This installment, as promised, will look at the battle of Austerlitz. Let's look back for a moment and see how we got here. I suggested in a past column (and in THE COURIER Vol. V No. 6) that an examination of Napoleon's battles (and those battles are what attracted us to this era) would show that each had an overall structure of attacker/defender instead of the normal wargamer set-up of an encounter battle or mutual attack. (I note that in EE&L 82 Mike Gilbert calls on readers to investigate the occurence of such encounter battles for the era.)

This does not mean there was an absolutely rigid adherence to a particular role, but suggests we look at data with a different frame of mind to see if that would change our definitions of what we expect a battle to be like. If so, it would also mean changing our methods of wargame simulation.

If such an hypothesis is true, we should test it first against Austerlitz, a battle (as discussed last time) that seems to be the classic wargamer's mutual attack/encounter battle. Indeed, 1 used Doctor Christopher Duffy's excellent work AUSTERLITZ 1805, as a basic source of information, and he states that the failure of Weyrother's plan occured for "the fundamental reason ...that their army was not up to the tactical outflanking move which had been demanded of it." (pg 157) Most wargamers who simulate Austerlitz as a mutual attack battle also rely on Duffy. How can the same well-researched source convince some readers that Austerlitz was an example of mutual attack and others (well, at least me!) that it wasn't?

That brings us to one last point also mentioned in past columns, that past WARGAME experience influences interpretation of what one reads. The wargamer puts limits on the battle by the four table edges. Within that area we give territory to each sides, examine where the forces of one collide with the other; the history we read is then interpreted to fit our limitations instead of a broader context an historian might have. Thus many might interpret the failure of Weyrother's plan to mean that given a mutual attack situation on a fixed battle area one side's troops were unable to carry out their attack through an "outflanking move" (which must occur near the edge of the table or entering on to the table) before the other side could get his attack in. Their simulations therefore reflect their previous prejudice, which is to have both armies moving at each other, colliding all over the front and leading to a fairly unplayble game.

Therefore I'll present an alternative interpretation of Austerlitz stressing it's psychological context. This in turn shows the typical wargamer's map as more accidental, and Austerlitz not as a wargamer's "battle", but as a surprise attack on what was almost the equivalent of a strategic march. My friend Richard Burnett of Pasadena, Cal., suggested a good term that gets the idea across - rather than a battle, Austerlitz was a strategic "ambush".

My sources are Duffy and A DETAILED ACCOUNT OF THE BATTLE OF AUSTERLITZ, by THE MAJOR-GENERAL STUTTERHEIM. (Translated into English from the French by Major Pine Coffin (!), in London in 1807). Duffy states "Fortunately the Austrian, General Stutterheim, lost no time in getting down to work, and within a couple of years his published account reached a wide European audience. The book is remarkably objective, considering that it was composed so soon after the event." Stutterheim participated in the battle as commander of part of the cavalry of Kienmayer's column.

In earlier WINTER QUARTERS columns I stressed the need to look at the strategic plan before looking at any one battle. Therefore let's see how Duffy describes it;

- The final decision to advance was taken on 24 November, in the mood of euphoria induced by the arrival of the Russian Imperial Guard. Not everyone could share in the jubilation. Sir Arthur Paget was aware that the Austrians at least had a few skilful commanders at their disposal, '-all good and experienced officers, but for the other when i reflect that he (Alexander) is to be provided by Kutuzov and Buxhowden ... and God knows who, then I own 1 tremblenobody knows exactly where the French are, or in what force'."

Now that the army was committed to the offensive, Weyrothe: explained the strategy in the following terms. The united force of 89,000 men was to be kept together in a block, 'and to begin with we shall attempt to win the enemy's right flank, and take up a position which will threaten his communications with Vienna, thereby forcing him to abandon Brunn without a fight and tetire behind the Thaya. If this ... movement does not produce the desired effect, we shall exploit the advantages of our own position and superior forces and launch a decisive attack against his right flank, which will drive him from his ground and throw him back on the Znaym road. Subsequently we shad send strong raiding detachments racing ahead from our left wing, and in concert with the corps of Archduke Ferdinand, who is advancing on Iglau, we shall compel the enemy to retreat through the track. less mountains above Krems.

A `disposition' for the move was hurriedly distributed among the generals. The army was supposed to move on 25 November, but the necessary provisions could not be collected before the 26th, and 'when that day came, some of the generals had not sufficiently studied their dispositions; and thus, another day was lost'.

Note that the Allies are committed to an offensive movement, without knowing the exact strength or location of the French. How could such a decision be taken with 'jubilation'? The tone of weyrother's explanation gives the clue - the Allies felt they had superior numbers, position and future potential. Ferdinand was advancing and the French were felt to be at the end of their rope. The fact that Generals had not studied their 'disposition' might be the result of more than just incompetence - it could also be that overconfidence and the belief that the French were no longer a threat led to carelessness. The Allies' own logistic problems were more pressing to the generals than the enemy was.

Weyrother's strategy here is interesting because it assumes victory through maneuvering around the French and forcing Napoleon to retreat. It implies that any French decision to stand and fight would be an unrealistic one, which would be easily defeated due to the Allies' strategic superiority. It is important to note that strategy was made on November 24, and lacked knowledge of enemy position or strength in other than general terms. The fact that this was basically the same plan carried out at the Battle of Austerlitz would seem to imply;

- a) the Allies had received no further indication of any change in the strategic situation; thus there was no need to change their plan nor their optimistic mood

on the day of Austerlitz, the movements taking place were still of a strategic marching nature; only if the 'movement does not produce the desired effect' would real battle take place. Thus, as the Allied columns were marching off the Pratzen, it was not with the idea of fighting a battle. Rather, it was with the intention of marching to a location at which a battle would be fought ONLY if the French were foolish enough to hang around and be beaten.

Duffy shows Napoleon reinforced the Allied attitude:

- Further clarification came from Napoleon's reliable aide General Savary, who had been sent to Olmutz for the ostensible purpose of replying to some peace feelers from the allies, but really to find out what these people were thinking, and to convey the impression that Napoleon was afraid of battle. Tsar Alexander had received Savary with the utmost courtesy, but charged him to carry back a letter addressing Napoleon in the insulting style of 'chief of the French government'. The bellicose manner of Alexander's glittering young entourage confirmed Savary in the conviction that the allies were looking for a fight.

Now began the extraordinarily risky game by which Napoleon invited the enemy to come at him by creating an appearance of weakness, while all the time he consolidated his positions and brought up his reserves to within reach. Too great a show of force would frighten the allies away and leave him as badly off as before, yet he could scarcely allow the enemy to pounce on him before he had gathered his army.

Stutterheim tells how this confirmed Weyrother's wisdom at Allied HQ;

- The allies flattered themselves that the enemy would not risk the fate of a battle in front of Brunn. After the 28th, this hope became the prevailing opinion at head quarters. Then, instead of hastening their movements, they wished to manoeuvre, at a period, when too much had been risked, to enable them to avoid a decisive action ; if, contrary to the opinion of those who thought the French would not fight, they still persisted in not retiring.

Napoleon was in control, as Duffy shows;

- The allies continued to re-shuffle their columns on 30 November. They were short of food, and they moved painfully over bad country tracks in complete ignorance of the whereabouts of the French, who were in fact little more than three miles away. still milling about in some confusion. Everything reinforced the impression that the enemy would ultimately advance over the Pratun with the intention of turning the French right.

Napoleon proclaimed to the marshals `I could certainly stop the Russians here, if I held on to this fine position; but that would be just an ordinary battle. I prefer to abandon the ground to them and draw back my right. If they then dare to descend from the heights to take me in my flank, they will surely be beaten without hope of recovery.

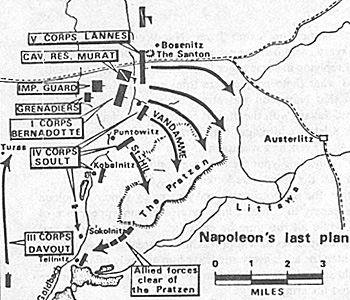

Once the enemy were fully committed in the Goldbach valley, Napoleon intended to fall on the flanks and rear of their salient. Approaching from the south-west, Davout with the III Corps would take the host in the left flank; more important still, the mass of the main army was to debouch from the Santon area to the north, and sweep over the Pratun plateau, which by now would have been abandoned by the allies.

The various impressions of the night strongly indicated that the allies were going to make their main effort even further south along the Goldbach than Napoleon had expected. He responded by formulating his 'Third Plan', a blanket term for the individual instructions which were issued in the early hours of the morning, and confirmed in the final orders group with the marshals just before the battle.

He knew that he had the power to choose the battlefield as well as which role, attacker or defender, to play, as long as Allies didn't know where he was. He could choose a position and 'stop the Russians here' in an 'ordinary battle' (implying that in an ordinary battle the defender only needs to stop the enemy attacker to 'win'), or to ambush the enemy while he marched (assuming he could continue to keep the Allies in the dark), or to attack the Allies when they were on the Pratzen in a 'defensive' role.

He knew that he had the power to choose the battlefield as well as which role, attacker or defender, to play, as long as Allies didn't know where he was. He could choose a position and 'stop the Russians here' in an 'ordinary battle' (implying that in an ordinary battle the defender only needs to stop the enemy attacker to 'win'), or to ambush the enemy while he marched (assuming he could continue to keep the Allies in the dark), or to attack the Allies when they were on the Pratzen in a 'defensive' role.

To become the attacker would only be feasible if the enemy descended from the Pratzen; something they might not do if they had full, accurate intelligence, or any change in their attitude since 24 November. Stutterheim points out the advantages of the Pratzen position for the Allies, and also the psychological reasons for not using it.

- offered the means of delay; and the very elevated points of these heights afforded strong means of defence. Here, as in the

position, in front of Olmutz, the army was posted on a curtain, behind which massive columns might be posted, ready to act offensively. Its left was secured by the lakes of Menitz and Aujest, while the right was refused. But the taking advantage of this position was never thought of, any more' than the possibility of being attacked on these heights, or of finding the enemy on this side the defile. The French emperor took advantage, in a masterly manner, of the faults that were committed.

Thus, Napoleon's victory at Austerlitz was not due to a momentary tactical advantage of having the Allies off the heights instead of an them, but to the strategic climate he created (or, at least, exploited) that made the Allies think they weren't on a battlefield, but on a march. This meant that when combat actually came, the French were the attackers, and the Allies had to become defenders on ground not of their own choosing, before they could deploy for battle. Naturally there is tactical advantage to having the Allies off the heights, but that was not the most important factor.

Napoleon was so successful that the night before the battle many of the Allies thought he was retreating, just as they assumed he would. Duffy points out;

- However, Prince Dolgoruky's one anxiety was that the Grande Armee might slip away before it came under attack. He betook himself to Colonel O'Rourke at the advance posts along the Goldbach, and told him to mark narrowly the direction of any retreat. On the far right the coming of darkness found Bagration's leading troops on the 6i11 to the south of Kowalowitz.

'Not far behind the entire army was in bivouacs. To our front we could see a few enemy fires, which seemed to indicate the line of their advanced pickets. Everything was silent in the direction of the hostile army, and we were nearly all convinced that the enemy were retreating. At about midnight fires suddenly blazed into life across the foot of the heights on which we were standing,* and we could we their bivouacs extending across a wide stretch of ground. Obviously the enemy were not bothering to conceal their retreat, or so it seemed to many of us. But some people had their doubts.

Many wargamers often assume that battlefield maps we see in books must reflect the way the battlefield appeared to the participants. They might assume that Austerlitz was 8 miles wide, with Soult covering half the French front while the rest of the Army massed behind the northern half. Furthermore, for the Allies 'to turn the flank' means to attack at either the north or south edge of the table, since that is how most games are played.

In 1805, however, the Allied army did not have the same perspective of the French positions. Stutterheim gives us that view and also shows that the Goldbach (a major feature in wargame Austerlitz plans) held little significance for Allied planners;

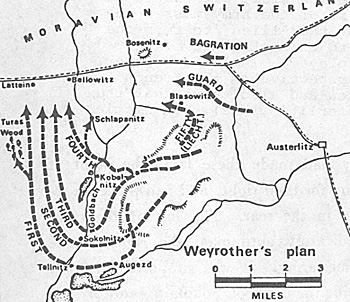

- It was supposed that the French army was weakening its centre to reinforce its left. Several lines of smoke, which had also been perceived the evening before, between Turas and the lakes in rear of Sokolnits, and Kobelnitz, and some others near Czer, nowitz, caused the belief that the French army had made these lakes the point of appuy for their right, and had placed a reserve in the rear. The left of the combined army outflanked the right of the French army. It was supposed, that by passing the defile of Sokolnitz, and of Kobelnitz, their right would be turned, and that the attack might afterwards be continued in the plain, between Schlapanitz and the wood of Turas, thus avoiding the defiles of Schlapanitz and Bellowitz, which, it was believed, covered the front of the enemy's position. The French army was then to be attacked by its right flank, upon which it was intended to move down large bodies of troops; this movement was to be executed with celerity and vigour; the valley between Tellnitz and Sokolnitz was to be passed with rapidity; the right of the allies (on which was the cavalry of Prince John de Liechtenstein, and the advanced corps under Prince Bagration) was to cover this movement. The f irst of these generals on the plain between Krug and Schlapanitz, on each side of the causeway; and the other by protecting the cavalry, and occupyino, the heights situated between Dwaro-schna and the Inn of Lesch with his artillery.

Thus, it was believed that the front of the French position was covered by Schlapanitz and Bellowitz. Schlapanitz is about a mile and a half north of Kobelnitz, Bellowitz about 3 miles north of Kobelnitz. Furthermore, the French appeared to be shifting even more troops northward! Weyrother's 24 November strategic plan still held good. The Goldbach area was just another area to be marched over before getting to a potential battle zone, 'the plain, between Schiapanitz and the wood of Turas'. The Allies were not ignorant of the ground; on pg. 93 Duffy records 'the allies had an exact knowledge of the ground, for the Austrians had carried out large-scale maneuver on the same terrain in 1804.

Furthermore, by this time, they had accurately estimated the French numbers at about 60,000 men. On pg. 96 Duffy deals with the Weyrother's plan, which is in essence the same as the 24 November strategic plan;

In brief, Weyrother proposed a 'left-flanking' movement, by which the army would first pass the Goldbach valley on a wide frontage. Having gained the French right, or southern flank, the allies were to pivot on the area of Kobelnitz-Puntowitz and `throw and pursue'" the enemy northwards across the highway and into the wilds of the Moravian Switzerland.

In brief, Weyrother proposed a 'left-flanking' movement, by which the army would first pass the Goldbach valley on a wide frontage. Having gained the French right, or southern flank, the allies were to pivot on the area of Kobelnitz-Puntowitz and `throw and pursue'" the enemy northwards across the highway and into the wilds of the Moravian Switzerland.

All being well, the allies would be across the Goldbach on a frontage of more than four miles, 'and once the first column has detached four battalions to seize and hold the little wood of Turas, the remainder of the first column, together with the other three columns, will advance between this wood and Schlapanitz and crash into the right flank of the enemy. Three battalions of the fourth column will simultaneously gain the village of Schlapanitz.' The passage of the Goldbach was therefore considered as a mere preliminary to the decisive attack.

The rest of the army would lend support in a variety of ways. Lieutenant-General Johann Liechtenstein was to keep the bulk of the allied cavalry in a fifth column (5,375), and deploy in the neighbourhood of Blasowitz to hold the French cavalry in check, and cover the deployment of the infantry to the south with its horse artillery. To the right rear Grand Duke Constantine was to draw up the Russian Imperial Guard (10,530) behind Blasowitz and Krug, 'and act as a support to Prince Liechtenstein's cavalry and the left wing of Prince Bagration'. The Guard therefore constituted the only effective reserve-a notably small one for such a large army.

On the far right Bagration and the old advance guard of a nominal 13,700 troops were to remain on the defensive, guarding the baggage of the army, and covering the fork where the road to Austerlitz and Hungary branched away from the Brunn-Olmutz highway, 'but as soon as Prince Bagration observes the advance of our left wing, he must attack on his own account and throw back the extreme left wing of the enemy, which by then will be giving way. He must also strive to unite with the remaining columns of our army.

There are several points of interest here. The presumption is still that the enemy will run away - either on his own or because of the attack between Turas and Schlapanitz; so much so, in fact, that Bagration, guarding the baggage (!) will have to 'strive to unite with the remaining columns of our army'. It is no surprise that such a small reserve is kept. A battle needs a large reserve, but crossing the Goldbach on a front of 4 miles is not indicative of a deployment: in the presence of the enemy - it more closely resembles a strategic march along parallel routes to arrive at an assembly point. Furthermore, for those columns to align with each other, to deploy, then attack in concert, will require some time.

In fact, a look at the map shows the first three columns marching perhaps 5 or 6 miles just to reach the 'assembly area' where the attack coordination would take place. Some wargamers have wondered what to do with their 'Buxhowden' figure, since each of the three columns had it's own commander. Obviously he wasn't there to coordinate an attack on the Goldbach, but was instead to coordinate them upon arrival near the Turas wood. This would also explain why, after taking Tellnitz, he halted that column to wait for the others to come into line. If all the columns had to be aligned near the Turas wood anyway it might be just as easy to keep them aligned as much as possible during the march, even if some minor resistance was encountered along the way.

If we assume the columns could march at a rate of 2 miles per hour, we see that they were planning to march for at least 3 hours just to get to the assembly point. If we add an hour or two to prepare and launch the attack (which wouldn't be necessary since the French would be in panic-stricken flight already), we can assume that the Allies were figuring to use half a day before any battle would take place. Indeed, while the 4th column was to attack the extreme French flank, about a mile (!) south of Schlapanitz, the first three columns were to cross the Goldbach around Sokolnitz and Tellnitz.

That puts them between one and a half miles and two and a half miles south of where they thought the French furthest to the south were (resting on a point d'appui); and who, in any case would be occupied with the 4th column. If we consider the French right flank to be substantially near Schlapanitz and the Turas wood, where an attack, if still necessary was to be delivered, then we hive Buxhowden's columns outflanking the French at a distance, perhaps, of between three and four miles. it is understandable, though not excusable, that the Allied columns were less than careful about outposts or 1iason work. Their lack of attention to such details is another indication of the absence of concern about the French; after all they weren't near a battlefield, just some outlying French pickets or foragers! The resistance along the Goldbach was therefore puzzling, and unexpected. This attitude made the eventual French surprise attack even more of a shock, and that much more effective. Stutterheim reveals;

- The second column having arrived late on its point of formation, bad no out-posts in its front. During the whole night there was no chair of out-posts established in front of the position occupied by the combined army. . At one moment during the night, the enemy evacuated the village of Tellnitz in which out-posts were placed by a half squadron of Austrian light cavalry of the regiment of O'Reilly : but two hours after, the French returned in force, and posted a regiment of infantry in this village, from

the division of Legrand, forming a part of the right of Marshal Soult. The out-posts on the left of the allies sent, continually, patroles during the night, to their right, in order to establish a communication with the Russian advanced posts, but could never fall in with them.

Imagine the Grand Duke Constantine's surprise when, according to Stutterheim;

- From that time the centre and right of the allies became engaged in all quarters. The Grand Duke Constantine was destined with the corps of guards to form the Reserve of the right, and quitted the heights in front of Austerlitz, at tile appointed hour, to occupy those of Blasowitz and Krug. He was hardly arrived on this point before he found himself in first line, and engaged with the sharp shooters of Rivaud's division, and Prince Murat's light cavalry, commanded by General Kellermann.

The Austrian General points out that even after the French attacked, the Allies still didn't realize the situation, and had miscalculated where the French would be;

- immediately put III motion the massive columns which he had kept together, with a view of marching against the centre, and by that means cutting off the wint, which still imprudently continued to advance, for tile purpose of turning tile French army in a position which it did not occupy.

He shows Kutusov surprised and forced to assume the defensive, where the battle would be lost if he could not hold the Pratzen.

- General Koutousoff, whom this movement of the enemy had taken by surprize (thinking himself the assailant, and seeing himself attacked in the midst of his combinations and his movements), felt all the importance of maintaining the heights of Pratzen, against which the French were moving; they commanded every thing, and were the only security to the rear of the third column, which continued to advance and expose itself with the greatest imprudence, forgetting the enemy and every thing but the original disposition.

Note that Kutusov was not caught while attacking; rather he was 'attacked in the midst of his combinations and his movements' which were designed to bring him to a place from which he might attack. This would imply that an 'assailant' normally has the luxury of making combinations and movements, followed by attack, since defenders wn by holding the ground and beating off the attacker. It was Napoleon's ability to switch the roles without the Allies' consent that marked his strateqic talent here.

Stutterheim concludes with his explanation for the Allied fiasco;

- want of correctness in the information possessed by the allies, as to the enemy's army; to the bud plan of attack, supposing the enemy to have been entrenched in a position which he did not occupy; to tile move-ments executed the day before the attack, and in sight of tile enemy, in order to gain the right flank of the French; to the great interval between the columns when they quitted the heights of Pratzen; and to their want of communication with each other. To these causes may be attributed the first misfortunes of the Austro-Russian army. But, in spite of these capital errors, it would still have been possible to restore the fortune of the day, in favour of the allies, it' tile second and third columns had thought less of the primary disposition, and attended more to the enemy, who, by the bold, ness of his maneuver, completely overthrew the basis on which the plan of attack was founded.

It is interesting that the typical wargaming assumptions of better firepower, morale, training, national differences, or having the Allies off the Pratzen height advantage instead of on it, aren't mentioned here. In fact, he even states the situation could have been restored if two columns 'had attended more to the enemy' - in other words, they weren't ready for a battle and were unable to react properly when they found themselves in the midst of one!

He might put it by saying that the Allies started a march around 6:30 in the morning with the expectation of fighting a battle (if one became necessary) as attackers against French defenders at noon on a battlefield about 3 miles away from the Pratzen, Napoleon, meanwhile, was expecting to be the attacker in a morning battle against marching Allied columns south of the Pratzen who would be forced to turn and defend themselves from annihilation. The actual event saw a French ambush of the Allies in the middle of a march maneuver. However, the key to the battlefield unexpectedly became the Pratzen when Allied slowness caused it to still be occupied when the French arrived, and with the unexpected presence of Bagration, yet still the French surprise attack forced the Allies immediately to the defensive, having to hold the Pratzen, which they were unable to do. Therefore, Austerlitz was not a typical wargamer's mutual attack battle, but was instead a typical Napoleonic example of a battle with an attacker and a defender.

How would a wargame set-up reflect these conditions? The French player would be the attacker, the Allied player the defender. Allied columns would be spread out in their marching formations in the locations they occupied when St. Hilaire and Vandamme collided with the Allied 4th column, at which point the game would begin. The French would have to attack and rout the Allies while Kutusov would try to hold the Pratzen and get orders out to his out-lying columns tu forget the original plan. Good Luck!

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 1 No. 84

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1985 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com