This article is concerned with French practice in forming tactical columns with a frontage of two companies. It may be helpful to preface it with the following table of terminological equivalences.

| Administrative Units | Tactical Units | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| French Nap. | Translation | English Nap. | |

| 1/2 company | la section | section | sub division |

| (English) company | le peloton | platoon | division (maneuver) |

| (French) compagnie | le peloton | platoon | platoon (firing) |

| 2 companies | la division | division | grand division |

I will adhere to the convention due, I believe, to Becke, of denominating a Division (several brigades) with a capital and a division (2 companies) with a miniscule. I will use the English translations, not the British Napoleonic terms. Subdivision will be used to mean a section, a platoon, or a division indiscriminantly. The distinction between administrative and tactical units, while critical and interesting, must be left in its details for some other article. Here only the tactical terminology will be of real concern.

The reader of Napoleonic military history should always be very careful in reading the word "column". It has a wide variety of different meanings. It can mean a strategic or tactical grouping of anything from a single company to an army, under some specific commander and having some particular assignment to carry out. It can mean a tactical or route formation of any of several varieties. Some tactical columns are actually used as route columns, while other route columns consist of nothing more than a unit in line but marching to the flank. Some route columns are intermediate in nature between the two possibilities.

In the case of both tactical and route columns anything may be involved from a single unit to an army. Naturally provisions carried out and arrangements made differ with the size of the force involved. They also differ with the army involved, whether infantry, cavalry, or artillery. Finally, the term column is often applied loosely or even sarcastically to certain other tactical situations.

For example, a line of battalions in which there has been a general drift to the rear of individuals or entire battalions in the course of a lengthy firefight is often called a column. This was the nature of the so-called column at Fontenoy. Similarly, a body of cavalry in line which has become strung out over a considerable depth as a result of a long advance or disorganization is also called a column at times by courtesy.

This article will be concerned mostly with a certain type of tactical column. In describing tactical columns there are three parameters of interest. First, there is width. A column may have the width of a section, a platoon, or a division. Only the latter two possibilities will be considered here. Columns of sections were mostly used by the French for route columns or for passing through constrictions, in cross-country marching (i.e., for passing defiles).

Column organization is based on that of line formation, from which it is secondarily derived. In essence, each platoon is always in line. In line the platoons in their little line formation are arranged "in line abreast" (to borrow from naval terminology), while in column they are one behind another "in line ahead". Thus, even in a column formation, a file of two to four men is more concerned with the location of its neighboring files to either side than with the file in front of it or behind it in the adjacent platoons. In short, a column is not a phalanx in which the basic subunit is a file as deep as the whole formation, but a piecewise disassembled line in which the platoons (pieces of the original line) are the basic subunits.

This is the essential difference between the formations of the 18th through the 19th Centuries and those of the 17th Century that had preceded them, or between the formations of the Guibert and related Regulations for infantry and those of the hard-line partisans of the "ordre profond", like Mesnil-Durand or Follard.

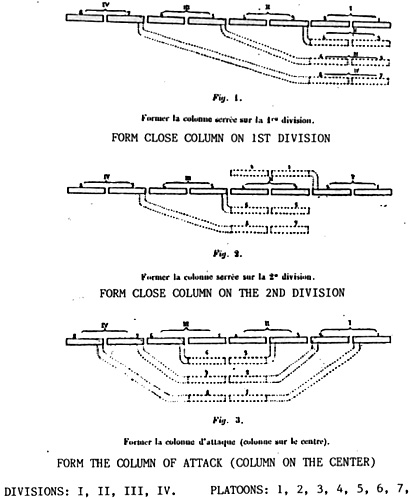

FORM THE COLUMN OF ATTACK (COLUMN ON THE CENTER)

FORM THE COLUMN OF ATTACK (COLUMN ON THE CENTER)

DIVISIONS: I, II, III, IV. PLATOONS: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8.

THESE FIGURES, REPRESENTING FORMING OF CLOSE COLUMNS FROM LINE

WITH A PRE-1808 8 COMPANY BATTALIONS (MINUS THE GRENADIERS) ARE TAKEN

FORM COLIN'S "LA TACTIQUE", P.XXX. THE DIAGRAMS ARE ALSO RELEVANT TO

DEPLOYMENT INTO LINE FROM THE INDICATED COLUMNS.

Distance

The second organizational parameter is the extent of distance between succeeding subdivisions (platoons or divisions) in the column. The French Reglement of 1791 recognized a variety of distances. Closed columns had the succeeding subdivisions within a meter or so. These columns were known as "colonnes serrees" or "colonnes en masse". A reader should carefully consider whether an author referring to "massed columns" is referring to several closed up columns at appreciable distances from each other, to a single unclosed column composed of several battalions, to a number of battalions operating close together in any formation at all, or to nothing at all: that is, using the term simply because all French battalions are automatically "in massed (or heavy) columns" to that author.

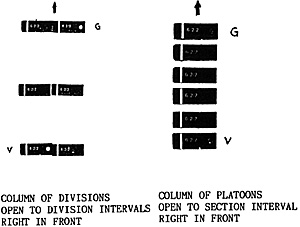

Columns that were not closed up were termed opened "to such-and- such a degree". Open columns were permitted distances or degrees of opening of a section's width, a platoon's width, or a division's width. The maximum degree of opening for a column was the width of the subdivisions comprising the column. (Columns of platoons at divisional intervals were not used, for example.) The French form of the terminology for an open column is "colonne a distance de section, peloton, division". When a column was at its maximum degree of openness, it was termed "colonne a distance entiere".

Arrangement

Arrangement

The third parameter is the most interesting. It refers to the pattern of arrangement of the subdivisions in the column. Three arrangements were used by the French: right-in-front (sur la droite), left in-front (sur la gauche), and on-the-middle (sur le centre). The latter case is particularly well provided with alternate terminology, so the reader should be prepared for such forms as "central columns", even within this article!

To understand all of these terms, the reader must visualize the battalion first in line. The grenadier platoon is on the right; leftwards from this proceed the fusilier platoons in numerical order, culminating in the voltigeur platoon on the far left. Since there Were an even number of platoons (in the 6 company battalion of 1803 on), the platoons could be grouped into divisions two-by-two proceeding from one flank to the other. With 6 platoons, there were, of course, 3 divisions, termed the divisions of the right, the center, and the left.

In a column on the right, the right-most division or platoon was at the front of the column, and the other divisions or platoons followed it in order from front to back as they lay in line to its leftward. The exact reverse was true in a column on the left. In a column on the center, as it might be deduced, the middle platoons of the line were at the front. This produces the result that less value, in the case of a line (here, a multi-battalion column or echelon) of battalions, because, for example, in the case of a deployment on the right of the whole (that is, on the first division of the first battalion of a column right in front), the battalions receive the protection successively of each other's fire (as they come up to deploy on the left of the battalion(s) already deployed).

"(Pelet:) However, even if I admit the column on the middle neither as the basis for a deployed order (battalions acting alone or widely separated) or for the maneuvers of an entire Division (acting in one or more large columns), I recognize that this formation (column on the middle) has a great many useful properties; without speaking of its deployments or its internal rearrangements, it offers extreme ease of formation of squares while marching, and of separating the battalion into two halves for attacks on both flanks (of a small enemy position).

It is possible to deploy to the right or left into line, to resume the column (from this line) to the flank (original direction) (reprendre l'ordre direct), either to the fore, by undoubling the platoons on the left, or to the rear, by means of cycling the platoons to face them rearward in the column and making a countermarch. (This sentence is unclear to me, and seems to merely sketch some fairly complex maneuvers.) The extreme simplicity of the column on the flank (right or left) should make it the preferred form; but, for a small number of battalions, or for a regiment, there is a good deal of advantage to be derived from the column on the middle.

"(Pelet:) Seduced by the idea of having a single (type of) column with the advantages which a column on the middle provides, I did in the past adopt it as the basis for a concise set of maneuvers. Such columns resemble greatly the French Order which Mesnil-Durand (a proponent of the "shock" school) proposed, and which he extended in principle to entities on the largest scale (e.g., brigade columns in which the central battalions form the front), and with the unsatis- factory results seen at the Vaussieux Maneuvers. Columns on the middle have also been proposed by General Meunier in his Dissertation sur Vordonnance de Vinfanterie (1805) (Dissertation on the Infantry Regulations), but they seem to have been abandoned by him in his Evolutions par brigades (1814). (Colin notes that these were the dates of actual publication; both works were circulated in the manu- script before this.)

Reflection has sufficed to make me now prefer columns on this flank, in which the platoons have their usual numer- ical order. These have the great advantage of being able to double and undouble their divisions, platoons, and sections almost infin- itely. (That is, a column of divisions on the right converts to one of platoons on the right by having the left platoon in each division insert itself into the interval behind the right platoon. This is an example of "undoubling".) Also, columns on the flank (of several battalions one behind another in the same kind of column on the flank) may deploy successively and immediately, because each platoon is adjacent in the column to its future neighbor in the line.

"(Colin:) Moreover, circumstances generally militated against the formation of columns on the middle in a combat situation, as indicated by Chambray in De l'infanterie:

"(Chambray:) The column of attack is not employed as often as one would believe, and here is the reason: infantry, when it is following a road, and when it is at a safe distance from the enemy, ordinarily marches by the flank. (That is, in a route column of three's, formed by having the men in line face right or left where they stood). When the enemy is close enough to make it necessary to get ready to assume position, the column leaves the road and forms itself by platoons. (It steps off the road to its flank, closes up the sloppy intervals of the marching column so that the line is reformed, tells off into platoons if it is not already so, and wheels these platoons 90 degrees into a column of platoons on the flank, fully open.) Then the column doubles its platoons to form a column of divisions (still on the flank), closes up to intervals of a section's width, and is then ready to shoulder arms and assume an accelerated pace, if that is necessary... (Colin's diaresis).

One can see that to form a column on the middle, it would be necessary first to deploy (from the column of divisions on the flank into line, following this be deploying from line into a column of divisions on the middle.)"

I feel that the words of Pelet, Chambray, and Colin above show that columns of attack (columns on the middle) saw little or no use by the French, at least from 1805, on a basis of both theoretical considerations and practical ones, and that this was especially the case in multi-battalion columns of Divisions or brigades as a whole, and in rapidly developing fights.

It does appear that the Eastern European powers (Prussia, Austria, Russia) made more extensive use of columns on the middle. This may have been the result of borrowing documented, but obsolete French practice. It may also have been the result merely of a theoretical preference. Jomini, whose writings were influential with both the Austrians and the Russians, was a partisan of the column on the middle.

It might well be asked at this point what uses the variety of columns possible were put to. If we ignore columns of divisions on the center, this leaves columns of platoons or divisions on the flank. It has already been shown that the former might arise transiently in the process of forming a column of divisions from a route column or might be adopted by battalions with less than 6 platoons present. otherwise, columns of divisions were the theoretical preference. The more closed up a column was, the easier it was to keep it in order while leading it straight forward.

To turn with any facility, a column had to be somewhat open. This permitted the subdivisions to gradually adjust their heading, or to wheel while succeding subdivisions came up to the point of wheeling, instead of making these wait. A column had to be somewhat open to form square quickly. Closed battalions deployed from the halt, while open battalions could deploy on the march, by altering the headings of the platoons.

Fully open columns could wheel their subdivisions 90 degrees on one flank to form the battalion into line to the flank. This was a very simple and easy maneuver for a column of platoons, and was the basis of Frederick the Great's famous flank attacks. A wheel of two columns of platoons composed of a brigade and a half each into two lines, one behind another, performed by the Anglo- Portugese Division of Packenham at Salamanca commenced the successful attack on the deploying French Army of Portugal there.

At Albuera, the French Division of Girard advanced with two battalions in open columns of platoons on its left, outer flank. When the British brigades attacked that flank, these battalions wheeled into line at right angles to the axis of advance of the Division, and blunted the British attack, which was then annihilated by a flank attack by a regiment each of French and Polish cavalry.

It should be noted that a column right in front can only deploy to the left by the wheeling maneuver; conversely, a column left in front can only wheel into line to the right. Wheeling the other direction has the effect of reversing the order of the platoons over what is permitted. Very few officers were willing to submit their men to the confusion that might result from this reversal!

This article may be of assistance to miniatures wargamers wishing to gain an appreciation of the variety of columns subsumed within the single column formation of many rules systems. I hope that it will to some extent have suggested what forms of columns were used in what situations, and why.

A start in the direction of introducing varieties of columns was made by Mike Scholl in EEL Nbr. 42, when he suggested that a distinction might be made between open and closed columns with respect to their shock ratings, firepower vulnerability, flexibility, etc. It will be obvious that I would be inclined to disapprove of making the distinction in terms of bonuses for shock attacks. I strongly encourage differences of other sorts, though, primarily in terms of movement rates reflecting slowness brought on by difficulties in retaining order, in terms of maneuvering restrictions affecting turning and formation changes, and in terms of firepower vulnerability.

Mr. Scholl suggests representing open columns by reversing the facing of the last subdivision of the column. I would recommend instead that the stands be placed at distances of a stand width or less as appropriate. Probably some difficulties will occur here for reasons of stand depth, though. I am afraid that I must admit at this point that I wouldn't know, since I'm a boardgamer, and what previous thought I've applied to the matter has been mostly devoted to how to represent these things in situations where the whole battalion is represented by a single cardboard counter! That approach has advantages and disadvantages.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jean Colin. L'infanterie au XVIIIe siecle - la

tactique. Berger-Levrault, Paris, 1907

Jean Colin. La tactique et la discipline dans les armees de la

Revolution - Correspondance du general Schauenbourg. Chapelot,

Paris, 19U2,

- These two works are extremely important secondary sources for the

student of French Napoleonic tactics. They are the principal sources

for Quimby's Background of Napoleonic Warfare, widely available in US

Libraries.

Correspondance de Napoleon Ier. Plon, Paris, 1869

Jomini. The Art of War. Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1875

Kriegsgeschichtlirlie Abteilung II, Grosser Generalstab.

Das preussische Heer der Befreiungskriege - Das preussiscbe-

ffeer im Jahre 1812. Mittler, Berlin, 1912

H.C.B. Rogers. Napoleon's Army. Allen, Shepperton, Surrey, 1974.

- Contains a translation of portions of the Decree of the 18th

of February 1808, relevant to tactics with the 6 company

battalion.

Where the source of a figure is not indicated, it is a reduced photocopy of a figure constructed on a photocopying machine with GDW's System 7 (Copyright) counters for Napoleonic miniatures style wargaming. With appropriate modifications, these can be used with any set of miniatures rules. (Scale as for 7mm. figures.) GDW also publishes a special set of their regular Fire & Steel rules for use with System 7.

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 1 No. 86

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1985 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com