambush

6. Skirmish

7. Open Battle

Results

1. Victory/Defeat

2. Morale Increases/Drops

3. Fatigued

4. Halt

5. Retreat

6. Rout

7. Recruit/Desert

Reasons

1. Tactical Advantage

2. Terrain Effect

3. Large Formation

4. Small Formation

5. Weather Effect

6. Supply Lines

7. Motivation

8. Battle Cry

9. Anger

10. Fear

11. Shame

12. Love

3 Wild Cards that can be any element that "should" be in the matrix.

CAN A MATRIX GAME RUN A CAMPAIGN?

One application for MGs is to run miniatures campaigns. It sounds like a good idea, but do they work? The answer lies first in how normal campaign games work...

1. The referee asks the players for a set of orders about what their troops are going to do. The orders are usually written. They spell out in fair detail what the general wants to do. When the plans of the two opposing sides conflict, the issue is either settled by a miniatures battle or a die roll. If it is settled by a die roll then the two sets of orders start looking a lot like matrix arguments in which only one side wins.

It would seem then that yes, MGs can work to run campaigns since in effect they are nearly being used now. There is one big difference though. MGs require that the player be much more conscious about the fact that he is "making up" what he wants, to happen next. This can range from the traditional ("My army marches to Lisbon.") to the weird ("Disease breaks out in the enemy camp. To the unheard of ("The enemy garrison surrenders out of fear of me.").

The net effect of all these "creative" arguments is that what happens next in the campaign is impossible to fully predict. Like a game of Diplomacy, it depends on who is playing. Still there are clear winners and losers, and decisive reasons why to fight.

Those who have played MGs before will notice that this games matrix seems extremely short. It is. This matrix is intended to be a generic matrix to run any type of campaign up to the colonial wars of the late 19th century. More than any other matrix, this one is meant to "suggest" possibilities to the players rather than tell them what to do. The section of rules will explain more fully how this works.

Finally, it is clear that MGS work to run campaigns because I've run them. Chris Morris, and Howard Whitehouse are even now movng their armies closer to Khartoom in a Sudan MG. I've also used the above matrix to make decisions for commanders in solo wargames. It works great and creates a solo game that is exciting and unpredictable despite the fact that I make all the arguments. I hope that you will be able to join into this game.

THE RULES

What follows are the basic rules of Matrix Games. They are meant to be a short reminder to those who are already familiar with the system. If you are new to this type of game you might find it helpful to get a copy of "Swashbuckler: A beginners Matrix Game." Just send me a letter with info on how to get a copy to you.

Matrix Games consist of players making arguments about what they want to happen next. Each argument consists of an ACTION, a RESULT, and three REASONS why it should happen that way. This is simple. What is difficult is deciding what to do every turn. The problem comes from being free to chose ANY action. In such a case how does one know which action Is the "best?"

As generals have discovered throughout the ages, simple plans work. On the campaign level this means marching toward the enemy on the most direct route and attacking him. If possible, cut his supply lines. Beyond this there is little more to know. it is useful to cause desertion in an army that is already losing, or disease in any army, but this tends to be an act of desperation (kind of like the Japanese planning for the Mongols to be destroyed by a divine wind).

Examples of arguments ...

ACTION:

Element: Normal March

Spoken: Napoleon orders his army to march on Madrid at a

normal pace.

RESULT:

ditto: The army starts moving and will stop when it reaches

Madrid.

REASON

1. Motivation: Napoleon Is with them!

2. Battle Cry: Liberty, Fraternity, Equality!

3. Fear: They fear punishment for not obeying a direct order.

ACTION

Element: Skirmish:

Spoken: The Guerrillas skirmish with Napoleon's army.

RESULT

Supply Lines: Napoleon's supply lines are cut.

REASON

1. Tactical Advantage: The Guerrillas are everywhere.

2. Small Formation: Small units can evade big units.

3. Terrain Effect: The mountains are good cover.

ACTION:

Element: Supply Lines

Spoken: The Guerrillas keep the supply lines cut.

RESULT

Morale Drops: The morale of Napoleon's army drops one level

until resupplied.

REASON

1. Terrain Effect: Guerrillas work well in mountains.

2. Shame: It is a disgrace to be invaded.

3. Wild Card: El Incognito is related to ALL the local

families who greatly aid him.

All arguments are built up from elements from the matrix. But as one can see, a spoken argument is also included to explain and elaborate on what the element means. The matrix elements tend to be broad catagories that suggest many meanings so the spoken argument is very important. The wild cards in particular depend on the spoken argument to show how they fit in.

Every player gets to make ONE argument a turn that must be designated to be related to 1. an army, or 2. a city or area.

To keep this game simple, there will be no "counterarguments" in this set of rules. Every argument is considered to be equal to any other argument unless the player has used past argument to set up this event. In this case the referee (me) may rule that it is a strong argument. I may also rule an argument weak if it lacks sufficient precursors.

Argument resolution is done thus: roll a six sided die for every argument. If the argument is neither strung or weak It succeeds on a roll of 3 or less. If it is strong the roll Is 4 or less. If it is weak, 2 or less. Generally one roll decides wither an argument happens or not. If there are two or more arguments about the same army or area the one WILL happen. The die rolling is done as above but it is kept up until only one argument is NOT ruled out. As rolls are failed, and arguments are ruled out, the losers drop out of future rounds of rolls. If all the arguments are ruled out, then start a new round of rolling with all the arguments back in the running. (This can be a very exciting process to go through. Especially when three or more arguments go into their second or third round of rolling.)

The results of winning arguments become what happens that turn. Results might include, causing armies to move, forcing a battle to happen, or something nasty (like disease in camp). If the result is that a battle happens then the players can fight out a miniatures battle using whatever rules they like.

Once a turn is over the next turn can begin. This keeps up until one side's commanders decide that they want to quite. This usually happens to the side that never wins an argument and loses every battle they fight. Historically of course this is what happened to France (despite the fact that the Spanish were "not good fighters.") Who knows who will win the war this time?

PENINSULA CAMPAIGN RULES

PENINSULA CAMPAIGN RULES

This PBM is meant to cover the event from August to December 1808. As the history buffs will realise this is from the moment that Wellesley landed in Portugal until Napoleon recaptured Madrid.

Each Turn represents one month of time. At a normal march an army may move from one area to all adjacent one in a single turn. An army may move two areas a turn at a forced march if the areas are unoccupied. (Note: the sea area between England and the continent is always unoccupied, since the French lost their fleet in 1805.)

Armies of opposing sides may be in the same area together. A battle only occurs between them when an argument says one happens. Only one side though can be in control of a city that is in the area. Supply lines must be drawn to either France (for the French) or a port (for the British). Only the Spanish are able to pull enough supplies out of the local peasants to survive. A supply line can be drawn through at, enemy controlled area, but it is unlikely that they will not argue to cut it as soon as possible.

When a battle, skirmish or ambush takes place I will fight them at the local club using whatever rules strike my fancy. Battle happen only when arguments say they happen. If you are interested in fighting out a battle yourself, please do. I will have to go with the locally produce battle results for the game but since the purpose of a campaign is togenerate battle scenarios there is no reason why they can not be gamed by several people. I only ask that you let the rest of us know how it comes out. The losers a battle must retreat all remaining forces to an adjacent friendly area--referee's choice.

The game uses only two types of units, small armies (10,000 to 30,000 men) and large armies (around 100,000 men). Just to keep it simple, one large army equals four small armies. Newly recruited forces are small armies. Desertion can cause a small army to disintegrate (but obviously this is not a strong argument for French or British units who are alone in a foreign land). It is likely that supply problems, disease and desertion will be critical in this campaign. Some results give unit status like "fatigued" or "out of supply." These status stays with a unit until an argument or some action removes them. They can be used against an army in future arguments, and I will take them into account when deciding on the strength or weakness of an argument.

AFTERWARD

The Peninsula Campaign will be run until 1992. If you are interested in playing, decide which side you want to win and then send in some orders. I believe it helps to chose a general who you want to win, and sort of role play his career with your arguments. Keep in mind though that you can make arguments for any army or area on the board.

ALL ORDERS WELCOME! REMEMBER THOUGH, ONLY SEND IN ONE ORDER A TURN AND THERE ARE NO COUNTER ARGUMENTS IN THIS GAME.

Back to Experimental Games Group # 12 Table of Contents

Back to Experimental Games Group List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1991 by Chris Engle

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com